Where things happen #23— May 2024

This month we change city for our reportage and we get to Chicago, another vibrant and growing hub for contemporary art, as its art week this April just proved.

With a strong presence of local institutions and art schools and a growing number of contemporary galleries opening in the windy city coupled with a committed midwestern art audience, Chicago presents today a fertile territory for a community of artists who want to avoid the economical and competition pressure of cities as New York and Los Angeles.

Here we met with Chris Bradley, an incredibly resourceful artist whose practice brilliantly combines playfulness and craftsmanship, while pursuing a critical commentary of habits of consumption of products and experiences in contemporary society.

With his hyper realistic sculptures, Bradley works around the ordinary and mundane material presences that surround our daily life – everything that most often becomes such a commonplace that we are unable to notice their aesthetic, physiological and narrative properties.

In entering his studio, it’s impossible not to be amazed by the number of tools and machines proving how the artist is able to move so swiftly between medium and techniques, from bronze to wood, with this extreme mastery and awareness of materials.

Bradley’s studio is located in a warehouse in west town, Chicago. As we step in – in addition to his lovely dog, and some nice breakfast snacks – we are welcomed by a tower made of pretzel sticks, attached together with chewing gum.

Or better, a perfect imitation of this.

This version of the sculpture is quite tall, and appears to bear some references to Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, a utopian structure aiming for the sky, both precarious and audacious in its engineering but exalting in this way the advanced inventiveness of the society that produced it.

As I think of this reference, I start to understand the type of irony that animates all of Bradley’s practice, as he plays with some of the most beloved products and symbols of American consumer culture and society.

