Martina Bacigalupo and Sharon Sliwinski

Since your first collaboration with the NGO Human Rights Watch, Martina, your work has mainly taken place on the African continent. What led you to it?

MB: In 2007 I was offered a job as the photographer of the UN peace keeping mission in Burundi: it was supposed to be only for a few months, and I ended up staying there for a decade. As a white photographer, I quickly realized the ambiguous role that photography played on the continent, perpetuating the one-side narrative whereby Africa is a place of misery and violence and needs the West to get out of it. I thus started to question the very language of my expression, photojournalism, which flourished side by side with western imperialism and served it – directly or indirectly – for almost two centuries. Today colonialism as such does not exist anymore, but the underlying political relationships between dominant and subject societies are almost unchanged. This is what drives my visual research.

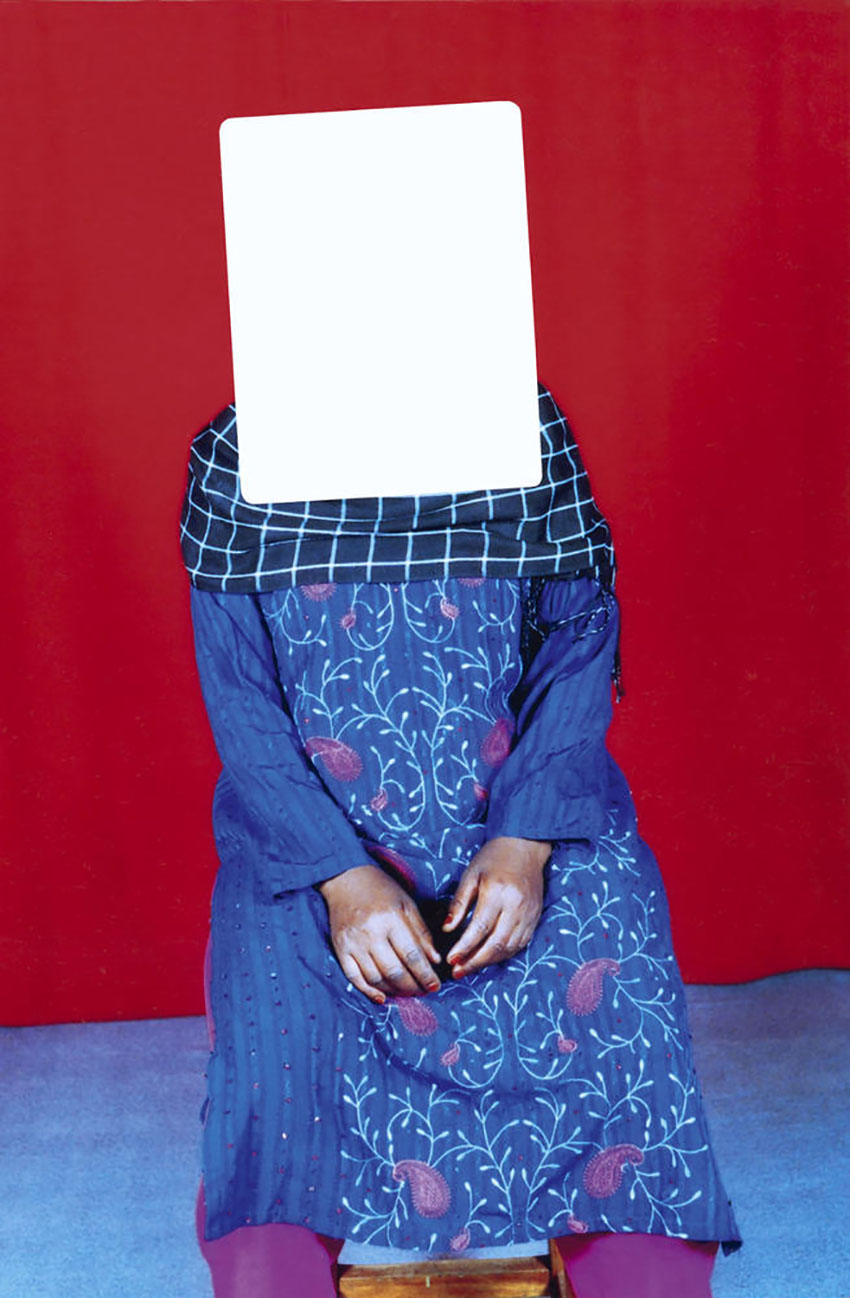

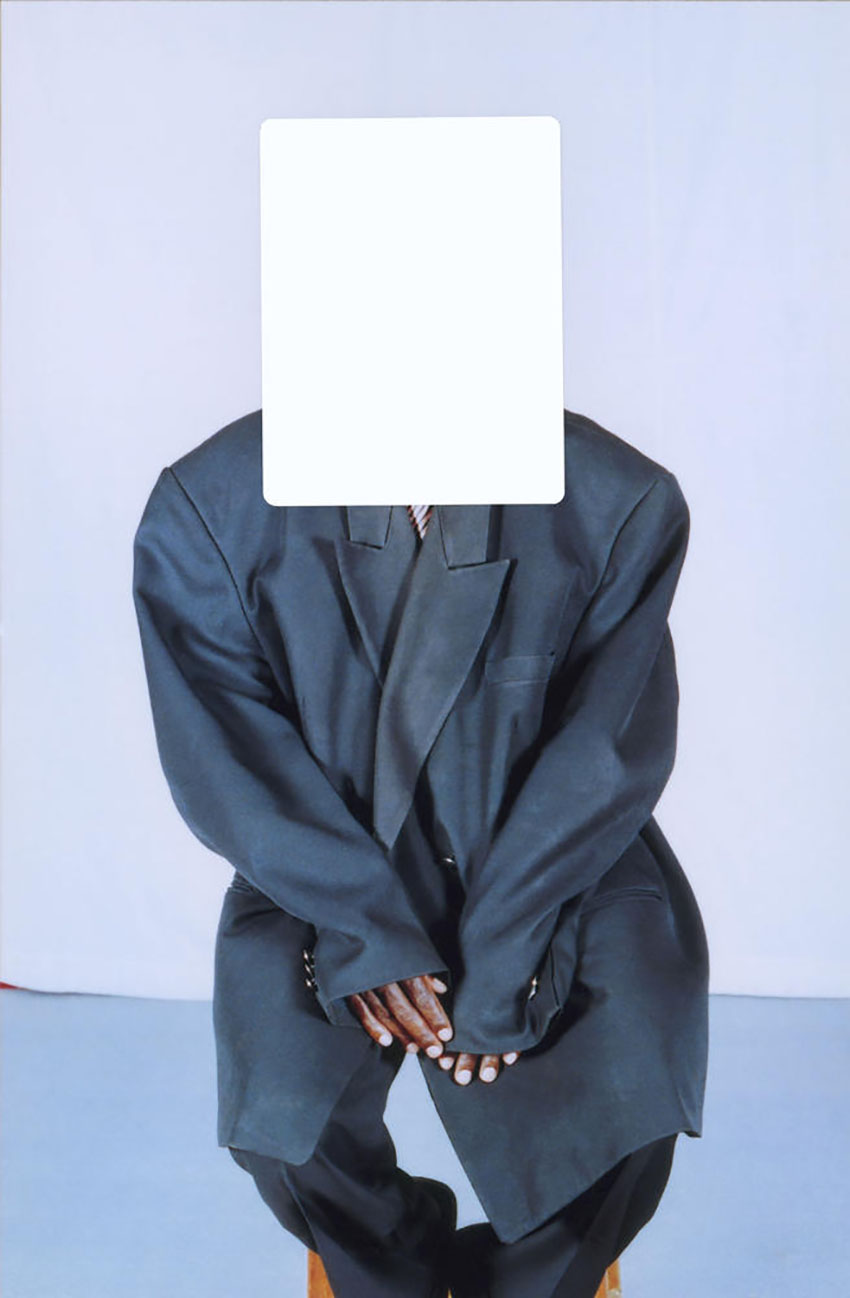

If we analyze your two projects, ‘Gulu Real Art Studio’ (2014) and the video ‘The Reverie Project’ (2018) created with Sharon Sliwinski, we notice a definite similarity. Is this really the case? On the one hand we find photographs with faces cut out, photos taken for identity documents, and on the other the silence of the migrants’ stories in front of the camera.

MB: I think that silence is indeed the common denominator of these two series. Silenced by an unjust system, these groups of people develop alternative ways of expression, which are often inaudible. Tina Campt describes the Gulu portraits this way in her book ‘Listening to images’: through “a quiet hum full of reverb and vibrato, not always perceptible to the human ear”, (…) these portraits enunciate quotidian claims to survival, resilience, and possibility in the aftermath of violence.”

