Where things happen #26— August 2024

We met Ho Jae on a stuffy Saturday in late August, with a sky over Brooklyn uncertain if it would rain or hold on to all the humidity. Originally from South Korea, Ho Jae has already spent a few years in New York, working as an artist while actively involved in supporting other BIPOC emerging artists’ voices with his organization, “Civil Art.”

The artist’s studio was supposedly empty, from what he initially said, as he had just sent out an entire solo show to Seoul and to his show that had just opened in the Hamptons. Nevertheless, as we enter, we see that there are still four paintings on the wall, all in progress.

Ho Jae’s studio is in a classical brick house in Brooklyn, which the study has converted into his studio, office, gathering place and home.

The artist’s rigorous and intensely professional approach to his practice made him separate at one point his “office” from the place he paints. As we will soon learn, those two separate rooms also represent two distinct phases of his art-making process: the conception of the image and its transfer and translation to canvas. It’s work in the office that Ho Jae reveals to us the intricate process that guides him through his fascinating and highly enigmatic paintings.

As he explains to us once we sit down, his distinctive visual language originates first from his deep fascination for the ethereal perfection of the art of early Renaissance painter Piero Della Francesca. As Ho Jae tells us, being both an artist and a mathematician, Della Francesca perfectly calculated the space in its paintings; everything is positioned in a perfect balance and with a calibrated distance from the other elements to create both a sense of spatial depth and physical, tangible reality, while simultaneously elevating it to another order of cosmic and classical perfection that made his paintings so mysterious and timeless.

