Terry Atkinson

January 2026

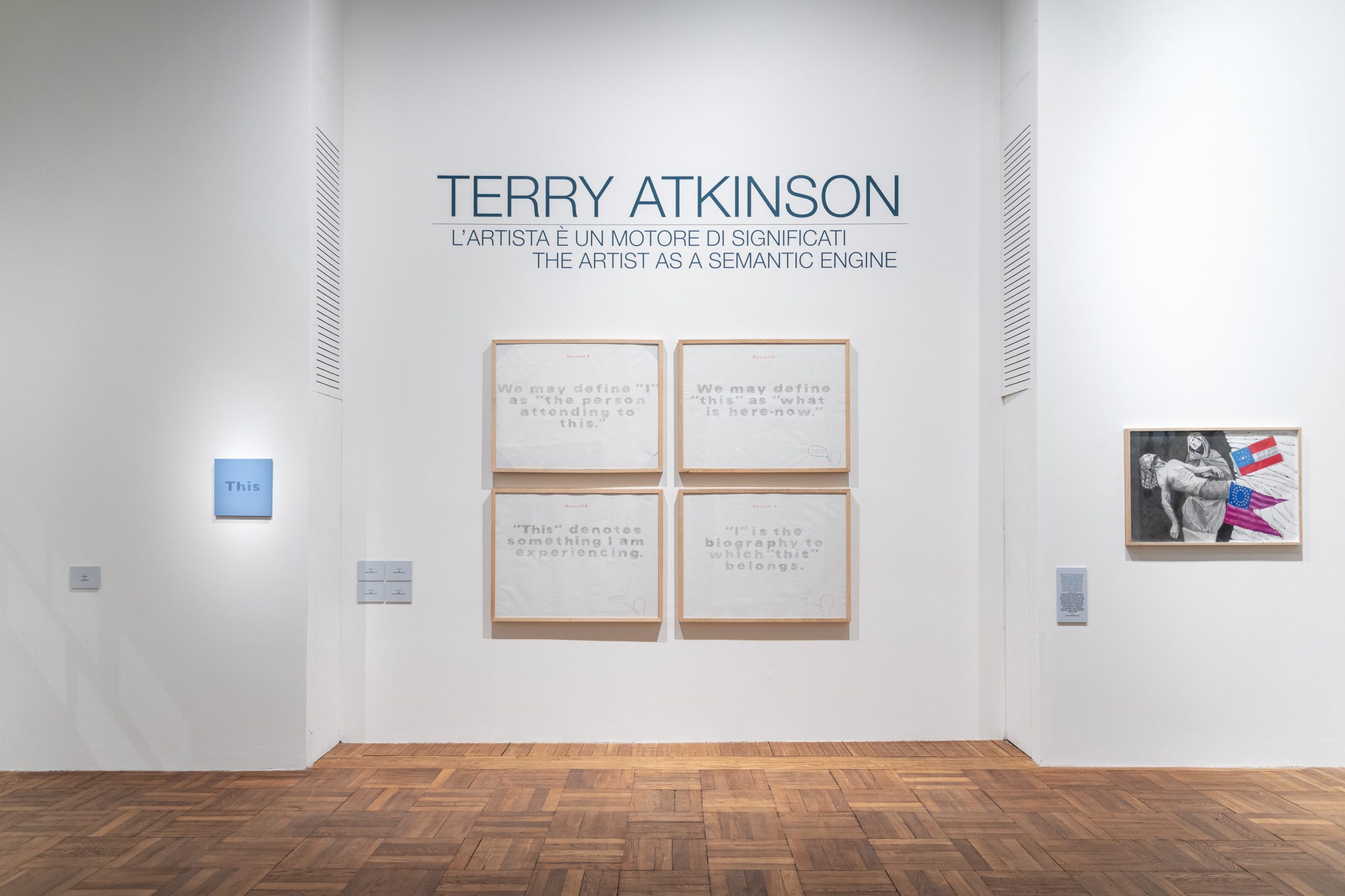

Ca’ Pesaro is presenting the first solo exhibition in Italy by an artist who has left his mark on the history of contemporary art. Entitled ‘The Artist is a Generator of Meaning’, and curated by Elisabetta Barisoni and Elena Forin, until 1 March 2026, it showcases the crucial turning points in the work of British artist Terry Atkinson. Active since the early 1960s, Atkinson has traversed Conceptual art, constructing an artistic practice that serves as both historical testimony and a revelation of power dynamics, building awareness that goes beyond the surface of images.

In the following interview, we discuss his long career with him, which spans conceptual and figurative painting, as well as linguistic research and iconology.

The theme of war has been present in your work since the beginning of your career in the 1960s. The Venice exhibition displays some paintings from the Enola Gay series — monochromes with vivid, saturated colour fields from which an ominous silhouette of a bomber approaching with its load of destruction emerges in the form of a dot or an irregular pencil line. As well as functioning as a critique of the modernist monochrome, these works also blur the boundary between the figurative and the abstract. I would like to ask you about the significance this theme holds in your practice. Curator Richard Birkett writes that your interest in war stems from the fact that it ‘structures and defines the understanding of history as enclosed by ideological imperatives’. Is your interest in this theme because it shows how history is transmitted and constructed, particularly in its violent and imperialist dynamics?

A foundational claim driving my practice is that any claim to transcend ideology (i.e. any claim to be non-ideological, any claim to be ideologically neutral) is itself an ideological claim.

The issue of figuration versus abstraction also emerges in another series on view, the Goya Works. Here the black background recalls the dark atmospheres of the Spanish author’s Caprichos, while clots of paint alternate with photographic collages. These works are reflections on perception, where abstraction—now fully assimilated by the viewer’s accustomed eye—becomes in turn a figure, namely something to be read. To echo critic Giorgio Verzotti, your work defuses “that which conceals the contradictions of the social order.” I am also reminded of Marcel Broodthaers’s remark that “art serves to prevent ideology from becoming invisible, that is, from becoming effective.” In the end, is art a way of revealing the mechanisms of the political dynamics in which we are unconsciously immersed?

