Features #17 — March 2023

BERLINDE DE BRUYCKERE IN CONVERSATION WITH NICOLAS VAMVOUKLIS

Berlinde, your new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth is entitled “A simple prophecy.” Which is the foretelling in this case?

The title is always essential in the research because it answers my question: ‘what is this all about?’. You can see two groups of work in the exhibition: one is related to “Arcangelo,” and the other to the “Enclosed Gardens.” They both address religious themes. I try to deepen into these ideas and make them human, to feel the value of things and what we can actually use today.

Everything related to the divine, the realm of the prophecy, is complex, obscure, and never fully accessible to the human mind. The word ‘simple’ in the title belongs to the human world; it’s our territory. It’s intriguing to me to connect the divine and the human, the religious and the profane.

Prophecies look into the future. Do you feel optimistic about what is coming up?

It’s hard to say that I’m optimistic, but despite the difficulties, I’d say it’s a fascinating era. If you look at the past, there have always been fluctuations both on the economic and socio-political level: what is going well today can go down tomorrow and vice versa. In my work, I try to provide a sense of hope and connection, an invitation to go through things together, whether happy or sad. We have many things to consider now: the pandemic, the war, climate change…

I hear that many people don’t read newspapers or watch television anymore. This choice to disconnect is strange to me. When you don’t relate to current events and what happens around you, you live in a big bubble and are no longer from this world. I insist that artists give perspective by mirroring their surroundings and providing alternative views. It’s up to you whether you look in that mirror or look away.

The works in this show delve into the human quest for transformation, transcendence, and reconciliation in the light of mortality. How do these three ideas interconnect throughout your research?

If you look at the works with these words in mind, I think you can feel what I’m trying to say. It’s sort of self-evident. Speaking about mortality, this lying figure (“Liggende – Arcangelo I, 2022-2023”) wasn’t created as a dead angel. He went down because he was tired; occupied with all our fears, problems, and secrets. It was too much for the angel. He just needs some rest to recover and move on.

My choice to use old materials that had their own lives and deteriorated through time showcases the wounds of what nature, time, or human intervention can cause, instead of hiding them. To remember the impact we have on our physical environment. In this work, the wax figure and its base have been ‘treated’ in the same way. They have an identical texture as the one continues into the other. It’s not merely a way of displaying the angel; the two parts became one sculpture.

On the other side, we have the two “Arcangelo” who have a particular connection with the plinths; they stand on their toes in a delicate, almost fragile posture. You don’t know if they are out of balance, if they will fly, or have just landed. It’s up to you what you see or feel.

You once said that working in the studio is like meditating. A sort of remedy. How did the pandemic inform the way you work there?

This new “Arcangelo” series came from that period… when I returned to my studio and had to work alone, since we were not allowed to work with a team. At that time, I was far away from figuration in my practice. I had not made any figures for a decade – I was quite convinced I was done with that. The pandemic confronted me with my body, its limits, and its fragility in an overwhelming way. To address the human figure again in one way or another felt like a necessity, so these works were born out of this process.

During my first lockdown in Italy, I remember posting on Instagram a photo of your sculpture “Spreken” I took a couple of years ago at the Istanbul Biennale. Two persons are hidden under blankets, which form a kind of second skin. What does protection mean to you?

The works “Spreken, 1999” and the so-called “Blanket Women” are visually similar to what we have here at Hauser & Wirth. At the end of the 1990s, I was interested in the ambiguous power of the blanket. The blanket as a universal element of protection and comfort, a basic shelter even in the worst of circumstances, but at the same time, one of suppression and suffocation, like in “Spreken, 1999”. The patterns and colours of those blankets are very recognizable and offer a sense of intimacy and familiarity. In the “Arcangelo” pieces, the figures also wear a cloth, but it’s a bronze and lead cast of animal skin that opens up to a completely different reading. The animal skin that once protected the animal as a barrier between its weak inner parts and the outer world is used here in an unfamiliar, abject way. I did the molding on cow skin to get a sense of heaviness; a heaviness that is emphasized even more in the choice of material, the lead: a burden that is almost too much to bear. A visitor told me that when he saw the angels, he waited for the moment they would throw away their heavy cloth to fly away. Nevertheless, I think the idea of protection and consolation is present in the angels. Their resilience and facelessness allow us to project our burden without being judged.