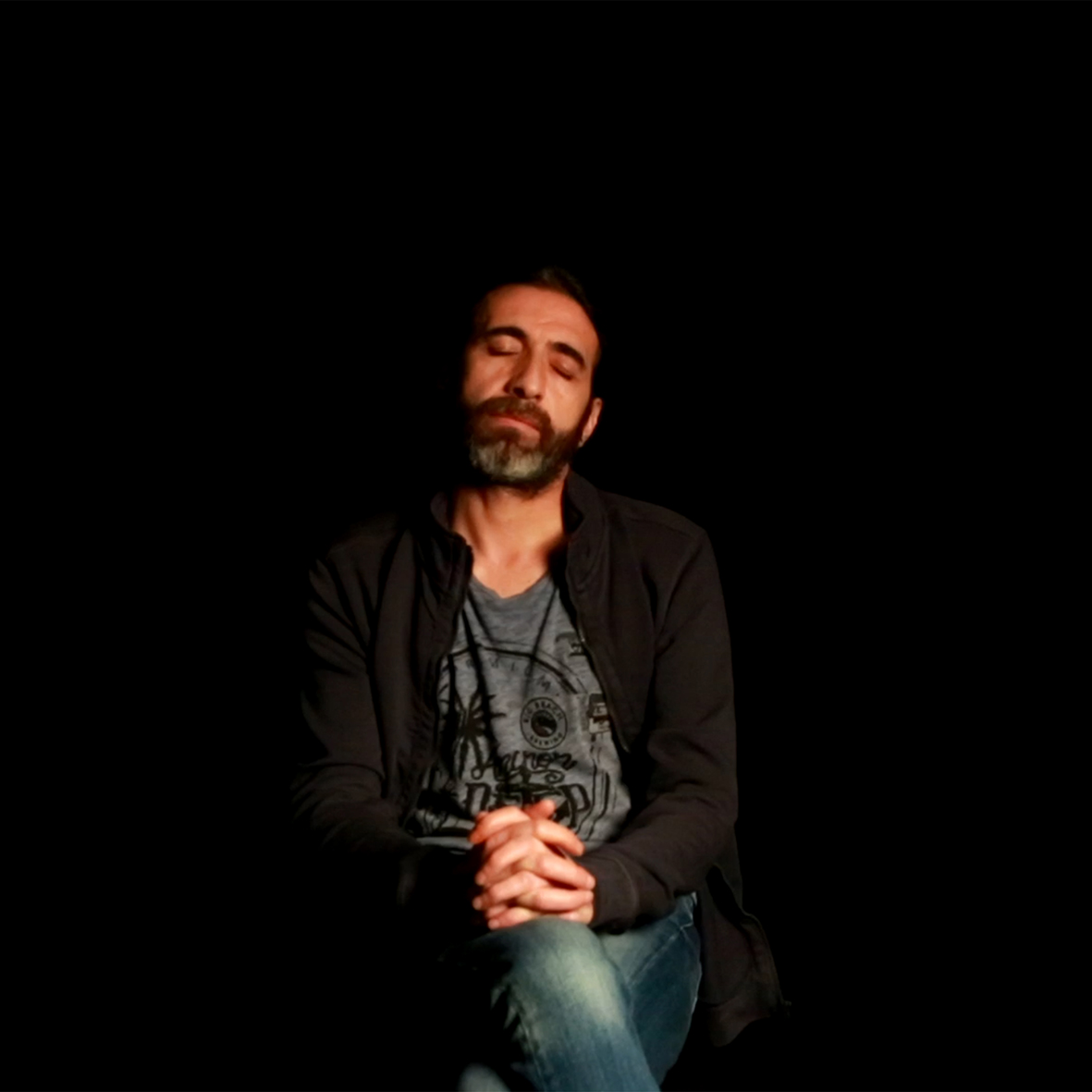

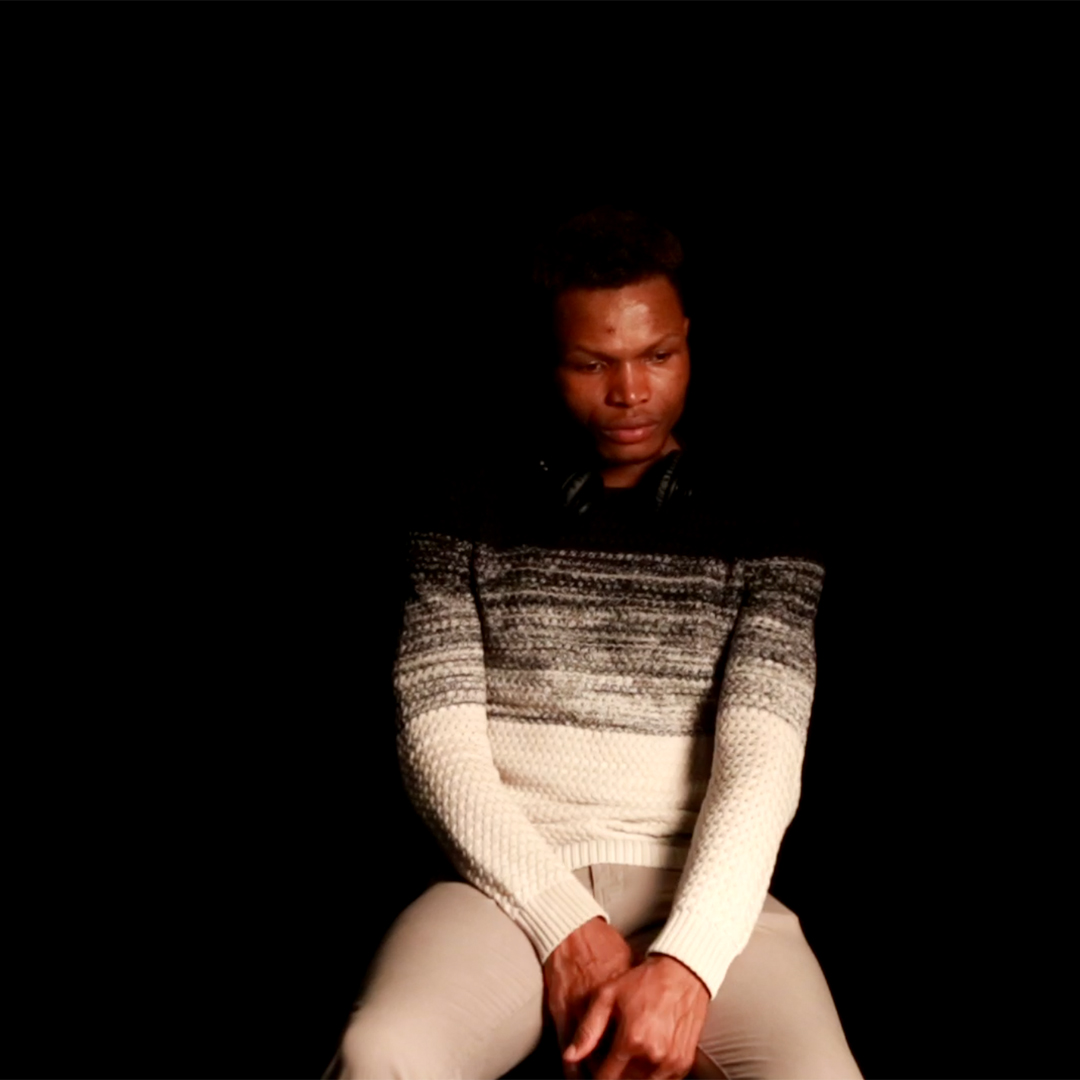

Silence as a fertile ground for the birth of resilience is also one of the funding ideas of ‘The Reverie Project’. We were inspired by the work of French neurologist Boris Cryulnik, who suggests the construction of new internal images is one step in the process of recovery from wounding experiences. Finding language and a community willing to listen is also necessary. We tried to make a space for this healing process. In both projects, silence is a proposition to refine our hearing skills, a kind of demand to find new ways to recognize the imperceptible claims to survival of people who have no right to speak.

How did you and Sharon collaborate on this project?

MB: Both Sharon and I have a human rights background. When we met, in 2017, we were investigating the politics of representation in photography, each from our own perspective, Sharon as a scholar and myself as a photographer. When Sharon was invited to do a project with the Human Rights Film festival in Geneva, she called me to see if I would be interested in collaborating with her.