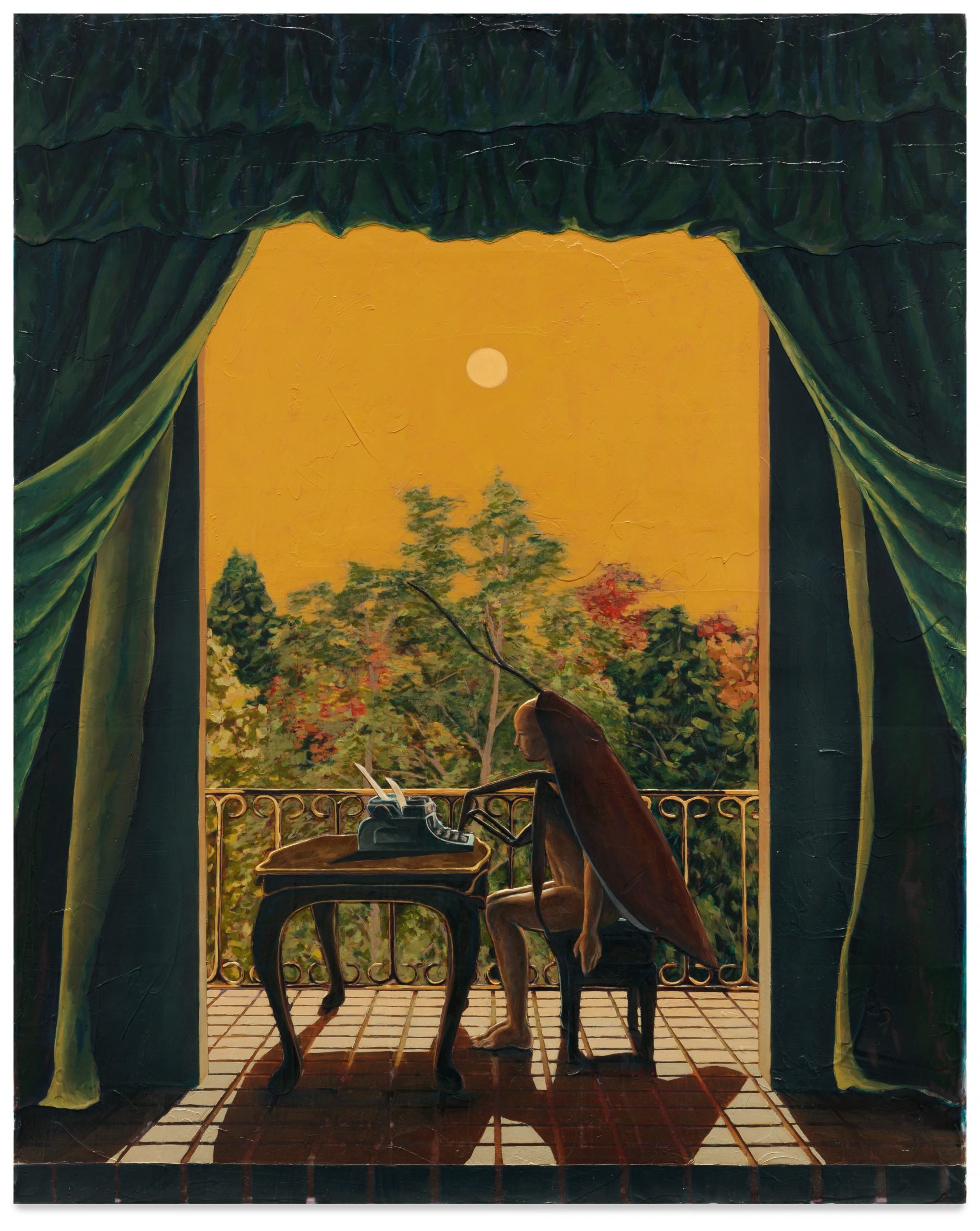

Trying to obtain the same perfection in managing the space, while not being very good in math, Ho Jae found in the possibilities offered by the new technology and digital rendering a way to study at the maximum perfection the space and compositions which will later be applied to his paintings. This passage through software also allows him to study the chromatic and light sensations he wants to convey and the subsequent psychological status while providing this pixelated effect, which the artist then translates on canvas with this nebulous and nuanced effect, heavy on the dramatic use of lights and shadows. This also explains how Ho Jae Kim’s paintings appear to exist in this limbo, between time and space, memory and fantasy, and melancholia and serendipity.

