Alessandro Truffa

January 2025

The thirteenth edition of the Premio Francesco Fabbri per le Arti Contemporanee saw this year’s winner of the Contemporary Photography section, the young Turinese photographer Alessandro Truffa.

We met with him to explore the themes of his photographic research as a way of understanding and investigating real-life phenomena such as the climate crisis, popular beliefs and the relationship between man and the environment.

The winning work for the contemporary photography section, Bee in a Test Tube, is a photographic light box and part of the larger 432 Hz research project. In this project you interweave documentary photography and pseudo-scientific storytelling to question human prejudices that arise when studying the behaviour of other living creatures, in this case bees. The project creates a space of interspecies coexistence that moves between fiction and scientific fact. How did this project come about? What did you want to show?

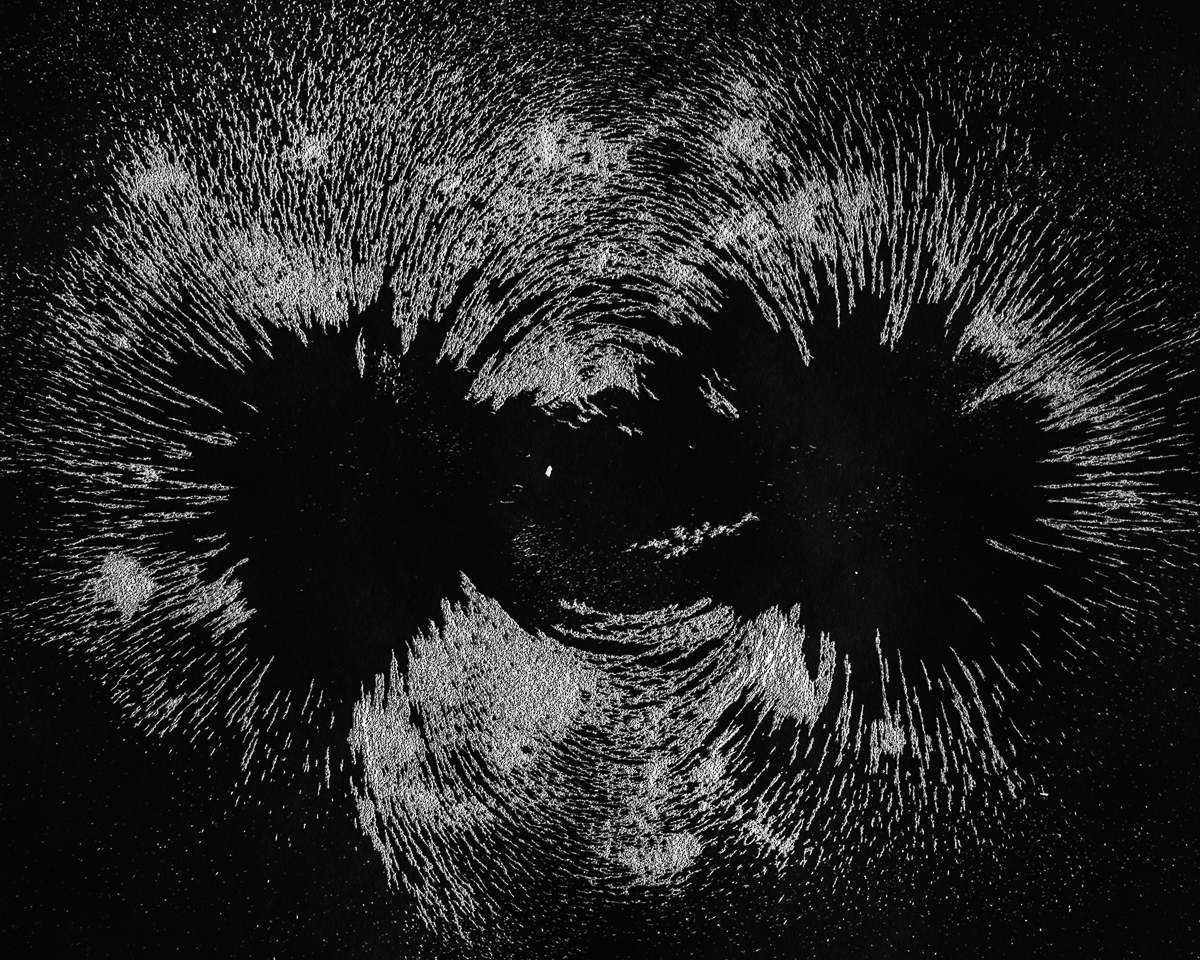

Bee in a test tube can be defined as a kind of synesthesia, since it is an attempt to visualise a sound by translating the song of a queen bee into light impulses.