Speaking about physical or spiritual protection, I’d like to know more about your long-standing interest in Christian iconography. How do you approach the religious connotations in your practice?

The affinity with Christian iconography goes back to my childhood when I was surrounded by these themes in school. First by the images, only later I gradually learned the stories behind them. The images often exceeded my imagination in their brutality and explicitness. I think they helped me not to shy away from the unpleasant in my practice. The attraction to these images very quickly developed from the mere interest in what was depicted to an in-depth research of the artistic qualities of the works I encountered as well as the universal character of these images: the pieta, the body of Christ, are images of human suffering to me, which stretches far beyond the religious context. From the early years on, I’ve used these images, like a hanging body, referring to the crucified Christ, but brought to a more universal context. For example, in the first show I did here in Zurich, “Jelle Luipaard, 2004” was hanging from an iron beam attached to the wall.

A yellow leopard?

Jelle Luipaard. Τhat was the sculpture’s title and the model’s name. I always did that, naming my work after the model. Their character or mentality was somehow incorporated into the work. Whoever looked at those figures was thinking of Christ on the cross, but it also recalled much more pressing images of then-current events, images of the war in Afghanistan, where the soldiers’ naked dead bodies were hanged under the bridges. Atrocities still executed by humans, 2000 years after the crucifixion. This was what I wanted to address in the work.

Then, in 2017, I was blown away by the discovery of the ‘Enclosed Gardens.’ They are small cabinets for private devotion built for the rooms of the nuns and filled with an excessive array of silk flowers, relics, and polychrome sculptures of saints. I kept thinking, what could I ‘steal’ from there and translate it to my work, to my world. What was it that made the ‘hortus conclusus’ so valuable, so intriguing to me?

I’m very interested in how the concept of the garden, in a broader sense, relates to the notion of care. What do these cabinets really look like?

They are very intimate: very modest on the outside, with doors that were only opened when one wanted to pray, and wildly excessive on the inside. This hidden world of luscious exuberance was very intriguing to me. Then, of course, there’s all the storytelling that surrounds the sacred imagery, but I was particularly overwhelmed by the flower motifs. Speaking of care, these miniature flowers were meticulously crafted. The Garden of Eden was an important theme for the nuns who lived ‘imprisoned.’ When they entered the convent, as Brides of Christ, they stayed there for life. Since they were nurses, they connected with life outside, but mostly through their patients. The Garden of Eden was their absolute freedom. A window to the world in one way, but also a sublimation of their sexual being, connected to the body of Christ, their husband. It was exhilarating to translate all these ideas into my work.

The figure of the angel as protector, saviour, or healer is central in this exhibition as a tribute to healthcare workers and caregivers. Do you think we could draw a parallel between the angel and the artist — in the sense that the artist can comfort those in need or offer a gateway to a better future?

Yes, I believe this sense of perspective, of possibility, and hope is what we are all looking for. I find it most when surrounded by movies and books. I find comfort in what other people, who share the same reality as I do, have taken in, digested in their unique way, and decided to give back to the world. I suppose this is the artist’s role. Nicolas, it is actually a beautiful metaphor to think of the artist as an angel.

But I am convinced you are an angel!

Let’s not go that far. In any case, it’s a significant compliment when people see me as part of the work — not just as the maker of these sculptures but as an inherent part of the works and what they have to offer.

You mentioned ‘books’ a moment ago, and I admit my obsession with novelist J. M. Coetzee, whom you also greatly admire. If I remember correctly, he curated your exhibition for the Belgian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. I’m just curious about what else is on your reading shelf at the moment.

I’m reading some older books by Dutch author Connie Palmen. From a young age, she wanted to become a writer, and this relentless endeavour is so tangible in her work. I know from my personal experience how tough this struggle can be: I remember how I reluctantly asked my parents if I could go to art school. It was not an obvious choice back then. And that was just the start of it. It’s something we have in common. For me, Palmen’s work can be connected to that of J. M. Coetzee in the sense that the focus is always on the human condition: the suffering, the beauty, and what we learn or fail to learn from life. Palmen lost two husbands; in her work, you can sense the strength to continue and the hope to identify new possibilities. This was eye-opening for me. Reading her books can be truly therapeutic.