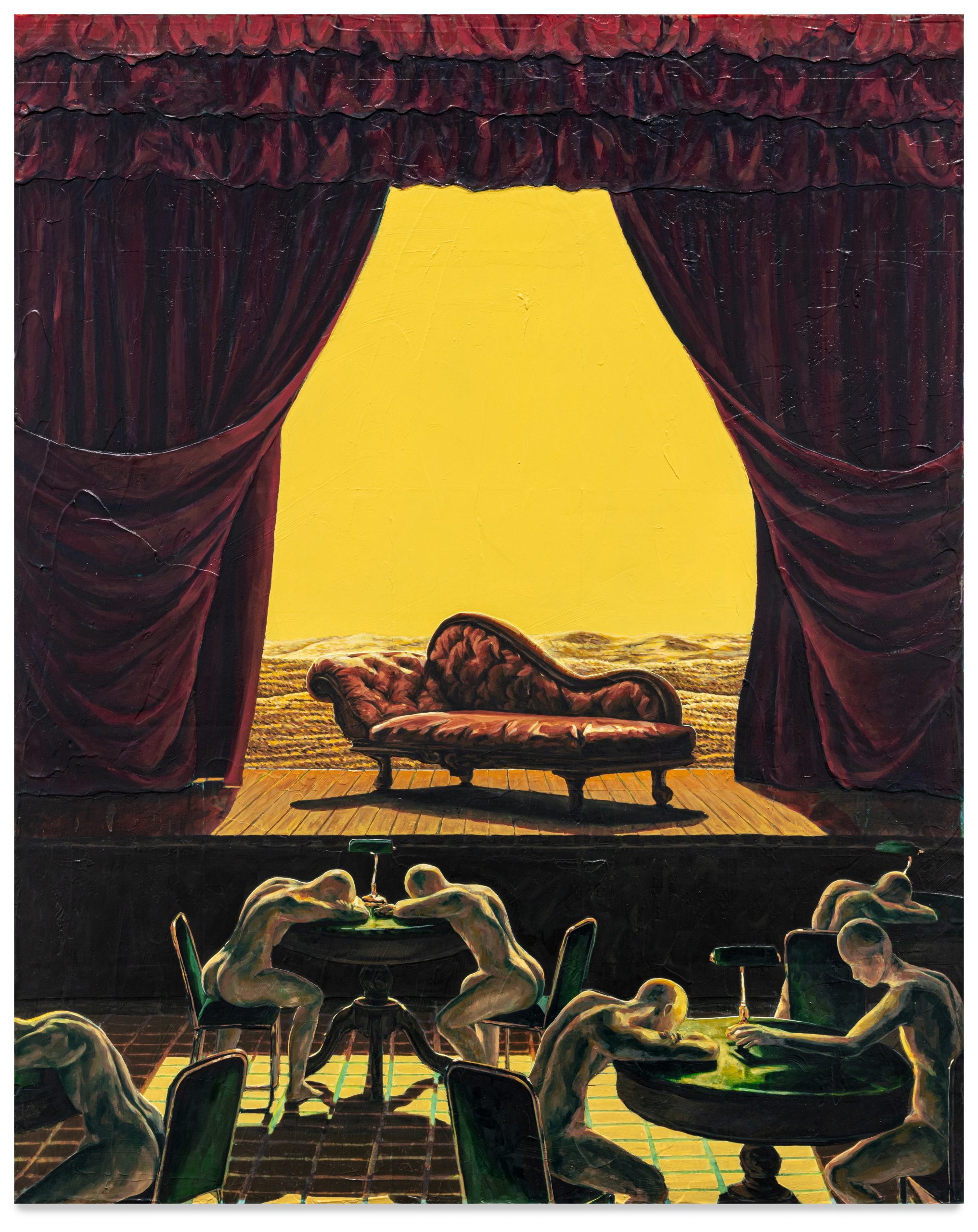

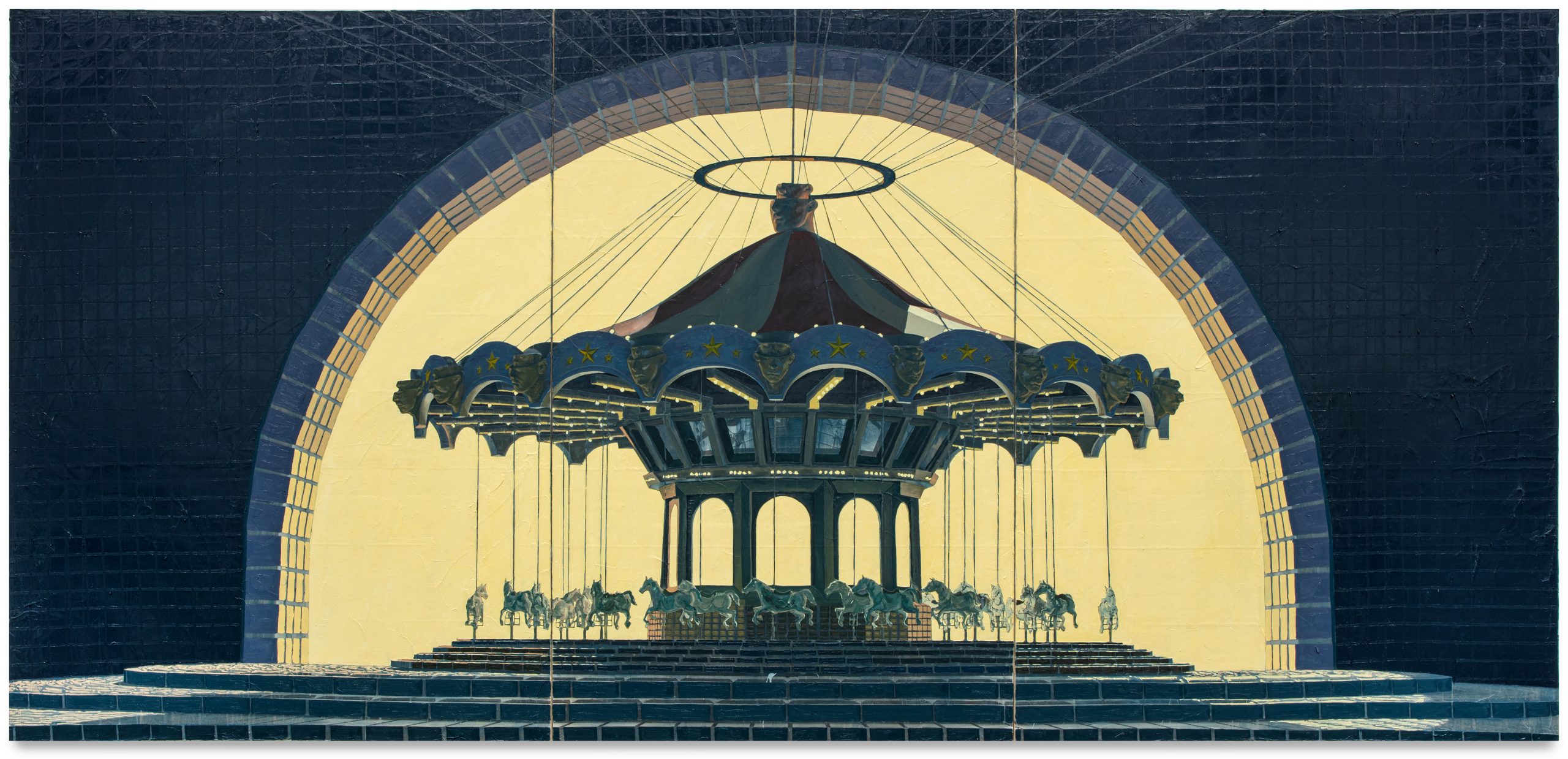

Due to this process, Ho Jae Kim’s work is also characterized by this cinematic quality, which suspends his scene in time and space through a dramatic use of lights and atmosphere. The images that the artist depicts are attentively staged scenes, which, however, cater to something from both the artists’ subconscious and the collective one, They represent intense inner vision, which preserves some universality as images open to reading when interacting with different personal and cultural backgrounds. Ho Jae Kim’s approach to image, in fact, more or less intentionally taps deeper into universal archetypes, recurring when men attempt to give a visual representation of the human condition. Kim carefully presents a series of symbolic presences and mysterious visual clues in his scenes, avoiding direct and explicit representation. Instead of following a linear narrative, these elements encourage the viewer to decode and identify with them.

Once we get deeper into the main themes, Ho Jae Kim explains how the central notion of purgatory eventually inspires all his work. He envisions purgatory as a transitional place where things can happen. However, everythingng is still suspended, in a potential or uncertain existence, which leaves just the option of waiting for their manifestation or completion.

He explains: “Beyond the religious, there are many purgatories in our contemporary lives when we are neither here nor there but somewhere. Whether it is searching for one’s identity, sitting on a long flight between countries, or walking under endless scaffolds and construction sites in New York, we exist in and around indeterminate states.”

Therefore, his paintings are located in a liminal space between real and unreal, fiction and chronicle, subconscious, dreamscape and life: they represent that moment where everything we felt and perceived, or imagined and dreamed, is still in elaboration, awaiting a necessary meaning-making process which sometimes those hints would eventually just defying.

From purgatory themes, Kim has created many variations, evoking those transitional existential moments we experience daily. As Ho Jae Kim pointed out during our conversation, we all remember mostly moments of celebration or suffering. Still, most of our lives happen as we go through these transitional and liminal moments and spaces that take us to the event.

As our conversation develops, we finally move from the office to the “working space” in front of the works, where Ho Jae Kim better explains the complex and time-consuming multilayered process behind each of those works.

