Interviews from the ‘PRESENT IS THE NEW FUTURE’ open call

The boundary between different materials is a recurring theme in your research. Yours is a vision where objects and people are surfaces of exchange on which messages pass and are transported, but which at the same time conceal and hide the depth of things. Looking at your works, it always seems that you resort to technology to penetrate and translate these “membranes”, but how do the new technologies relate to this almost anthropological approach of yours to everything that surrounds you?

I refer to sound as a “new technology” because I believe that, like the visual arts, it is a profound anthropological tool. Just think of its applications in ethnomusicology in the 19th century and the subsequent integration of the study of noise within the discipline. However, I am beginning to believe that talking about “new technologies” is now anachronistic and that this expression implies a medial subordination of synthesised sound. Instead, I think that, like a visual document, the sound document is capable of bringing out otherwise hidden levels of the sensible. It amplifies through electricity further forms of interactions, exchanges and surrender of self. Technology is an existence like our own with which we have over time established an exchange of signs; so why not consider it a surface of exchange in turn? It is one of the nervous systems of our life as well as being the last energy to which we entrust the forced hope of prolonging the moment of existence in our final hours.

An example of how technological tools can constitute a further surface of exchange is the site-specific installation Tre canti, realised for the TORRSO space, during the initiatives held for Pesaro Capital of Culture 2024. The work is a sound generated through programming that investigates the limits of language in relation to a second body. Just like the dialogue between two oscillators fixed at opposite poles of the room, we place ourselves in relation with the sensible and dialogue with it, aware that, in that moment of exchange, our signs and our language escape us, dispersing into a hermetically witnessed space, which is all we have left. The listener, called to gradually access the installation via a lift, finds himself wandering in this third space of dialogue, saturated with sound. The intention was to restore the sensation of being inside a microwave oven, an environment in which the body interacted with sound through its own movement. The perception of the sine waves varied according to the listener’s position in the space, making the experience different each time.

Along with technological instruments, it is sound that takes on a fundamental centrality in your work. Sampling, distortions, can you tell us about your creative process and where does this need come from?

I’ve always had a difficult relationship with music: I would start to study an instrument and, despite having positive results in learning it, I would end up abandoning it. I remember playing the pianola we had at home as a child and I never forgot the default sample of that model. Recently I accidentally listened to it again in a Clairo mix on NTS and, moving, I realised that I had never really stopped my relationship with sound, even when I stopped dedicating myself to music in the academic sense.

For a long time I thought I did not have enough experience in a specific field, when in fact I just needed to not identify what I was doing with a specific medium. I started consciously working on and with sound when I realised that in sculpture I could not achieve the sensations I was looking for in the relationship with the material. I then wondered how I could perceive materiality through other channels.

MUTE was one of my first exclusively sound works: an LP produced by Galleria Alessio Moitre in Turin and commissioned by architect Chiara Finizza. It consists of five soundscapes collected through an urban drift in Venice, then dismembered and recomposed. This research allowed me to understand sound as an element capable of cutting through reality like a blade, of deconstructing the norm of toponymy and allowing listening to build new paths, freeing the landscape from its predetermined fruition.

Since then, I have increasingly explored the possibility of establishing a link with reality through performance, a language that has allowed me (and continues to allow me) to actively dialogue with this dimension of sound. It is as if I could enter directly into the loophole of perception and memories to generate and experience new fragments, which emerge at the very moment when the sound practice takes place.

