Where things happen #22— April 2024

Mexican artist Berenice Olmedo works on an interesting, and not yet enough explored, intersection between art, medical technologies and inevitably related biopolitics.

All her artistic research originates from a fascination with the marginalized body, human or otherwise, which made her question who decides the standards of these categorizations of healthy, normal, or otherwise dis-abled. Having been following her practice for a few years, it was an honor and pleasure to finally visit her studio in Mexico City during the art week last February.

So, also in this month’s studio visit we report from Mexico, which proves to have one of the most interesting emerging art scenes and artists to discover, right now. Berenice welcomes us with her restless smile, and all her spontaneity. Her studio is in a multifunctional building, we would later discover in our conversation: as often happens in the big metropolis, the building is inhabited by different activities, from a guy working with metal, to fashion and even eggs farming.

She’s full of a contagious enthusiasm as she walks us in her spacious and luminous studio, and introduces us to some of her latest works and researches. Stacked in different shelves, we can observe what she calls “orthopedic garbage”, namely different prosthesis and other extensions or integrations meant to “correct” our body. Those are usually thrown away in a medical industry, with a clear waste of plastic resources and materials, which the artist instead recovers to convert those materials in some oddly shaped forms, which might recall us fetus, parts of organs, or some unsettlingly alien presences.

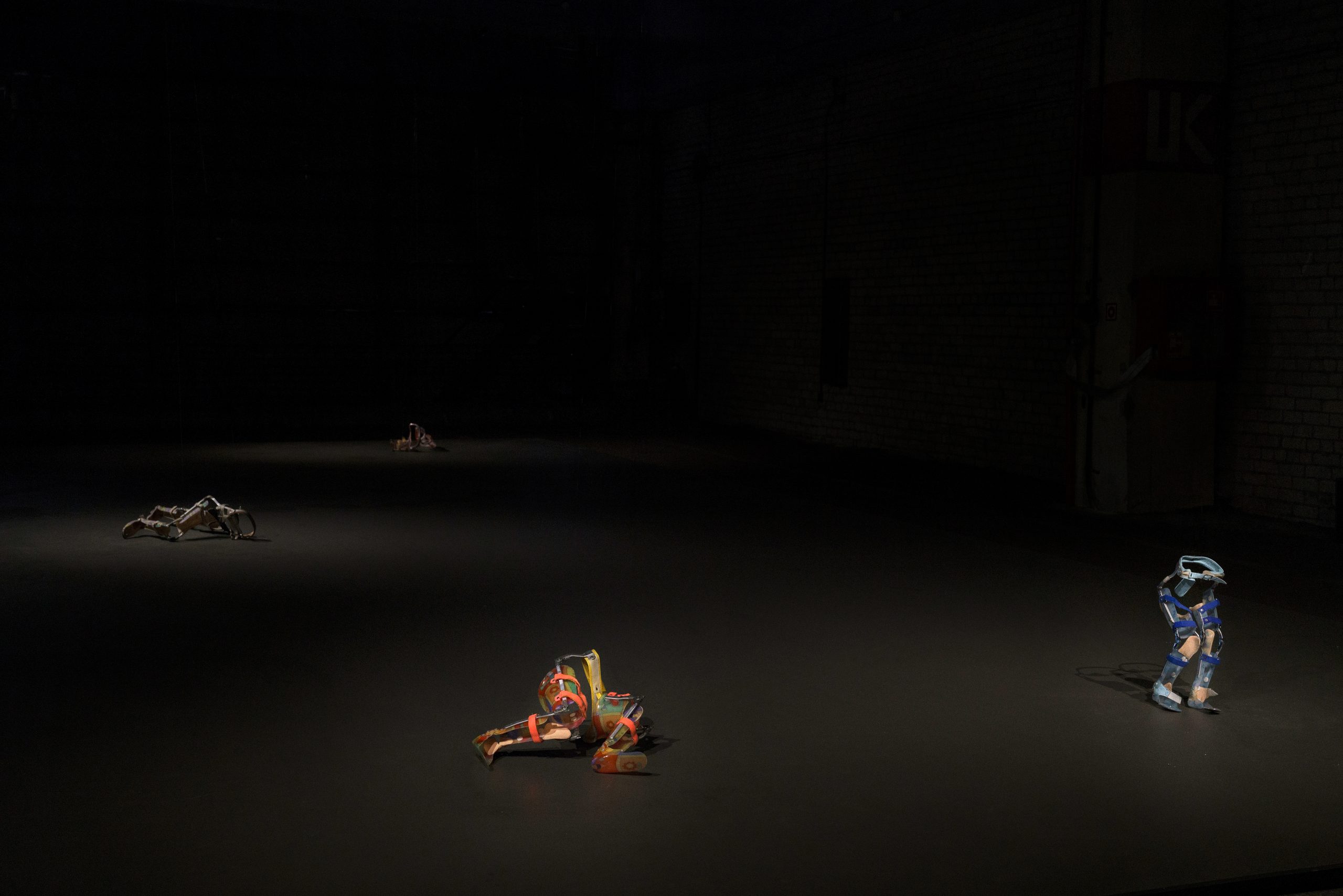

Engaging with these obsolete medical tools which have already depleted their function, the artist reassembles them in sort of post-human figures: sometimes they turn into robots and new futuristic creatures, other times they voluntarily maintain instead the fragmentary nature of carcasses or shells, waiting for a new life circle.

As Olmedo explains to us, in engaging with these materials as her medium, the artist wants to explore the possible change of functions of these extensions or substitutions of the body: such devices, created to replace missing body parts, or assist what is perceived as malfunctioning, are repurposed to challenge the notion of deformity or inadequacy that deem certain bodies.

Sometimes paradoxically reassembling those in new configurations, Olmedo’s works inspire a reconsideration of the bodies as fixed psychological and physical wholeness.

Through this visionary exploration of alternative topographies and taxonomies of the body, the artist in fact challenges all established cisheteronormative frameworks, opening some relevant question on what is “normality” or “disability” of a body, what it means “health” and “care” and who establishes the criteria and the resulting normative regime of corrections, modifications and medically imposed adaptation.

