Features #28 - February 2024

Andrea Bellini and Nora N. Khan

NICOLAS VAMVOUKLIS IN CONVERSATION WITH ANDREA BELLINI AND NORA N. KHAN

Embarking on the scenic train journey to Geneva is always a captivating preamble to an immersive experience in the world of creativity. As the charming Swiss landscapes unfold along the way, anticipation builds for the latest installment of artistic innovation: the 18th Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement. The exhibition, titled “A Cosmic Movie Camera” showcases fifteen new productions specially developed for this occasion, capturing the essence of experimental media.

Among the noteworthy projects, Lauren Lee McCarthy’s imagined “Saliva Retreat” stands out — an intimate lounge space inviting discourse on bodily exchange, autonomy, and data privacy. Emmanuel Van der Auwera contributes a hypnotic video-sculpture, employing generative artificial intelligence models and neural radiance fields to mesmerize visitors.

Diego Marcon’s film “La Gola” skillfully navigates melodrama, juxtaposing the delicacies of a dinner with the progression of worsening symptoms. Not to be overlooked is Formafantasma’s multimedia installation, delving into the recycling of electronic waste. Their investigation focuses on design’s role in transforming natural resources into desirable products, offering a thought-provoking perspective on sustainability.

During the grand opening week of this visual feast, I met with the biennial’s curators to delve into the celebration of the moving image, set to unfold across the five floors of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève.

Nicolas Vamvouklis (NV): The Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement started nearly forty years ago in a completely different format, always placing the moving image at its heart as a ubiquitous medium in constant flux. What distinguishes this event and makes it uniquely relevant?

Andrea Bellini (AB): Our biennial is unique because, fundamentally, it is not just an exhibition but a production platform. We are not interested in showing existing works with new or seductive titles. Our adventure in the world of moving images is dedicated to producing new works. That is why we not only provide artists with the budget to create an entirely new piece but also accompany them in the production over the course of two years. I launched this format in 2014, and it has proven highly successful. Central to this approach is the idea of curators taking a step back. While we ask our co-curators to assist in artist selection, we refrain from imposing specific themes on the artists.

NV: This year’s edition is titled “A Cosmic Movie Camera.” Can you elaborate on the idea behind it?

AB: Three years ago, I decided this edition would explore the relationship between art and new technologies. That’s why I appointed Nora N. Khan as the co-curator. Through this exhibition, we delve into crucial questions about our relationship with artificial intelligence, how invisible images are used to condition us, and the complex issues surrounding algorithms that autonomously generate images, influencing our political, social, and economic behavior.

The exhibition, seemingly futuristic, actually tells us a lot about our present. It reveals stories of war, exile, and our fear of machines, but also about life and hope. Perhaps one of its most striking aspects is the need to experience life as a path of initiation and knowledge.

NV: So, you teamed up with Nora N. Khan for this new chapter. How did you collaborate on the development of the project?

AB: It was fabulous working with Nora. She is not just a curator but also a brilliant writer and essayist. For Nora — and for me, too — this was an initiatory journey during which we got to know each other and discussed issues that are anything but simple. Together, we selected all the artists, engaging in conversations and debates with great freedom and respect. This working relationship was very human and enriched me deeply. I learned a lot from Nora, perhaps more than she learned from me.

NV: The biennial’s opening coincides with the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. What plans do you have for this special occasion, especially in relation to designer Giacomo Castagnola?

AB: With Giacomo Castagnola, we conceived a project centered on the concept of ‘gift.’ Since this is the Centre’s fiftieth anniversary, we decided to donate all the catalogs, posters, and invitations produced in recent years to the public, without whom the institution would be an empty shell. We will retain only copies for our archive.

Thanks to Castagnola, this site of ‘gift giving’ is taking shape in harmony with the Centre’s exhibition spaces. In fact, all the shelves on which we’ve placed the catalogs we’re offering visitors develop around the metal cage of the elevator as if this were the spine of the institution, around which we display our own history.