His digital renderings are first printed and transferred on the canvas. Following the pigment traces, the artist draws the structure of this new image and proceeds transferring, and adding thick swaths of ink and pigment. The final image eventually incorporates much of the process that created it, between the digital sense of plasticity and the classical references it started with. As Ho Jae Kim explains, this is all a very time and labour-consuming activity. The more intuitive part comes in the additional layers of paint he will add once the composition is completed. Building the image layer after layer, his artistic process proceeds simultaneously in an addictive and removing way, replicating some mechanisms of how our subconscious would also work.

Despite the demanding and intense art-making process, Kim is highly prolific, working on multiple pieces simultaneously. In this case, he prepared two shows in one. Those images spontaneously came to him, as he first interestingly developed them in the digital space and then translated them into the painting medium.

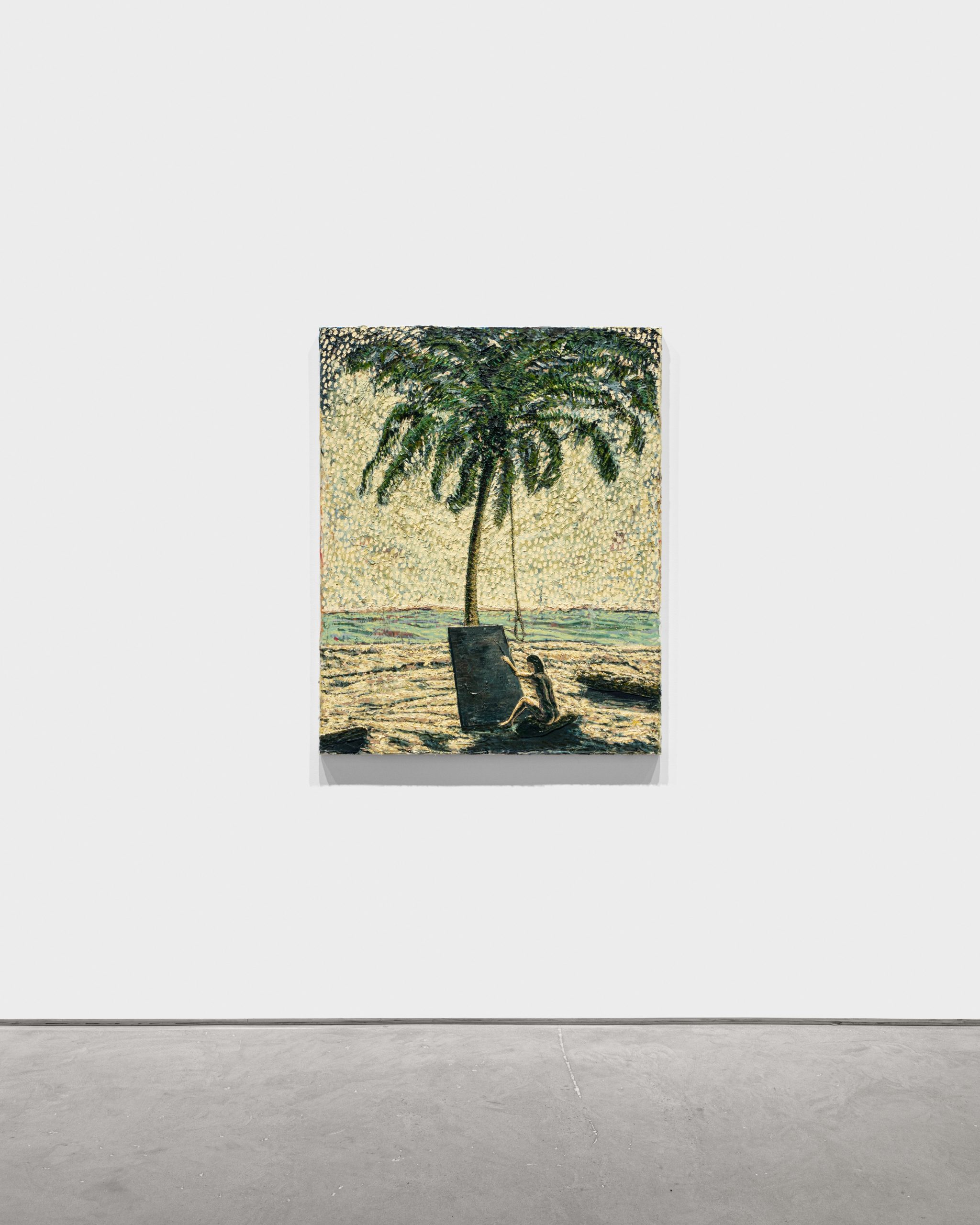

In his works, humanity is often presented in its solitude, confronting highly theatrical settings and the sublime nature: most of the characters in Ho Jae Kim’s work are forced to engage with the surrounding reality and nature in their solitude and minimal existential essence. Facing the sublime of the abyss of the void, these characters often appear more puppets than humans in their drama, characters without a mask forced to accept the limitedness and uncertainty of their destiny as the threat of instability or as the potential for evolution. Ho Jae Kim admits that his work is also influenced by this fascination for Caspar David Friedrich, sharing this similarly dramatical approach that unveils human fragility and finitude when confronted with the endless life circle of things and nature. At the same time, those characters appear to confront a sublime both outside and inside themselves to rediscover and embrace the endless creative opportunities of the soul.

The dramatic use of light also links to deeper philosophical meanings behind this seemingly simple aesthetic choice. Linking to Plato’s Myth of the Cavern, these lights stand as mirages that encourage us to go out and see them in real life, in their true essence, instead of as projections, encouraging inner reckoning of both the inside and the outside world.

Ho Jae Kim explains, “In my works, I create imaginary spaces and worlds lit entirely from behind. My viewers are forced to look into the intense light, silhouetted figures, and environments ahead of them. The light and shadow reference Plato’s allegory of the cave, where the cave prisoner’s reality is only composed of shadows, never the real object or light outside the cave. I extend the imagined space deep into the picture plane and place my viewers in direct view of the monumental objects and light ahead. I hope to allow my audiences to seek the truth beyond the shadows.”

