Where things happen #14—May 2023

In first meeting Lily Wong in person, you can immediately perceive the strength of her character and energies. She is as she presents herself: outspoken, clearly aware of herself and her art.

Before the meeting at her studio in Greenpoint, Wong had sent me a message of highly detailed instructions of how to get there. It was the end of a long day in New York, but I followed them step by step, and I didn’t get lost. I wish all artists were the same, providing such clear information in advance.

Her studio is in a building we have never been to before for this editorial series, but also full of artists in this once industrial only but soon became hype neighborhood.

Wong reveals to be extremely welcoming, and ready for a good conversation about her work.

She speaks confidentially about it, but without any constructed narrative in her hands: promptly responding to the questions I address her, her replies lead immediately to the next, in a spontaneously thoughts triggering conversation you would always love to have when visiting an artist.

As she tells us, Lily Wong actually started her art career in printing, graduating at the Rhode Island School of Design, then followed by a MFA at Hunter College, New York.

The artist’s inclination towards paper as preferred medium is still the core of the work: as she explains, this allows her to genuinely reconnect with the tradition of Sumi ink paintings, and with her Asian background.

Wong, in fact, constantly taps into Chinese culture, despite refusing to restrictively pursue any identitarian quest or claim: she doesn’t want her practice to be reconnected only to this, feeling it very limiting compared to the broader messages and instances she wants to bring into her work.

Instead, her scenes often appears to be imbued with what she describes as “persistent longing” for something we feel we live with as inherit from our families, but that may also translate into a nostalgia for something out of reach, intangible and ephemeral for us as already out of this time and this place.

In particular, during our visit Wong admits how recently she has more often drawn inspiration from Asian traditional knowledge, but always approaching it with something inherited heritage, absorbed through her family and community she lived in, that she wants to retrieve.

From a purely visual point of view, it’s quite clear how her work escape any identification with a spèecific cultural and geographical canon, freely absorbing and employing both elements of Western and Eastern aesthetic, and philosophy: her figures may remind some anime and manga characters, but are also dense in references to the Western history of paintings.

On the other hand, the way Wong approaches the space, focusing the airy weight of atmosphere rather than a rational perspective-based description of elements, is something closer to traditional Chinese and Japanese paintings and prints.

The Asian, and in particular Chinese cultural background, eventually comes in also in terms of contents, and the philosophical and existential approach her figures seem to suggest.

Over our visit, Wong in fact confessed how lately she has become interested in exploring different conceptions and perceptions of the body and its relations with external factors, diving into some alternative approaches such as the one we find in traditional medicine practices in East Asia medicine, in particular.

In fact, the East Asia, and Chinese ancient medical traditions stand somehow at the opposite of the Western paradigms: not necessarily bound to mechanics of cause-effect and the study of only physical effects and causes, these medical practices are based on a more holistic conception of the body, which focuses on energetic connections between the individuals and the universe, seeing the functioning organism as a microcosm bound with a broader macroscopic order.

These considerations appear much closer to ancestral or indigenous notions of unity system between individuals/nature but, at the same time, also echo the concept of “mindful body” as described by Nancy Scheper-Hughes suggesting the necessity of more anthropology-based medical practices, studying the body beyond the Cartesian Dualism of minds-matter, physical and no-physical, and as something to be observed at the intersection between nature and culture.

Some of the works Wong was working on at the moment of our visit were already exploring these both philosophical, anthropological and spiritual realms, embodying these concepts in imaginative scenes made of saturated atmospheres and irrational proportions.

As she confesses, she has been pulling from a lot of imagery around East Asian medicine books, inspired by this idea of how bodily perceptions are eventually so entwined with conceptions of personhood/the self, and its relations with the rest of the world.

