Oscar Giaconia

January 2024

With his works, Oscar Giaconia creates an imaginary compost in which he portrays his mental obsessions, synthetic biologies and alchemical mutations, leading us through the linguistic meanders of the monstrous and the caricature, of metamorphosis and identities.

We shared some thoughts based on his suspended and hermetic figures, which are on show at the Fondazione Coppola in Vicenza until 24th January.

The exhibition The Kitbasher at the Fondazione Coppola climbs eight flights of narrow stairs that lead from the dark rooms of the first floors up to the compass of the Torrione, which dominates the city of Vicenza from its 40-metre height. What criteria did you use to select and distribute the works in such a peculiar context?

I have always had an occult fascination with the morphology of fortified places and architecture. Bunkers, crypts, taverns, dairy caves, cells and cellars are all part of that hypogean dimension that I call obsession.

I wonder, to paraphrase Derrida, if I have only one image, and it is not my own, and if some of them might have a congenital need for a chair or a dwelling. One might ask what that might be. The answer lies in the term “obsidereal”, a slippery and ambiguous word. On the one hand, it derives from ‘obsidere’, which means to hold the field, to sit in front; on the other hand, there are issues of siege and the active and passive obsessions that go with it.

In biology it has a double meaning, the philosopher Vincenzo Cuomo would say ‘viscous’, between invader and invaded, of organisms, especially plants, that invade an ecosystem after a military campaign.

I have not adopted any precise criteria other than to colonise the tower and the works documents it contains in a twisted and coiled way, more a twisted column rather than a tower. The tower thus becomes the habitat for the practice of a sadist who does nothing but build human trunks. A practice that I carry out from below, as if it were the leakage of a drainage pipe, an inverted core. If you were to fill a sea pit with a cast, you would get a termite mound

Between neologisms, onomatopoeia and glossolalia, I am struck by the titles you give to your works: CALABIYAU, KITBASHER, GINNUNGAGAP, AYE-AYE, HOYSTERIA, to name but a few. They are a mixture of exoticism and mystery. What is their genealogy and how do you relate the word to the image?

You give names only to defend yourselves from them. Each word is a polymer, a shape-shifting lamella. It is like a string of information that can be associated with the degree of organisation of a given material. I use this organisation to make it bask and overflow with everything that can pollute and disorganise it.

“The written word is already an image,” says William Burroughs: titles and various nominations are used as games and yokes, indescribable anomic names made up of amputations, transplants, splits, grafts and purges. Each title is a burning synthesis of stigma and behavioural symptoms that I embody and compel through my act of suffering.

The membrane that preserves the works and acts as a diaphragm between the real world and the work is particularly important in your work. Among the various types of supports, you use polyethylene and silicone alloys, protein binders, neoprene, nylon. They seem to become an integral part of the work and not just a container. What is the value of these showcases, as thresholds between the work and the viewer?

The work is a subject’s accomplice in its own agony. Every work and every operation associated with it becomes the object of experimentation with its own materials. There is an absurd continuity and complicity between what we polarise as organic and inorganic substances, metaphysically distinguished as alive or dead. Abiogenesis is the idea that life itself can be generated from inorganic chemical compounds.

I am staging a real synthetic biology: births as tests, samples, specimens. A macabre dance of hybrid polymers, a circulation of mobile states of matter to indulge in their unpredictable vermicular courses on the basis of decaying images. The decay of these substances is stubbornly and playfully kept alive. It survives by dissolving into other substances.

“When the image no longer speaks, it begins to go round in circles,” you said; a phenomenon similar to what cognitive psychology calls semantic saturation, i.e. when a word is repeated so often that it becomes detached from its meaning and turns into pure sound. With images, of course, different stratagems have to be used; in your case, the image is a sort of a bait, it is an anchor, as you yourself say, where a game of misunderstandings denies narrative and symbolism. Is the rejection of narratives and symbols your way of not going round in circles?

The sign is condemned to ‘tell’ other signs. There is no sign that is the source of the same. In the end, it cannot be a reliable witness. All that remains are the traces left by erasures and remakes, the ruins of which the images are the direct heirs. It is an apophatic and counter-technical path, where language is seized only to be disposed of. A language of sabotage.

I am making a phantom assembly kit for a blind pictorial war machine. I arbitrarily follow its assembly instructions, only to find that the machine system I have set in motion does not work. This malfunction not only interrupts the functioning of the circuit, but also generates a new pattern of intrusion: the strong desire to restore it according to a deferred and disjunctive logic.

The papers you use are a “shroud support”, as you define it. Biological processes and artificial technologies act on them as if they were (re)producing images in captivity. There is indeed an alchemical quid that characterises your work, but I also see a link with the abject as theorised by Julia Kristeva, that is, those parts expelled from the body that mark a division between inside and outside, between ego and non-ego, in order to isolate and remove the elements that threaten conventional identities and the order of the cultural system. Are you in any way interested in this relationship between the abject, the catharsis that results from it and the alchemical transformation?