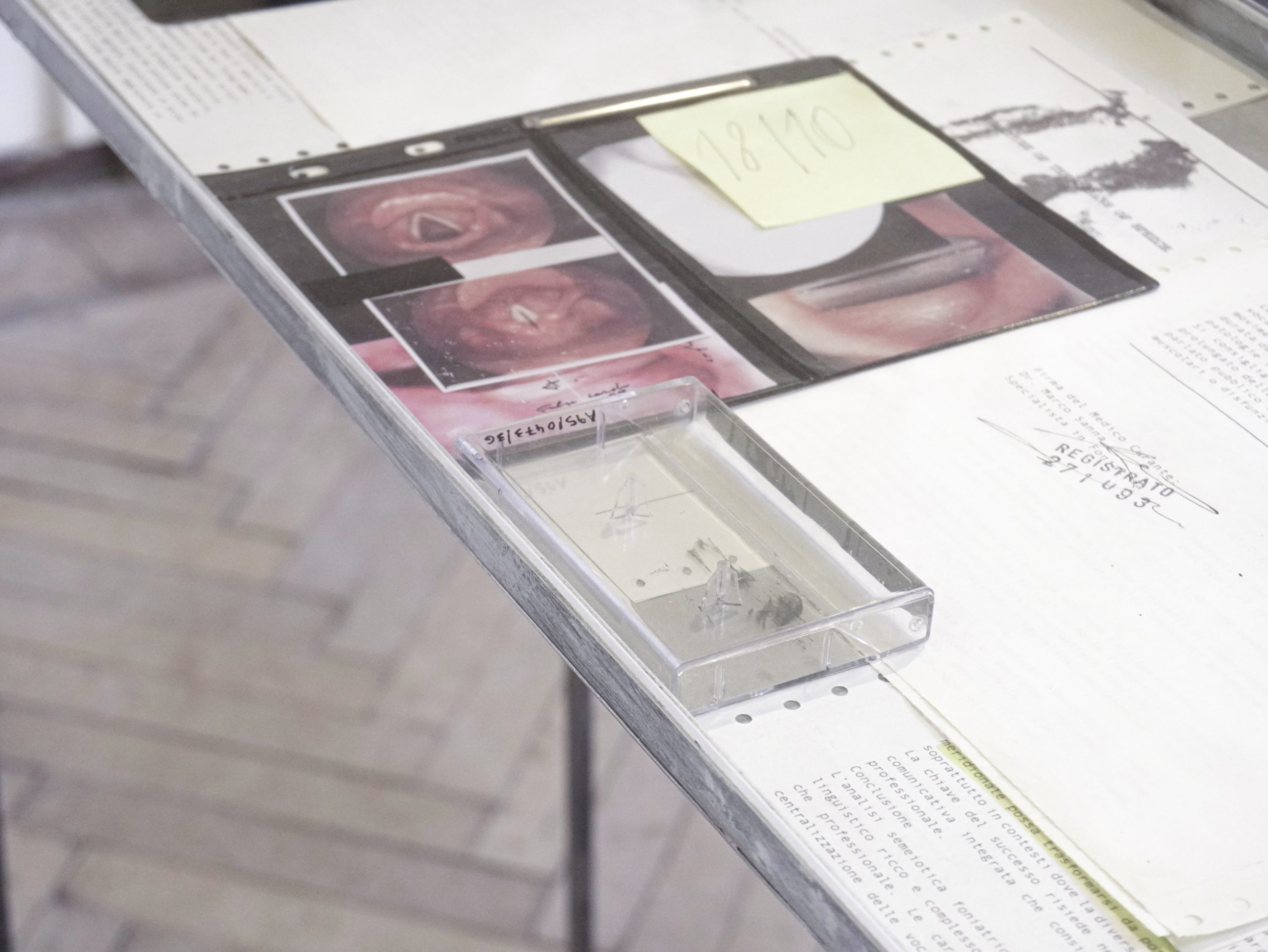

The semi-modular synthesiser I use helps me in this process: it allows me to build a new background for these fragments and to further explore the perceptual potential of sound. Moreover, this material has helped me reconnect with my origins and the Calabrian tradition, after having distanced myself from it due to an internalised anti-meridionalism following my move to northern Italy. It has become an instrument of personal and political analysis, in which listening takes on an active social role. I have explored this aspect in my latest work, fix it till you make it, exhibited at Palazzetto Tito, inside the Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa in Venice. The installation provocatively uses scientific fiction to bring to light those latent and discriminatory traits that, through an aural selection, exclude southern accents from institutional environments, posing a further reflection on diction as a form of forced correction of the body.

In works such as Le jour des saints innocents or Sento l’amaro pianto, you combine liturgical and traditional elements with electronic sounds. What is the significance of this dialogue between the sacred and the contemporary in your artistic practice?

The sacred is closely linked to rituality, a space that leads the person participating in a festival, a mass, a collective event to the loss of the individual self in order to merge into the community. Sound and rhythm have always been central to the ritual dimension of everyday life, the reaping of grain, the olive harvest, the grape harvest, rituals that I have also shared since I was a child. Collective rituals have always had an important place in my growing up, as has the transmission of them in song. I do nothing more than reiterate this transmission and these rituals through what are now the instruments I use, as in Seminati, a composition that links the repetition of the sacred chant to the blessing of the sowing, of my home village, to the concepts of iteration. The sacred context as in Sento l’amaro pianto and the profane are linked in dedicated days in which disguise plays a central role. Immedesimation, theatricality are means by which people identify with historical and sacred subjects in a popular festival and the “sacred thrill” of it.

The electronic sounds in this case are therefore a way of participating again in this intoxication with instruments that are not peculiar to sacred reality, but whose sonic result comes to evoke the same characteristics in the listener. In Le jour des saints innocents with the artist Irene Mathilda Alaimo, we precisely reflected on the exchange of spaces and the role of play as a suspension of the interdicts in the dimension of exchange, where the sacred samplings ended up mingling with the electronic ones, in many cases imagined as distant from them.

What are your future projects? Do you have any exhibitions in the pipeline?

I think I will certainly continue to work with sound and listening in the future, integrating different mediums as usual. I confess that I am looking forward to devoting more time to some residencies so that I can work in situ on the themes that we discussed earlier. There are some exhibitions underway such as the duo exhibition OVER GREEN at the Museo delle Arti di Carrara (mudaC) curated by Elena Perugi, the group exhibition Overlapping Heads in Venice curated by Filippo Maggia, and a multi-site exhibition entitled Esse Potest: compresenze impossibili between Brescia and Cremona.

PHOTO CREDITS

Le jour des saints innocents, performance at PASE PLATFORM, 2024, ph. credits Matteo Giardiello

Fix it till you make it, installation view at Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa, 2025

Tre canti, performance at spazio TORRSO, 2024, ph. credits Marco Augusto Basso

MUTE, LP disk, 2023