Features #25 - November 2023

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz - interview

PAULINE BOUDRY / RENATE LORENZ IN CONVERSATION WITH NICOLAS VAMVOUKLIS

“Walk Silently in the Dark Until Your Feet Become Ears.” The title of your new exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus is intriguing. Can you tell me how it relates to the exhibited works?

For us, the title beautifully conjures the transformative power of movement and, more specifically, of bodily movements in concert with others. We imagine the silent walks in the dark as a practice that reshapes the moving bodies, their rhythms, and their relations to the environment. This specific phrase is taken from the instructions for a deep listening exercise by composer and electronic musician Pauline Oliveros, whose work has always been an important inspiration.

Its centerpiece, the film installation “Les Gayrillères,” explores the right to be opaque and control one’s visibility. Could you elaborate on this idea and its significance in today’s context?

For the film, we connected the concept of opacity to dance movements. We worked with five choreographers/performers, and all the stage lights were fixed on their costumes. With their arms, legs, and heads in motion, they shed light on others and themselves. Their next move or gesture might take all the light away and go on in the dark. Together, we created a choreography where the movement of bodies and light produce an interplay of concealment and exposure.

We had learned in our leftist upbringing that becoming visible is the precondition for gaining rights, which might be true in certain situations. Still, we are troubled by the experience that visibility might not work out for everyone. Some of us have always been rendered hyper-visible; we have been searched, researched, surveilled, or visually oppressed in different ways. If you have ever needed to disappear from view, you might be very familiar with the urge for opacity, a concept that the author, poet, and activist Edouard Glissant has coined. For him, opacity is a useful strategy in colonial struggle. More generally, it is a precondition of the ability to live without being categorized or measured and to have the right to difference. Embracing difference, engaging in collaborative work, and controlling one’s visibility by masking and uncovering, are also some of the essential politics that queer cultures have nurtured. We like how, in the film, the individual disappears in the dark, and the arms, legs, eyes, or hair remain there in short moments of collective shine.

The film draws inspiration from Monique Wittig’s feminist novel “Les Guérillères.” What narrative are you trying to convey through this reference?

Monique Wittig’s book puts the finger on the connection between masculinity and war by inventing a word that mixes guérilla and the feminine form of the French word for warriors, “guerrières.” Wittig’s work also does not shy away from taking aggression and violence seriously while sketching ways of living together differently. Her book imagines a fierce group of feminists/lesbians who oppose the idea of individual heroism and move together in their own time.

In our film installation “I Want,” which takes up material from Chelsea Manning’s disclosure of war atrocities and Kathy Acker’s de-individualizing aesthetic strategies, we already worked on similar ideas, bringing together resistance against war, the question of gender, and trans-activism.

The title “Les Gayrillères” opens up Wittig’s wordplay again, transforming the idea of war altogether into the collective rhythm of a queer crowd. This crowd is situated in a world where visibility is risky, and transformation is a difficult maintenance work of performing tasks in an ongoing repetition.

The exhibition also includes sculptures that choreograph the relationship between on-screen and off-screen, sounding and listening. In which ways do they enhance the visitor’s experience and engagement?

These sculptures are all connected to performance. They are made of wigs and chains – both often appear in our films as props or costume parts – or microphones and used dance floor pieces, which still bear the traces of past performances. They all inhabit the liminal space between being an everyday object, a prop, or a sculpture; they seem to have directly stepped down from the film into the exhibition space.

For creating those objects, we choose materials that orchestrate crossings between different worlds. Chains are used for binding or as jewelry. Microphones are employed for playing music or amplifying protests. Smoke is utilized for hiding bodies in clubs or highlighting one’s presence at demonstrations. We occasionally speak of the props as additional performers; in our films, they often move independently of bodies. In the Oslo exhibition, they might also be seen as a group of additional performers, still backstage, warming up for a performance, which is not yet happening.

Can you share more about the collaborative process with your performers, who are choreographers, artists, and musicians?