Yet, this analysis feels even more on point and powerful as it originates from the leftovers of a welfare state in a place like Mexico where, as many other countries, vast swaths of the population are still without adequate access to the kind o medical attention, healthy diet, and care needed to maintain such standards. But there’s always the private treatment option, which makes bodies even more subjugated to the both economical and political power of the medical and pharmaceutical industry, which we all had a chance to experience over the pandemic period.

At the moment of our visit, throning in the middle of the room there were some weird robotic creatures. Joking with us, she says that she actually had so much fun in casting and reassembling the different parts to build those bodies, starting from different molds and prosthesis tests. Also the material used for casting belongs to the medical industry, using the same silicon employed for actual prosthesis and sockets tests. As she admits, it hasn’t been easy to figure out how to creatively use these materials in the first moment, but she’s now working closely with the same professional manufacturers that produce for the medical industry, hacking their usual process to explore new combinations. The process of molding a socket is actually an art itself, which requires great skill of a prosthetist as the socket will need to conform perfectly to the patient’s stump.

One way to create a prosthetic socket is, for instance, by using the bubble-forming method: a thermoplastic socket material is heated in an infrared or convection oven until it starts to drop into a bubble-like shape. This bubble is then pulled over a positive mould of the patient’s stump and is left to harden completely, resulting in a socket that neatly conforms to the person’s contours with a comfortable and secure fit.

In making those sculptures, Olmedo applied this exact same procedure, despite now they’re meant to fit just other parts in an unusual, yet revelatory new configuration. Next, Olmedo says she would like to find a way to not be bound in terms of colors to what currently used in the medical field, but rather able to control those and play with pigments and gradations in order to make the sculptures closer to an epidemic effect, or rather totally alien to this world. The choice of translucency, however, might always remain both material and symbolic a key element for the artist, as a way to embrace and embody Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’ notion of “becoming-imperceptible” as a counter strategy to modern societies’ management of human life.

Moving to her computer, she shows us how she’s actually starting to design her own sculptures using professional medical softwares, which allows to further explore the possibilities to redesign these medical devices, as well as the body parts and functions they assist. She explains that so far she had to train herself on this complicated softwares so she is still mostly exploring, as she was lucky enough that some friends shared with her, but she is still waiting for them to help her to better navigate all the functionalities.

