Interviews from the ‘PRESENT IS THE NEW FUTURE’ open call

In your artistic practice, you investigate the material and specific history of places, as in Che sia Prospero!, 2024, or Kick Me, 2019. In the first case, you unearth the popular legend of Prospero Baschieri, a peasant from the Bologna plains who lived at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, and who ended up embodying revolutionary ideals against the French occupiers, leading a popular movement long before the Risorgimento uprisings. In this work, you reconstruct her face with grass and hay from an 1810 sketch and display it during a performance, just as his severed head was displayed in the main square after his capture. In Kick Me, on the other hand, you reproduce on tarpaulins five bunkers on the coast of Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, your home town. The tarpaulins delimit an enclosed area containing footballs made of tiles that have been illegally dumped in the open air. In these two projects, but also in your research in general, you attempt to re-signify the present, to re-read historical events in order to shed new light on the present. Is this your way of approaching contemporary issues – what can the figure of Prospero Baschieri tell us, or a reinterpretation of the violently man-made landscape?

Kick me, like my previous projects, poses the macro question of what ‘home’ is, a question that recedes and then returns with a vengeance, a kaleidoscope that constantly refracts different flashes. Specifically, he looks at what has been, with a focus on southern Italy, where there are many unfinished houses, ready to house children who will never inhabit them. Was there an excess of love? Of belonging? Of selfishness? Of trust? What is the fault of a father or mother who wants to see their child grow up? Perhaps they were deluded by the economic boom, certainly they did not foresee the network and the resulting desire to want what they did not know they wanted, and the illusion that they could do anything. I would like to believe that the compulsion to build was a misguided act of love and the abandonment a sad failure.

Che sia Prospero!, my latest project, starts from the first little information I received about Prospero Baschieri during my last residency. I had been asked to create a project about the area, so I read, in chronological order, about the Bassa Bolognese since its origins, a quiet area that has always been devoted to agriculture. The leader of the banditry stood out between the lines, was described in brief and was little known to the locals. Thanks to the work of the team that assisted me, we found historical documents that outlined a double profile: one of a man who was ruthless and ruinous to everyone, the other of a hero of the destitute. But no one denies that he was a fugitive, that he was always close to home but could not live in freedom, that Prospero was a stranger at home and that, although he fought for the rights of all, he died a martyr and a laughing stock at home. Yesterday he was a peasant, today he has a political, religious and sexual orientation, a voice out of the chorus that raises a flag among the masses. Prospero then takes a leap into history and walks among us, he is one of us. But Prospero did have one small victory: we took the sculpture to the back of Granarolo’s townhall for the town’s most important festival, where we had to present it to everyone and tell its story. Unknown to me, and to my great surprise, the word ‘robber’ was everywhere: themed menus, people dressed in period costume, leaflets printed by the town council telling his story, a street sign with a detailed view and the promise of a history festival for schools and citizens around Prospero. Here you understand that the work is a remnant, it is now in people’s mouths and hearts, it is contemporary. In short, these are fruitful actions, always.

In other works you experiment with the relationships between objects, people and the stories that weave them together, and their relationship to the past and present.

The past, especially the recent past, helps me to understand the present better. It sounds like a cliché, but I always manage to surprise myself. There is no nostalgia or worship, I consider researching the past as a ‘litmus test’, dynamics that we consider outdated are very often current, others that I know superficially turn out to be extremely interesting after a closer reading. So often we hear people say ‘it was better before’, without giving reasons, and I wonder if we are so sure, because I would like to understand whether we regret being born in 1991 (in vain) or ride the wave.

In some projects, you explore the placement of works in environments that are not explicitly dedicated to art, as in Where Where Where, 2021-2022, a series of two exhibitions realised in a volcanic crater and in a megalithic complex; in OSANNA(!), 2021, which, although in the context of spazioSerra, is a kiosk inside a metro station; and also Panacea, 2023, which is exhibited in a historical pharmacy. These are certainly projects born in situ, but I would like to ask you how, and if, the development of a project changes when you work in these contexts? What are you interested in trying out?

Site-specific projects always excite me, as in the case of Che sia Prospero!. The site is clearly the key to interpreting the intervention, not as a mere container, but as an element of construction. In the projects you mentioned, the works and the space were mutually dependent, and the work was generated in parallel.