NV: The overall Bâtiment d’Art Contemporain in Genève, where the Centre is housed, will soon undergo renovation and reorganization. How will your programming evolve during this transitional period?

AB: Indeed, starting in 2025, this building will be closed for a restoration that will last at least four years. We see this as an opportunity to reinvent the way our institution exists. Rather than renting a possibly smaller venue and creating a scaled-down version, we aim to experiment with something entirely new. Our plan is to collaborate with various institutions in Geneva and abroad, leading to the creation of an unprecedented project, one that, in a certain sense, aligns with teaching and learning. It’s too early to delve into the details now, so stay tuned. Something wonderful will happen!

NV: Nora, I would like to know more about the biennial’s concept, which is apparently connected to your research interests in algorithms, artificial intelligence, and machine learning.

Nora N. Khan (NNK): The Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement eschews the usual formula of a theme that artworks then ‘fit’ inside. Creating a concept that was light enough to ‘float’ alongside this group of artists – without being didactic – was a delightful conceptual challenge. Early on, I wrote a narrative about the most compelling threads emerging in the field, often described with a catch-all: ‘artists working with emerging technologies.’ The field has evolved quickly in ten years, moving past the novelty of, say, ‘training ML’ to include wide-ranging considered research about the changing nature of the moving image. I was drawn to artists gathering, sifting through the myths, theories, and ideology driving technological design, and humans living in the wake or shadow of these stories.

Given that overstories about technology – and what it is meant to do in the world – influence its design and, further, make it hard to see its actual impact – to see artists use these overstories as material has captured me. Artists invent, craft, and simulate ways to see the unseen – like conjurers, yes, but also like scientists, from data scientists to astrophysicists to game designers. They teach us to see what’s hard to discern and track in our quantified world – the immaterial forces that shape our language and sense of time. In the end, the biennial’s concept formalized as their works matured. Andrea and I share an interest in scientific discoveries about the event horizon. (My father is a theoretical physicist, so his work was about what is imperceptible to the human eye.) The term’ cosmic movie camera’ – a metaphorical gesture and potentially a real description – felt ideal for this wide-ranging group of artists. We need ways to create and represent what’s unseen with images, hallucinatory, constructed, and otherwise. These simulations have always helped us approach the unknown like a ladder spun and thrown at the void. The concept is meant to help visitors spin a few of their own!

NV: I am curious about the way participating artists and collectives were selected. How did you collaborate with Andrea on this?

NNK: While Andrea and I knew each other’s professional work, of course, the most generative collaborations come out of friendship based on mutual respect. The final artist list came about after months of conversation and discussion that anchored around viewings, visits, and close reading of the entire oeuvres of hundreds of artists. I admire what Andrea has made BIM into, and I was intrigued by the seeming total freedom given to the guest curator or curators and, in turn, to the artists. Eventually, I understood that BIM’s success and ambition are rooted in this belief in artists, in their greatest and headiest ideas, and following them, supporting them fully. We looked at artists at a critical turning point in their careers, whose works were reaching and moving to speak in new languages and were, in fact, having a massive influence on access to often gated and elite discussions about ‘technology.’ We visited exhibitions, discussed new and former works, and drew on our respective travels through art and para-institutional spaces. We thought, then, about what questions clusters of artists in the group spoke to and, all together, the holistic view of the entire group. What I’m particularly happy with is that though the individual artists in this group are often described with the same terms, many have not been grouped together. They make for a surprisingly vibrant and relentless group.

NV: All the artists have been commissioned to create original works for the exhibition. What challenges did you face in managing such a massive process, considering the specific nuances of the medium?

NNK: Having worked on massive commissions over a one to two-year span before, I was certainly keeping the potential traps and pitfalls in such a process in mind. In the art and technology space, you often work on seriously ambitious projects that are technically and conceptually demanding. They require us to work well between multiple registers. We invite the artist to draw on their dream project or an unrealized idea, and then must contend with: how do we ensure it works technically? What support and expertise will we need? Where have we seen an idea before, and what is the ideal install? What atmosphere is the artist hoping for in the space? How do we ‘move’ with their ideas, remaining as light in touch as possible? What resources are needed – what infrastructure, what staffing?

