Antoni Muntadas and Francesco Jodice

December 2023

Antoni Muntadas is an artist who “looks at the world with intensity and curiosity”. Active since the 1970s, Muntadas’s projects address mass media, the mechanisms of power, censorship, manipulation and consent, political and social issues, and the relationship between public and private space.

Historical figure of critical art and multimedia artist, he translates various disciplines such as sociology and politics into artistic practice through video, photography, urban installations and the Internet.

Francesco Jodice is an Italian photographer who investigates transformation in the social landscape with a focus on urban phenomena, anthropology and the creation of processes of participation. His projects build a common ground between art and geopolitics, proposing artistic practice as a civil poetics.

We interviewed them on the occasion of their two-person exhibition Altrove/Elsewhere at Galleria Michela Rizzo in Venice.

ANTONI MUNTADAS

I would like to begin with a work of yours that is not in the exhibition, but which struck me because of its simplicity and depth. It is part of the cycle On Translation: Warning. It is a print on paper with the phrase ‘Warning: perception requires involvement’. So art as the perception of sensations and information and the work – again according to your definition – as an “anthropological activator”. You seem to be saying that perception always implies some form of involvement. Is this a way of uniting art and everyday life?

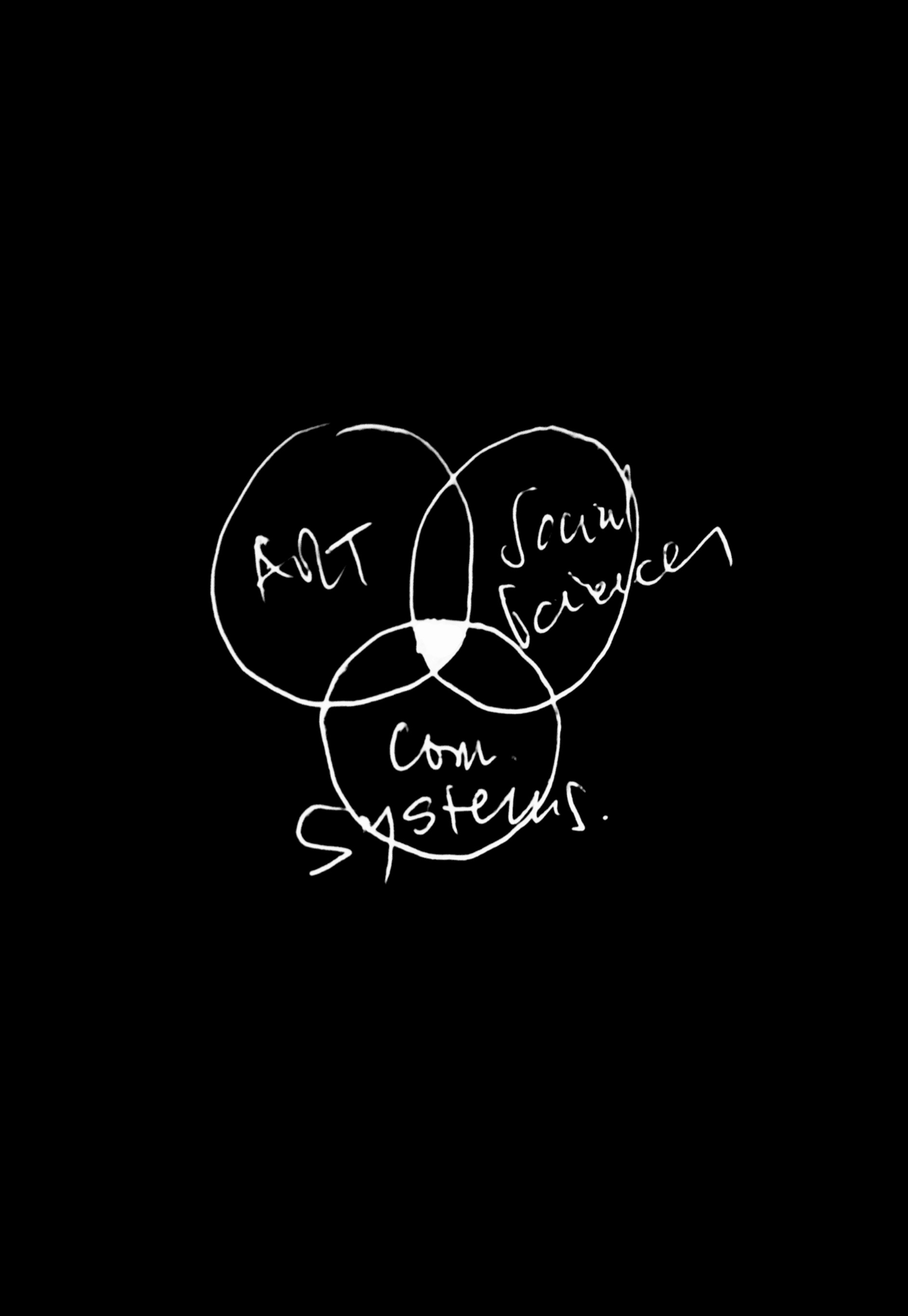

Over the years I have developed a way of translating my statements with diagrams that help me to order and define the field in which I move. In the 1970s, for example, I came up with this diagram of overlapping circles representing art, social science and communication systems. I placed my work at the intersection of these three areas, and I still do. Art practice is contaminated and hybridised by other disciplines.

Another diagram I made is art and life, to answer your question. The reference to the relationship between art and life is like an arrow going from one side to the other, but it is not an equality. I think art influences life and life influences art. There is a process behind it, like a slow readymade, where I appropriate external images for an ecological reason of reusing what already exists. Another key element is time, my work is never immediate, I am against quick production, my method takes time. This relationship between ‘perception’ and ‘involvement’, which works particularly well with words in English more than in other languages, serves to position my practice. The entire On Translation series considers the artist as a translator, and the warning that ‘perception’ requires ‘involvement’ becomes a leitmotif, because if perception does not imply involvement, you can see something, but you cannot fully understand it. Perceiving is digesting, responding to the idea that the gaze is the beginning of perception, which must be linked not only to the senses but also to personal, political and social engagement.

As you just said, you move between three ideal domains: art, social sciences and communication systems, locating your practice in the interstitial and overlapping spaces of these domains. In 1995, the American critic Hal Foster published the essay ‘The Artist as Ethnographer’, in which he reflects on how part of contemporary production is moving towards ethnographic study, becoming interested in archives, identity and subjective constructions, and moving from Western ethnocentrism to the postcolonial scenario. Certainly, Foster’s reflections were a reflection of globalisation, but also of the fact that pure images are no longer enough for us, we no longer trust them. As the American anthropologists George Marcus and Fred Myers put it: “Art is now occupying a space long associated with anthropology, becoming one of the principal sites for tracing, representing and performing the effects of difference in contemporary life”. What do you think?

In 1988 I showcased the exhibition ‘Híbridos’ at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid. When I decided on that title I was frequently asked how I could call my work hybrid? At the time, everything was seen as pure and complete in itself. But this idea of purity does not exist, everything is mixed and contaminated. At the time, Néstor García Canclini, an Argentine sociologist and good friend of mine, was about to publish an essay entitled ‘Hybrid Cultures’, which anticipated many issues that later emerged in the field of anthropology, and I was preparing this exhibition at the same time, an unexpected harmony. Symbols, icons, images are cultural objects that are relevant for several generations, we produce images linked to a precise time and space, I call them cultural artefacts in the anthropological sense, because they are remnants of a period that remains and that has a relationship with the context in which it was produced and with the time in which it was born.