Where Where Where began as a strong need for confrontation between site, artist, curator/critic, work and public. It was in the middle of the Covid period, I was longing for authenticity, often bored by the public in big cities, I wondered how much was real and spontaneous in the exhibition package and this project was a test. How does a work in the crater of a volcano compare? Does it hold up? How does the writing (which in this case was not meant to describe the work, but to be a work in itself) relate? What kind of audience is willing to climb a volcano to see an exhibition? In a gallery it is easy.

We were there, with our backpacks, dirty, sweaty, but with our hearts in our throats, ready to engage in a discussion with the public, a public that had clearly never arrived, on the island of the same name, as well as in a more accessible place like the Argimusco plateau. It was true, the works breathed like the place, we breathed heavily.

For spazioSerra, the situation was different from that of a gallery, the time was the same, the public was passing through and in a hurry, the work was changing, showing itself always different, the construction of the design was imposed by the intersection of lines starting from the structural elements of the aedicule, the colours were those present in the signs (white and blue). It was observed from the outside and in front of everyone’s eyes, the work phagocytised itself, it was a stumbling block, in its slow mutation it underlined a time limit to observe it in its integrity, the demiurge artist was shunned by an autonomous work. I was testing failure, the audience and how much sense it made to build or destroy in a space of the unemployed. The cleaning lady (a woman, all of a piece) confessed to me that at the end of each shift she went straight to see what had happened and was desperate to catch the mechanical device that was messing everything up.

For Panacea I immediately set my sights on the goal, I needed an exhibition that would put my years in Milan in order and it had to start with an historic pharmacy in Sicily, a pharmacy that kept ancient recipes for curing illnesses with what the surrounding landscape offered, landscape and cure were key elements of this project. It was not easy because there are few old pharmacies left intact and none of them have exhibitions, so I was bounced from the first (which was closer to home) and the second, after a period of getting to know each other, a wonderful collaboration was born. I had access to the archive and everything I had already found in the oral tradition was in the recipe book. The point is that many of these substances did not cure at all, but relieved discomfort, probably also psychological relief. I have the same feeling when I come from Milan to Sicily and go for a walk on the outskirts of the city, the sights and smells give me a certain relief that I cannot explain, an immediate calm.

So the exhibition was an explosion of smells that immediately evoked memories and landscapes, a panacea. I made 13 reproductions of my right leg from a plaster cast, 13 like the years I spent in Milan, legs that have crossed Italy, carrying with them the fractures of the journey, marks that make each piece unique, that characterise it. The floor of the pharmacy was covered with 13 dried aromatic herbs and the fractures of the sculptures were filled with powders of the same mixed with putty. Assumption and reality merge, as do body and spirit, the physical journey and that of the mind. The exhibition, in its first public presentation, could not have manifested itself elsewhere.

What topics have interested you most recently? And what are you currently working on?

For some time now I have been rearranging my thoughts, in power I am interested in everything. The topic of ‘home’ has widened over the years and at the moment the focus is on a feeling rather than a specific subject. The feeling is that of never feeling quite at home, that feeling of longing and frustration typical of generations close to mine. When I ask friends and acquaintances where they see themselves in 15 years, most of them have no idea (myself included), as if we are waiting for something but don’t know where, when or if it will ever come. I am investigating this question by re-reading texts on mass tourism, I find there is an assonance between the figure of the tourist (who follows predetermined routes and destinations) and the design of one’s life according to the models we aspire to, I wonder how much is induced and how much is intrinsic necessity. I have found parallels with a plant widespread in Italy that needs trauma to multiply, and I am studying its properties and uses. These are some of the elements I’ve been working on for some time, adding pieces when I feel it’s appropriate, I’m imagining a large environment where the public can immerse themselves, I want to take my time, I don’t have a deadline at the moment, I’m well on my way.

Going back to what I said earlier (a general a priori interest), I believe in and try to approach my projects with a method, this is typical and in its mutation it always takes into account certain pivotal points that I still hold on to. I am more interested in the ‘how’ than the ‘what’.

