Where things happen #29 — Dicembre 2024

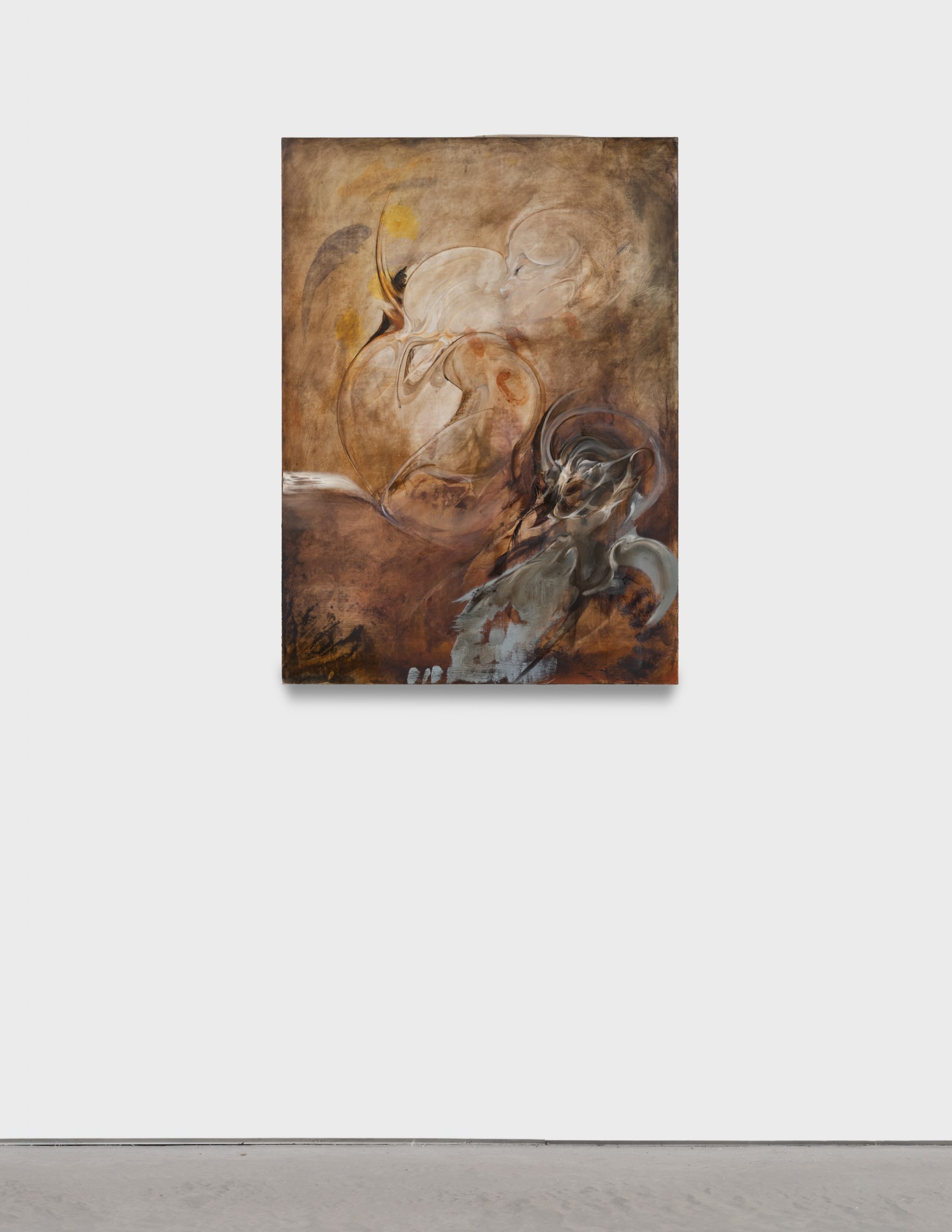

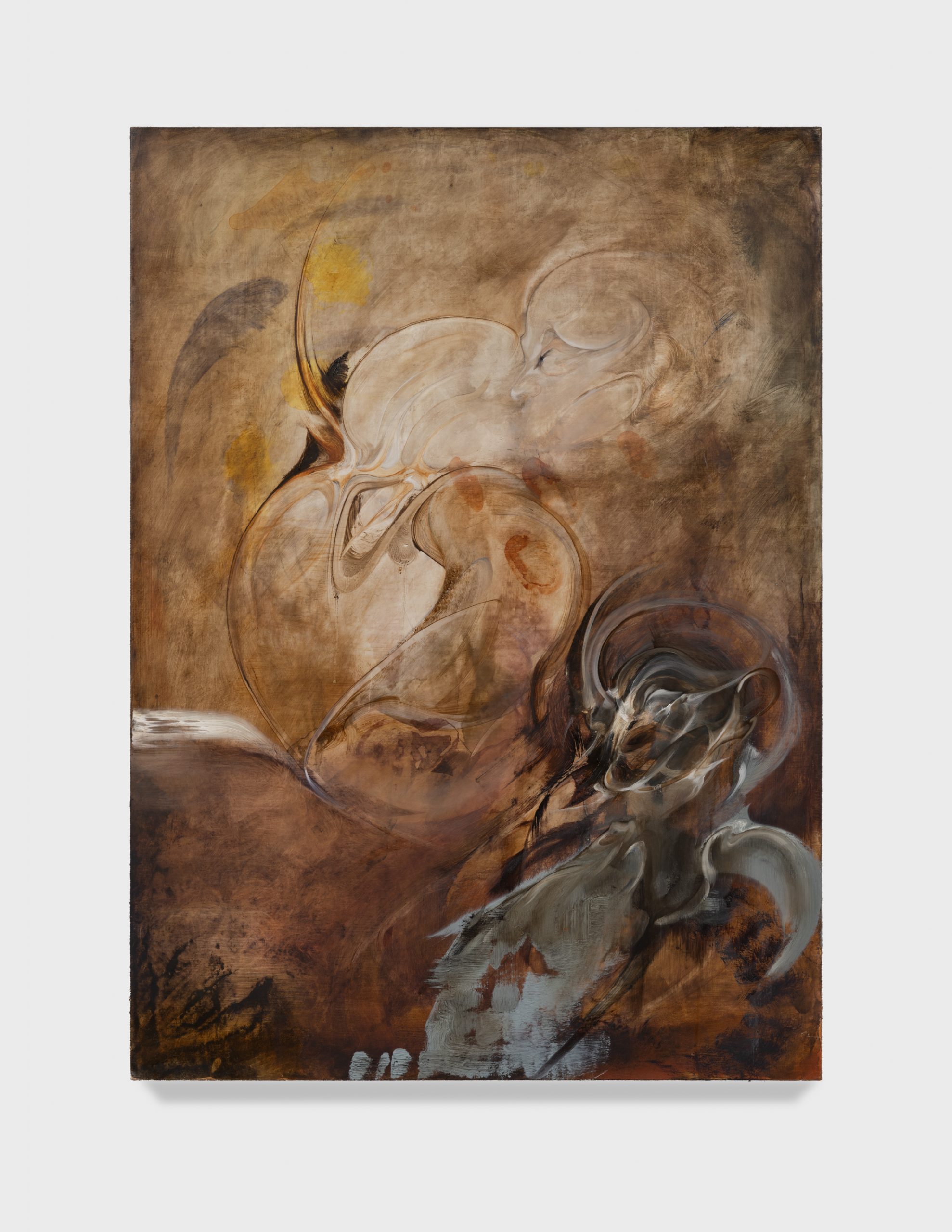

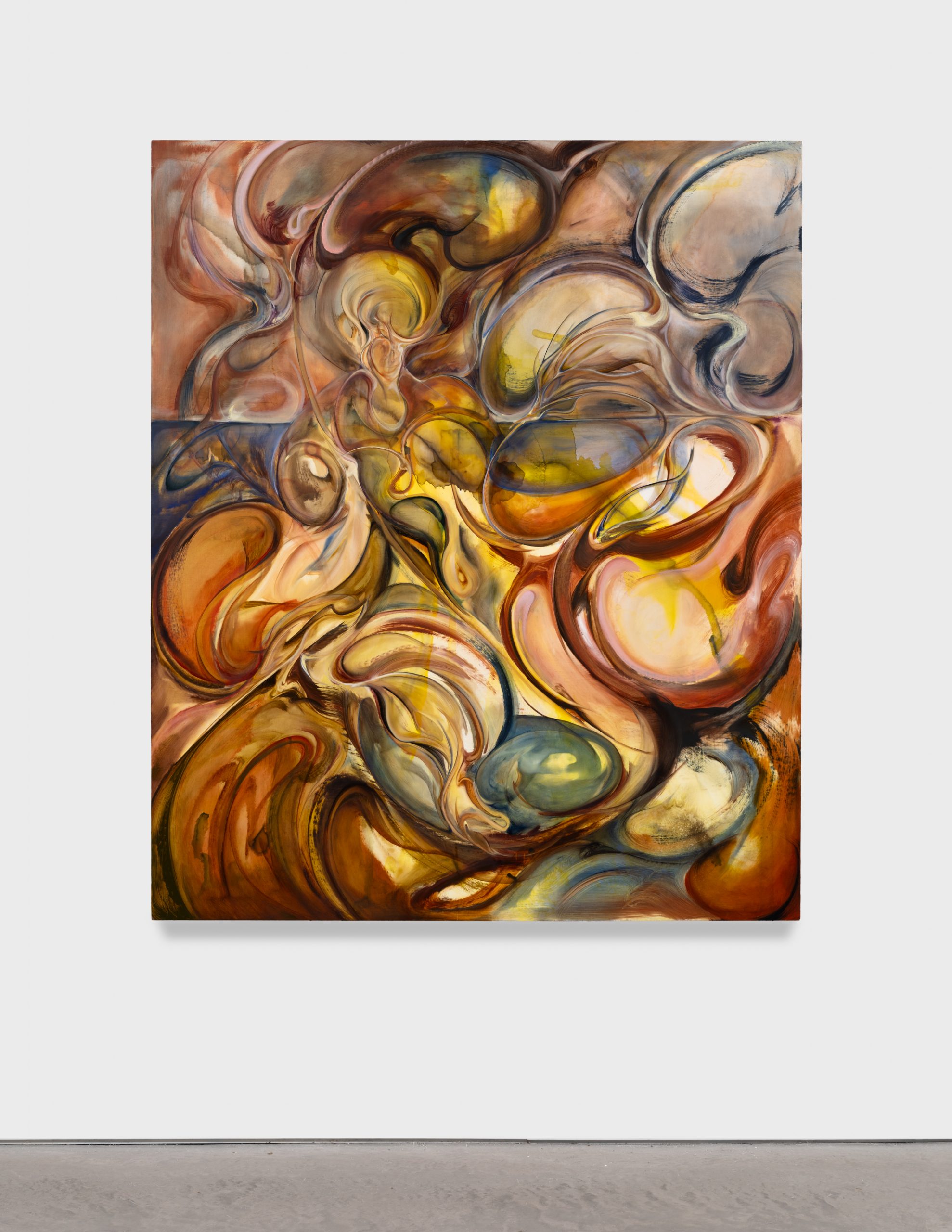

Blair Whiteford’s work lives in this limbo between figuration and abstraction, as his actions on the canvas are directed mainly by psychological energies that move entire painting tides into new possible expressive directions. Freely drawing from art history, Whiterford consistently inserts his work within a flux of references and connections in a continuous conversation with a broad group of artists from the past. “I look at the history of painting a lot,” Whiteford says, “and think about where I want something to sit in the world right now, right? That’s where it all starts.”

When we met the artist in his Bushwick studio, he had just wrapped up a large solo exhibition at Matthew Brown but was already back at work. Two medium canvases were in progress, and a larger one was potentially awaiting new layers.

As Whiteford explains, painting is, first and foremost, an addiction and a need, as we can also understand from the physical and psychological transfer process on canvas.