The gathered works discuss everything from speculative genetic legacy to the use of NeRF (neural radiance fields); so, how will education tie in? If there must be edits because of impermeable demands, how does the concept remain intact? Might we think of versions of a new work, this being the first of many? As the commissions take shape, we have a clear sense of the choreography emerging. One of the biggest challenges is momentum. As a curator, one is hopefully engaging with as many artists as deeply as possible, problem-solving, thinking through conceptual knots when they arise. My role is to be a helpful and productive mirror, not overstepping but offering insight and positive critiques. They are beautiful dialogues that become real. The challenges are entirely always worth it.

NV: I recall reading online that you like “studying the person before the machine, in relation to the machine, and inevitably thinking through the machine.” With this in mind, I wonder what you hope visitors will take away from the biennial.

NNK: In every exhibition, there’s always a question or two from visitors that stand out. One of my favorites, a few years ago, in an exhibition largely about women misusing technology; a visitor looked around at the ‘time-based media art’-inflected works on display, and asked, but why is this art? And we had a brilliant conversation in which I had to revisit my assumed frame and historical context about what art is. In the first week of the BIM’24 opening, I spoke to a few visitors for whom the ideas, aesthetics, and concepts were entirely new; they wanted to know why a game was an artwork or were inquisitive about the precise balance of narrative and research in each work. Others said they didn’t see much of the ‘moving image’ or not in the form they expected. I find these precise responses fascinating. When I spoke to many of the artists, our understanding and parameters for ‘the moving image’ today were necessarily vast: it could have been a reflection in a bowl of water; it could be the millions of synthetic images your phone produces you never see, distributed for training. There are many personal preferences and ideas about what art should be that audiences always bring to an exhibition. I’m frankly thrilled if a work does not first appear to be art, and then a conversation begins. Works made with or about technologies, especially ML and AI, have long faced this immediate rejection and strong feelings for good reason.

What I hope visitors to BIM’24 will take away is a set of inquiries about their relationship to systems in their own lives, which they can revisit and keep in mind in the tumultuous image years to come. I hope the range of examples of ‘moving image’ – constructed, synthetic, filmed, projected, generated, hand-drawn, animated – on display might expand the lens with which viewers consider the new, strange image world we’re now in, and use that awareness to bring a sharper critical apparatus to discern, evaluate, feel through, and debate what these images are telling us.

PHOTO CREDITS

1 Diego Marcon, La Gola, 2024

Digital video transferred from 35 mm, CGI animation, color, sound, 22’22’’

Courtesy of the artist, Sadie Coles HQ, London, Kunstverein Hamburg, Kunsthalle Wien, and Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24.