A frequent claim for abstract art was that it was transcendental, equally frequently this kind of claim rests on some such presumption as beauty transcends ideology. This, in turn, identifies, at foundation, that beauty is truth. Thus the claim that Rothko’s paintings exist in a kind of sealed off domain of visual beauty somehow representing only themselves! The argument frequently continues that these objects are a realization of something called a ‘visual language’, or, its existential correlative, are objects whose value is purely visual. When pressed, adherents of this kind of view, faced by some such as the question, does this language have grammatical rules? (surely a defining characteristic of any language) blithely answer this language does not need rules, does not need a grammar. The paintings just are beautiful. At this point, the argument becomes elusive sophistry – inevitably having to fall back and reduced to some such slogan as ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder.’

During the Cold War, abstract art was championed in the West as a primary symptom of Western freedom, of Western free expression, of Western self-expression. In the art schools self-expression was promoted as a supreme index of Western democratic virtue with few questions asked concerning the concept of the self, how it was formed and who or what formed it. At best, such an inquiry was argued to be an appropriate problem for philosophy, and not at all a topic that art practice itself need be concerned with. Again, in Western art schools it was widely presumed there was such a thing as an authentic transcendental self which could be, so to write, dredged up from some unspecified depth – not least, for example, through techniques/practices such as painting and sculpture. A highly glossed version of populist interpretations of Freud’s works were often flaunted as evidence of the existence of this alleged deeply imbedded authentic self. The idea of a propaganda influenced self, a propaganda made authentic self was ipso facto taken to be impossible. Within this kind of framework the many thousands of Nazis were taken either to be inauthentic selves or not selves at all. I once heard a prominent art critic move, unwittingly, alternatively between both positions as this critic was pushed into logical absurdity by the questions of his opponent. But such confrontations are widely bypassed in art world conversation since art world constituents widely conform to the belief that beauty transcends ideology. Attempting to take account of this issue has had significant input into my ideas about my practice for over fifty years. The Western view of Soviet Socialist Realism as a heavily propagandized art practice held out by the West in an alleged direct contrast with Western abstract art arguing that, for example, Rothko’s work transcended propaganda, as if such work was untouched by propaganda was itself Western propaganda. This bunch of concerns has, I hope, furnished me with a resonant set of question which I think were first precisely raised for me in my work with Michael Baldwin in the years before we formally and publicly founded A&L (1966-68).