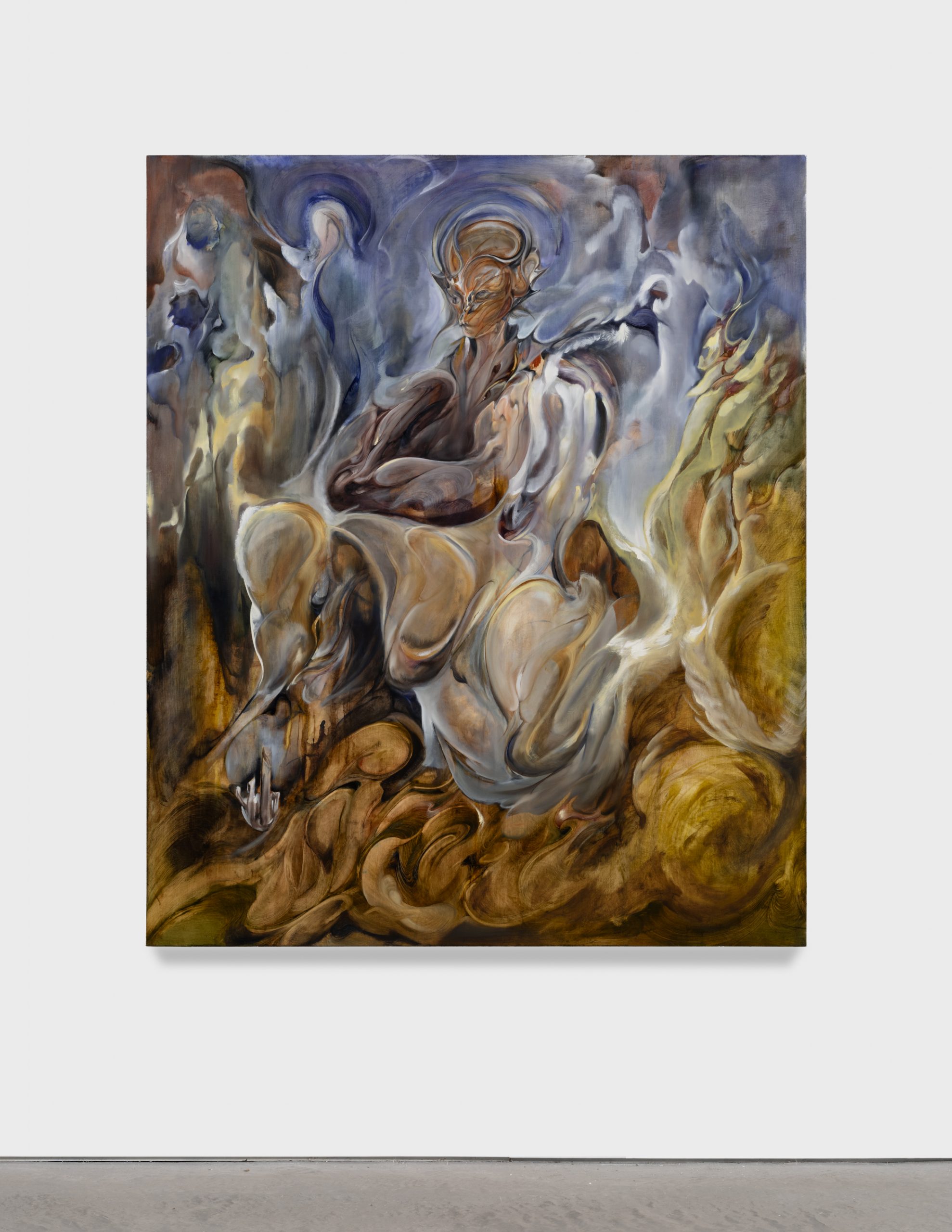

As he explains, his paintings result from an accumulation of layers of structures, most of the time dictated by colors and pigments, that suggest the next linear move. A magmatic swirling yet undefined reality, where all the forces and elements are still present, flows into painterly waves until some human figures slowly emerge, anchoring the entire composition.

