Features #18 — April 2023

LYDIA OURAHMANE IN CONVERSATION WITH NICOLAS VAMVOUKLIS

Lydia, I know you spend time between Algiers and Barcelona — where are you at the moment? Could you tell me about your working space there?

Now I’m in Barcelona. I just returned from Algiers, where I opened an exhibition with rhizome hosted at Les Ateliers Sauvages. It was the first time I showed my work in Algeria. I did a talk the day after the opening, where many people attended that I’ve worked closely with on my past two projects: the film “Tassili” and “Barzakh,” an installation that involved moving the entire contents of the apartment I rent in Algiers to Basel, Marseilles, and Ghent then back again. Nadira Laggoune, who used to be the director of the Museum of Modern Art of Algiers and was the reason I moved there in the first place, was also there, so it was an important moment — to spend time with and talk about all the projects that were anchored to and mobilised by that place.

I can work from anywhere… I just need a computer and a phone.

I can’t stop thinking of your exhibition “Barzakh,” which addressed themes of displacement, border, territory, and nation-state. The main question was what makes a home. Is it even possible to define that? Is it an imagined construct?

That question is always unresolved. The attempt to understand what home meant for me gave agency to that work. ‘Barzakh’ means limbo; it is a state of knowing-unknowing. I have always lived in-between. And by living, it is not about where your body is. Your points of reference are stretched between several places you understand your position through the distances that ground you.

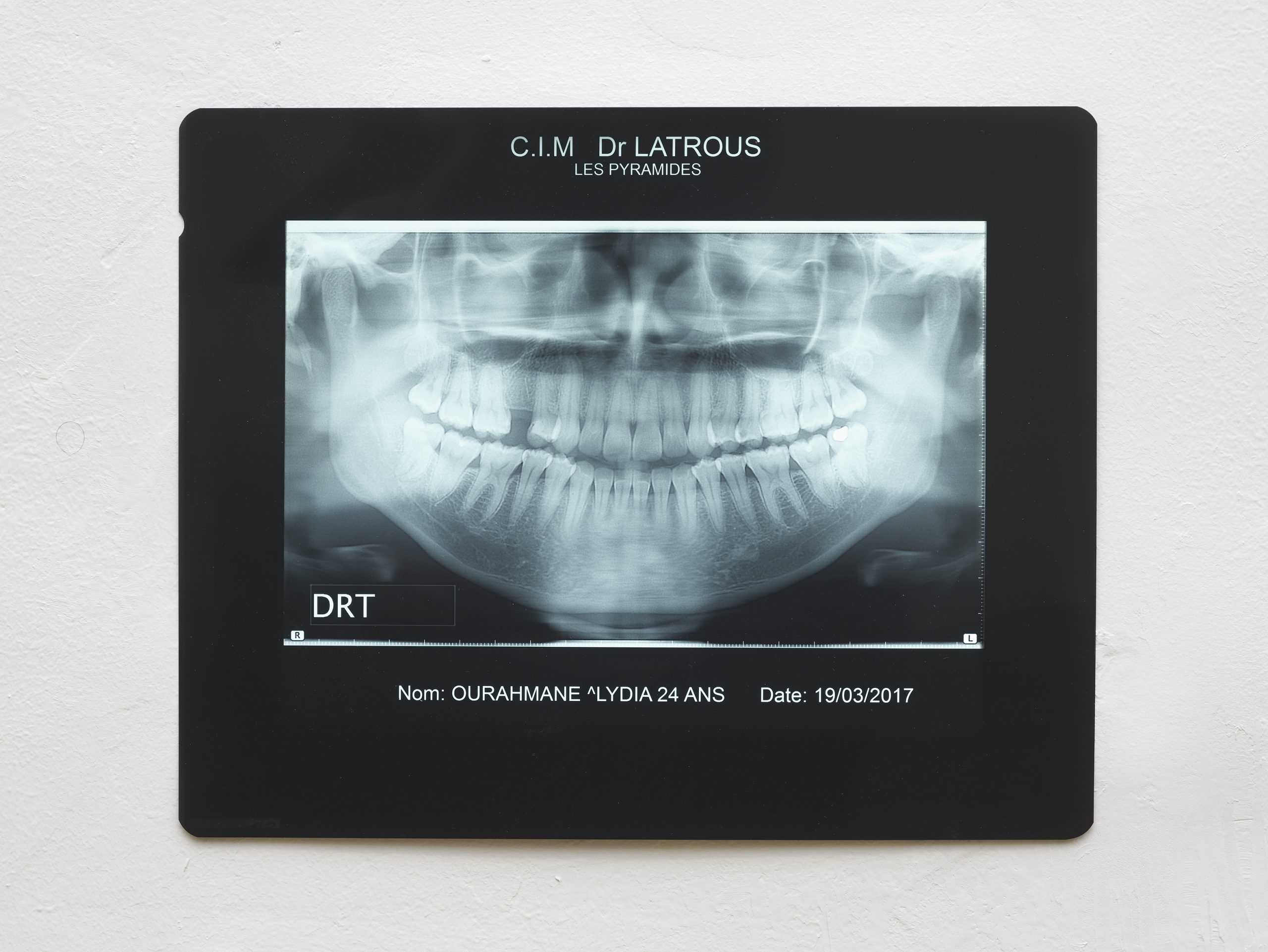

I’ll take you back to 2018, when I first saw your work “In The Absence of Our Mothers” at the Chisenhale Gallery. It was impressive how you managed to ‘project’ a personal or even localized trauma on a broader, collective level. I’m wondering if the gold tooth is still in your mouth.