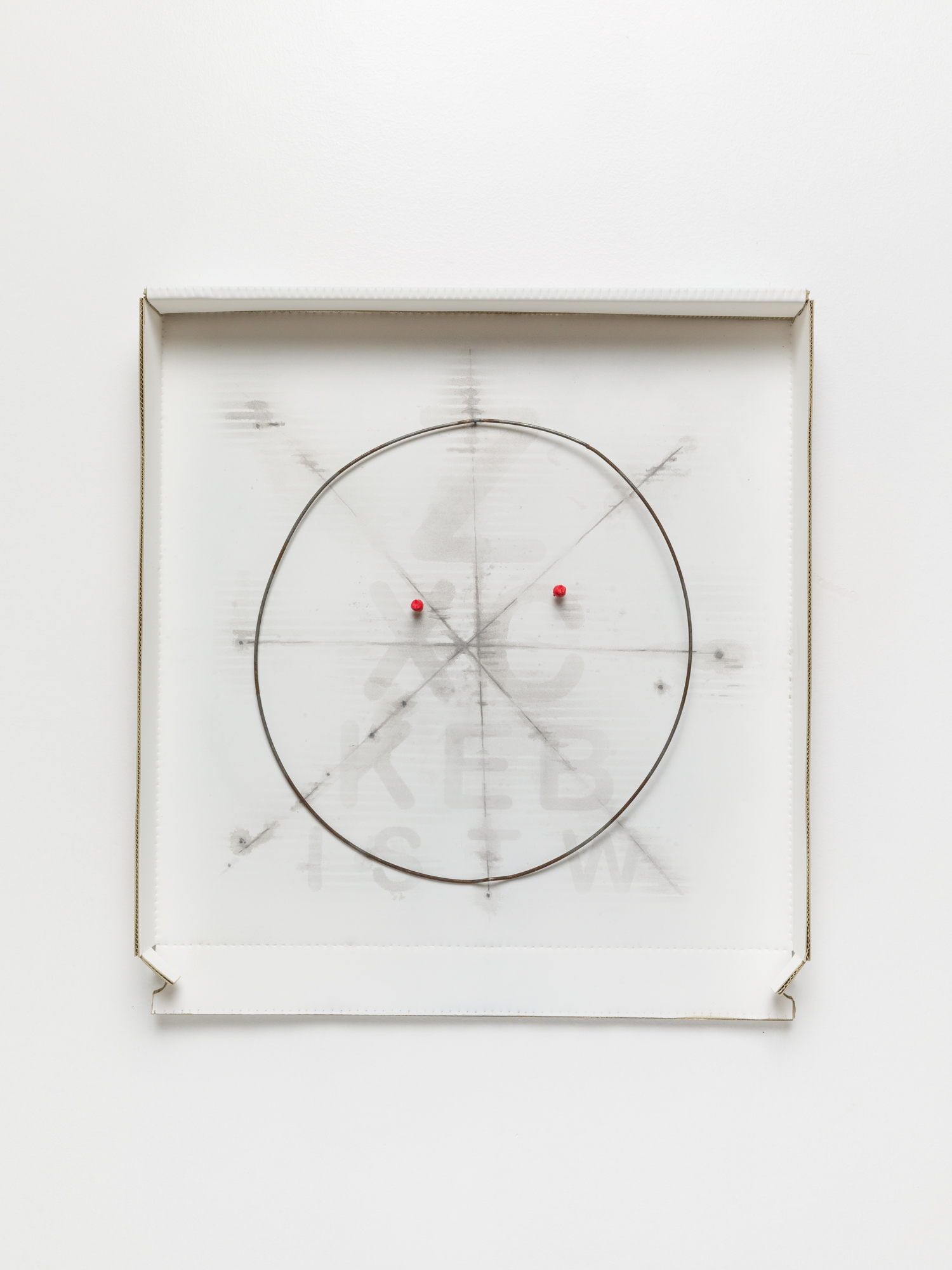

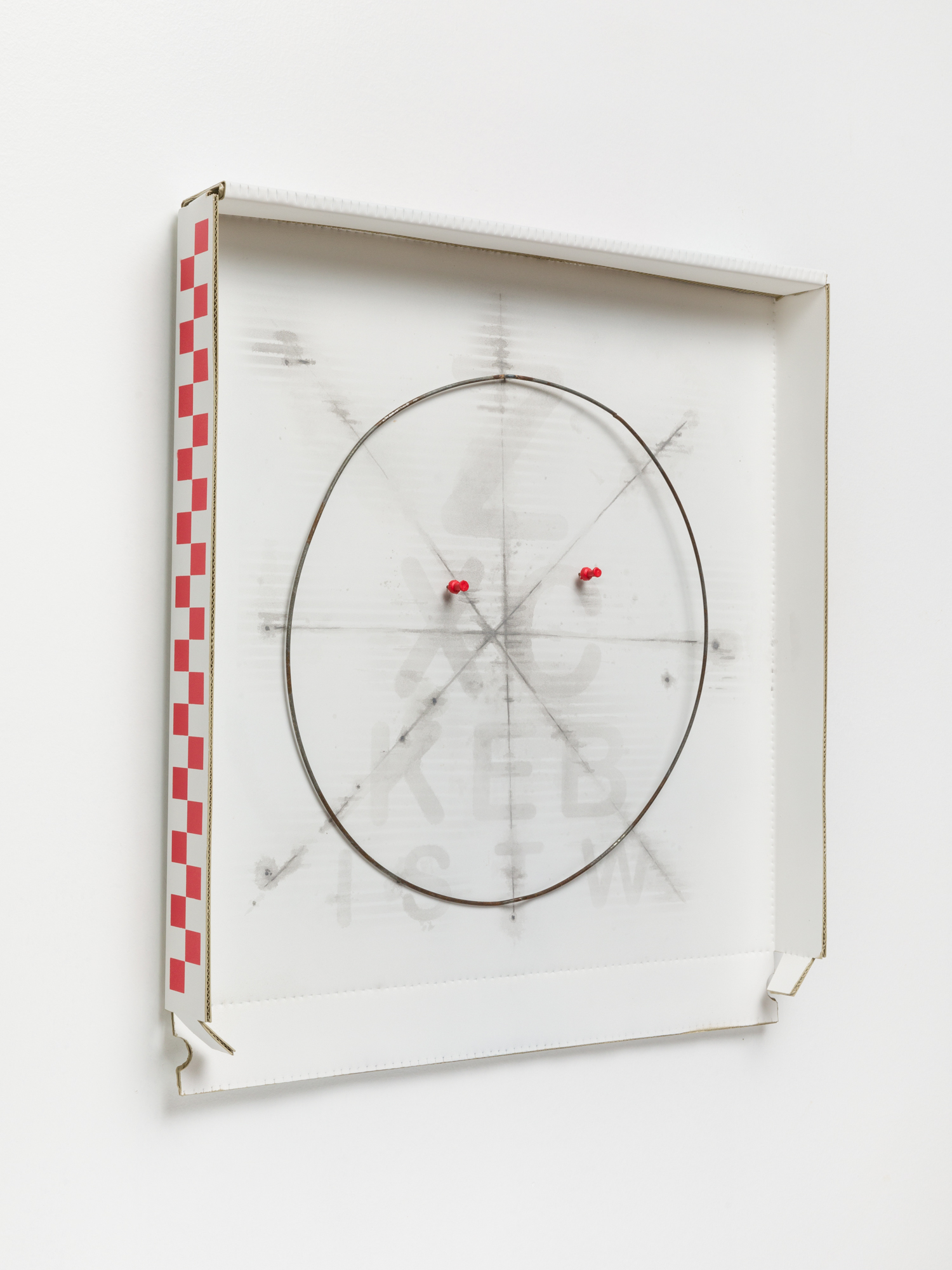

Around the studio, we can see some empty boxes of pizza, also made of bronze. Some of these works are meant to go on the wall, others imitate even the dirt of oil, turning the pizza box in a surface for unexpected greasy portraits.

