Where things happen #17— September 2023

When one explores deeper today’s society in South Korea, they will begin to understand how the country lives in a situation of ideological, identity, and cultural tensions between a millenary culture, a persistent conservatism and patriarchalism and culture heavily committed to work, stemming both from a strong presence of Protestantism, Catholicism and Buddishm at the same time. All of these issues are now clashing with the idols of Kpop and Kmovie celebrities, who become aspirational models for the new generations, partially representing freer lifestyle, while embodying specific biopolitics that still rule on an ideal of perfection.

The result is therefore a strong social pressure, especially geared towards younger generations. In this context, Dew Kim’s practice offers an unfiltered analysis of the contrasts and distortions that exist in both Korean society and popular culture today.

This deep reading of the situation Kim is able to archive, is also partially due to his own particular, personal background: being his father’s only child, a Presbyterian pastor in one of Seoul’s lesser income neighborhoods. Dew grew up surrounded by Christian literature and lessons, but as a shy, lonely child; Dew often fantasized about biblical stories and discovered sides of them that relate to broader human behaviors and inclinations.

I met with Dew first at his studio in New York a month ago, while he was in residency at ISCP in Brooklyn. This wasn’t the first time in the US for him: several years ago his father had sent him to a tiny town called Goshen in Indiana, one of the most conservative states in the country. A place where American consumerism and advertising morosely meets and mixes with religious extremism. The result manifests into icon fueled capitalism and strange billboards that lead you either to paradise, or hell. Dew began to study English there, but he felt a similar pressure as in Korea in a community of Mennonites, who shared the same rigid approach to religion, and life, as the environment where he was raised.

After some time, he started to escape to Chicago on weekends.Then he finally moved to NYC, where he began meeting like minded people and explored more freely and fully the uncharted imaginative realms of pleasure, and art. After this period of self discovery and liberation, Dew moved to London to pursue his MA in Sculpture from Royal College of Art.