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

2 Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

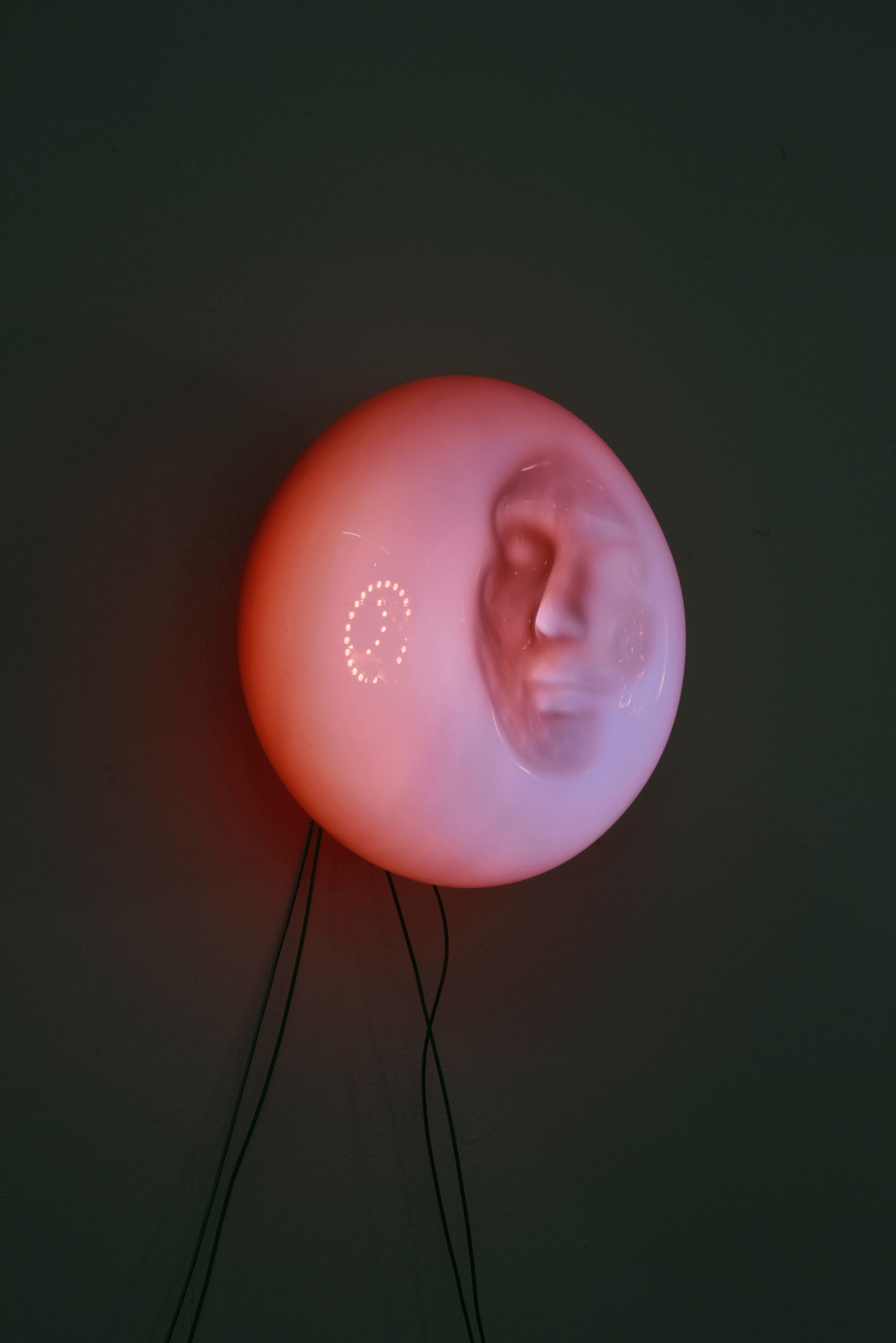

3 Jenna Sutela, Sharp wave, ripples, 2024

Five sculptures, blown glass, LEDs, microprocessors, wires, variable dimension

Courtesy of the artist & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

4 Alfatih, A Way Out of Time, 2024

Pram, real-time video of variable duration, full-time gallery attendant

