Ilaria Magliocchetti Lombi

You’re a photographer who started working at the beginning of the new millennium. Do you think the role of the photographer has changed since then?

In the ten years I’ve dedicated to photography, I believe many things have changed. I trained during the digital and internet era and witnessed the explosion of Instagram firsthand. Being so immersed in it, I might not fully grasp how revolutionary it was for those from a different generation. Over the years, we’ve been increasingly flooded with images (and news); we’re literally drowning in photographs, and I don’t believe this has led to a greater photographic culture. Quite the opposite: there’s barely any time to delve into anything, making it hard to filter what comes our way. With social media, there also seems to be a strong aesthetic conformity—a flattening effect. In this sense, I think that those who work in photography need to be more mindful and intentional, producing only what feels essential, urgent, and avoiding contributing to visual pollution. There should be more research and less anxiety around constant production. Nowadays, everyone produces a vast amount of photographs and shares them, not just photographers, and this has undoubtedly changed the photographer’s role, especially for documentary photographers. Just think of how war narratives have changed, with events often documented live by those enduring the worst of it.

I don’t believe this diminishes the power of authorial photography; we have more perspectives and narratives now, which is a good thing, helping us move beyond the single, often colonial, gaze of certain types of photography. However, I believe it has placed more responsibility on photographers to take more risks and to break down outdated, unwritten boundaries and rules. There’s much more cross-pollination and less rigidity now. Photography is very much alive, but the world that made it economically viable is in crisis. This seems to me to be a major shift in recent decades: practicing photography without consistent support, being increasingly independent—which often means precarious—is challenging. This situation further silences those who face more economic difficulties, which poses a major risk. We run the risk of seeing the world documented (both photographically and journalistically) solely by those who can afford to do so.

We’re used to seeing all digital channels reveal events and global happenings live. From an informational perspective, do you think we’re at greater risk of superficiality?

I believe I partially answered this earlier—yes, definitely. Everything is very fast, a continuous flow, and there’s no room for in-depth analysis, reflection, or source verification. We’re already on to the next image or headline.

You started your career documenting the emerging independent Italian music scene, focusing on artists who have voiced important social issues. Do you think this early experience contributed to your growing interest and commitment to certain themes?

I believe it was exactly the other way around. I approached that world and immersed myself in it because certain themes and that language strongly resonated with me; they were mine. For the first time, there was music in my language that spoke to me. Being part of those projects by contributing my vision and creating imagery with those artists was very powerful for me. Ten years ago, Italian music was completely different from today’s scene. The independent and underground world was light years away from what was on TV or in the charts; it was a resistant, genuinely independent form of music that operated with very few resources. Those were wonderful years, and the relationships I built with those artists are ones I still hold dear today. I owe them so much because they were the first to believe in me and my photography, to support it financially, and to trust me.

We’re living in a time when migration issues are at the center of public debate, as is the situation of many young people who, despite growing up in our country, still don’t have Italian citizenship. Why, in the Athletes without Citizenship project, did you choose to use sports to address these issues?

Sports served as a Trojan horse. I’ve always been interested in the topic of citizenship, which I believe is one of the most glaring injustices in this country. I’ve always wanted to tell and make more visible the absurd situation experienced by more than a million young people in our country. I sought different channels but always hit a wall. Newspapers and magazines were never interested; there was always considerable confusion about the topic of migrants and citizenship for those born in Italy or who arrived here at a young age. I needed someone to publish the work, primarily to give it visibility, and also because I needed funding to produce it, as I envisioned a studio series done a certain way. A universal, popular, and mainstream theme was required. We were on the eve of the Olympics, so I thought sports might be the answer. Then I realized it could also serve as a tangible symbol of the missed opportunities faced by many young people.

Sports is merely a symbol, as we shouldn’t imply that one must be a sports star, genius, or hero to gain citizenship. It was simply a means to tell stories: the text portion of the work consists of firsthand testimonies written by the subjects themselves, with no journalistic mediation. The images and entire process were tightly collaborative. For me, it’s essential, especially if I choose to tell the stories of marginalized individuals, that the work be shared step-by-step and that the texts genuinely represent the subjects’ voices. I ensure that participants feel actively involved in what we’re doing rather than passively subject to my vision or photographic act.

Do you think that undertaking a project titled Extraordinary: Women of the Present clearly indicates serious social issues that require attention?

Unfortunately, yes. Our country has a problem with women—cultural, political, and social. There’s still a long way to go, and a project like this is only a small step, but it’s important. It’s essential to tell girls that there are countless ways to be, a constellation of possibilities. This project aims to offer them a pantheon of women who have found ways to realize and express themselves beyond discrimination and gender stereotypes. Extraordinary was born from curator Renata Ferri’s idea (as part of Terre des Hommes’ campaign for the defense of the rights of girls) to turn the narrative around—not to talk about the problem of stereotypes and discrimination, but rather to positively highlight those who have overcome these obstacles, those who are making a difference today. After the stages in Rome and Milan, the exhibition, organised by Gramma Studio, will be shown in Genoa, at Palazzo Ducale, from 16 January to 16 February 2025.