Hanging on another wall, some bread lofts made of soft material.

Bradley’s sculptures can be described as some sort of trompe l’oeil, or trick for the eyes: their meticulous fine craftsmanship allows the bronze to assume a more soft and tempting quality of food, while wood convincingly takes on qualities of metal or plastic. His art is a mirror to reality, with a delusively crafty impulse added to it.

As the different range of works emulating objects in his studio reveals, Chris Bradley‘a endless inventiveness is always coupled with humor.

His jovial smile also seems a recurrent feature, as he clearly approaches the surrounding reality with a similar level of acceptance, critical investigation, and sarcasm that his work suggests.

The more one sees of his work and listens him explaining, it becomes clear how Bradley’s art is informed by the same notion of ironeia as once described by Socrates, Plato and Aristotle: drawing from the greek verb εἴρων meaning “questioning”, irony means a voluntary simulation which eventually allows a critical speculation, a methodic doubt, or a suspension of disbelief that, in admitting to don’t know, allow to access another knowledge and awareness of reality.

Nevertheless, behind the colorful playfulness, Bradley’s critical attitude seems to resonate more with the “practical pessimists” that Nietzsche associated with “irony”, the one that allows one to accept the material world as it is, bearing an awareness of the inexorable obsolescence and finitude everything is subjected to.

Bradley’s attempt to emulate the mundane reality, the objects and products that surround our everyday life, can be read as an attempt to immolate them as timeless totemic presences, and at the same time momentum mori of their finitude.

Eventually, all these works are not different from the vanitas we find in old masters and Flemish paintings in particular, functioning as reminders of the ephemerality and caducity of each material and terrestrial pleasure.

Once one enters in such a philosophical and aesthetical territory, it’s easier also articulate in a better way on the relation between Bradley’s practice and pop art, and with Warhol in particular.

As Andy Warhol, Bradley embraces a similar notation of accessible art that directly draws its modes from the American mass production/distribution, but also applying the Duchampian strategy of ready made to work on copies/alter egos of the “real thing”.

However, in doing so, Bradley reinvents ready-made and appropriation in a way that get his art closer to Cleas Oldenbourg’s artistic operations, keeping the artistry and excellence in making an exact replica, as imitation of reality – something that also the most traditional notion of art instructs, from Plato to Renaissance.

With Warhol Bradley still seems to share this very sharp mockery of middle-class common taste fabricated by the media, with their perverse voyeuristic fascinations for others people’s grief as entertainment, and with the ephemerality of its idols and values, most often reduced into superficial pictures so easily consumed, but quickly falling into obsolescence.

