Edoardo Manzoni

Jenaury 2025

The thirteenth edition of the Francesco Fabbri Prize for Contemporary Arts this year saw Edoardo Manzoni as the winner of the Emerging Art section.

In this interview we discussed some of the themes that his practice addresses such as deception, seduction and the dynamics of subjugation in a parallel between ancestral rituals such as hunting and our contemporary world where competition for the gaze and attention makes us all prey.

Taverna (Fioritura) is the work that won you the Fabbri Prize in the Emerging Art section. It is an aluminium sculpture that reproduces a bundle of branches without the wooden texture that they should have. For centuries it has been the hand of man that has imitated the textures of nature; in your work it is nature that absorbs the forms and surfaces produced by man in a reverse scheumorphism. How did this work come about? What does the title refer to?

I found this bundle of branches in a deserted place, I immediately noticed them because they were very smooth, I don’t know if they were wood polished by someone to make sticks, or if they were worked by the current of a river.

The idea (and in general that of the ‘Fioritura’ series, of which this work is a part) is to start with dry branches, elements that have completed their previous life cycle, to melt them in metal, to fix them in time, and to give them a new body. The wood, once cast in aluminium, is transformed from a natural element into a cold and artificial display, a kind of theatre that stages stylised and coloured forms as if they were inflorescences, hence the title of the series, which evokes the idea of rebirth. The title of the work, on the other hand, comes from the fact that, in order to draw the coloured silhouettes, I was inspired by the wall of an old tavern, on which you can find a little bit of everything: food, vegetables, tools and furniture. These shapes are based on elements of reality, but they are definitely abstract. They try to evoke images without directly representing anything, suggesting an ornamental and purely human nature.

Traps and their mechanism of seduction and deception and the practice of hunting and trapping are elements that characterise several of your works. What is the meeting point between these ancestral rituals, such as hunting, and contemporaneity in your opinion?

Much of my work explores the ancestral relationship between humans and non-humans, and hunting plays a key role in this. The animal was our first mirror, driven by hunger we learned to imitate it in order to hunt it, and in hunting it we separated ourselves from it.

Seduction, in the negative sense of misleading, of bringing the other to one’s side by deception, is one of the most effective predatory strategies. An example of this is the ‘lark’s mirror’, a trap that gave rise to the an Italian famous saying and inspired a series of my works. This instrument consisted of rotating paddles on which small mirrors were placed. The birds, attracted by the light reflected by the mirrors, would fall into the net prepared by the hunters. Decontextualised from its ordinary function, I worked on the form of the lark to shift the focus to its cultural implications. If today hunting is no longer understood as a primary means of survival, the imagery associated with it does not cease to preserve and bear witness to a complex network of dynamics that spill over into society and the systems of which we are part. Where, in a logic of domination, there is always something or someone that is reduced to prey or object of capture.

In your latest exhibition, Inchino at Galleria Renata Fabbri in Milan, you present sculptural works that explore ornamentation as a meeting point between human aesthetics and the animal world. Both man-made traps and the ornamentation of animal fur and plumage are presented as instruments of capture, of the attention of the sexual partner in one case, and of capture tout court in the other. Are these aesthetic pitfalls meant to warn the viewer?

I am interested in suggesting that the artist is not so different from a hunter or an illusionist, who creates works as traps to lure the viewer. Even in my works, if on the one hand we have the violent seduction of the trap, the law of the fight where the strongest wins, on the other hand we have the loving seduction where the sense of beauty wins. This is the case with the birds of paradise that I presented as sculptures in that exhibition.

In my exhibitions, the hunt, as well as the choreographies of courtship that I stage, seem crystallised, static, everything always on the verge of taking shape, one step away from its outcome. My traps disguise themselves as works of art, they are clearly visible, they do not blend in with the environment, they lose their function as ‘bait’ and look more like huge jewels made of poor materials. By removing the idea of bait, I try to blur the line between sculpture, trap and ornament. The aim is to create a tension between the object and the viewer through feelings of attraction, seduction and repulsion.

Do you have any exhibitions in the pipeline? What are you working on at the moment?

In the last period, I have created several works, always starting with themes related to seduction, but shifting the focus to, for example, the relationship between flowers and insects. Now I am back in a research phase rather than a production phase, I am interested in many other issues that I would like to explore, I would like to take my work into new forms and directions.

PHOTO CREDITS

Edoardo Manzoni, Taverna (Fioritura), 2024, aluminium cast, painted aluminium, Courtesy the artist and Fondazione Francesco Fabbri. Ph. credit Matteo Viti.