The 432 Hz project, which is currently underway, came about at a time when I was starting to research the relationship between humans and pollinators, because I was interested in exploring how humans relate to the subject of animal intelligence, and the prejudices related. At the time, I was taking photographs inside a university research laboratory studying pollinators and, in particular, the effects of pesticides on their motor skills and fertility. To explain what interests me, I always start with a quote from Marx, challenged by Timothy Morton in ‘Dark Ecology’: “The best bee is always worse than the worst architect”. This idea somehow presupposes a positioning bias of the human over the animal, because whereas a bee would merely execute a mere algorithm, like an automaton without a conscience, the architect would always be a conscious author of his work. There are therefore unconscious dynamics that condition us in our relationship with other life forms – such as the idea that small brains are incapable of complex tasks – and in this sense create gaps and blind spots in our way of translating and interpreting language and animal behaviour. In the text ‘In the Mint of a Bee’, Lars Chittka cites various experiments that attempt to deconstruct these mechanisms, such as that of Charles Henry Turner, an entomologist who lived in the second half of the 19th century, who was the first to empirically demonstrate that bees construct their nest location using spatial reference points. After noticing that a solitary bee had built its nest next to a Coca-Cola cap left on the street, he moved the cap next to a specially constructed artificial nest and watched as the bee entered its new nest without hesitation. He thus succeeded in demonstrating that the bee had a memory for landmarks rather than instinct.

The 432 Hz project consists of documentation photographs interwoven with images depicting fictitious scientific experiments that seek to challenge our certainties about what we know on animals, to ask questions rather than assert theses. The work therefore explores, through photography, the role that an image can play in moving from being an evidential and scientific tool to one capable of constructing imaginative truths.