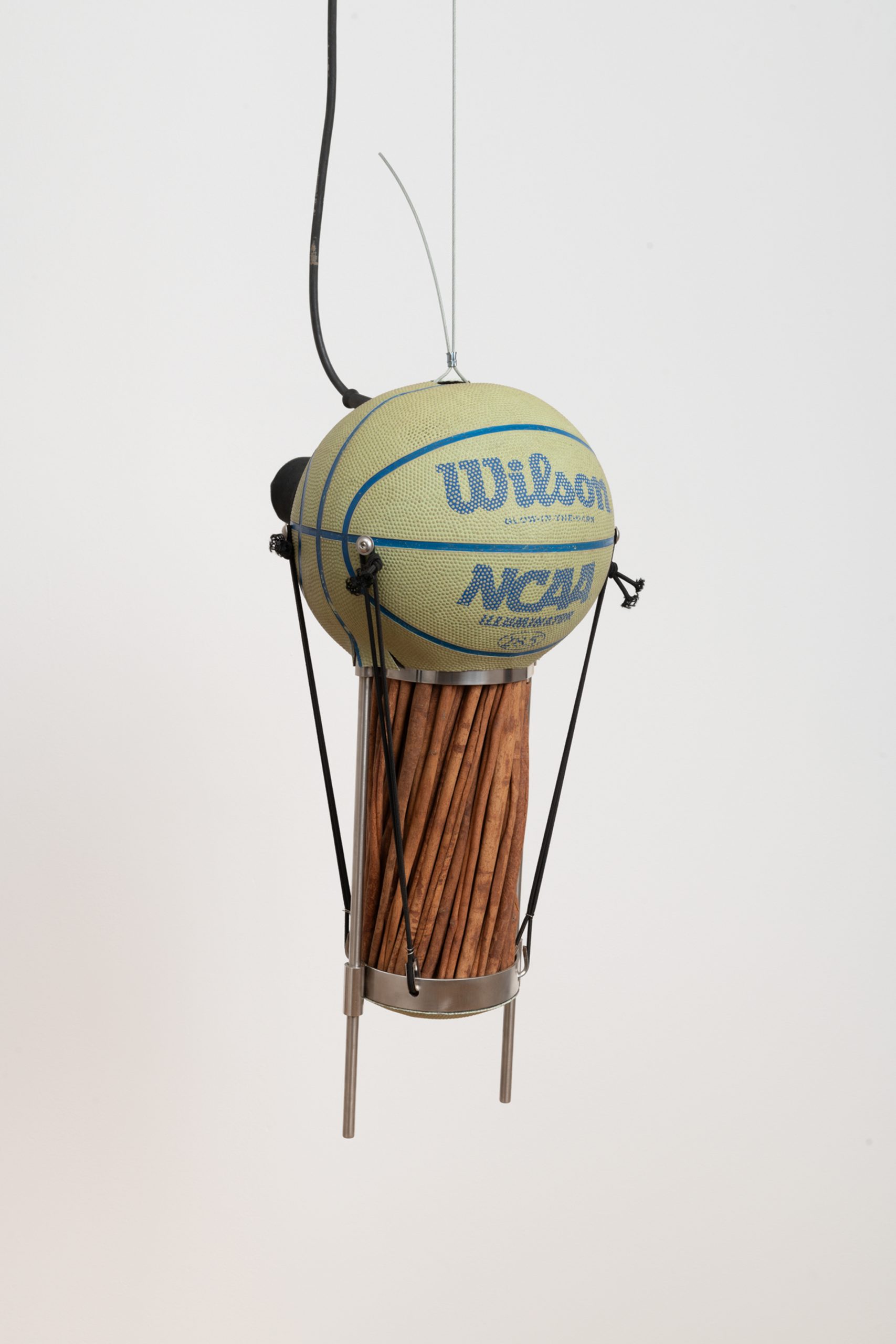

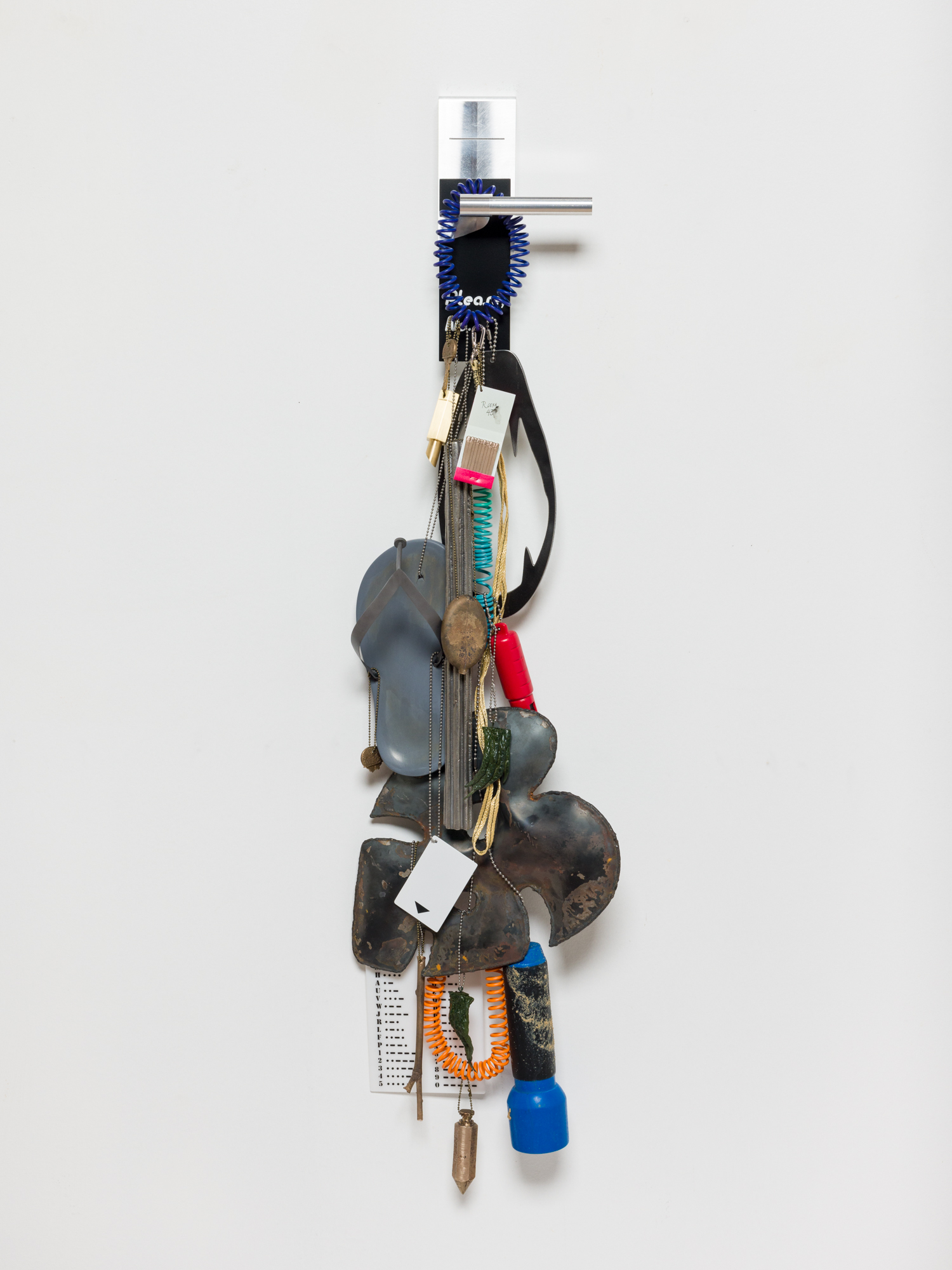

Behind these references, however, there’s something more slippery, in Bradley practice, especially when the works turn into kinetic: the apparently purposeless movement of a potato on the wall or the no sense of a basketball with cinnamon grounding cinnamon, are paradoxical, and inherently “weird” presences in the space which are more in line with the Surrealist assemblages: casual encounters between objects that turn them into unexpected and uncanny characters, staging a material situation that subverts any cultural linguistic expectation for that specific objects or products, as they’ve been already transported by the artist to another dimension of perception.

As observed in the essay accompanying his recent show at MCA Chicago, Bradley’s sculptures are charged with what the father of surrealism Andre Breton would call “associative and interpretive qualities,” which go unnoticed until they are activated by the viewer’s desire.

It must be for this that some of his work, either completed or in progress, often gives the idea of tools for physics experiments and demonstrations.

Appropriating and mirroring the mundane but injecting some surreal weirdness to it, Chris Bradley encourages both faith and disbelief in all the material presences and phenomena around us, and the codes and rules we use to interpret them.

This can be read also as somehow similar to what Joseph Konsuth did with his One and Three Chairs: an operation of meta representation forces us to look at this system of objects and language closer, and accept the inherent relativity within.

As Plato once formulated, there’s the idea, the archetype, then the object, then a commonly accepted word or concept codifying it, in this precise order of reality we live in.