The humanoids that appear in Whiteford’s works eventually function as a fulcrum for a series of waves of painterly matter gravitating around them as the vortex finds its center.

Imbued by this primordial energy, the artist’s painterly explorations transform the canvas into a stage for a transcendental experience where landscape, portraiture, and abstraction blend indistinguishably. In this sense, they translate a synchronicity between space, time and being, which allows multiple historical and spatial cultural dimensions to coexist in a flying blending of references.

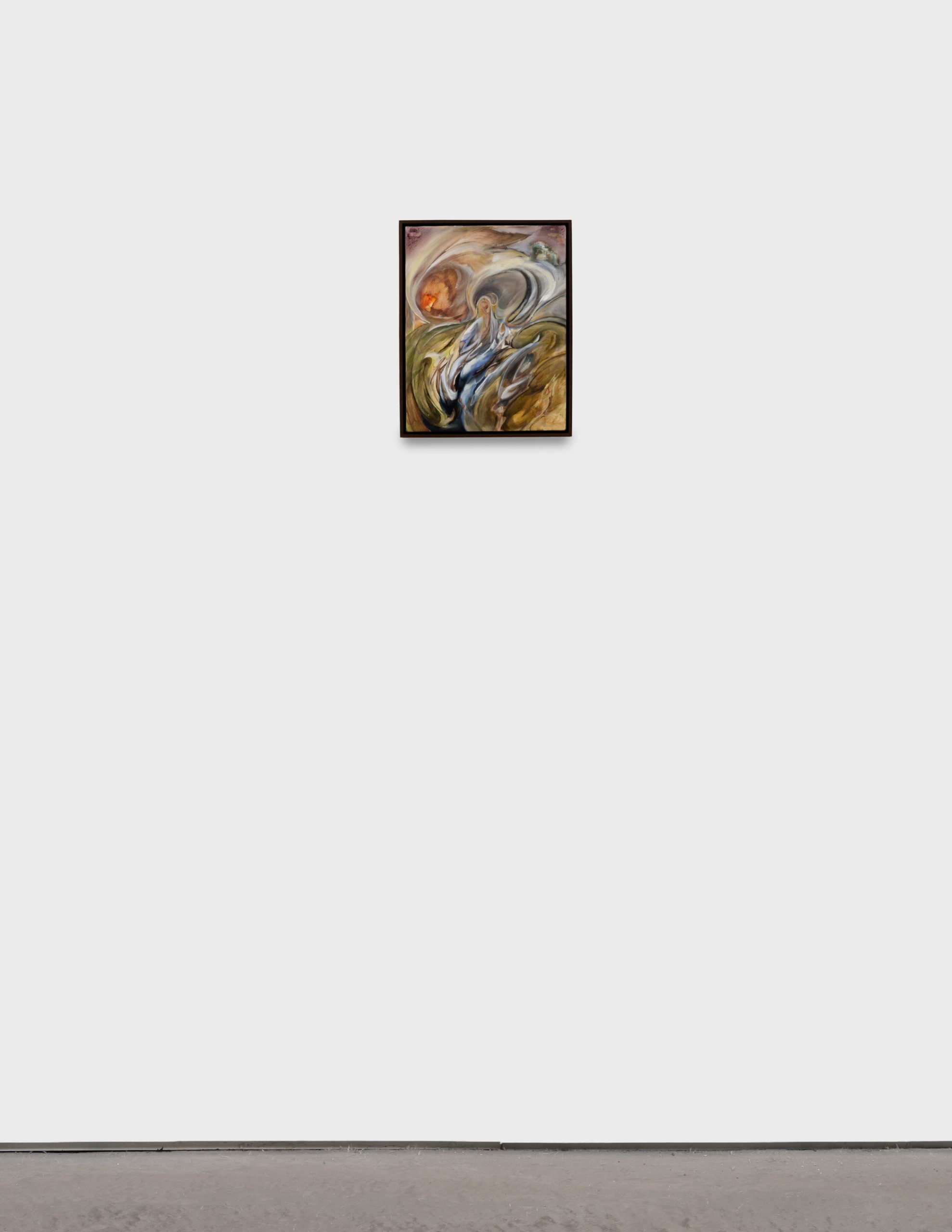

Also, there’s a sort of musicality and rhythm at the heart of Whiteford’s canvases, as the artist always paints with music, as he tells us, and the rhythm somehow influences and dictates the fluid movement through which the canvas will develop. More specifically, Whiteford is interested in the nonverbal aspect of music and how, despite lacking the coded semiotical dimension, it can still evoke specific emotional and psychological atmospheres by touching on more unconscious and automatic responses. Similarly, in his work, Whiteford tries to distill and amplify motions and sensations and translate the multilayered and relative multiperspective nature. From rhythmic aspect that he uses to conduct his movements on the canvas also derives a deep physical engagement from it. Not surprisingly, the artist is much more comfortable with more extensive scales, he says: while the smaller ones become more obsessive and introspective, the larger formats allow a more fluid and spontaneous development of forms in a continuous flux.

In this sense, the artist’s compositions seem to be animated by the notion of “énal vital” elaborated by French Philosopher Henry Bregson to describe the seemingly chaotic restless flow of matter and energy from which everything takes form, a life force based on an essential unity of time, matter, and energy and space that allows a continuous evolution in the existence of all things. Still, this force is not mechanistic, as it does not respond to rules of cause and effect, but it’s a creative principle fueled by universal energies based on a mysterious cosmic order.

Also, for this reason, Whiteford’s paintings often seem to express a similar level of turmoil and existential drama that artists like El Greco or Van Gogh translated in their tumultuous and agitated brushstrokes and most often originate from the tension between a desire for transcendency and the perceived limits of the physical and sensory human world. As in El Greco’s works, Whiteford also explores this dimension in between heaven and earth, the condemnation to a purgatory condition and dimension from which humans can elevate themselves just if they tap into a deeper essence of reality, rediscovering the inherent pure beauty, order and fertile creative generation of the universal unity between all elements. As Whiteford’s painting action proceeds, an internal ordering emerges from the formless chaos, shaping compositions that live in a liminal fertile dimension between physical reality and the oneiric world.