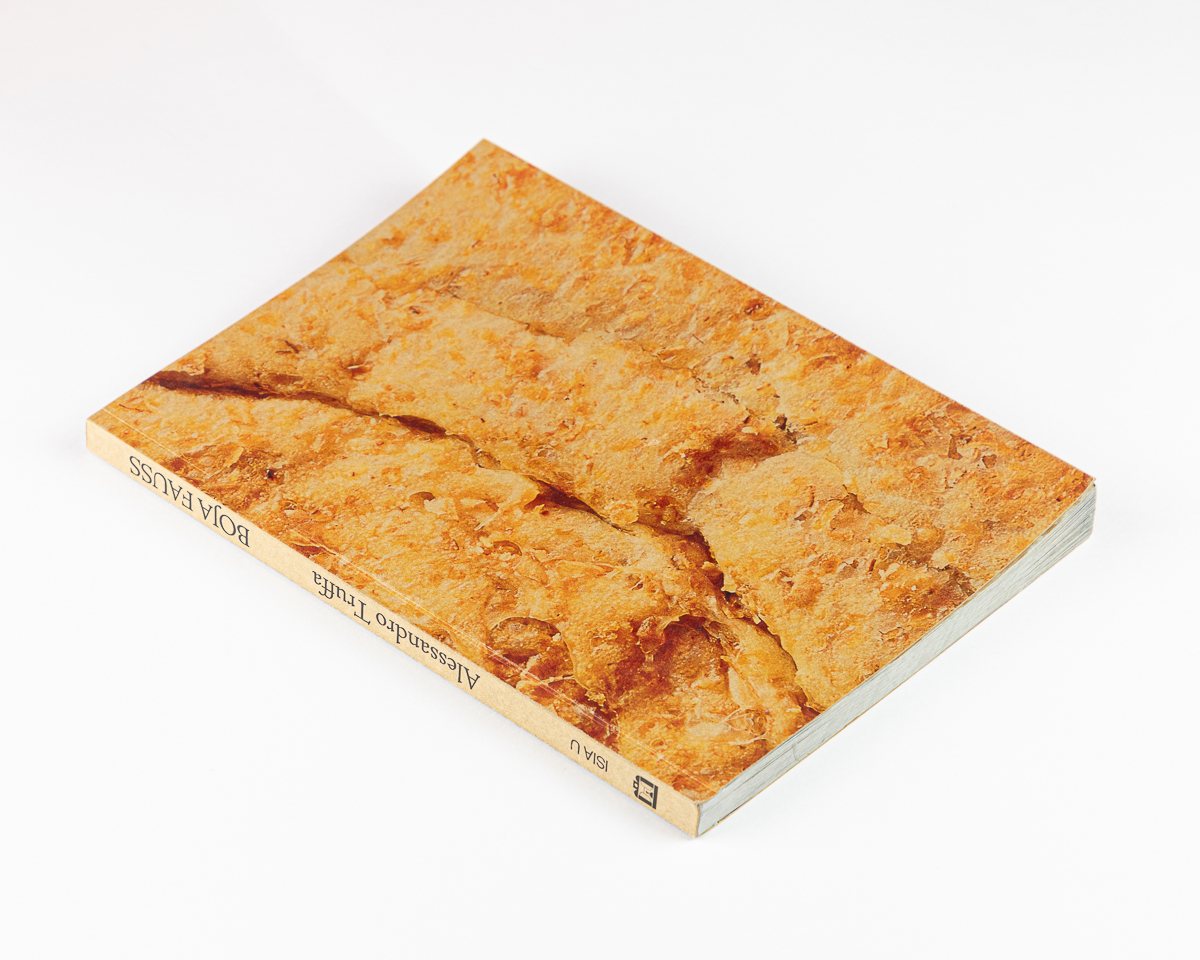

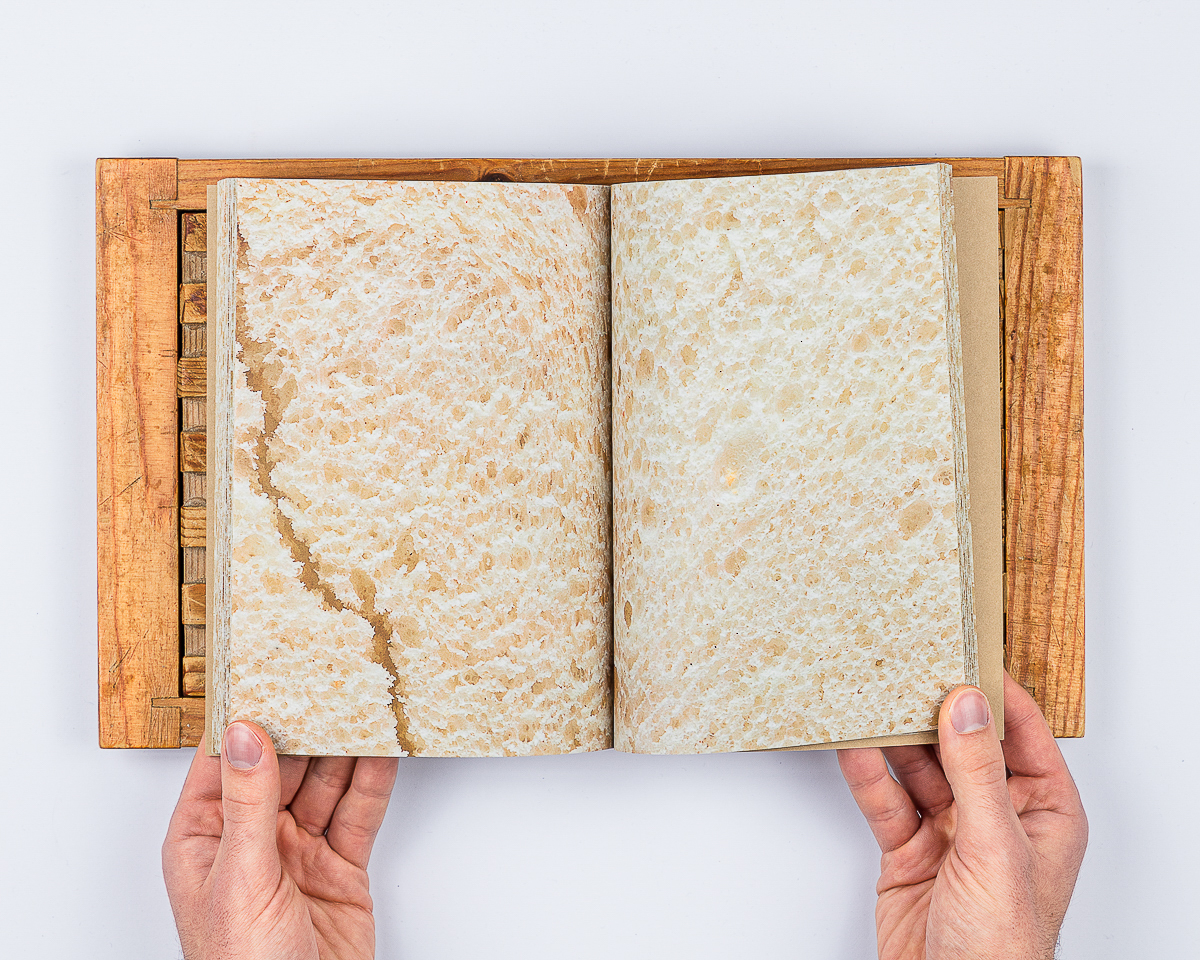

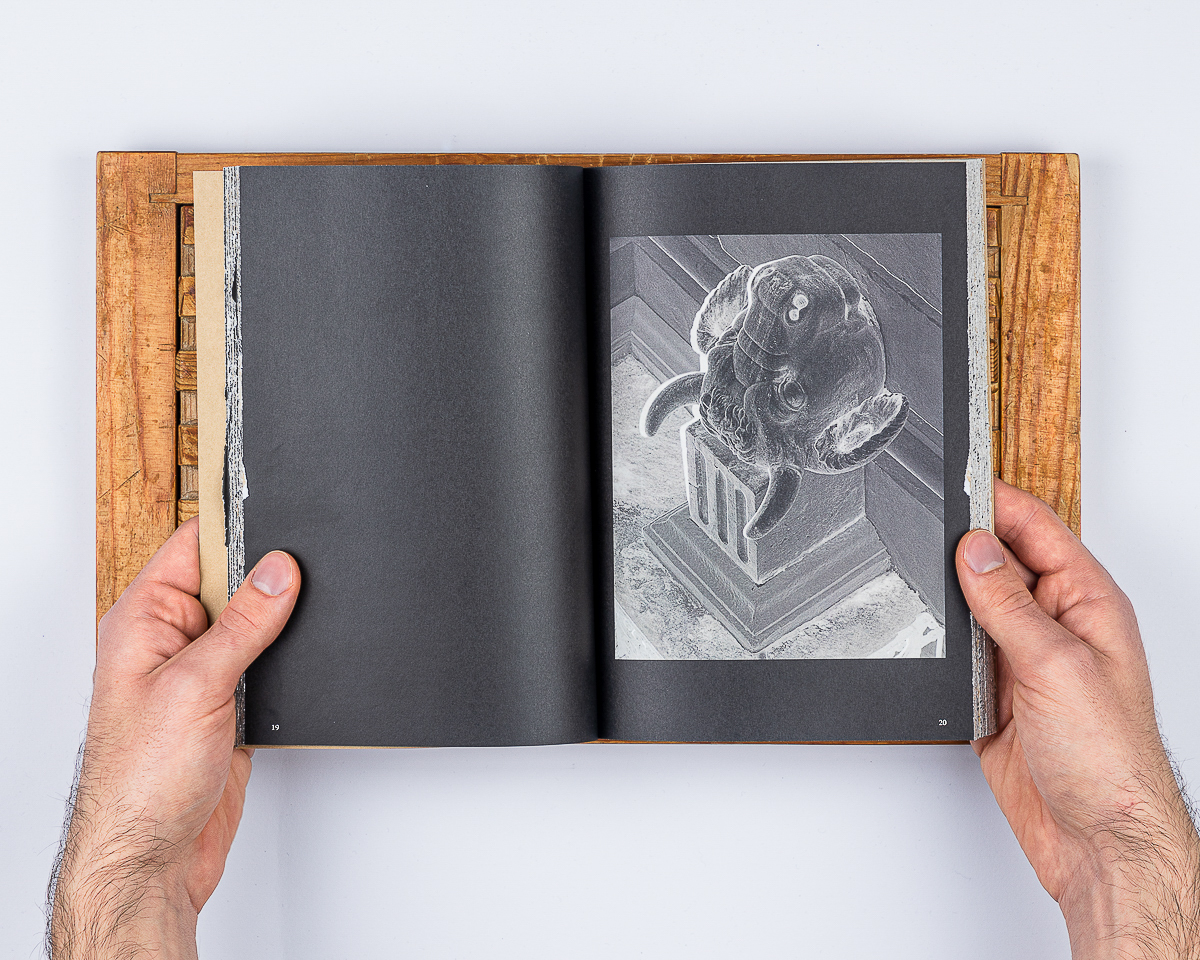

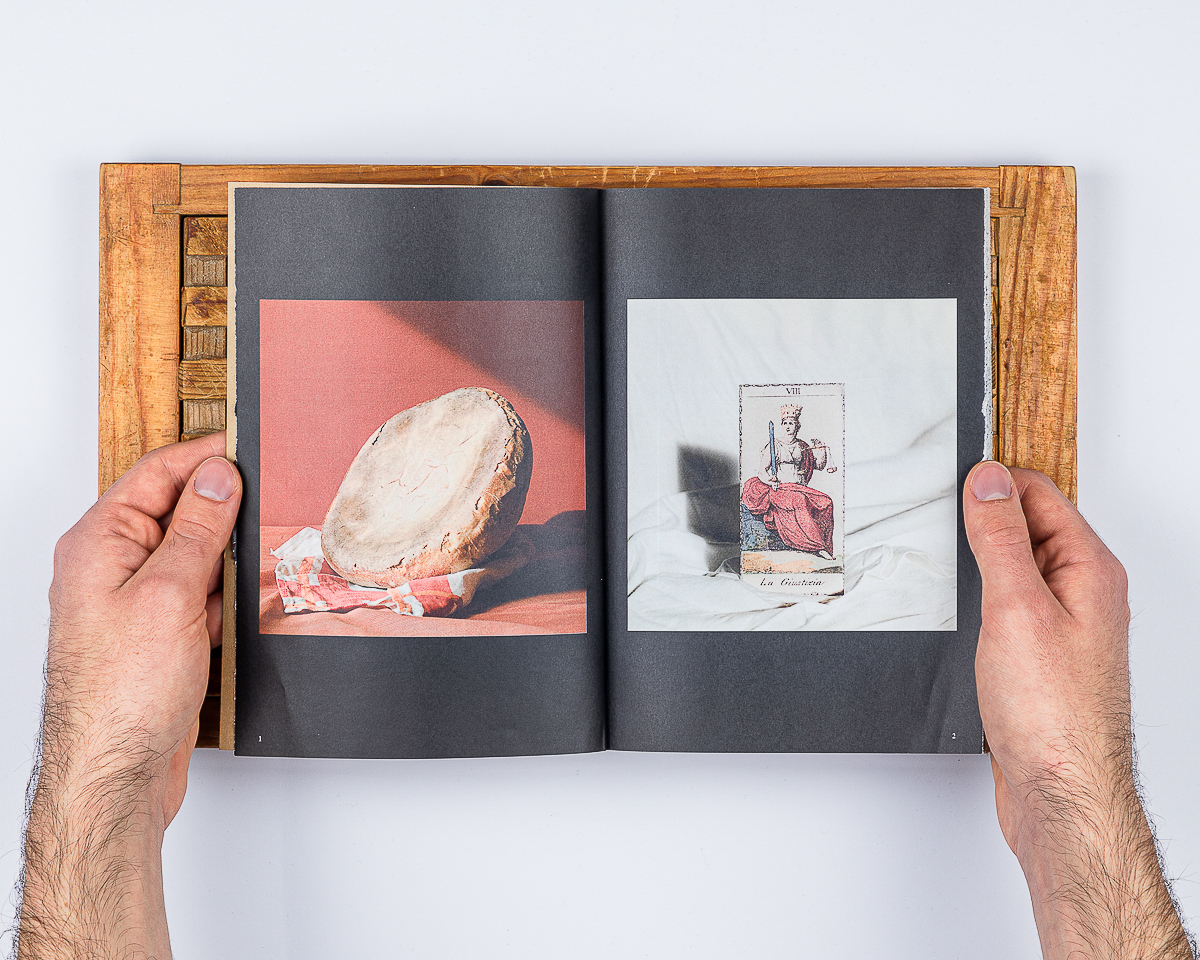

Another recent project, Boja Fauss, is inspired by a historical event: the last application of the death penalty in Italy, in Turin in 1947. This fact is linked to the local legend that, when an executioner bought bread, it was handed to him upside down as a sign of contempt; the remonstrations of the executioners and the subsequent decree forbidding this practice gave rise to the pan carré, a square loaf in which it was impossible to distinguish the top from the bottom. This made it possible to continue to mock the executioners by handing them the bread upside down. In your project, the pan carré is reinterpreted as an instrument of dissent against a figure seen as the embodiment of the control exercised by power. Boja Fauss is a project at the intersection of oral history and official history, how does this emerge from the images? The book, which is in the form of the pan carré, what images does it contain?