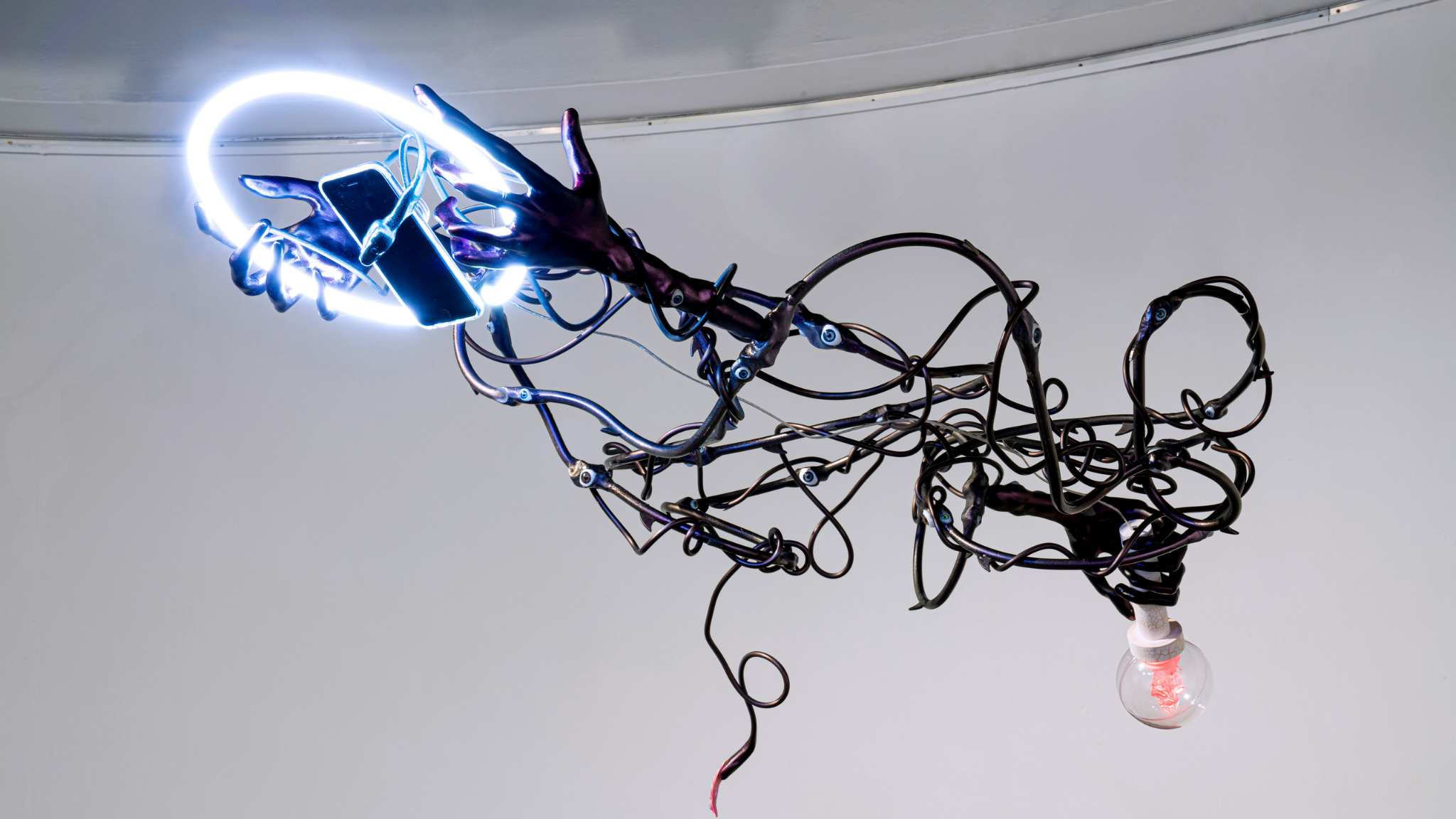

It comes with nor surprise, looking at his work, that this was actually preceded by a BFA in Metalsmithing and Jewelry from Konkuk University: this peculiar combination in educational backgrounds allows Dew Kim a special approach to sculpture, that results in extremely refined metal structures enriched by sophisticated multimedia elements or surfaces and details that reconnect them to the body. In this way, the creation of objects becomes more performative, as the work represents the body in one form or another.

Being at once extremely sensual and carnal, and likewise austere, cold and polished, Dew Kim’s sculptures inhabit this existential limbo between sacral objects, tools of pleasure and instruments of torture. A tension between danger and beauty, pleasure and suffering, that largely informs also the artist’s practice and narrative.

Making an effort to further contextualize Dew Kim’s practice into the specific landscape of Korean culture and society, it’s interesting to note one of the most important factors leading to widespread acceptance of Christianity: at the time, this conversion became part of the resistance to the Japanese systematic campaign of cultural assimilation, Many Christians were therefore forged mostly with the cause of Korean nationalism, as a resistance to the Japanese occupation.

However, as it often happens, religions share many key values that prove how they were, since the beginning, a tool to educate and instruct people. In particular, this allowed an enduring legacy of heteropatriarchal values and disciplinary mechanisms imposed with the colonial and authoritarian periods, resulting in a heavy sense of duty and of sacrifice that resonated also with the corporate society that shaped Korea’s economic excellence today.

In this context, we can read Dew Kim’s work as a form of both escapism, criticism and resistance. Purveying some of the extremes of sexual pleasure, imagination and art, Dew Kim found a unique space of experimentation for a form of contemporary art which can be finally liberated from the societal contractions, and therefore reflect more in depth what are the desires, and the emotional and psychological struggles of a generation. When we met the second time during Seoul art week, Dew Kim had just moved back to South Korea.