Among other philosophers and thinkers, I’m also interested in Philipp Blom, who references the past to discuss the future. In “The Vertigo Years,” he speaks about the period before World War I when there was this widespread feeling that everything was going downhill – quite similar to what we’re living now, right? We both express an inevitable drama in our work, sharing common anxieties and fears…

…and here we have the power of literature. I’m wondering what else fuels you up? I imagine you travel a lot. Which are your favourite destinations?

My husband and I are addicted to India, but traveling in the past years has been problematic due to the safety restrictions. Our trip to Iran in 1996 was extremely inspiring as well; such a remarkable place with rich culture. Back then, it was still very easy to travel there. We were dazzled by a country loaded with traditions and customs passed down from generation to generation. It’s incredible how people there had such deep knowledge about the past. I was impressed that they learned entire poems by heart, and I’m really grateful to have had this experience before things turned sour. It’s heartbreaking to see how such a delicate culture can be brutally violated.

I also travel extensively for work and am currently preparing an exhibition in Rome. I went before Christmas to see the space and explore the city again. I haven’t been there for long, yet it helped me figure out which works could make sense to present. It’s not just about bringing works from my studio to Rome but about creating a connection with the place, its current situation, and its history.

I treasure how our conversation naturally concludes in the Città Eterna. Every time I visit Rome, I have this personal ritual of going straight to La Galleria Nazionale to see your horse sculptures (“We are all Flesh”). You’ve worked with animal skins for most of your career. Last question, do you own a pet?

Yes, we have a dog. We call her Rena, which blends the names of my two sons, René and Andreas. She’s a Malinois Shepherd, and it’s the third one we’ve had in over thirty years. She’s always with us in the studio.

Berlinde De Bruyckere

PHOTO CREDIT

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Berlinde De Bruyckere

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Thomas Dashuber / Diözesanmuseum Freising

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily V, 2018 (detail)

2018

Wood, paper, textile, epoxy, iron, polyurethane, rope

212 x 148 x 40 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt

Berlinde De Bruyckere

Arcangelo (Freising), 2021 – 2022 (detail)

2022

Bronze, lead patina, Belgian limestone, steel

Height: 500 cm

Installation view: Diözesan Museum, Freising

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Thomas Dashuber / Diözesan Museum