Abjection is a passion-pulsion that coexists inextricably with its nemesis, apocatastasis. In Christian theology, it signified restoration and re-creation from an unclean, primitive and formless state.

Mysticism, mesticism, mastication and mnesticism are linked by what I see as an asceticism of closure. The more a work is closed and folded inside, the more it is subjected to slaughter and butchery from the outside.

The materials are subjected to treatments aimed at the expropriation of their respective properties (allodoxy): paper becomes cartilage, leather a polymer, silicone a membrane, wax a rubber, oil a gelatin, a sheet of paraffin film a flypaper, the mixture of a preparation on its support a polyphthalic slime; a substance that acts as a trace and memory of the form of its past, the construction of functional conditions for its own experience.

When dealing with a new material, what determines its behaviour is not necessarily its structure (bulk), but what happens on its surface. The monster is the skin, the monster is the surface. So we move from the ordnance of composition to the compost of conspiring materials, softly soft in a great mass grave.

PHOTO CREDITS

Oscar Giaconia, THE KITBASHER, veduta installativa presso Fondazione Coppola, Vicenza. ph. David Sarappa

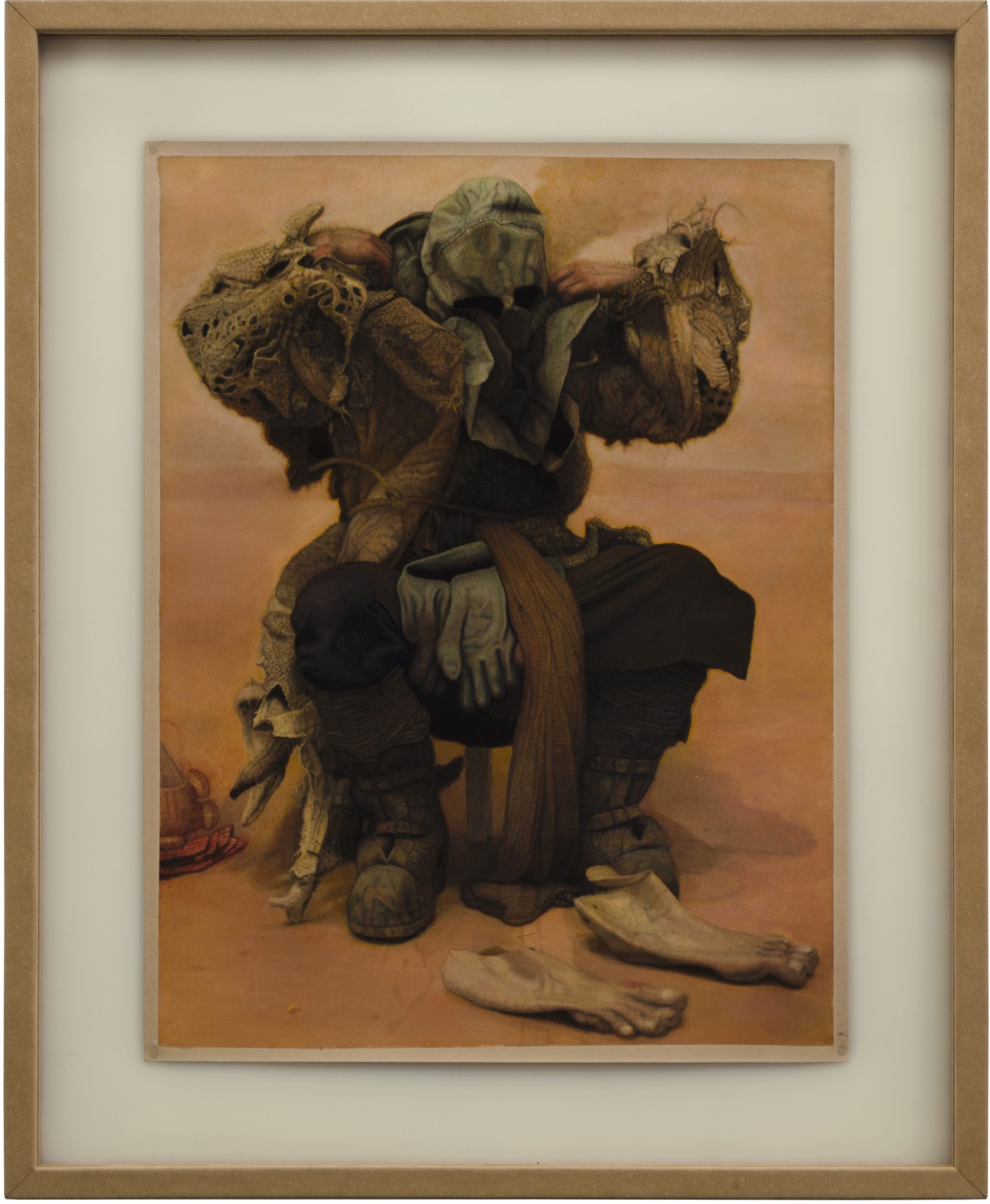

Oscar Giaconia, THE KITBASHER, 2019, olio su fibra cellulosica alla gelatina plasticizzata in teca di salpa e silicone. Collezione privata ph. Roberto Ferro