Presenting us her rehabilitation clinic archive of prosthesis molds, test sockets or other orthopedic tools, she makes us observe also how many of them still have the name of the people they were made for, on them, which sometimes also turns into the name that the artist gives to her sculptures.

In this way, the works engage with a sort of personality, which deprives them of their aseptic aspect and original functionality. Observing one closely it’s also interesting to note how Olmedo has here purposely engaged with tools made to “correct” children’s orthoses: despite the playfulness of the surface animated with cartoons to make them less scaring for the child, it’s inevitable to reckon some sort of violence on these instruments, made to “regulate” these small and young bodies, constraining their experience of the world and their movements into these uncomfortable body cages just to make them adequate for the current medical and societal standard of a healthy and normal body.

Throughout Olmedo practice all these medical devices and orthopedic objects turn into new uncanny bodies, which often escape the “correct” organization and functionality of the body parts, as we conventionally conceive them. Olmedo wants in fact to present even this dysfunctionality as a possibility, an alternative to the standard. As she commented once in an interview: “Historically man—white, heteronormative, adult, able-bodied—has been privileged as the universal norm against which everything else is measured, making women, children, queers, disabled, animals, plants, and molecules the ‘other.’ But as beings made of tissue and fluids, we must tear the notion of the body away from an anthropocentric hierarchy that places ‘man’ at its pinnacle and regard the body as a site for an encounter with that cate-gory’s other. There is no stigma of disability in the world I propose, but only variations of existence, variations of movement, variations of slowness and speed.”

And if we think for a minute, however, it has been also scientifically proven, how adaptive and compensatory allow organisms to reorganize often their functions around some deficiency, simply potentiating other abilities, senses or body functionalities. These evolutionary and adaptive mutations are still something not something much contemplated in current medical standards, preferring more invasive methods of resolutions of these deficits. Olmedo’s work seems instead to encourage a positive exploration of neural reorganization, as an opportunity for a change, thanks to the inherent plasticity of our body and brain organization in interacting within a multisensory world.

It’s indeed quite fascinating how the artist is also looking to integrate actual robots for orthopedics, in her work. Activating an entire arsenal of medical knowledge and devices into art making, the art of Olmedo has the potential of envisioning sometimes also new solutions for new possible developments, but at the same time is still critically questioning the nature of what it is to be human within the framework of possibilities of those technological revolutions.

This will be the case, again, for the new project she was currently focusing on, in preparation of a Biennale in Brazil. This new series of work will follow the line of her fascinating solo show Hic et Nunc held in 2022 at the Kunsthalle in Basel, Switzerland where she presented a constellation of clear plastic cocoon-looking bodies, made from various casts of leg stumps.

Here was were Olmedo started to explore how to mechanize her works to mimic some of the recuperation techniques she was being taught during a long bed bound period of convalescence, after a serious car accident earlier that year: she worked with a Japanese scientists to develop a small robotic element based on the electro stimulation therapy she received, to created a machine that would stimulate movement of the limb-sculpture at different points, resulting into a idiosyncratic movement that makes these objects feel alive. In the new body of work, she reveals that she will focus instead on the cardiac rhythm, mechanics, dynamics and medical interventions, conceiving these new works in close dialogue with a cardio specialist.

To close, this conversation about past and current projects made us clear how Berenice Olmedo art importantly forces us to confront some major questions regarding the normalization and control of bodies in our society, by creating a powerfully dystopian or visionary futurist anthropoestetic that challenges directly today’s biopolitics around bodies, and all the standards and norms that mercilessly regulate them. Olmedo locates biopolitics as inherently connected to capitalist notions of security, health, and efficiency, which are necessarily regulated by dynamics of power and unequal distribution of both resources and possibilities.

The work of Olmedo engages therefore in a critical commentary on the political dimensions of disability, illness and care, while encouraging us to contemplate already a somehow positive notion of “mostruosity”, seen as a possibility for an alternative evolution, similarly to what once anticipated by Derrida, as “a figure of the future, that which can only be surprising, that for which we are not prepared, you see, is heralded by species of monsters. A future that would not be monstrous would not be a future; it would already be a predictable, calculable, and programmable tomorrow. All experience open to the future is prepared or prepares itself to welcome the monstrous arrivant”