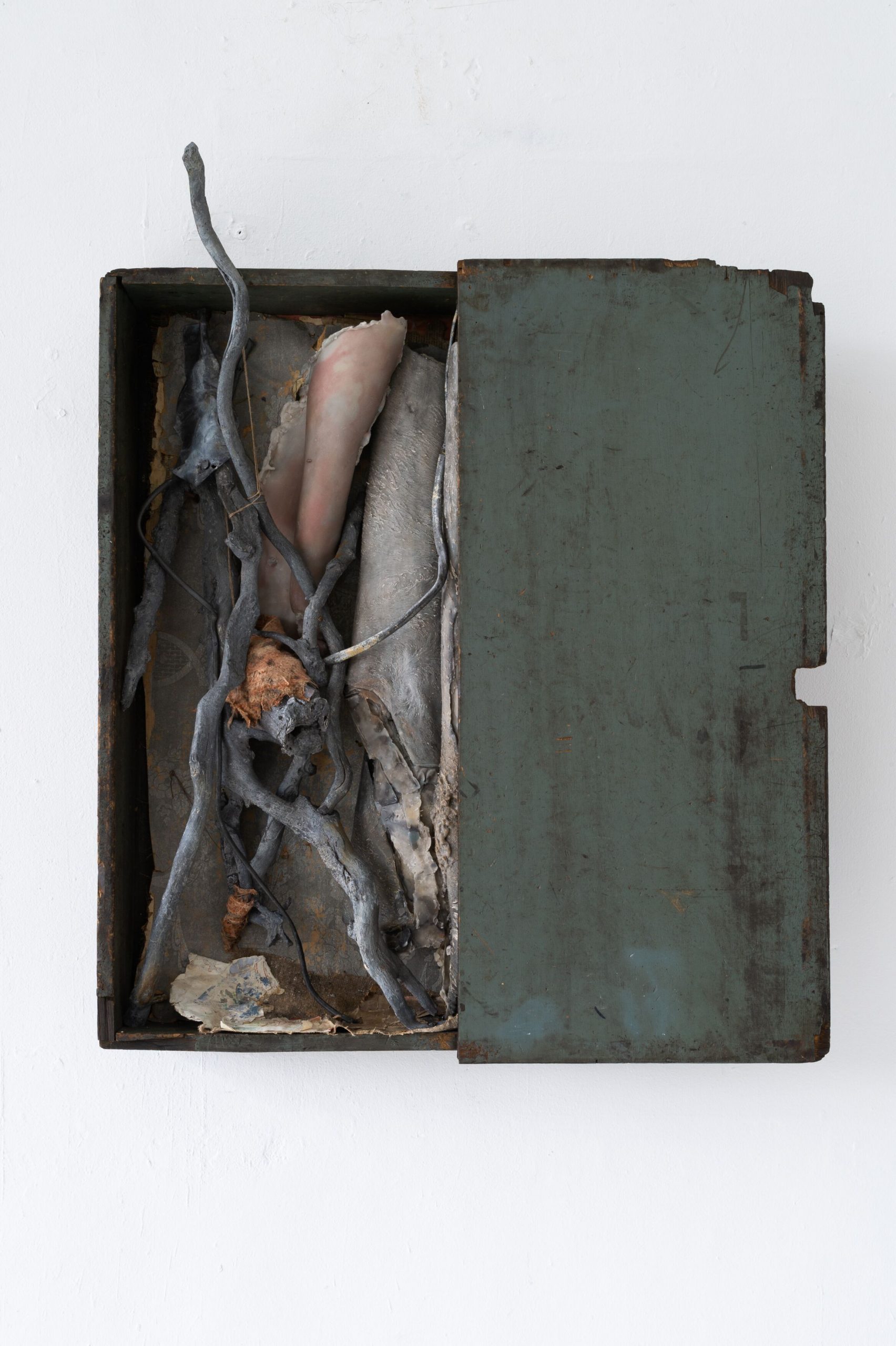

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily, 2021-2023

2023

Wax, lead, wallpaper, textile, wood, rope

102 x 83 x 22 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily, 2019 – 2022

2022

Tracing paper and thread on paper

44,8 x 28 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt

BIO

Born in Ghent in 1964, where she lives and works, Berlinde De Bruyckere is influenced by traditions of the Flemish Renaissance. Drawing from the legacies of the European Old Masters, religious iconography, as well as mythology, and cultural lore, the artist layers existing histories with new narratives to create a psychological terrain of pathos, tenderness, and unease. The vulnerability and fragility of man, the suffering body — both human and animal — and the power of nature are some of her core motifs. Since her first exhibition in the mid-eighties, De Bruyckere’s works have been the subject of numerous exhibitions in major institutions worldwide. In 2013 she represented Belgium at the 55th Venice Biennale.

Berlinde De Bruyckere

PHOTO CREDIT

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Berlinde De Bruyckere

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Thomas Dashuber / Diözesanmuseum Freising

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Installation view: Berlinde De Bruyckere. A simple prophecy

Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, 2023

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily V, 2018 (detail)

2018

Wood, paper, textile, epoxy, iron, polyurethane, rope

212 x 148 x 40 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt

Berlinde De Bruyckere

Arcangelo (Freising), 2021 – 2022 (detail)

2022

Bronze, lead patina, Belgian limestone, steel

Height: 500 cm

Installation view: Diözesan Museum, Freising

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Thomas Dashuber / Diözesan Museum

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily, 2021-2023

2023

Wax, lead, wallpaper, textile, wood, rope

102 x 83 x 22 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt

Berlinde De Bruyckere

It almost seemed a lily, 2019 – 2022

2022

Tracing paper and thread on paper

44,8 x 28 cm

© Berlinde De Bruyckere

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Mirjam Devriendt