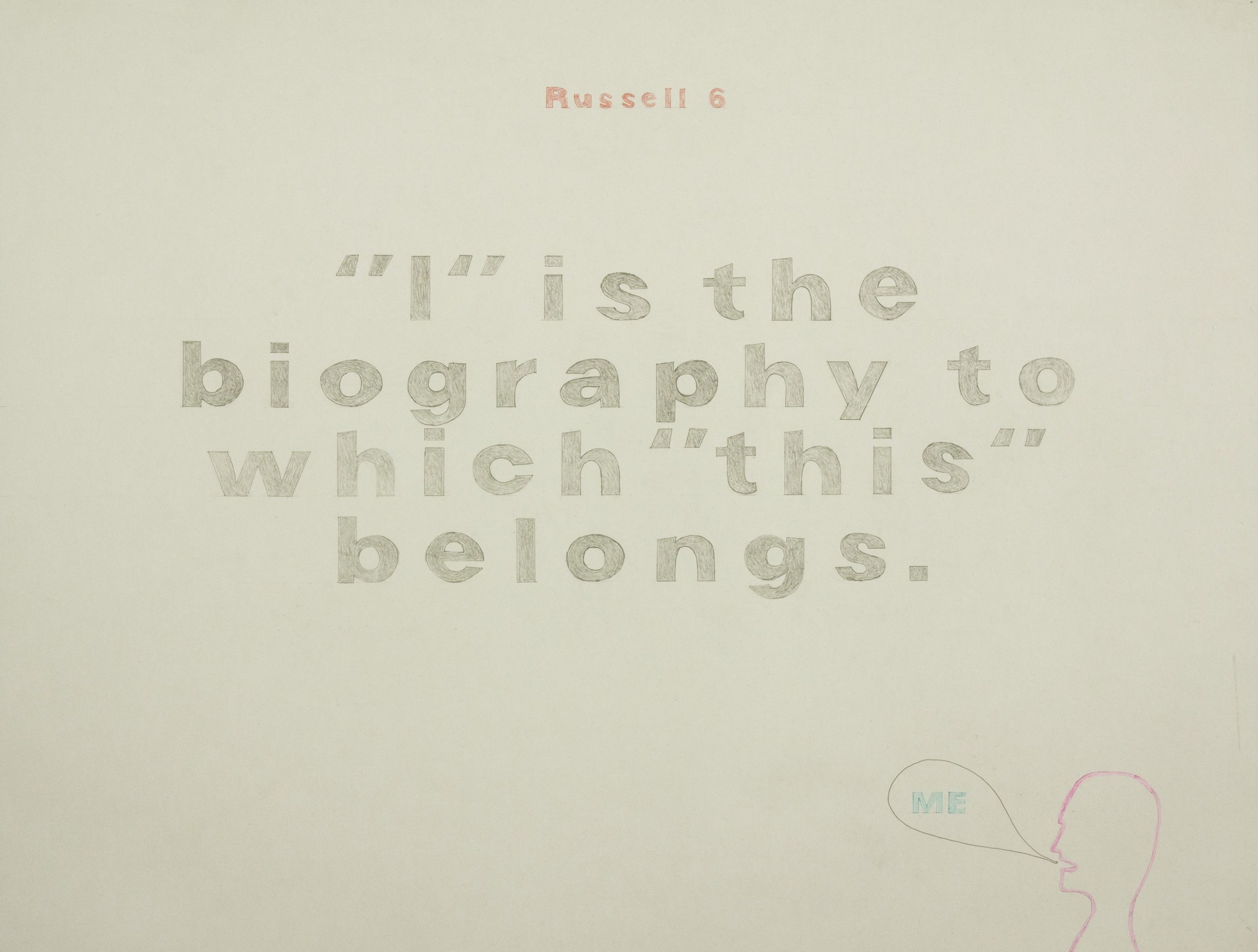

Other works in the exhibition—This and Russel 6, for instance—explore the tension between thought and vision, and the idea that seeing is separate from thinking.

In his essay Images and Words, Gombrich reflects on the equivalence between images and verbal assertions, concluding that no real symmetry exists between the two; without context, an image retains an ambiguity that language, to a lesser degree, does not. Reading a visual artwork implies that there is an alphabet, a grammar; thinking without a language seems paradoxical because it risks leading nowhere. This is also why your works are often accompanied by very long, open-ended titles, oscillating between irony and playfulness—“attempts to protest against the hegemony of the visual,” as you have stated. What is the relationship between images and words in your practice? Are images always translatable?

What does Gombrich mean by ‘real symmetry’ – In my view, is a firm adherent that there is some such thing as a ‘visual language’, thus I reject the basis of his writing. Mattia, you answer Gombrich’s problems yourself, I quote you: “Reading a visual art implies there is an alphabet, a grammar; thinking without a language seems paradoxical …” Certainly since I first seriously studied Wittgenstein’s Private Language Argument (hereafter PLA) with Michael Baldwin in 1966 I have thought the concept of a ‘visual language’ to be absurd. Coming across and studying the PLA confirmed my suspicions about such notions as ‘visual language’ that I had harboured since I first heard it repeatedly used by my tutor at Barnsley Art School in 1958 in reference to Braque’s work. My history with all this, I guess, could not help but contribute to my ironic approach to the titles such as that of Gombrich’s book, Images and Words, and on reading the book I found it absolutely confirmed my expectations of and predictions about the book. Gombrich’s mysterious ‘no real symmetry’ came back floating into my thinking when reading Martin Butlin’s introductory essay to the Tate Gallery’s William Blake exhibition in 1978. Blake’s insistence on imbedding text into the picture surface soon rendered incoherent Butlin’s implicit presumptions avowing the existence of some such as ‘the purely visual’ and, equally, Butlin’s attempt to confine ‘the visual’, on the one hand, and language, on the other, into separate laggers, become clumsy and gauche.

