Alex Majoli

Referring to a brief interview you gave a few years ago, where you spoke about the relationship between reality and ambiguity in photography, could you elaborate on these two concepts and their connection, especially considering the widely debated photos taken by some reporters (probably) present during the attacks on October 7th, 2023, in the Israeli territories?

The issue can be very simple or intensely intricate. Please excuse the post-Walter Benjamin lecture, but let’s start with the simple fact that photography derives from the raw and rigid technology of the camera, which is objectively designed to capture real things, real people, and objects that have truly existed—a photocopier of life. Then, there’s the photographic language inherited from other images like paintings or drawings, which over time took on the role of depicting human life, trying to escape the mere concept of “real photography.” In my opinion, by playing within the prison of “capturing real things,” the ambiguity that a photograph can contain transports the image into another sphere of human receptivity. Following Umberto Eco’s lead, this ambiguity becomes an open work: whoever sees that image also becomes its author. A photograph devoid of ambiguity is certainly useful, but deeply rooted in the vast chaos of labeling and archiving. In my exhibitions and books, I try to remove captions as much as possible, but that’s a long story.

As for the photographers present on October 7th, this is not a new phenomenon in the history of photography. Just think of many images from the Vietnam War or other wars and conflicts—whether photographers were present to witness an event or not. What’s unusual about living and photographing as a journalist in the eternal Israeli-Palestinian conflict, being daily present in the streets of the small Gaza Strip, and realizing that something unusual is happening that day? When I used to cover the news in Brazil with local newspapers, we had a radio connected to the police’s, and sometimes we arrived before them. What’s the perception that makes Eddie Adams’ photo of the executed Vietnamese soldier acceptable, while a Palestinian photographer documenting an event nearby his home in Gaza becomes a suspect? Michelangelo certainly wasn’t a priest while he was imagining the face of God. War is horrible and brutal—haven’t we understood that yet?

Sticking to the topic of reality, Jean-François Leroy, director of the Visa Pour L’image festival, said that people still want to see the real world, the true one. What is your opinion on this statement, and what are your thoughts on constructing an image with the aid of AI?

The problem lies in that concept of perception: what is it? What is the real world? I find it simplistic to say, “this photo is real, that one is not.” Going back to the discussion of captions, those, when present, must be “objectively real,” but in my opinion, the image can be anything. It goes without saying that I expect seriousness from those informing me about an event or fact, so AI cannot be considered just because, as of today, AI doesn’t leave the house and go see what’s happening. At the same time, when I look at Picasso’s Guernica, I understand the tragedy of war, and it makes me reflect. However, I don’t expect Picasso to be considered a war correspondent, but his image prompts reflections that are on par with a “real” photo taken in an armed conflict. We must strive to imagine an agora where everyone brings their experiments, each with their own ethics, but all valid for dialogue.