On an early Sunday morning before the art fair he welcomed us at his studio in Itaewon, a once-low-income neighborhood that has turned into a hip spot over the last years (proven by the piles of empty liquor bottles on the street), thanks to the many gay bars in the area.

In fact, despite the apparent progressiveness and development of the country, South Korea is one of the countries in Asia which still considers homosexuality illegal. When we would later go for a coffee in a Turkish cafè, I would be surprised to discover Itaewon also hosts Seoul’s Muslim community – a coexistence that is extremely unique in the world, but forced by the fact that both are critical minorities in the country.

Although there has undoubtedly been an increase in awareness and acknowledgement of queer people in the country, there are still many push backs for a wider acceptance: in 2007, under pressure from conservative Christian groups, the Ministry of Justice removed ‘sexual orientation’ from the Korean Human Rights Bill, effectively decriminalizing on the basis of sexuality. More conservative Christian groups even claim homosexuality as a threat to national security, and the “Korean cultural integrity”.

In this context, Dew Kim is one of the few South Korean artists who fearlessly embraces and presents an expressively queer aesthetic and narrative, making him an important spokesperson for the entire community. This often results in an aesthetic made exaggeration and disguise up to the grotesque or uncanny, which he adopted as subversive tools to challenge the the status quo, but also as intentional reminder of the body’s mutability and instability of hierarchical and gender categories resulted from today’s technological advancements.

At the particular moment Kim didn’t have much in the studio, as he just embarked on the epilogue of his Kpop saga, which will concentrate on the idea of a future Apocalypse for idols. His new multimedia series will present a final phase of a K-pop idols performance: combining the divine and bizarre it will be the climax and closure of his study on sadomasochistic representations in popular culture, but it will also result in an unveiling metaphor of the ending fairytales of all the religious dogmas that long prevented a free expression of the inner self.

In challenging the existing conservative norms, especially in his videos and performances, Dew Kim also adopts BDSM aspects, diving into a deeper psychological and sociological analysis that mysteriously combining sacredness, masochism and eroticism, eventually unveils how similar dynamics exist both on religious and cultural idols.

Many of Dew Kim’s works inherently deal also with desire, and in particular an unfulfilled one, which is then sublimated or exorcised in his creations. This desire, however, appears to extend well beyond a sexual and relational one, touching on a deeper sense of incompleteness, of longing for meaningful human connections and experiences, which is shared by many in the new generation.

Andrew Cummings, in the book Imagining the Apocalypse: Art and the End Times (2022) has described how Dew’s work ‘invite[s] us to take pleasure in porosity’. The highly technological and futuristic aspect that characterizes both Kim’s video and sculptures, in fact, also reveal an interesting commentary on the modified interaction between the development of gender, sexuality, and technology. Particularly the artist confesses his interest in how the development of technology has extended gender exploration to a faster and more diverse perspective, which extends his research also to post-humanity and trans-humanism: the new digital and cyber allow a new fluid space for transformative post gender narratives to develop.

Worth to note how, historically, the rejection of homosexuality in South Korea eventually seem to originate also from an ideal of a perfect and sanitized body that has become a key aspiration model in Korean society, as proven by the obsession with cosmetics and plastic surgery, now widely used in the country across genders and ages. Once again, this phenomenon can be attributed to the Japanese colonization which resulted in an imposition also of specific knowledge concerning the body, gender norms, and hygiene that promoted the idea of a ‘perfectly functional physical body’, modeled on ideals of (white) masculinity, heterosexuality, and health. In this sense, Kim’s work significantly challenges both the traditional and current models implied by bio-politics in Korea, encouraging to embrace a more fluid and multifaceted expression of the self, which seems to better resonate what the new generations would need and claim.

Eventually, the imaginative realms explored by Dew Kim with his multimedia works seems to poem a powerful utopian scenario for an important ideological change, which will finally envisions alternative possibilities of conceiving of the body and social relations, beyond fixed categories of gender, desire, and human relations.