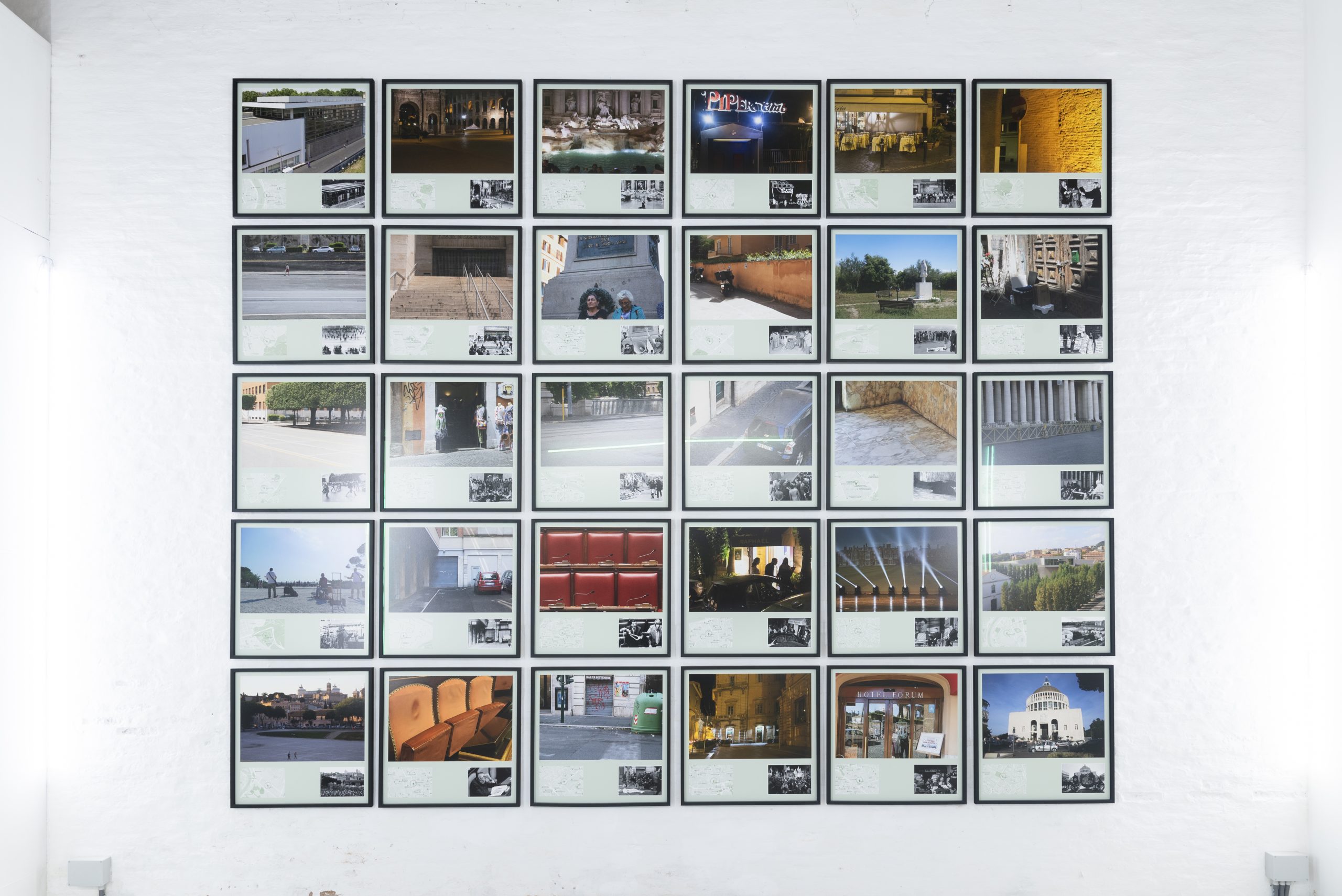

Similarly, the work in the exhibition is based on Rome: Media Sites/Media Monuments: Rome, is conceived as an artefact to read the history of the city through collective memory and media images, it is about the silence that comes after the media noise of an event has dissipated, which is why I titled it ‘Media Monuments’.

I identify myself as a post-studio artist in the sense that I do not need a studio to work in; I use research, fieldwork, interviews and conversations, and visits to the places where I work. The traditional artist, on the other hand, did not need such a long research phase. Obviously this strand was born in the 1970s with conceptual art, when people started to be interested in content, in the processes of creation, and the artwork was the residue of the project you were doing. My works are very time-bound, they are never immediate, which is why I hate deadlines, because works are linked to research and the work materialises only when it is needed. In general, I am against exhibiting archives and research material, because these elements feed the work, but they are not the work. The artist is responsible for the editing, the selection of the material, the editing is the combination of all the selected material and eventually it creates the work.

Altrove/Elsewhere is the bipersonal exhibition featuring your works and those of Francesco. How did the idea of doing an exhibition together come about? How did you and curator Bartolomeu Marí develop the conceptual arrangement and exhibition selection?

The exhibition is the result of the work of the curator. I divide curators into two types: there is the fast curator and the slow curator. The ‘fast’ curator is a fashionable curator, a figure who has emerged in the last two decades. They appropriated Szeemann’s practice, he was ‘slow’, but many of those who are now independent curators have an immediate, ill-considered practice, with little research behind it and little dialogue with the artists. Bartolomeu, on the other hand, is slow; he curated the Spanish pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale, where I exhibited the series On Translation.