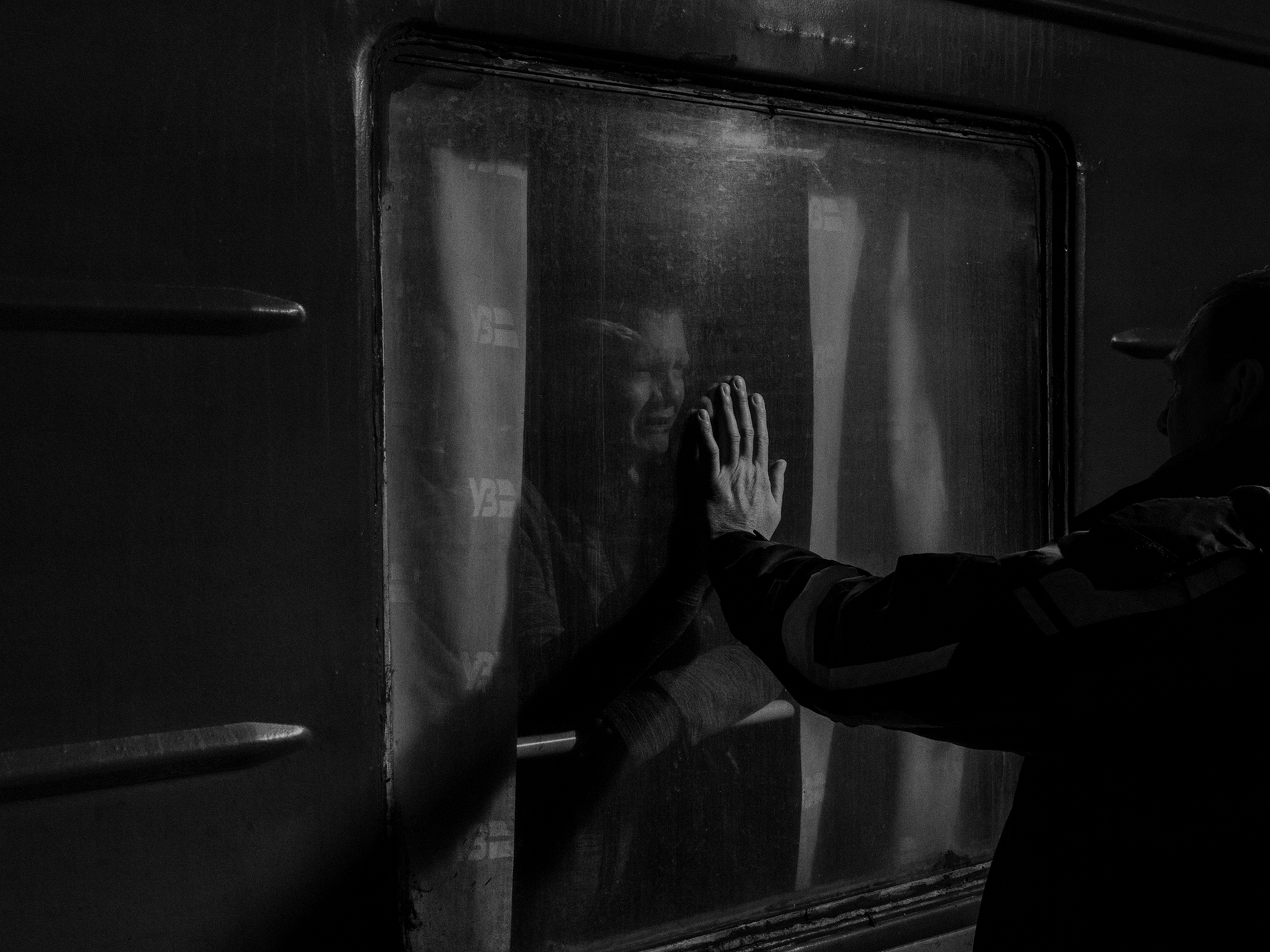

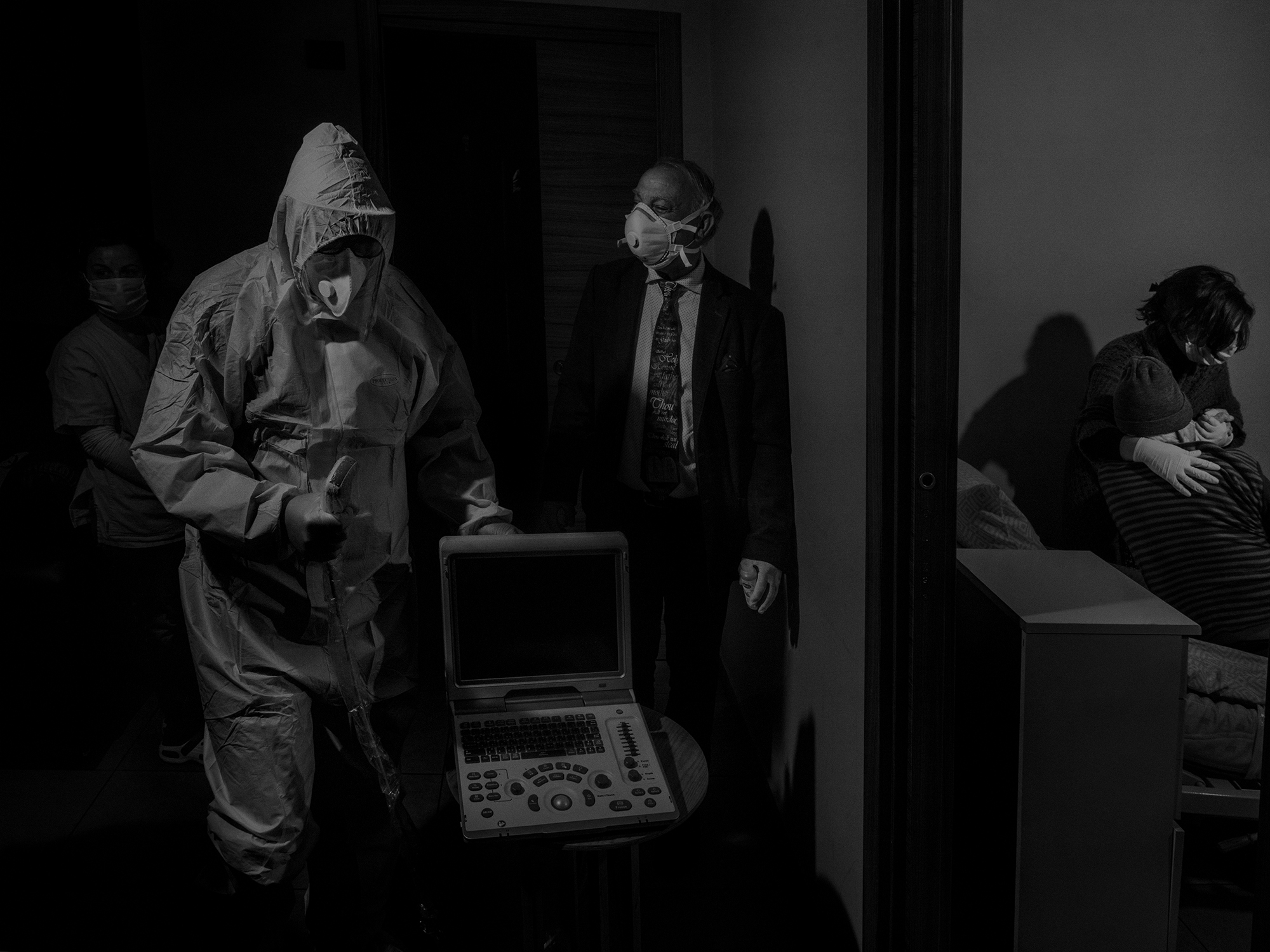

Looking at your photographs, we notice that the subjects always seem to emerge from darkness or obscurity. We would love to know what led you to this specific poetic choice and what ideas drive you to work this way.

The aesthetic I chose for this long-term body of work called SCENE is more of a burden than a poetic. For almost 20 years, I’ve been trying to explore/experiment with the (Pirandellian) concept of us “human beings” acting out our roles in society. At first, I tried to capture the “masks” in society isolated in the dark, but after a series of small “conceptual failures,” I needed to add the “studium,” which for me is the scenography of our society. That’s why in 2008, I had the intuition to bring a “skenè” into the real life of human beings. The “performance” of me building this skenè around people living their lives or societal events makes everything and everyone suddenly become the protagonists of an unwritten play, their own play. In my opinion, this skenè/stage transforms what is already real into something “more real,” freezing the improvisation of our acting in society and, in many cases, amplifying it.

We know you were among the “founders” of Cesura, an innovative project and a new form of collaboration between professionals. In your opinion, how should a young person approach photography professionally, considering how the publishing world has changed today?

Cesura Lab was and still is my studio that I wanted to create in the hills of Piacenza, when I moved to New York to experiment with my photography. Over the years, a series of young people who wanted to assist me passed through, and at a certain point, I convinced them to create their