PHOTO CREDITS

Le luci della centrale elettrica, Terra, 2017.

Afterhours, Hai paura del buio?, 2014.

Tre allegri ragazzi morti, Sindacato dei sogni, 2018

Zen Circus, Canzoni contro la natura, 2013.

Dente, 2020.

Athletes without citezenship. Great Nnachi, astista, 2021.

Athletes without citezenship. Najla Aqdeir, velocista, 2021.

Athletes without citezenship. Ghassan Ezarra, velocista, 2021

Athletes without citezenship. Youmna Nasri, taekwondoka, 2021.

Athletes without citezenship. Danielle Madame, pesista, 2020.

Straordinarie. Diletta Bellotti, attivista, 2022.

Straordinarie. Sabrina Efionay, scrittrice, 2022.

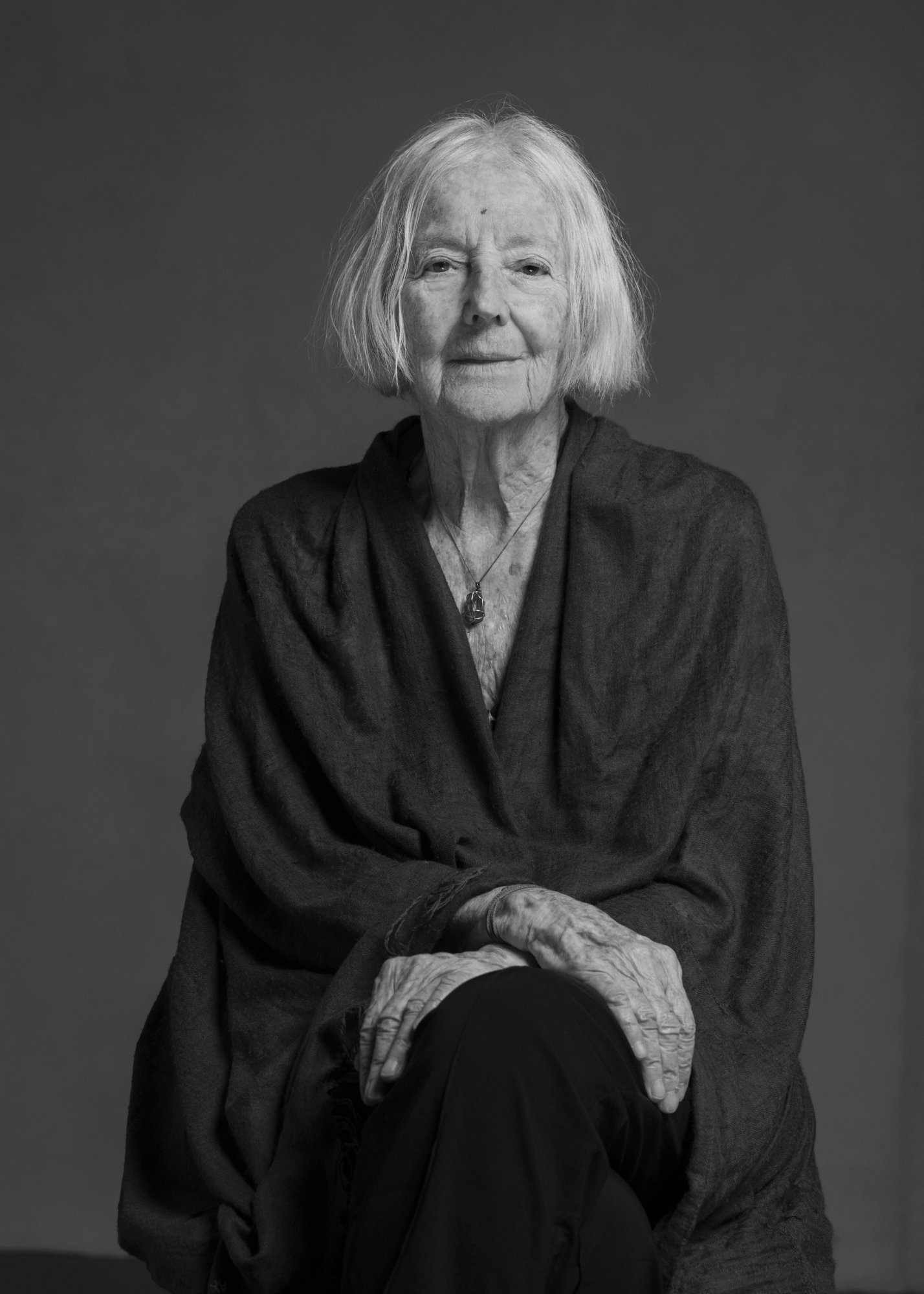

Straordinarie. Isabella Ducrot, artista, 2023

Straordinarie. Marzia migliora, artista, 2022

Straordinarie. Alina Marazzi, regista, 2022.