Where things happen #27— September 2024

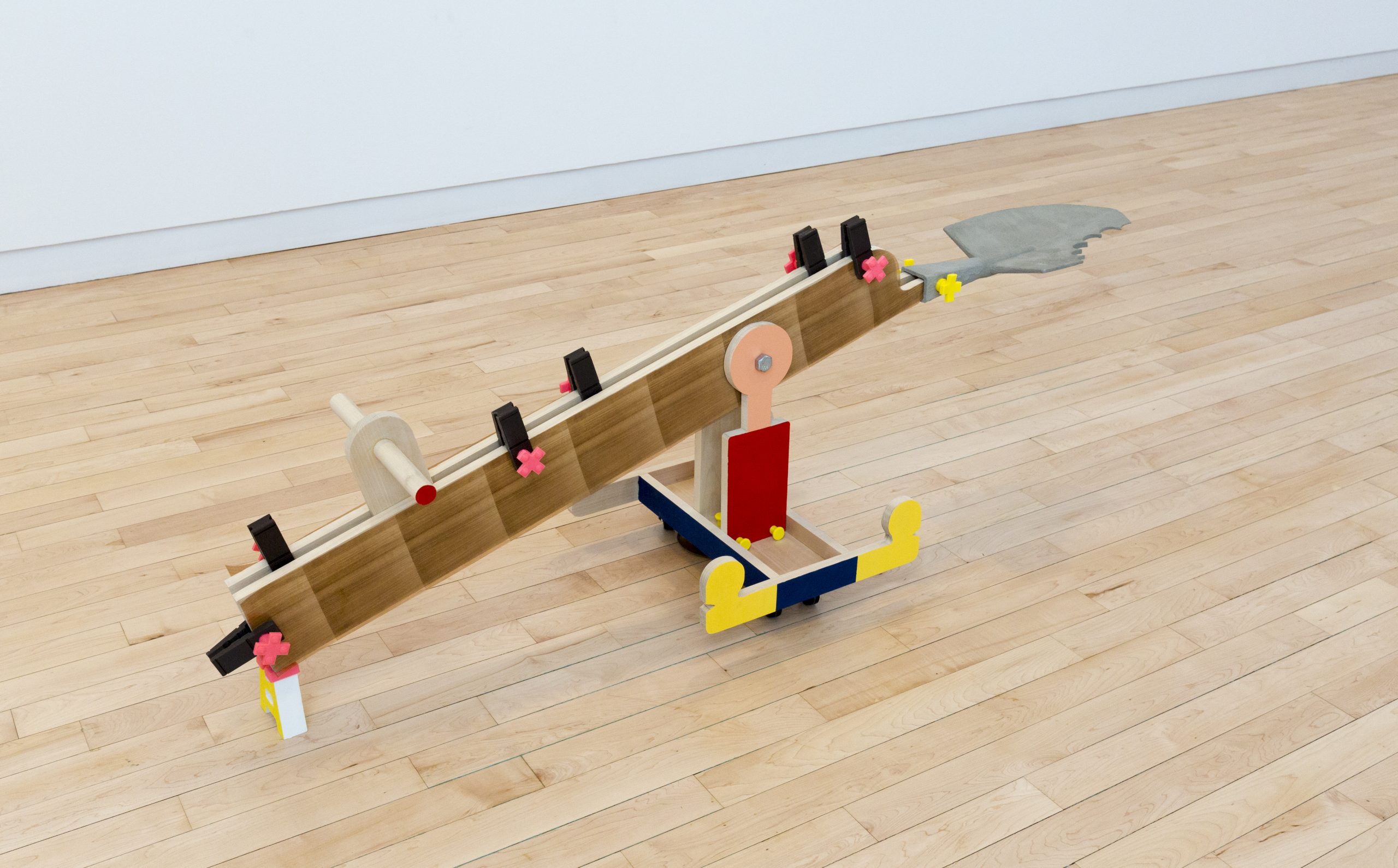

Huidi Xiang’s art practice involves testing and exploring ideas about work and labor at various levels, as well as the interactions between machines and humans that these ideas imply. As a result, her works often resemble prototypes that are ready to be tested in industrial settings but are also designed for use by humans to handle their daily tasks or for entertainment. This tension between creativity and productivity, expression and functionality, significantly influences Huidi Xiang’s artworks and motivates her exploration of a new definition of sculpture that blurs the line between physical and virtual. There is a profound interaction between these two dimensions in her work, as it appears machine-like and industrially produced, yet it is also deeply physical and tactile, invoking human interaction similar to toys and other objects designed for children.