However, we often forget how this is just a possible perspective, a possible formulation and translation of it only based on our linguistic and sensory capabilities, which could be different for other entities.

Bradley’s work can therefore be described also conceptual art, as Kosuth defined “based on an inquiry into the nature of art” “Fundamental to this idea of art is the understanding of the linguistic nature of all art propositions, be they past or present, and regardless of the elements used in their construction”.

In his morphing, imitating and then shifting objects, Bradley undertook a tireless contestation of the established boundaries between object making and art making, between functional and creative, between fiction and reality, to prove the intrinsic relative nature of these categorizations.

Eventually, through his fine craftsmanship and extreme knowledge of materials, Bradley has succeeded to create his own epistemological and ontological system to test everyday reality, and reveal the mechanisms of an endless circle of capitalist consumption and disgregation.

Chris Bradley fully embraces and creates with his work what the philosopher Michel Foucault would call heterotopias: worlds within worlds, mirroring and yet upsetting what is outside.

Disturbing, uncanny, paradoxical, contradictory or transforming the everyday, Bradley’s sculptures prompt the viewer to a similar operation of interrogation and distrust which eventually reveals the critical potential of non ordinariness lying beneath what we describe as reality.

In this way, Bradley’s work encourages to simply embrace the only perspective that seems possible of “emplacement”, understanding the material world as a “site” of action and expression, only produced through human sense-making.