This sentiment of sublime and human finitude and potential reawakening to pursue higher aims is the central theme in the latest series Ho Jae Kim developed for his show in South Korea, Gana Art and at Harper’s in the Hamptons. Inspired by the film Cast Away (2000), directed by Robert Zemeckis, the artist recreated this ectopic narrative following the protagonist Chuck, a man deserted on an island after an airplane crash, who will have to confront so many natural challenges, but first of all with his deeper self, in the solitude. Something that an artist has always to do is work in the lonliness of his studio.

Also, from this series, it’s clear that paintings become a tool for an existential interrogation of the self and its deeper drives and reasons beyond the surface for Ho Jae Kim. Feelings of loneliness, but also a question of individual responsibility, are central to Kim’s works, as his art-making, as for Chuck, becomes both an external exercise and an internal struggle of reconnection with the inner self about the surrounding events. Suspended between this feeling of despair and inner recollection, Kim’s art represents moments of self-contemplation, between a drive for transcendence and the earthy mundane, between the limits of our physical body between needs and desires, and a higher spiritual tendency that art allows us to access to.

As Ho Jae Kim comments, “Before my first solo exhibition with Harper’s in New York, my dream of being a full-time painter felt like an impossible dream. I was truly alone with my paintings in my studio–my deserted island. I longed for someone to visit my studio and acknowledge my paintings, and I exist.”

Ultimately, Ho Jae Kim’s portrayal of the character’s loneliness demonstrates a different possibility of inner and outer contemplation that, although often painful, allows access to more profound truths.

This conversation at the studio on the artist’s rapidly evolving practice makes clear how Ho Jae Kim’s work originates from this deep need and drive for creation that inspires the best art: between suffering and redemption, his art eventually shares those more significant existential questions all humans go through, between the search for a higher purpose and just the desire for complete healthy survival, struggling with a final sense of reality and events that might just beyond human comprehension. Something that we might never be able to grasp and contemplate in its true nature and essence fully, but whose mystery we can at least approach and question through the symbolic language of art.