At the time, the migration “crisis” in the Mediterranean was an omnipresent issue in the news and I had been working several times on the MSF rescue boat “Aquarius” operating at sea. The Film Festival put us into contact with a migrant center in Geneva called “La Roseraie.” After spending some time with the community, we decided to develop a project with them. Together with their help, we installed a photo-booth in the basement of the center and invited people to spend some time alone there. We didn’t give people explicit instructions. People voluntarily decided to try out the booth and we just turned on the camera and left people alone for 5 minutes. They were free to do whatever they wanted: talk, be silent, sit, walk around, or even leave.

After 5 minutes, we came back and asked people what had happened while in the booth. We really didn’t know what we would end up with and even considered the possibility that nothing would happen at all. Then the first participant came in. It was a Syrian gentleman in his 60s. When we came back after the 5 minutes, he told us that he had only cried 3 times in his life: the first when his mother died, the second when the Turkish police beat his son, and the third was that very day, in the booth. Sharon and I looked at each other and thought this was really not the effect we wanted the booth to have on people, so we were ready to end the project right there. But then the gentleman thanked us for the experience. Encouraged by his feedback, we carried on.

Some people told us that the 5 minutes where the first time they had experienced loneliness in years. A lot of memories came back in the booth. One participant told us he closed his eyes and suddenly saw his childhood village that he had forgotten. 35 people came in the boot for that project. Among them, migrants, volunteers, the director of the center and even ourselves. We wanted to overcome the power dynamics between the photographer and the photographed. We tried to remove the distinction between subjects and objects. To be honest, Sharon didn’t want to get in the boot that time. I am waiting for our second chapter to get her inside!

SS: It’s true, I was anxious to go into the booth. Anxious about where my thoughts would go. Collaborating with Martina is exciting for me because she pushes me to explore the uncomfortable places, which is, of course, where the most growth can happen – when you stretch beyond what is comfortable.

What also drew me to working with Martina was the way she was developing a practice that was collaborative, which was breaking down the tradition distinction between photographer and their subject. I learned a lot about collaborative practice from developing this project with her and the community at La Roseraie.

Why does your project refer to a “safe place for at least five minutes”?

MB: The photo booth we created was intended to be “safe” as in there were no questions to answers, no performance required, no stories to be told. It was just a place to be used for an intimate recharge. If people wanted to walk out of it, if they didn’t want to talk, if they didn’t want to show their faces, they could do so. It was free.

As per the duration, we had a long discussion about the time each portrait should last. Sharon thought 5 minutes was too much of an imposition on people. Although I understood her concern, I believed time was an essential element of the project. In fact, after a minute or two the tension or awareness of the camera falls and something between boredom, discomfort and reverie happens. It’s like an unconscious stream of thought, shared.

SS: One of the first things that a person loses when they become a migrant is their privacy. And the private sphere is, of course, where most of us feel safest. Part of what we were trying to do was to provide a safe place where people could be alone with their thoughts for a few moments – a temporary « room of one’s own. » Of course, there was a camera in the booth, so they were not entirely alone, but almost everyone who went in experienced a moment when they were able to lose themselves in their thoughts. We were trying to make a space that privileged this state of reverie – we wanted to create a place in which one’s thoughts were allowed to wander freely – and safely.

What did this experience leave you with? What do you think about the general attitude the Western world has toward migrants?

SS: Global audiences never seem to lose their appetite for images of distress. The international media feeds on images of people in states of extremis. The idea that these images can somehow galvanize human rights is a powerful fantasy. But in truth, the circulation of these images only serves the media corporations. This is not to say the documentation of atrocity is not important—it is—but we have enough evidence now to understand that human rights are not, in fact, secured by sharing these awful images. And, indeed, circulating them can sometimes further violate our sense of human dignity.

As Hannah Arendt made clear, the plight of the migrant is really the fundamental dilemma of the human condition, the task that all of us must face: finding a home in the world. And our sense of belonging—our very sense of reality, of existential vitality—is tethered to our capacity to give voice to our experiences, to put them into a shape that is fit for sharing with others. As humans we need to be seen and heard; we need our existence to be confirmed by others.

‘The Reverie Project‘ is our attempt to think through this tension: the need for a robust public theatre in which our experiences can be represented and confirmed, and, at the same time, our need to protect our “right to opacity,” to borrow Édouard Glissant’s beautiful phrase. I think this is one of our most urgent political tasks today: creating a shared political sphere in which people’s experiences can be witnessed and recognized, where we can confirm our mutual existence in a way that safeguards our dignity.