I first saw Francesco’s work at a group show in Bogotá, I really like the way he collects all these oral histories and turns them into videos, we have a mutual interest in our research, then knowing that Michela Rizzo works with both him and me, we thought of doing an exhibition together. We chose the curator together, but I didn’t know where we would go from there. Especially in an exhibition with more than one artist, it is the curator who has to take care of the selection and the relationship between the works, and then it is up to the viewer to see whether they work or not. I like the dialogue between our works because our themes are close: globalisation, the city, architecture, the media.

Both you and Francesco have worked on the theme of inhabiting the city. I am thinking of your series Alphaville on São Paulo, which deals with gated communities, and Francesco’s series What We Want and Citytellers. The city as a container of differences, contradictions, but also solutions, as a metaphor for globalisation, economy and society. These are works that show the contradictions and mechanisms of power through fear and desire. You are very interested in showing these aspects in your work.

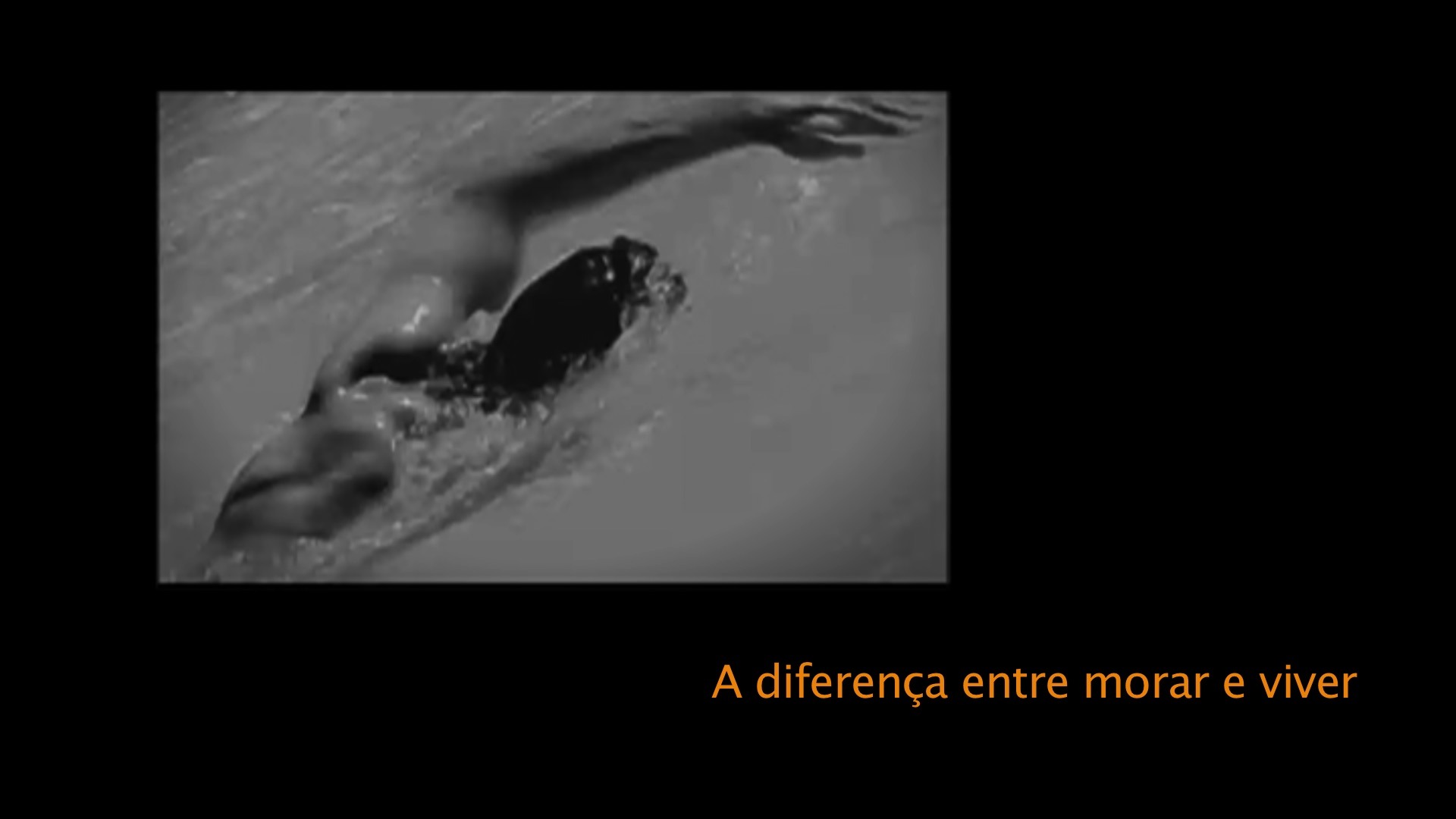

Cities are where I live, where I move and where I observe the world. Since I do not have a studio, I work where I am and then realise everything in a workshop. The works are literally made elsewhere. From my urban experience it is clear that you cannot approach the city as a whole, but only as fragments. Every time I work on the city, I realise a partial view of a question or an aspect that I am interested in exploring. The work always begins with a curiosity to find out more. In the case of Rome, I wanted to find out more about the city by investigating its media memory. Alphaville, on the other hand, deals with a lesser-known aspect of Brazilian cities; people always talk about the favelas, but very little about the community life of the upper middle classes who live in these gated communities, where they think they are living free, but which are actually like prisons. So the title refers to Godard’s film; this film, along with Tarkovski’s Stalker and Chris Marker’s La Jetée, are films about utopian or dystopian spaces, ambiguous spaces, like the space of Alphaville, which is the name of the film, but also the neighbourhood of Saõ Paulo, it is a fictional utopia of an exclusive community.

So all relationships with architecture and the city are also fragments of everyday behaviour, such as people in queues; my series Protocols, set in different parts of the world, examines how we organise ourselves socially in the world. On the other hand, Arkitektur / Räume / Gesten I is a commentary on architecture understood as the result of a process of working from an idea and a gesture; they are triptychs that bring together these gestures, the space where the negotiations were made and the architecture that is the end result. I reflect on the cultural, landscape, economic and socio-political reasons that made this building what it is and how it is. Rather than defining a work about the city, I make observations about how cities look. In a series called Situationes I collect the movements of people in the city, or the series on airports, because I spend a lot of time there. They are all fragments, I always work in series, like images of frames that follow each other, what I do is a moving process.