Soundtrack by Tapiwa Svosve

Courtesy of the artist & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

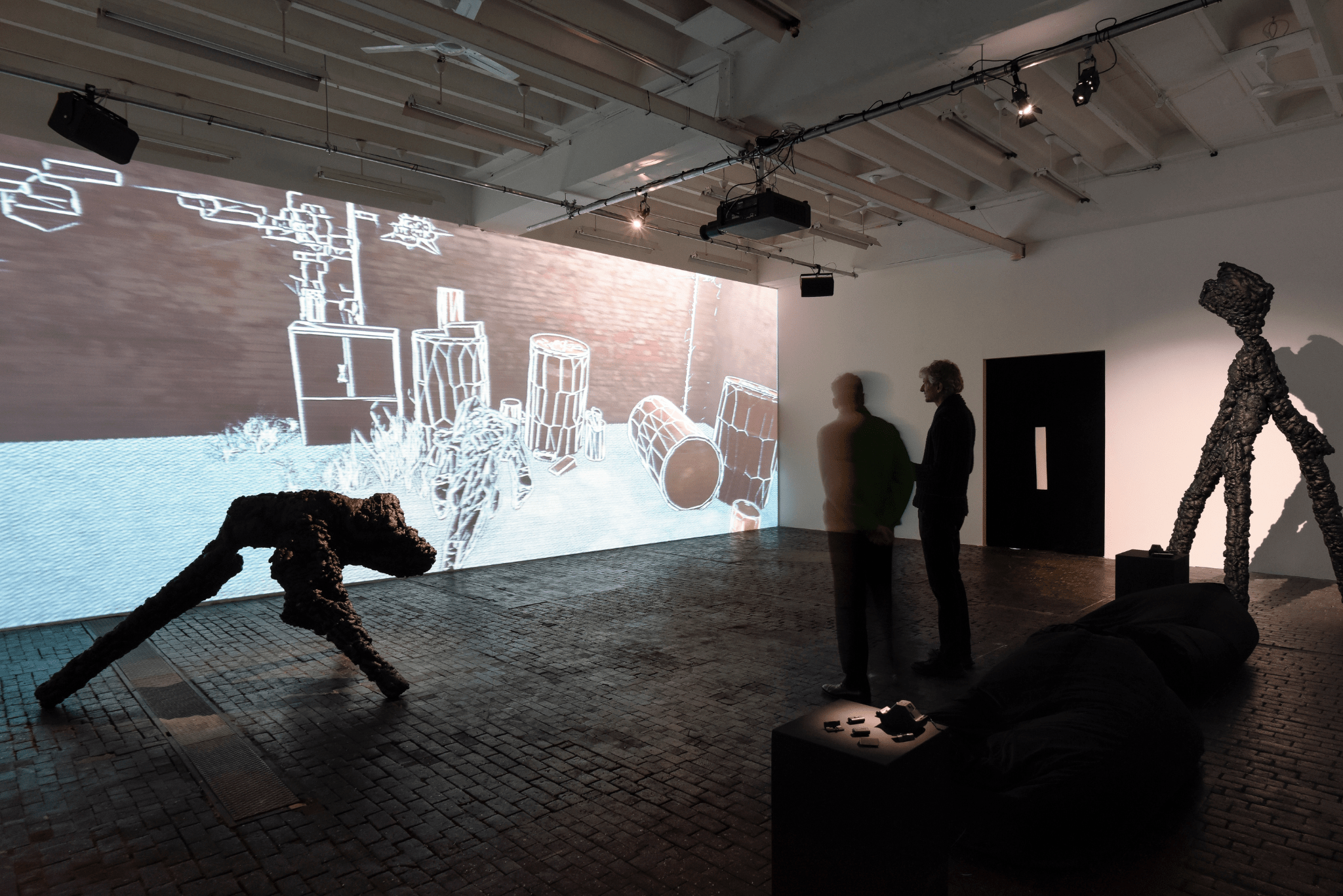

5 Sahej Rahal, Distributed Mind Test (DMT), 2023

Videogame, site-specific sculpture, drawings, installation, sound

Courtesy of the artist & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

6 American Artist, Yannis Window (still), 2024

Sculptural projection, single-channel 4K video with sound, 21’32”