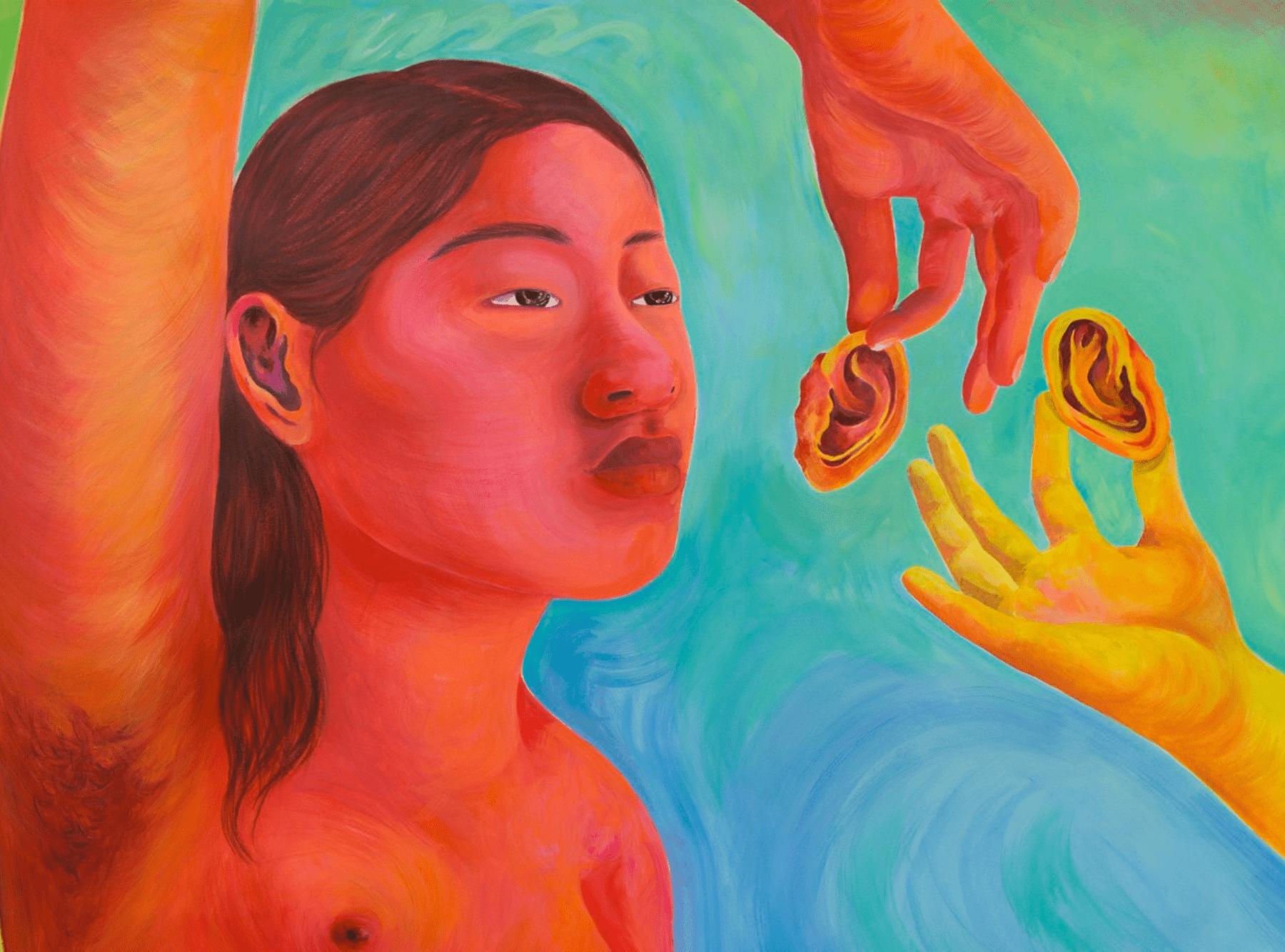

Among the almost completed works, Entrance/Ear leaving soon for the Dallas Art fair, appears emblematic of how the artists is introducing these considerations in her works: two figures, apparently the same person but depicted in different colors and attitude, are floating and interacting at the same time in a undefiable space, which seems already located between body and both its inner and outside perception.