In 1974 you left the conceptual collective Art & Language to focus on an individual practice, and through a lateral shift you returned to a medium that is the antithesis of Conceptualism: painting—drawing also on the tradition of Socialist Realism.

This occurred at the beginning of the postmodern era, just before the shift towards the personal and the triumph of Neo-Expressionist painting in the 1980s. You have said that you sought to avoid the alienating effects of Conceptualism. Could you revisit the rupture that occurred during this transition, which you have described as moving ‘from the we to the I’? What was alienating you from Conceptual art?

My attempt to focus on Soviet Socialist Realism was something of a desperate attempt to emerge from what, at that time, seemed the all-consuming swamp of the race to avant-gardism. My own particular figureheads of that attempt were literary figures as much as pictorial ones. Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell was particularly prominent and Primo Levi’s works were a buzzing background throughout the period as was Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, a book that had engrossed me since I was 18, when I read it a second time, whilst still at school, became heightened yet again alongside Rimbaud’s work. Incidentally I first came across the work of Emily Dickinson during this time, I was very engaged by the fact that she wrote a lot of her poetry throughout the American Civil War. Along with Moby Dick her poetry has remained at the centre of many ideas I’ve tried to feed into my practice ever since. The specific pictorial resources I turned to were Soviet Socialist Realism, Goya’s Caprichos and many of his paintings, Hieronymous Bosch’s works, and not least, Jacques Louis David’s work and, again not least, the example of David’s life. This interest was further greatly expanded when, a couple of years or so later, I attended an entire series of lectures on David given by Tim Clark at Leeds University in 1978. Above all, in respect of pictorial resources I embraced to in the period 1974-78, l returned to the reservoir of WW1 photographic images I had kept since my first sojourn into the subject of WW1 whilst at the Slade in 1961-62.