own collective in those hills rather than follow individual paths toward that “hamster wheel” society forces us to chase. Today, Cesura is both a collective and a workshop where one can learn about photography. A young person should turn off their phone and engage with themselves rather than conform to society’s appearances, trying to build questions that can lead to their own photographic alphabet—a sort of transparency of the self. Professionalism has nothing to do with the market but with building that alphabet. If you can’t form it, it means you’ll have to enter the bazaar of those offering the same goods at a lower price than the stall next door.

Just as you had to modify your way of working—if you had to modify it—is there still a possibility for photojournalists in the publishing industry?

Indeed, I didn’t have to, I wanted to, but it’s simply a perpetual evolution of being a professional who dedicates tons of hours to a single obsession. The issue and problem for the photojournalist lie in the word itself: if there are no more newspapers, or if newspapers have primarily become containers for public opinions or press releases, it’s clear that those who used to create those photographs are now losing their jobs. So, the question is: do we really no longer need news and an understanding of our society? Then, of course, we have to shout “wolf” when AI comes along. We’re no longer able to create communities and are left alone with our phone friends… who even take pictures now, and we read opinions formed on other opinions… it’s madness.

Does it still make sense to teach photography today?

It makes sense to talk about images and understand why we make them, forgetting about how we make them.

The interview was conducted in early 2024