We never cast performers; we like to work with people whose practice we enjoy and admire. We want to engage in an ongoing conversation about aesthetics, politics, and life practices. We also work with the same film team as much as possible. For instance, Bernadette Paassen has been our DP for years, and for sound post-production, we have always worked with Rashad Becker. In “Les Gayrillères,” we asked Julie Cunningham and Harry Alexander to produce a choreographed sequence that all dancers could perform, and we started to work on the overall choreography from there. Usually, we meet with the performers, bring some ideas and images, and begin with improvisations that we consistently record. We look at the footage, select those parts that work for the camera, and then try to make them more precise in the next session. From there, we produce a film sketch that is our film storyboard for the shooting. But we love failure and coincidences, and often, our plans go overboard to something that we didn’t foresee, which is much better than all we had carefully planned.

“Les Gayrillères” is part of a film trilogy, along with “Moving Backwards” and “(No) Time,” which have all been presented in prestigious venues worldwide. Can you discuss the overarching themes between these three parts?

We are showing all three works together in one place for the first time, at this moment, at the Bienal de São Paulo. They all focus on dance and queer temporalities in various ways.

“Moving Backwards,” the first installation we initially made for the Swiss Pavilion of the Venice Biennale in 2019, works with a camera that relentlessly moves from right to left and left to right at the same speed. Its movements are doubled by an automatic curtain of shiny sequin material. Some walks, solos, and group dances are carried out backward, while others are digitally reversed. For example, dancer Marbles Jumbo Radio learned to dance one of his creations backward. Then, the filmed sequence was again reversed in post-production. Sometimes, only the music was reversed. All of this creates doubt and temporal ambiguities for the overall installation. You somehow never know if you see the past or the future of a movement.

In “(No) Time,” we have dancers performing in two different timescapes simultaneously; for instance, one performs very fast and one very slowly in the same scene. There is suspicion whether the movements can be credited to the performers’ ability or if they are done in post-production. The automated movements of a revolving door and blinds going up and down produce a rhythm on their own.

All three installations operate with dancers/performers who come from very diverse performance backgrounds, such as postmodern dance, street dance, and drag performance.