I would like to conclude by returning to the beginning: the title of the Venice exhibition defines the artist as an engine of meaning. At times you have described yourself as a “history-reporting artist,” a witness and conveyor of the meanings of history. However, I am particularly interested in the so-called AGMOAS—the “Avant-Garde Model of Artistic Subjectivity”—a definition you coined in the 1970s. Could you tell us more about this notion, and how, over the years, the role of the artist within the artistic ecosystem has changed?

I’ve mentioned the ‘race to the avant-garde’ above – it seemed to me that Conceptualism had indicated some kind of terminus of the ongoing early seventies claims that modernism was at a kind of critical thinking nexus. I first became suspicious of and rapidly paranoic about the model of the artistic subject in the mid-seventies, not least of myself and my practice as an example of it. In the couple of years after leaving A&L I reflected a lot on the matter of the avant-garde subject model of the artist. I argued, with myself as much as with other people, that the artistic subject had reduced itself throughout the earlier decades of the twentieth century, to a comfortable accommodation of the artist as a self-confirming centre of truth. The term ‘self-confirming centre of truth’ I only came across much later in the eighties, I think in one of Chris Norris’ books. From 1974 to the point of coming across Chris Norris’ term, I tended to use some such phrase as ‘artists rhetoric and statements about their work are too easily believed and too widely taken to be the case. Ongoing, some of the rhetorical events that led me to such a conclusion are Warhol’s easy facility to pump out entertainment one-liners, Koons’ boasts about both himself and about Duchamp, and Anish Kapoor’s long monologues about the spiritual content of his work. Whilst the model of the artist seemed to me by 1974 to be frozen in its own vaingloriousness both by artists themselves and equally their widely expanding camp-followers, proclamations such as Warhol’s at that time and later those of Koons and Kapoor serve to confirm my analysis. All this self-satisfied rhetoric seemed to me to characterise an artistic subject frozen in its own loudspeaker system, which at an increasingly booming volume elided practice into career. This lack of discerning between practice and career often illuminated and spectrally corresponded to the division between artists who implicitly often siphoned off aesthetics from ideology arguing that aesthetics was not ideological, that it transcended ideology, and artists who claimed that the claim to transcend ideology was itself an ideological claim. Artists of the latter persuasion were hard to find in the rampant vaudeville of the race to the avant-garde of the seventies, eighties and nineties.

PHOTO CREDITS

Botched-up art work depicting intra sexual, intra working, class sadistic act under the Emergency Power Act, the two acts undertaken in the service of imperialism, 1981, mixed techniques on paper on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria l’Elefante. Exhibited in “War is over! Peace has not yet begun”, 2023, Gallerie delle Prigioni, Treviso.

Bath Gren Enola Gay Mute, 1992, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

Russell 6, 1995, pencil on paper. Courtesy of collezione Artenetwork Orler

Exhibition views, L’Artista è un motore di significati, 2025, Museo Ca’ Pesaro, ph. credit Irene Fanizza

Goya Work, Letter from the Artist, Series 2 No. 6. Family-map modernist surface tourer. Foreground/background Xeroxes. Ruby and Amber in front of the incinerators at the preserved Natzwiller-Struthof Memorial Camp. Vosges, August, 1985. Background/foreground surface mutant. Dear Modernism, 1986, mixed techniques on board. Courtesy of collezione Artenetwork Orler