PHOTO CREDITS

Che sia Prospero!, performance and installation, 2024

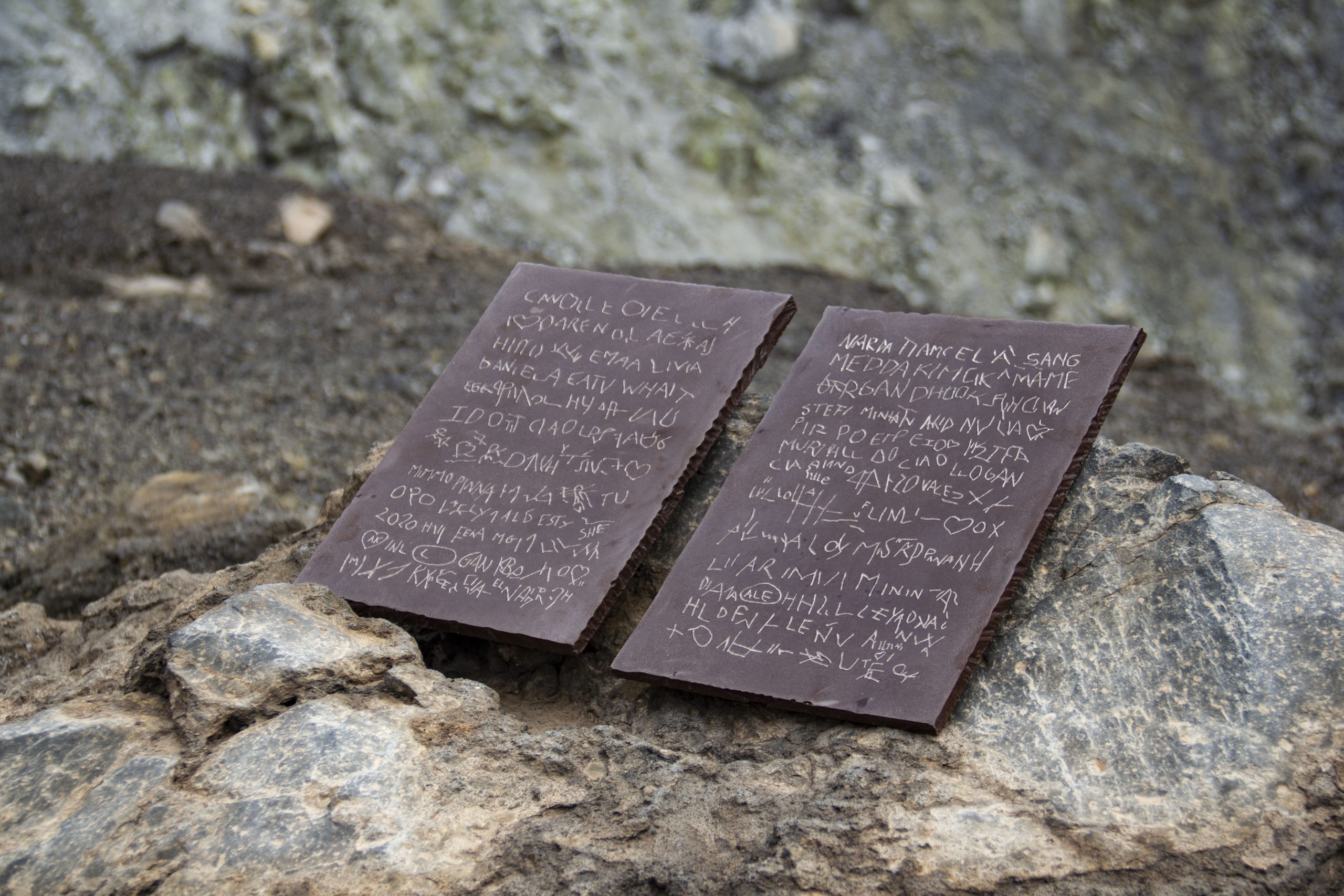

WHERE WHERE WHERE, engraving on volcanic sand and resin tablet, 2021

Kick me, reclaimed tiles, cement mortar, steel, synthetic lawn, wheatgrass, print on nautical fabric, 2019/2022, Courtesy Spazio A21

Detail of Kick me, reclaimed tiles, cement mortar, steel, synthetic lawn, wheatgrass, print on nautical fabric, 2019/2022, Courtesy Spazio A21

Panacea, installation view, Courtesy Museo dell’Antica Farmacia Cartia, 2023