At the very center what seems like an ears exchange is happening inside an ear-like shape: the cryptic image is actually inspired by the movie, Blue Velvet, when the character Kyle Mclachlan discovers this specific mody body part and the camera dives into, the plot begins to unfold. Ears, however, are recently becoming a recurring motif for the artist, seeing in this particular part of the body this sort of portal that connects a microcosm of the self, to the whole of the world surring it.

As Wong admits, as this particular piece shows, her work is getting more surreal as her characters try to embody this search for a different way to perceive and read humanity, and its relations with the surrounding.

The artist declares to be deeply fascinated by this specific idea of the body as a portal, something with which we negotiate our position in the universe.

With that in mind, she is purposely forcing proportions and movements, prioritizing over realism a specific reconsideration of the perception and thus representation of the human body, focusing in particular on the powerful intertwining of its physical and mental energies.

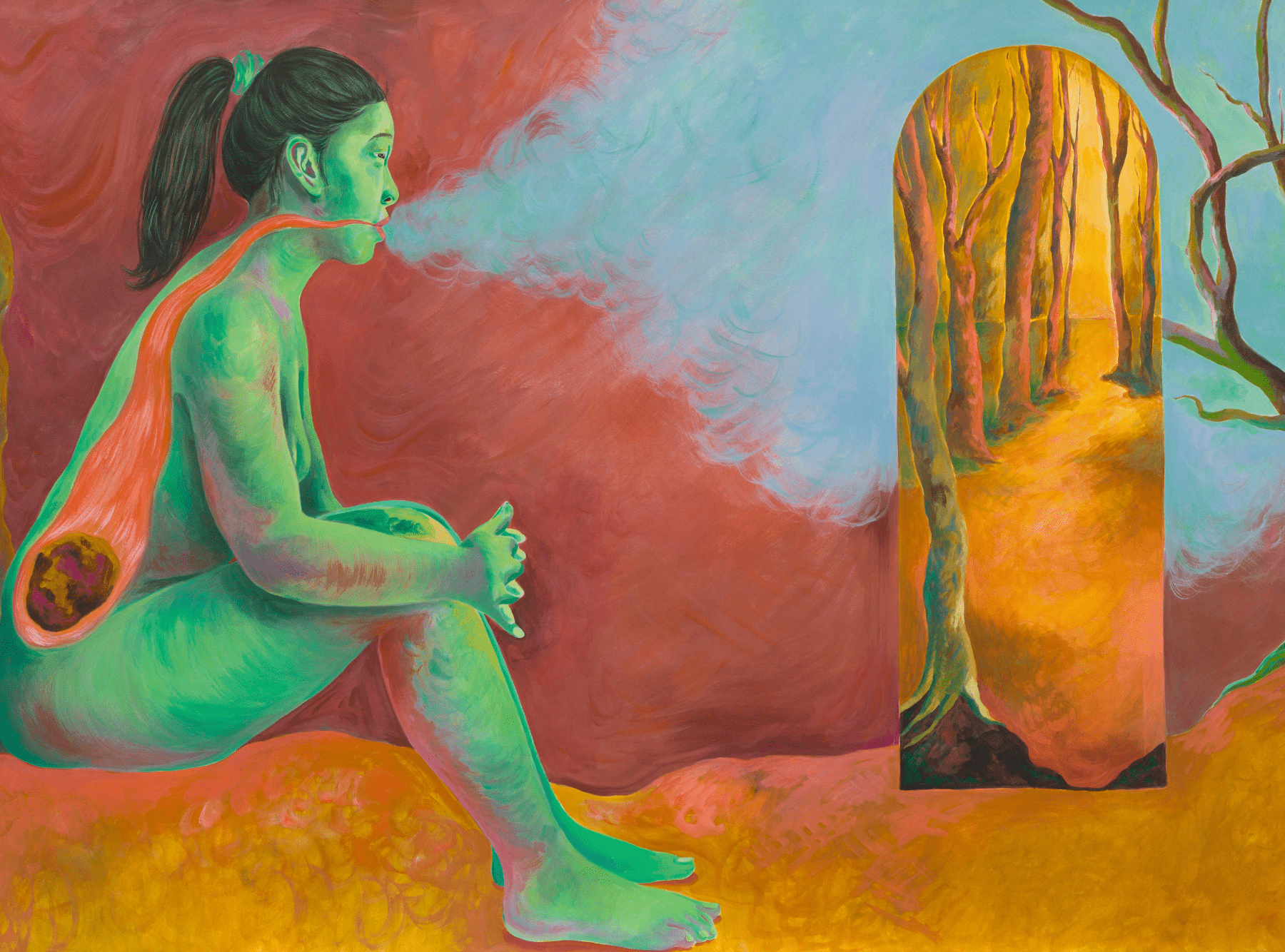

This becomes more clear in another work, Wind, for which Wong draws inspiration from this idea of breathwork as a way of strengthening ‘The Gate of Life’ in Traditional Chinese Medicine, to provide the body’s ‘internal fire’ in reconnecting with the universal cycle of energies.

From these considerations, in depicting the human figure Wong deliberately challenges the usual perimetres of bodily perceptions and emotions, suggesting a more fluid interconnectedness by positioning her scenes in this liminal space between the inner and outside world.

Also for that reason, we can understand why her characters are therefore mostly acting and performing in otherworldly atmospheres and landscapes, suggested by the artist’s highly imaginative use of colors, already unbelted from reality.

Wong confesses how the potential of color is another recent discovery for her: coming from printing, she was previously inhabiting a purely black/white and graphic visual universe.

Since colors came in her works, she started to freely explore the intense metaphorical and emotional force they can have, and the narrative subtleties they can create: these glowing and vivid colors are often used by Wong to embody energies, allowing her scene to explore and suggest alternative emotional, psychological and energy connections between the figures and the surrounding.