Yeah, it is still there and making itself very present. It’s funny because the process or nature of that work has permanently altered my body. Of course, I knew there would be consequences; a foreign object with an imperfect shape was introduced into my mouth. Then there’s a tiny gap between that gold tooth and the tooth in front of it, causing some problems that I must fix now. But, like any gesture — it’s about the aftermath.

Let’s return to your most recent project, “Tassili,” shot in a Sahara plateau in Algeria. Not a single person is shown in the film, yet it’s all about the many forms of life previously known to thrive there. How did you decide to (re)visit such an off-limits location?

It’s actually no longer off-limits since the film was made. In December 2022, it was announced that they’ve opened the plateau to foreigners. You can fly directly to the closest airport, Djanet, and get a visa on arrival. So there is a monumental change taking place.

Last week, I met Ahmed at my opening; he is the guide who took us to the plateau when I made the work. There was so much bureaucracy in going there and getting the filming permission because nothing had been shot there before. The project was developed upon a collaboration between the Ministry of Culture and the Tassili National Park. Ahmed told me he recently took a group of Swiss tourists to the plateau. So the reality of that space has already changed significantly.

How do you feel that your work has managed to create that openness?

I don’t think it was me or the work. I can only speculate that through the project, they realized that the plateau could be safe to visit. I suppose the previous restrictions link to the fact that the region borders Libya, where tensions arose a few years ago. Journalists tried to come in and break stories about trafficking alongside it being a migration route between sub-Saharan Africa, the North, and eventually Europe. This frames the work differently in retrospect.

What if the landscape significantly changes due to human intervention from now on? Obviously, it can’t be visited en masse because you have to walk there, and only a few people can navigate the region. So it will remain relatively limited in terms of access. I’m thinking about the images we produced on the plateau and how they have now been reframed. These images may be the last of that space as it was.

It’s stimulating how artistic processes can activate such a chain of actions associated with landscape valorization… This show is also on view at Mercer Union in Toronto, while it has traveled to Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and Nottingham Contemporary, among other institutions. In which ways is the work informed throughout these different contexts?

For sure, you’re dealing with different audiences every time. While it has traveled to predominantly Western institutions, the perception, for example, in Algiers, was distinct because everyone knows what Tassili is, so it needs less contextualisation. But it was still met with the same kind of wonder as in New York, Toronto, Tunis, or Paris, where the audience felt like they were seeing these images of a place for the first time.

Our guide Ahmed was born on the plateau. When he watched the film, he was surprised by the definition of the images: they felt new like they could be anywhere, and at the same time, they felt familiar. He talked about the use of a Western electronic music score and how that oral juxtaposition superimposed a liberation of the images.

How about your upcoming exhibitions? Is there any new project you would like to share with me?

I’m preparing a show at Ordet, a Milanese space run by Edoardo Bonaspetti. Edoardo is also the artistic director of Fondazione Henraux, a marble quarry near Carrara. So when he invited me to exhibit in Milan, I immediately thought about the potential of that material. I’m particularly interested in contemporary points of weakness in the material created by methods of extraction. Where chunks are cut out of the mountain, the remaining material puts pressure on itself as it attempts to remain in place. So I am considering this fissure as a starting point.

PHOTO CREDITS

Photo: Jeano Edwards

Lydia Ourahmane, Installation view: Barzakh, Kunsthalle Basel, 2021, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Lydia Ourahmane, Installation view: Barzakh, Triangle – Astérides, centre d’art contemporain, Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 2021, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aurélien Mole

Lydia Ourahmane, X-ray scan, text, two 4,5g 18 karat gold teeth — one of which is permanently installed in Lydia Ourahmane’s mouth, Courtesy of the artist and Chisenhale Gallery, London. Photo: Andy Keate

Lydia Ourahmane, Tassili, 2022, 4K video, 16mm transferred to video, digital animation, sound, 46:12 minutes. Installation view: Lydia Ourahmane: Tassili, SculptureCenter, New York, 2022, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Charles Benton. Commissioned and produced by SculptureCenter, New York; rhizome, Algiers; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; Kamel Lazaar Foundation, Tunis; Mercer Union, Toronto; and Nottingham Contemporary.

Lydia Ourahmane and Yuma Burgess, Untitled (detail), 2022, Photogrammetry, generative adversarial network, polylactide thermoplastic, anodized steel, 56,9 x 269,2 cm. Installation view: Lydia Ourahmane: Tassili, SculptureCenter, New York, 2022, Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Charles Benton

Lydia Ourahmane and Yuma Burgess, Untitled, 2022, Photogrammetry, generative adversarial network, polylactide thermoplastic, anodized steel 56,9 x 269,2 cm. Installation view: Lydia Ourahmane: Tassili, SculptureCenter, New York, 2022, Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Charles Benton