Embracing an intuitive development of canvas in an absolute surrender to what the universe, the colors and the situation suggest, the artist’s work dives into a collective unconscious of archetypes and formal structures of symmetry and composition that are shared universally by elevated minds. Whiteford, however, mostly denies his associations with Surrealism and instead feels himself close to Cubism, as he’s interested in how they built and translated the complex structure of reality through fragmentation. Picasso is his main inspiration and favorite artist, he confesses. Still, Whiteford wants to insert more emphasized dynamics in this discourse, similar to what futurism or Orphism explored, to respond better and translate the extreme dynamics that characterize our reality.

As we discuss, we can understand how fluidity and lightning are the two main poles between the entire practice of Whiteford moves around – contended between a spontaneous, fluid emanation of forms and a more dramatic staging. As evoking the miracle of creation, painting is the source of his imaginative power of turning a potentially convulsed nothing into some new forms. However, as Blair Whiteford clarifies, his paintings are still anchored in physical reality and his own experience and memories with nature. In this sense, we can see how Whiteford’s entangled systems of forms and colors eventually combine and result in unity, as the artist tried to represent this complicated yet lively system of interconnections happening collectively around us and from which all existences depend.

Most recently, Whiteford has been struggling with the existence of images: how to create visuals that can still have relevance and tenure can be challenging, amidst the endless flow of media and how to make them enter the ongoing evolution of painting and image creations, where symbols, forms and archetypes constantly remerge.

Eventually, we can describe Whiteford’s work as deeply driven by this desire to make something that people can see and relate to immediately—to create canvases that touch on universal topics that can be understood across cultures.

“I would like to make something that people can see and relate to immediately, and maybe they can share some of my feelings about what it feels like to be a person right now and how that has become really complicated,”he says in a closing note.