Courtesy of the artist & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

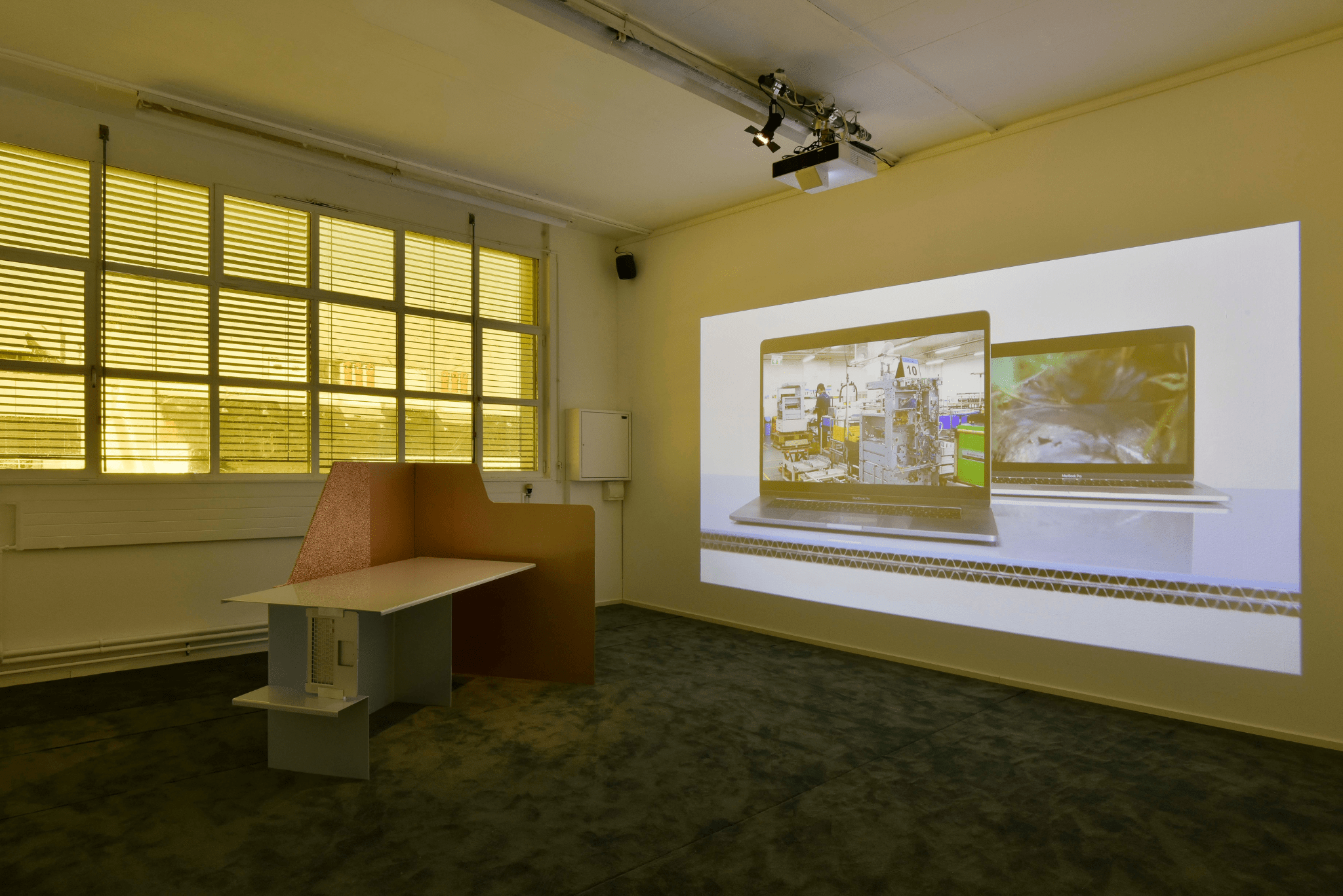

7 Formafantasma, Ore Streams, 2017-2019

Multimedia installation, variable duration

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

8 Lauren Lee McCarthy, Saliva Retreat (still), 2024

Digital video, 43’

Courtesy of the artists & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève

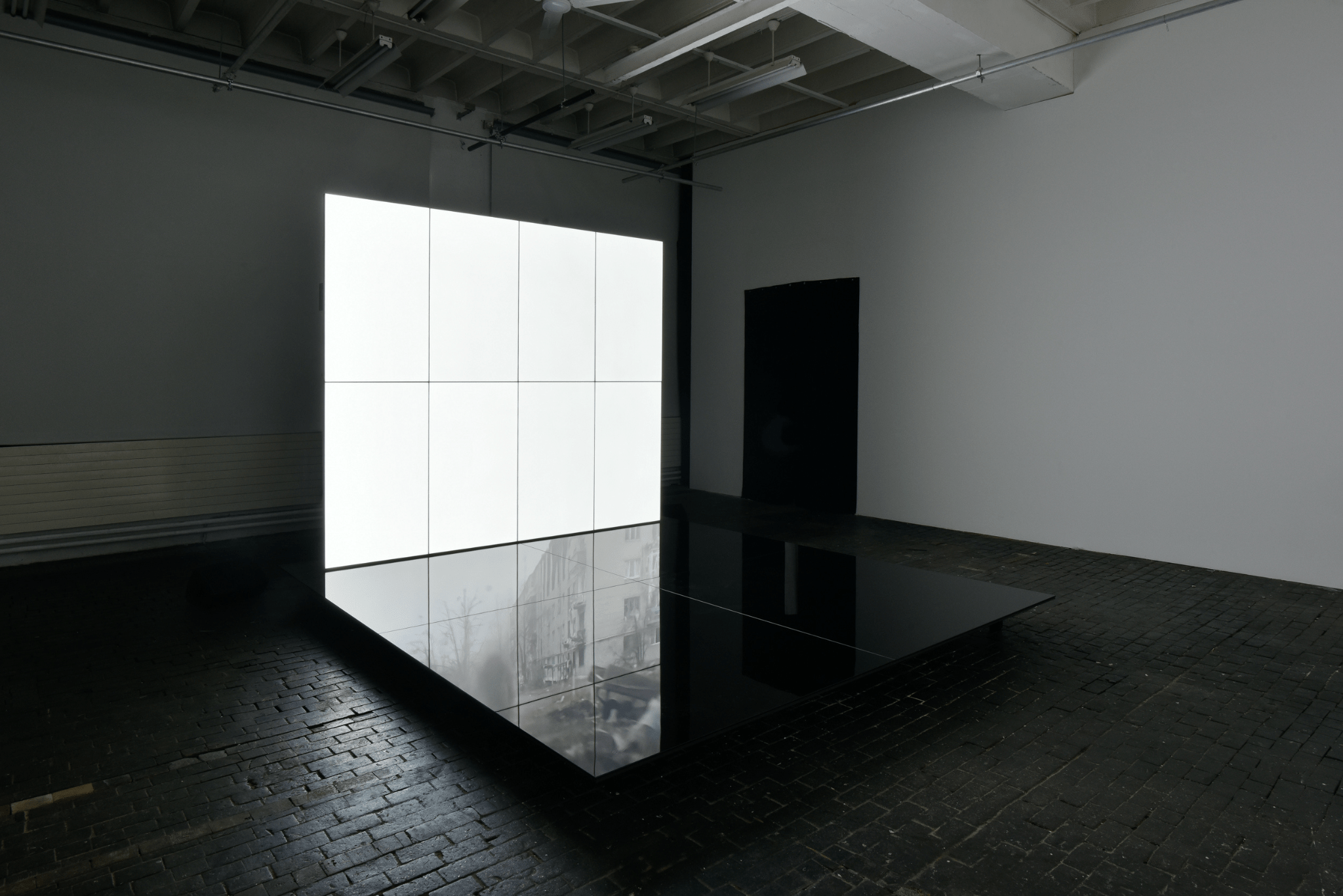

9 Emmanuel Van der Auwera, VideoSculpture XXX (The Gospel), 2024

Video installation, 17′ 53”

Courtesy of the artist, Harlan Levey Projects & Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève for BIM’24

Exhibition view of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement 2024, A Cosmic Movie Camera, at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève. Photo: Mathilda Olmi © Centre d’Art contemporain Genève