Edoardo Manzoni, Allodoliere, 2022, wood, mdf, lacquering, Courtesy the artist and Galleria Lunetta11.

Edoardo Manzoni, Paradiso Minore, 2023, wood, synthetic hair, ropes, paper, installation view, Renata Fabbri, Milano. Ph. credit Mattia Mognetti.

Edoardo Manzoni, Sei Fiori, 2023, wood, steel, dried flowers, installation view, Renata Fabbri, Milano. Ph. credit Mattia Mognetti.

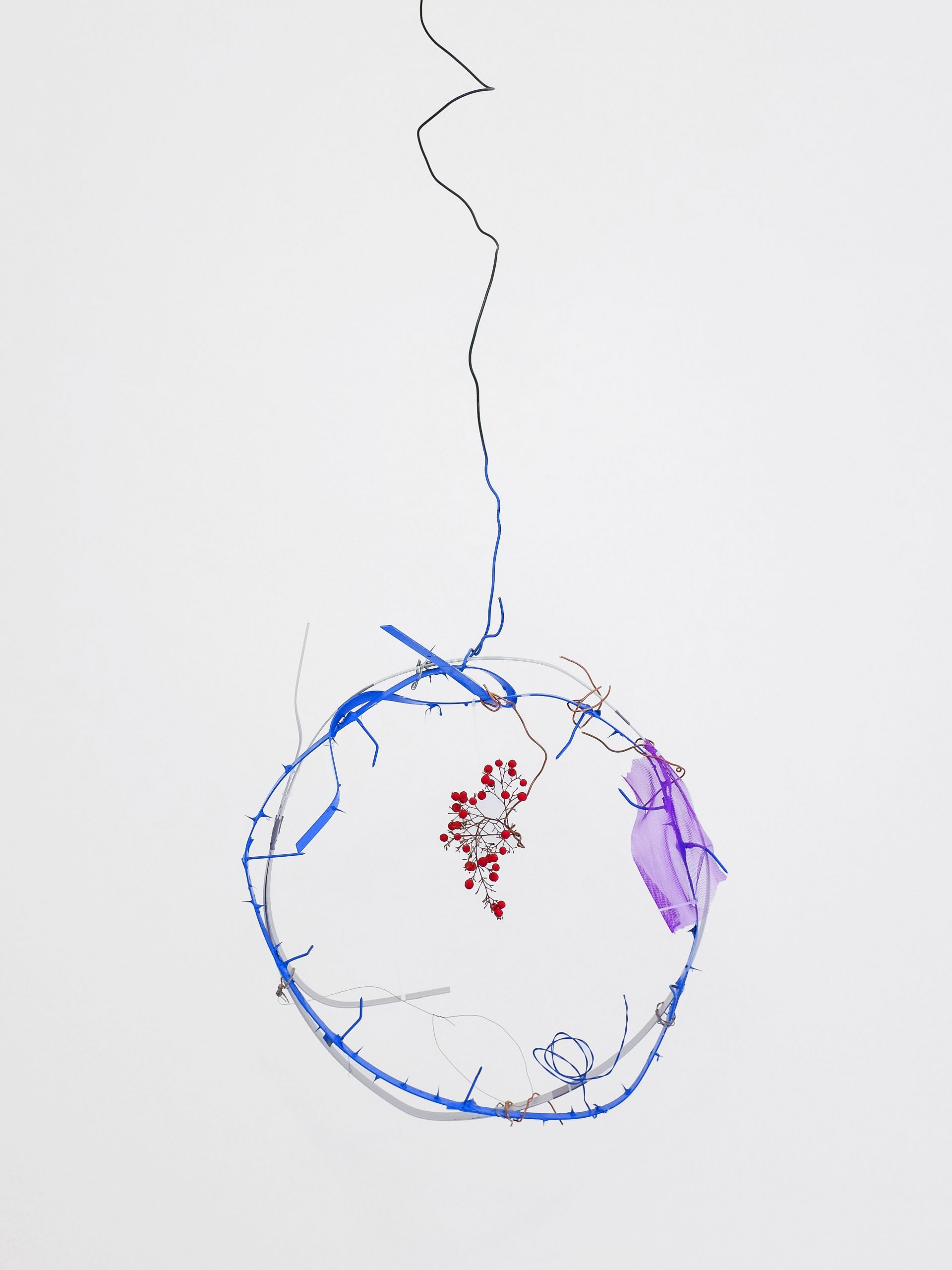

Edoardo Manzoni, Senza titolo (Fame), 2022, iron wire, copper wire, pins, nails, adhesive tape, spray paint, berries, installation view, Galleria Ramo, Como.