What are you currently working on? What projects are you pursuing?

I am planning an exhibition in Hong Kong where I will present a local version of Media Sites/Media Monuments. So far I have done it for Washington, which is a city of monuments, Budapest after the fall of the wall, Buenos Aires and in 2017 in Rome. I am interested in Hong Kong because of the many transitions it has undergone: from a Chinese city to a British colony and, since 1997, back to Chinese and, more recently, for public events. This is my way of getting to know the city. For the last thirteen years I have been developing Asian Protocols, which relates the cultural and political dimensions of China, South Korea and Japan.

Then I have a commission in São Paulo, where I was asked to make an intervention at SESC Pompeia, the building designed by Lina Bo Bardi. It is a very interesting place that combines a cultural centre, a cinema, a swimming pool and a sports field, and it is a real challenge for me. Then there are the series of works I do for myself, such as the series On Translation, which has more than fifty sub-projects, where I am interested in exploring other aspects of living in the city, the question of language and popular sayings.

FRANCESCO JODICE

In the exhibition, the dialogue between your works and those of Muntadas reveals an approach that is thematically similar but genetically different. While Muntadas has an almost scientific methodology in his projects, in yours, although equally methodical, the margins are more unstable and the works are more open. You said that your works are designed to be misunderstood; they are irresolute because they do not answer questions but, on the contrary, “raise doubts”. You always seek a certain discomfort of perception, and the aesthetic is always taken into account. For you, what is the relationship between the aesthetics of a work and the ethics behind its creation? Is it more important for art to make you understand or to make you feel?

I am interested in the ‘position of the spectators’, the role we assign to them. In recent years, my work and, more generally, the procedural tactics that I stage have focused on participatory models, with particular attention to the role of the audience, or rather the audiences. I try to place the viewer in a disconcerting and unbalanced position; when confronted with one of my works, I want them to ask themselves: “What am I looking at?”.

I want to create a feeling of mistrust and suspicion towards the works, and that, in some way, these feelings help to formulate questions about our time with awareness. To the question of whether it is more important for art to make us understand or to make us feel, I would say that art should help us with our posture, to get up in the morning and walk upright.