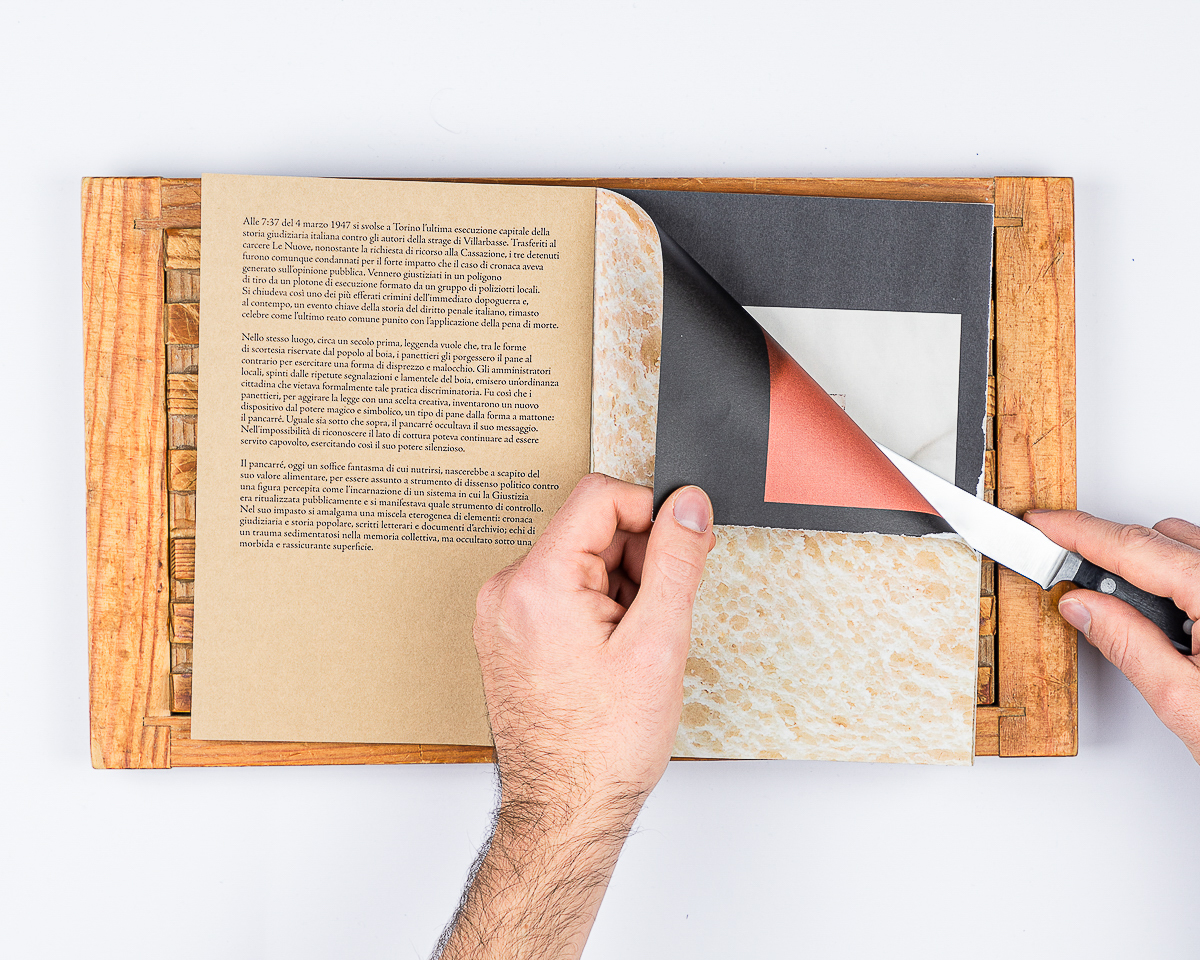

The structure of the publication and the decision to keep the book’s pages intact were functional in order to hide the images within the pages, in order to recreate, in a playful way, that dimension of esotericism that was also the basis of the original legend.