PHOTO CREDITS

Gulu Real Art Studio (2014)

The Reverie Project (2018)

Martina Bacigalupo

After studying philosophy and literature in Genoa, Martina Bacigalupo moved to Burundi, East Africa, where she worked for ten years as a freelance photographer, collaborating with magazines, foundations and international organisations.

Her work, which investigates the visual dynamics between Africa and the West, is part of several collections, including the Artur Walther Collection in Germany, the Donata Pizzi Collection in Italy and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, USA. In 2013, she published the project "Gulu Real Art Studio" with Steidl. In the past years Martina has developed with Canadian researcher Sharon Sliwinski "The Reverie project", an ongoing work questioning the representation of migrants.

Martina is part of Agence VU in Paris and runs workshops on documentary photography in France and abroad. Member of mentorship programs and jury member of international photography competitions, including the 2022 Oskar Barnack Award and the 2021 edition of World Press Photo, since 2018 she is Director of Photography for the French magazines XXI and 6Mois.

Sharon Sliwinski

Sharon Sliwinski’s work bridges the fields of visual culture, political theory, and the life of the mind. She has written extensively on photography, human rights, and the social imaginary - often using a psychosocial approach. She also works collaboratively with a wide variety of artists, scholars, and practitioners on a project called The Museum of Dreams. In this project among others, Sliwinski has created a space for exploring dream life as a crucial, if overlooked, way of seeing. Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Media Studies and the Centre for the Study of Theory and Criticism at Western University in Canada.

Current projects include 'An Alphabet for Dreamers: How to See with Your Eyes Closed' (under contract with MIT Press). Written for the general reader, this book provides a series of lessons about how dreams offer another way to see the world. Each of the short twenty-six chapters revives a dream from the historical record—from both the recent and distant past—to show how these experiences can represent, guide, and transfigure our most profound social conflicts.

Sliwinski also hosts a podcast series called 'The Guardians of Sleep'. The first season, which evolved out of a partnership with the Museum of London (UK), explores how the Covid-19 pandemic affected the dream life of people living in the British capital. The second season, now in production, explores both the colonial history of collecting dreams as well as contemporary Indigenous methods for attending the knowledge offered in these experiences. Sliwinski is also working on The Danzig Album, a book about photography, trauma, and transgenerational memory.

Martina Bacigalupo

After studying philosophy and literature in Genoa, Martina Bacigalupo moved to Burundi, East Africa, where she worked for ten years as a freelance photographer, collaborating with magazines, foundations and international organisations.

Her work, which investigates the visual dynamics between Africa and the West, is part of several collections, including the Artur Walther Collection in Germany, the Donata Pizzi Collection in Italy and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, USA. In 2013, she published the project "Gulu Real Art Studio" with Steidl. In the past years Martina has developed with Canadian researcher Sharon Sliwinski "The Reverie project", an ongoing work questioning the representation of migrants.

Martina is part of Agence VU in Paris and runs workshops on documentary photography in France and abroad. Member of mentorship programs and jury member of international photography competitions, including the 2022 Oskar Barnack Award and the 2021 edition of World Press Photo, since 2018 she is Director of Photography for the French magazines XXI and 6Mois.

Sharon Sliwinski

Sharon Sliwinski’s work bridges the fields of visual culture, political theory, and the life of the mind. She has written extensively on photography, human rights, and the social imaginary - often using a psychosocial approach. She also works collaboratively with a wide variety of artists, scholars, and practitioners on a project called The Museum of Dreams. In this project among others, Sliwinski has created a space for exploring dream life as a crucial, if overlooked, way of seeing. Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Media Studies and the Centre for the Study of Theory and Criticism at Western University in Canada.

Current projects include 'An Alphabet for Dreamers: How to See with Your Eyes Closed' (under contract with MIT Press). Written for the general reader, this book provides a series of lessons about how dreams offer another way to see the world. Each of the short twenty-six chapters revives a dream from the historical record—from both the recent and distant past—to show how these experiences can represent, guide, and transfigure our most profound social conflicts.

Sliwinski also hosts a podcast series called 'The Guardians of Sleep'. The first season, which evolved out of a partnership with the Museum of London (UK), explores how the Covid-19 pandemic affected the dream life of people living in the British capital. The second season, now in production, explores both the colonial history of collecting dreams as well as contemporary Indigenous methods for attending the knowledge offered in these experiences. Sliwinski is also working on The Danzig Album, a book about photography, trauma, and transgenerational memory.