We meet Huidi Xiang in an afternoon in late summer at her studio in Brooklyn, New York.

On the walls are sketches and some images from cartoons, used as mood boards to inspire her works. Most of her sculptures, however, are not made here. Her studio is more of a laboratory, where new objects are conceived and designed in detail before going to production, as well as assembled and tested once they turn from a rendering into a physical part.

As she explains to us, Xiang first studied architecture, and this reflects how she also approached her artistic practice and artistic production: She often designs sculptures with digital renderings and then relies on interaction and exchange with professional fabrication.

Engineering object-making strategies, Xiang envisions new compositional solutions that trigger our memories of more significant dynamics work/humans, often also portrayed by movies and fairytales, more or less metaphorically.

Her visual inspiration and vocabulary primarily draw from American cartoon animations, Disney cartoons, manga and anime: a perfectly designed fictional world that already encompasses many of the dynamics that exist between humans and the material world and the interpersonal interactions between those two.

As the artist explains, some of her most recent works have investigated relations between prey and predator, drawing from cartoons like Wile E. Coyote from Looney Tunes and Tom the Cat from Tom and Jerry. That’s why most of her works look like traps, inviting viewers to question who the real predators and prey are—or if we, too, are part of this dynamic.

When we visited Huidi Xian at her studio, she was just starting to conceive some new works for her next solo. On the walls, images from memorable Disney’s movie moments when various animals help Cinderella to make her dress “They all look happy, it’s presented as a joyful and effortless moment of production,” Xiang comments, “but there’s clearly a heavy labor process behind.”

By applying humor and playfulness they make the labor fun, but this already deploys strategies of human conditioning and guiding used in an operational society,

In particular, for Huidi Xiang, all these felt like finding so many parallels in society and the work system in China, where she is from. Her father, an expert in polymer plastic, has influenced her visual vocabulary, leading to a search for tactile sensations and an “amicable” aesthetic, as evidenced by the accumulation of toys and consumable plastic materials in her boxes. “They serve for inspiration,” she explains.

In diving more deeply into Xiang’s practice, we can observe how most of her works enact a relevant reflection and open exciting questions on the relations between manual and digital labor, investigating how they often have equal intensity in today’s production and consuming systems. Xiang stages these systems of tensions created by hardware that physically exerts force in either our brain or manual capacities. As we further our conversation, it is clear how Xiang’s research touches on some of the most relevant problems of late capitalism, investigating the spatial and temporal effects of inhabiting, creating, producing and consuming in both virtual and physical worlds.

Once realized, it appears quite ominous or clear proof of Xiang’s attitude towards materials making and object production, the 3D printer that, throughout our conversation, restlessly and unabatedly printed and made in plastic a strange structure that is slowly taking shape on an object.

Notably, all of Xiang’s works maintain this level of in-betweenness between virtual and physical and one experience or the other. Huidi Xiang describes herself as a sculptor and creator who smoothly moves in between digital and physical. Intriguingly, everything in her material and visual world appears both playful and threatening.

More importantly, Xiang already embraces this research from the perspective of a millennial artist, fully immersed in a world where the manual cannot exist without the digital and where making, communication and expression move rapidly in a continuous back and forth between those realms that characterize our daily reality. As Xiang’s artistic process highlights, an object can first be perfectly visualized, created, and crafted through pixels and data on a screen. Later, it can be translated into a physical object and sensations.

Almost paradoxically, today all this can now have even less value than the digital ensemble of data and information that created it.

The unicity of Xiang‘s practice is that it engages simultaneously and dialectically with his continuous interplay between digital fabrication with hand-making and finishing techniques. As she continues sculpting in the physical world, she also simultaneously updates the digital model in a flow and continuous exchange between data and materials, digital input and manual, which characterizes our relation with teh world today. “This approach allows the digital and physical objects to evolve together without a strict before-and-after relationship, growing in tandem as the sculpting progresses,” she explains.

This type of reflection raises questions about the politics and dynamics associated with the increasingly blurred lines between the real and the simulated. It also brings attention to the fact that video gaming experiences and real life are becoming more intertwined, both in terms of intensity and the sense of detachment from reality.

In this sense, Xiang’s works appear to emphasize a fundamental reality: at the core of her art lies the idea that the human brain and machines will eventually collaborate in new ways, opening important questions about the risks and threats of one overpowering the other, especially as technologies like A.I. continue to advance and seem increasingly capable of replacing human intervention and roles.