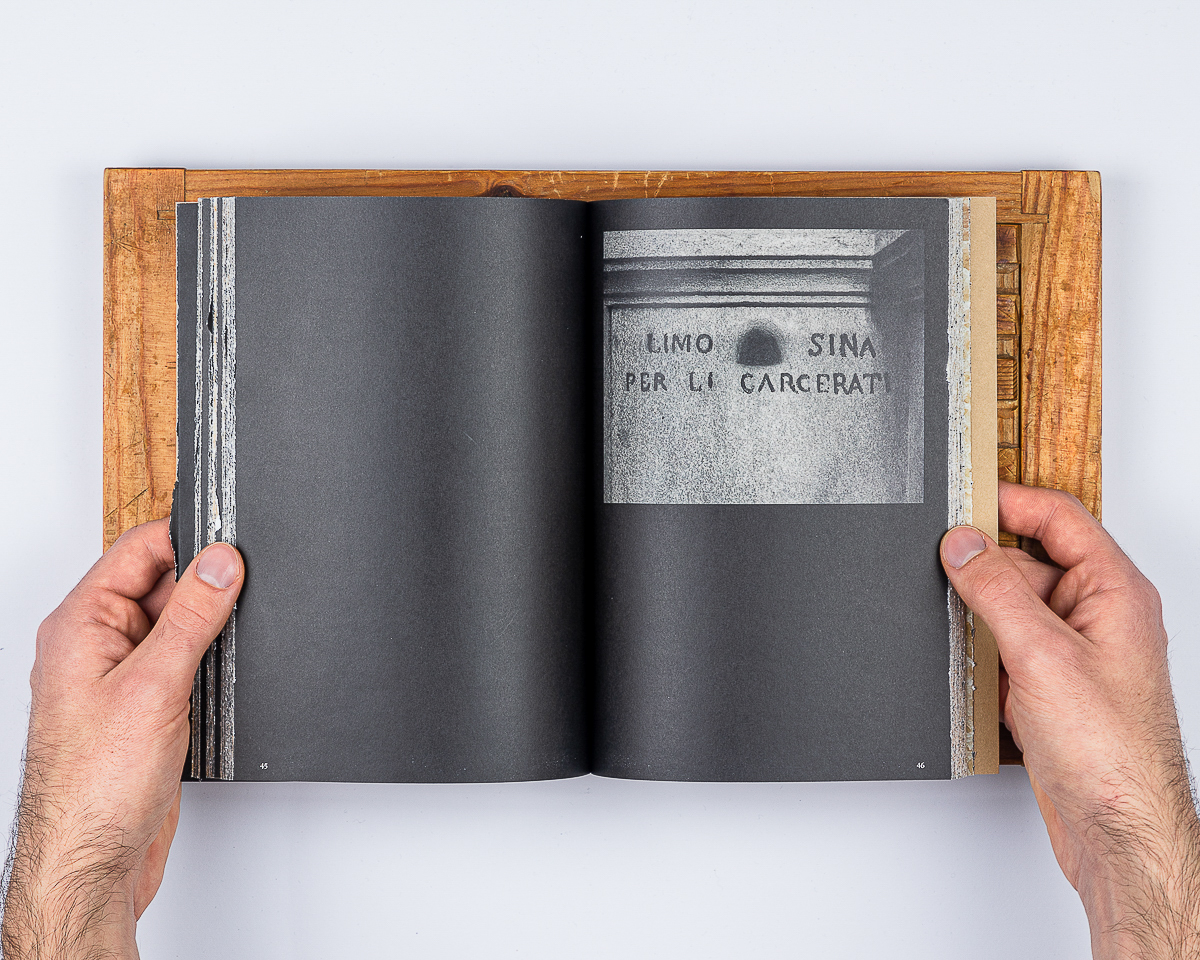

Within the project there are different types of images that work on the stratification produced around this theme, orienting the research not so much towards a specific direction, but towards the contamination of different approaches and methodologies. I was very interested in working on the dialogue between official history and popular history, that is, between a more institutional approach and a more exploratory one, linked to the proposals that have been created around this theme. Part of the research was therefore based on the study of various archival materials relating to the chronicle and official history, such as court documents and news photographs published in newspapers. These materials were researched and photographed in various institutions in Turin, such as the Historical Archives and the State Archives. I also photographed in historical places such as the Church of the Misericordia or in places of remembrance such as the Cesare Lombroso Museum of Criminal Anthropology and the Museum of Le Nuove Prigioni. These images create an archaeological path in the dark memory of these historical events, which serves to trace concrete coordinates within the work.