The Room and What We Want, two of the projects on show, began as portraits of the social landscape, the former by selecting sentences from the front pages of local newspapers and blacking out everything else. The second is an ongoing project consisting of the accumulation of photographs from over 170 cities around the world. Both you and Muntadas depict urban contexts, their use and the changes they undergo in order to read the projections of their inhabitants’ desires. It is a way of mapping change and comparing phenomena in different parts of the world. Given the chronological nature of these two projects, is this also a way of measuring change in a society over time?

I think the dates are important: What We Want is an atlas of photography begun in 1996, The Room is a work of erasure and ‘misrepresentation’ of texts begun in 2009. The interval between the two works shows (my) growing and inevitable sense of mistrust in the medium of photography. Both projects speak of the modification of the landscape and the contextual modification of the language we use to interpret and represent the mutations of social, cultural and generally geopolitical landscapes. I believe that a possible convergence in Antoni’s and my processes is the habit of perceiving society and the time to which it belongs as an anomaly; a digression or deviation from a path that could have been more congruent and coherent with hopes and hypotheses that have been disregarded. I also believe that we both work as “movers”, we do not impose a pedagogical and ethical vision, but rather we translate such anomalies into the view of the public, asking them also to confront the aberrations present in the system.

The French sociologist Henri Lefebvre teaches us that architecture is not just a backdrop, but it affects us and produces social relations. I (also) read this reflection in between the lines of the last work in the exhibition, Falansterio. A series of photographs of the most famous examples of social housing in Italy, from Corviale to the Vele, to ZEN in Palermo. The title refers to the model of the micro-society theorised by Charles Fourier at the beginning of the nineteenth century, where he hypothesised collective and cooperative life in large buildings. Is this work about the failure of utopias?

I’d like to tell you an anecdote about the role of architecture. Many years ago, a famous anti-mafia magistrate from Naples told me: “Today Camorra is mainly an urban problem”. As far as the Falansterio project is concerned, it was born from the desire to tell the story of the aspirations and failures of the Italian left, and how it was the last political faction to believe in architecture as a means of building a cohesive and ideologically inclined community and collective good. Falansterio is also the story of the transformation of political architecture into mausoleums of decaying ideologies.

In a previous interview, you talk about the three traumas that photography has faced in recent years: the disappearance of the photographic camera, replaced by smartphones; the disappearance of photographic printing, replaced by social networks; and the disappearance of the photographer. Despite all this, photography as a tool has proliferated exponentially. How would you interpret the current situation?

All languages are dying. Cinema, painting, performance, theatre, comics, sculpture or photography. But they are also an Arab phoenix, and are resurrected through transubstantiation. Photography has made an epic comeback, resurrecting itself in the form of the selfie. According to a 2022 study, around 200 billion selfies are taken every year. Saskia Sassen had written that the end of universal ideologies and the conflict between capitalism and socialism had led to the era of ‘mass individualism’, a wonderful oxymoron. Photography is fine, I think, it’s just distorted: once there was a rule that the author and the things observed had to be on the opposite sides of the darkroom, now the observer and the observed are one. We have blocked the lens and there seems to be nothing left to see behind our self-portrait.

What codes are you currently interested in investigating? Which waves do you tune into? I wonder what you’re currently working on.

I just finished a long visual story (2014-2022) about the rise and fall of the West entitled WEST. I don’t have a clear idea of what to do next even though I am aware that this is an incredible and terrifying time. A phrase by Coetzee from the book The Barbarians Are Coming comes to mind: “Something stared me right in the face yet I still can’t see it”.

PHOTO CREDITS

Installation view Altrove/Elsewhere, Galleria Michela Rizzo, 2023

Antoni Muntadas, Diagrama 3 circulos, 1973. Courtesy of the artist

Antoni Muntadas, Arte = Vida, Poner flechas entre el arte y el vida, Barcelona 1974. Courtesy of the artist

Antoni Muntadas, Media Sites/Media Monuments: Roma, ink on photographic paper, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Michela Rizzo

Installation view Altrove/Elsewhere, Galleria Michela Rizzo, 2023

Still from Alphaville e outros, video, audio, 2011. Courtesy of the artist

Installation viewi Architektur / Räume / Gesten II, 1988-2017 at Art Basel, Basel, Poligrafa Obra Gráfica, 2018. Ph. credit: Marta Muga