Oscar Giaconia, THE KITBASHER, 2020, olio su fibra cellulosica alla gelatina plasticizzata in teca di salpa e silicone. ph. Roberto Ferro

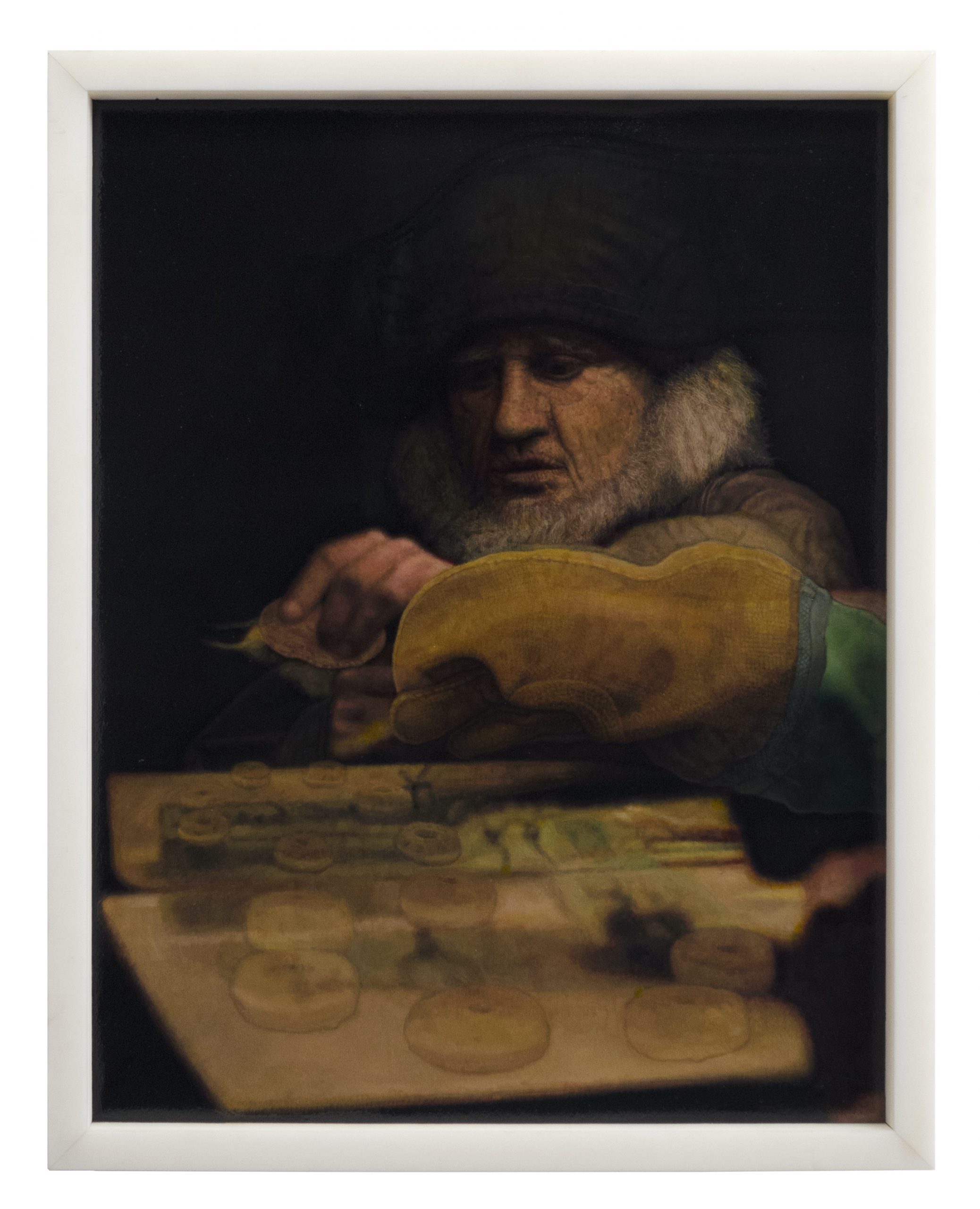

Oscar Giaconia, THE GRINDER, 2019, olio su fibra cellulosica alla gelatina plasticizzata e colla animale in teca di nylon. Collezione privata ph. Roberto Ferro