Alongside these historical materials, I have placed images that are more suggestive, such as a series of square blocks of bread that I cooked and photographed as if they were stones, to refer to the semantic use of bread, which is obviously deeply intertwined with Christian culture. Other images, on the other hand, start from some linguistic and etymological suggestions, such as the cockroach. In fact, in the Piedmontese dialect, the word ‘executioner’ (often distorted into ‘baboia’) has a double meaning: on the one hand, that of the ‘executor of justice’ and, on the other, that of the ‘cockroach’. Similarly, chains allude to the Greek etymology of the word. The Greek word ‘boeiai’ referred to strips of cowhide, from which the Latin word ‘boia’ (Italian for executioner) was derived, which was used both to mean ‘lace’, ‘chain’, ‘instrument of torture’ and to denote ‘the executor of justice’.

There are also images based on allusions to magic, such as the raven, which is not only one of my favourite animals, but also a symbol of the first stage in the alchemical process: the nigredo, the moment when all the ingredients must be ‘macerated’ into a single, uniform black mass. For the same reason, in the book, the different types of material are not separated, but fused into a single narrative, creating connections and links between different fields of knowledge.

With your practice you question the use of photography as a cognitive tool of the real, you challenge the boundaries between the imaginary and the concrete, and you try to slip through the gaps in the processes of knowledge construction. Photography is contaminated by other disciplines such as the natural sciences, semiotics and anthropology, and the photograph of the document becomes a narrative element. Could you tell me more about how this applies to your projects?

In my projects I always try to work on the layering and contamination of different approaches, I like to use photography as a tool of investigation, without using it as a handmaiden for a specific discipline, but rather as an autonomous language capable of inserting itself into certain processes and elaborating its own results. At the same time, I do not consider the single photographic image as the final goal of my work, I hardly work on the series, but rather on the construction of projects that always use different languages and materials related to different fields of knowledge, because I am convinced that knowledge always comes from the plurality of approaches and visions. By investigating a theme and developing a research project, I try to put my gaze and the images I produce in dialogue with pre-existing archive material or material produced by the subjects I relate to.

One of the first works in which I experimented with this design methodology was Fuoco contro fuoco (Fire against fire), which arose from my personal fascination with an alternative medicine practice for healing St Anthony’s fire, which I discovered was practised by a healer in my home town. What I wanted to reflect on through this work, apart from the ritual and its homeopathic nature, were the gaps that inevitably occur in any process of knowledge transmission. For this reason, part of the work was based on the creation of a visual short-circuit of images belonging to different fields, such as science, nature and religion, in whose indistinct whole the origin of the ritual itself is hidden. Finally, some images were produced directly by the healer, who marked the photographic paper with printing chemicals as if it were skin. It was a very interesting experiment to have the healer mark the photographic paper, because in this way she was able to explain to me that each mark she made corresponded to a specific type of skin manifestation of the disease, not by chance several anthropologists have called these figures ‘sign women’. These last images alternate with an interview, a dialogue between the healer and myself, which allowed me to include materials in the work that were not exclusively produced by my gaze, and to make them interact directly with her personal account of her practice.

For me, photography exists in a paradox: while it is socially seen as a form of testimony, it can also be a lying tool with which to construct alternative truths. I am interested in this duality because of the possibilities it offers to go beyond what we accept as ‘real’ and work in the realm of the ‘possible’. In 432 Hz, for example, this emerges from the combination of scientific documentation produced in research laboratories, images produced by empirical observation of pollinating insects and the creation of fictional experiments.

In Boja Fauss, on the other hand, chronicle and legend are intertwined in a narrative in which the legend provides elements for a deeper understanding of the trauma that official history has produced in popular culture.

This way of working with multiple layers reflects my idea of photography as an ideal tool to create complexity and to let my vision of reality interact with different materials, building relationships and dialogues.

What are you currently working on?

As well as working on the 432 Hz project, I am currently preparing for an artistic residency in Dalby Forest in England in April. This is a very nice opportunity that I received as a reward for my participation as a finalist in the exhibition of young Italian photography, for the Luigi Ghirri Prize, during the European Photography Festival in 2024. The project, supported by Photoworks and the Italian Cultural Institute in London, will give me the opportunity to spend about ten days in Dalby researching ecological and environmental practices, participating in visits and meetings with national and local arts organisations, and giving back the experience at an event at the IIC in London.

It will definitely be interesting for my growth and development of new themes.

PHOTO CREDITS

Alessandro Truffa, 432 Hz, 2023, lightbox and photographic series

Alessandro Truffa, Boja Fauss, 2023, book

Alessandro Truffa, Nioko Bokk, 2023, installation view at Contaminazioni – Giovane Fotografia Italiana #11 – Premio Luigi Ghirri, Palazzo dei Musei (Reggio Emilia), ph. credit: Bruno Cattani.