PHOTO CREDITS

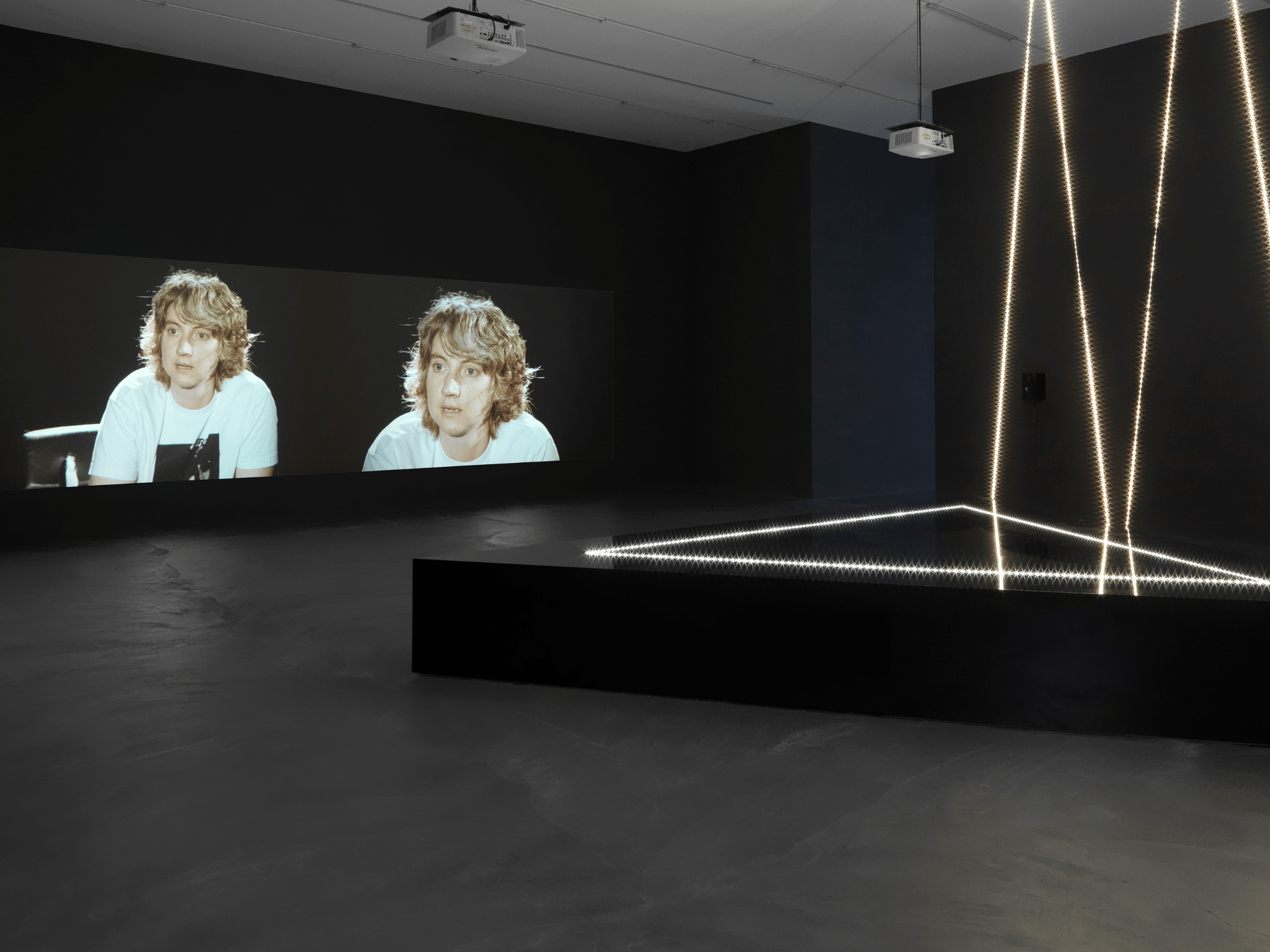

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Les Gayrillères, 2022, Two-channel video installation. Installation view: Walk Silently in the Dark Until Your Feet Become Ears, Kunstnernes Hus, 2023 Choreography/performance: Harry Alexander, Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Nach, Joy Alpuerto Ritter, Aaliyah Thanisha. Gayrillères choreography: Julie Cunningham and Harry Alexander Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam Photo: Annik Wetter

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Les Gayrillères, 2022, Two-channel video installation

Installation view: Walk Silently in the Dark Until Your Feet Become Ears, Kunstnernes Hus, 2023

Choreography/performance: Harry Alexander, Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Nach, Joy Alpuerto Ritter, Aaliyah Thanisha. Gayrillères choreography: Julie Cunningham and Harry Alexander

Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Photo: Annik Wetter

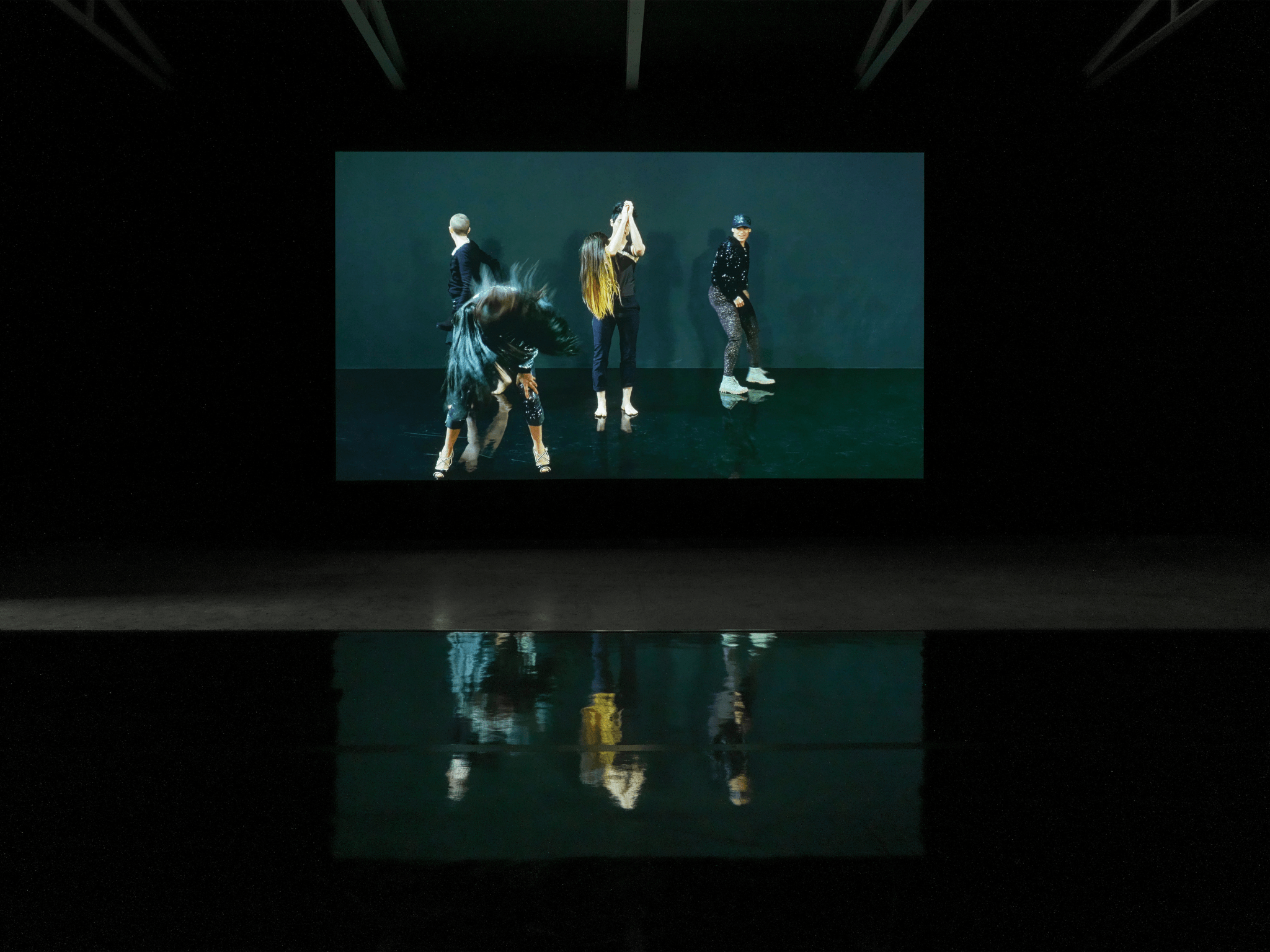

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Les Gayrillères (film still), 2022, Two-channel video installation

Choreography/performance: Harry Alexander, Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Nach, Joy Alpuerto Ritter, Aaliyah Thanisha. Gayrillères choreography: Julie Cunningham and Harry Alexander

Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Les Gayrillères, 2022, Two-channel video installation Installation view: Walk Silently in the Dark Until Your Feet Become Ears, Kunstnernes Hus, 2023 Choreography/performance: Harry Alexander, Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Nach, Joy Alpuerto Ritter, Aaliyah Thanisha. Gayrillères choreography: Julie Cunningham and Harry Alexander Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam Photo: Annik Wetter

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz

Exhibition view: Walk Silently in the Dark Until Your Feet Become Ears, Kunstnernes Hus, 2023

Photo: Annik Wetter

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, I WANT, 2015, Two-channel video installation

Exhibition view: Portrait of an Eye, Kunsthalle Zürich, 2015

Performer: Sharon Hayes

Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Photo: Annik Wetter

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Moving Backwards, 2019, Video installation

Installation view: Swiss Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2019

Choreography/performance: Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Latifa Laâbissi, Marbles Jumbo Radio, Nach.

Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Photo: Annik Wetter

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, (No) Time, 2020, Video installation

Installation view: Rennes, 2021

Choreography/performance: Julie Cunningham, Werner Hirsch, Joy Alpuerto Ritter, Aaliyah Thanisha

Courtesy of Marcelle Alix, Paris; Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz

Photo: Bernadette Paassen