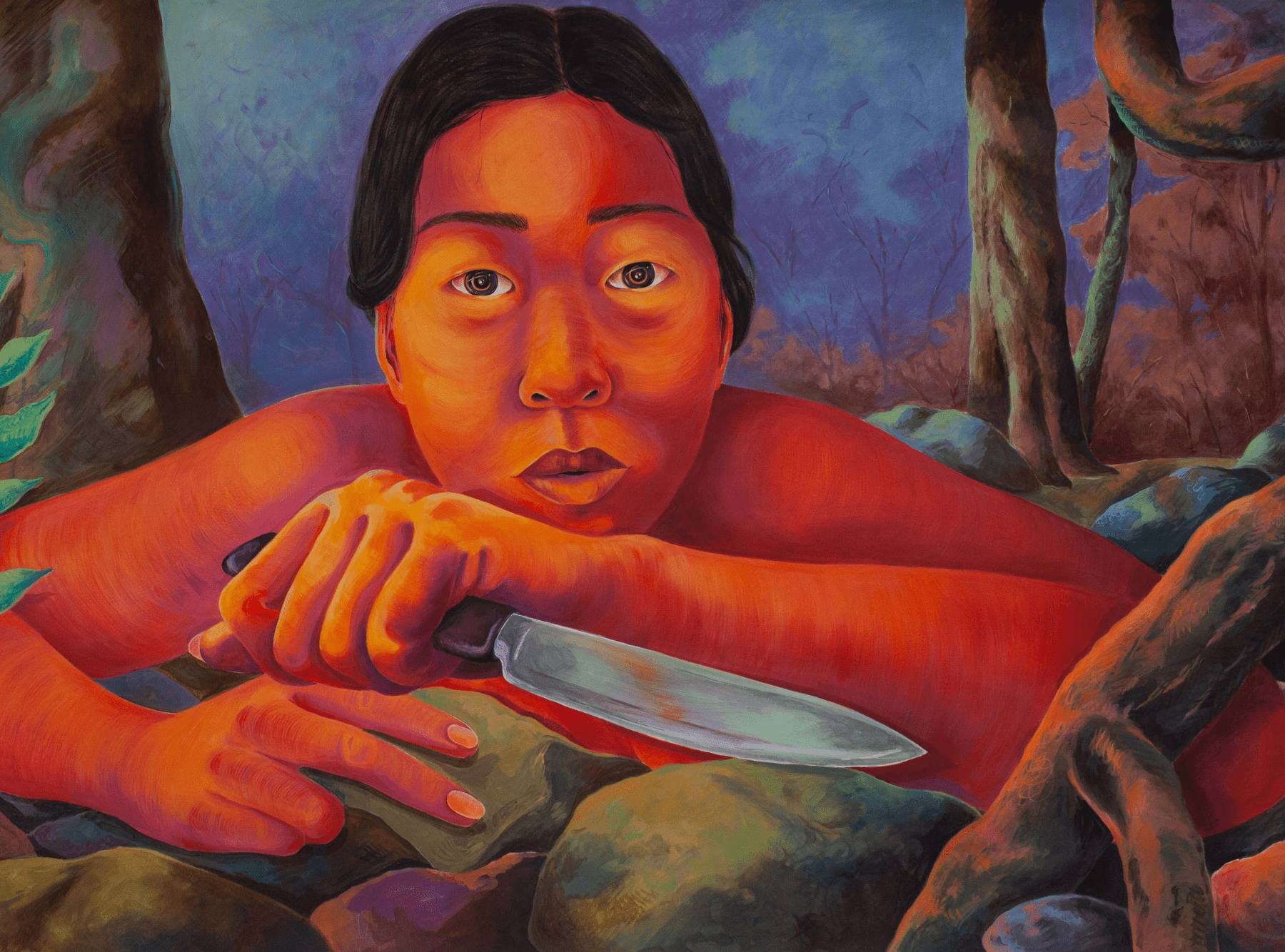

Sometimes the artist’s use of colors tends to turn even more dramatic, fueled by a specific cinematic approach to the scenes she started to introduce, which isolates specific movements and expressions where these energies manifest through the body.

Additionally, Wong figures often appear in a transitional status, involved in an on-going metamorphosis that suggest the possibilities of a “self on flow”, open to a constant transformation and evolution, responding to the circumstances.

Ultimately, with her nuanced narratives Lily Wong successfully visualizes a more fluid idea of personhood, suggesting a relevant reflection on the multifaceted and no binary nature of both one’s personality, and one’s sense of the world around.

In this sense, Wong’s works also encourage a more open-ended notion of both individual and universal reality, that forces us to accept both as a flux of ever changing perceptions and realizations, that starts with cultural inheritance and expands in the openly endless way to perceive and feel the world and the surroundings.

This specific mental and existential space of “openness to the world”, in fact, is what allows us to overcome this longing for something far and lost, embracing the necessity to be just open to the world and its diversity. Because, as philosopher José Ortega y Gasset once said, ‘I am I and my circumstance; and, if I do not save it, I do not save myself.’

Thus, life is not the self; life is both the self and the circumstance, happening around and translated inside, that contribute in shaping one’s sense of the self, and concurrently of the world.

However, these aesthetic concerns also seem to have been challenged by disruptive artists such as Duchamp, as first, following him with a host of conceptual or process-based art. By now, we can take for granted that idea prevails over the physical and factual object as artwork, and this can often be protected and certified as instructions or words by its author when too immaterial.

This is also what critic Robert Adrian pointedly observed, commenting on both the aesthetic and conceptual contact point between digital and conceptual art, when he commented: ”An electronic space in particular, is very easy to imagine once you have grasped the idea of conceptual space for an artwork”

In Cabret’s works, the question now is whether this “idea” to protect and consider the true essence of the artwork should be the code activating the process, or rather the intuition and willingness of the artist to give the computer this specific input to generate the artwork.

Regardless of outcomes, this issue already appears to perfectly mirror some of the most important concerns that should be investigated today when analyzing the relations between human intellect and creativity, and new technologies and machines one.

In the culmination, by translating the experience of these digital technologies and abstract codes into a visual language, Cabret succeeds in demystifying digital and technology based processes, embarking on relevant discussions of how they work, interact, mediate and influence our daily perception and experience of the world.