Installation view Situations, 2008, at Entre/Between, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2011. Ph. credit: Román Lores Riesgo; Joaquín Cortés

Antoni Muntadas, On Translation: Warning, 1999 – 2005, at Spanish Pavillion, 51° Biennale d’Arte Venezia, 2005. Courtesy of the artist

Francesco Jodice, What We Want, Hong Kong, T47, digital print on Alu-dibond, 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Michela Rizzo

Francesco Jodice, Falansterio, 2020, ink and colors printed on cotton paper. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Michela Rizzo

ANTONI MUNTADAS

Antoni Muntadas (Barcelona, 1942). He lives in New York. He has been researcher at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT (1977-1984). He has taught and held numerous seminars at various European and US institutions, including: National School of Fine Arts, Paris; Schools of Fine Arts of Bordeaux and Grenoble; University of California, San Diego; Cooper Union, New York; University of Buenos Aires. He was Visiting Professor at the Visual Arts Program of the School of Architecture of MIT in Cambridge and at the IUAV University of Venice. His works have been exhibited in numerous museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Berkeley Art Museum in California, the Musée d'Art Contemporain de Montreal, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Museo de Arte Moderno of Buenos Aires, the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro and the Museu d'Art Contemporani of Barcelona. He presented works are the VI and X editions of Documenta Kassel (1977, 1997) , the Whitney Biennial of American Art (1991), the 51st Venice Biennial (2005), and other biennials in São Paulo, Lyon, Taipei, Gwangju, and Havana. Muntadas is particularly known for his projects that involve the artistic use of media and new media for social and political function. Over the course of his career, he has measured himself with photography, video, publications, the internet, installations and urban interventions.

FRANCESCO JODICE

Francesco Jodice (Naples, 1967). He lives in Milan. His artistic research investigates the changes in the contemporary social landscape, with particular attention to the phenomena of urban anthropology and the production of new processes of participation. His projects aim to build common ground between art and geopolitics, proposing artistic practice as civil poetics. He teaches at the two-year course in Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies and at the Master in Photography and Visual Design at NABA – Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan. He was one of the founders of the Multiplicity and Zapruder collectives. He has participated in large group exhibitions such as Documenta, the Venice Biennale, the São Paulo Biennial, the ICP Triennial in New York, the second Yinchuan Biennial and has exhibited at the Castello di Rivoli (Turin), the Tate Modern (London ) and the Prado (Madrid).

ANTONI MUNTADAS

Antoni Muntadas (Barcelona, 1942). He lives in New York. He has been researcher at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT (1977-1984). He has taught and held numerous seminars at various European and US institutions, including: National School of Fine Arts, Paris; Schools of Fine Arts of Bordeaux and Grenoble; University of California, San Diego; Cooper Union, New York; University of Buenos Aires. He was Visiting Professor at the Visual Arts Program of the School of Architecture of MIT in Cambridge and at the IUAV University of Venice. His works have been exhibited in numerous museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Berkeley Art Museum in California, the Musée d'Art Contemporain de Montreal, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Museo de Arte Moderno of Buenos Aires, the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro and the Museu d'Art Contemporani of Barcelona. He presented works are the VI and X editions of Documenta Kassel (1977, 1997) , the Whitney Biennial of American Art (1991), the 51st Venice Biennial (2005), and other biennials in São Paulo, Lyon, Taipei, Gwangju, and Havana. Muntadas is particularly known for his projects that involve the artistic use of media and new media for social and political function. Over the course of his career, he has measured himself with photography, video, publications, the internet, installations and urban interventions.

FRANCESCO JODICE

Francesco Jodice (Naples, 1967). He lives in Milan. His artistic research investigates the changes in the contemporary social landscape, with particular attention to the phenomena of urban anthropology and the production of new processes of participation. His projects aim to build common ground between art and geopolitics, proposing artistic practice as civil poetics. He teaches at the two-year course in Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies and at the Master in Photography and Visual Design at NABA – Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan. He was one of the founders of the Multiplicity and Zapruder collectives. He has participated in large group exhibitions such as Documenta, the Venice Biennale, the São Paulo Biennial, the ICP Triennial in New York, the second Yinchuan Biennial and has exhibited at the Castello di Rivoli (Turin), the Tate Modern (London ) and the Prado (Madrid).