Pedro Reyes in conversation with Elisa Carollo

The works on view are part of the series Disarm which creatively repurpose and playfully reactivates remnants of weapons that the Mexican army had collected and destroyed. There are many socio political comments, that can be associated to this work: as you often did, you have applied the same aesthetic of shock approach as surrealists to create paradoxical juxtapositions between “negative” objects brought into an entirely differently collaborative and positive context turning arms into instruments, part of a new army orchestra to just create music and generate aesthetic sensations. A witty, provocative but extremely engaging artwork, to address the reality of wars and arm violence that is still very topical, all around us. Can you tell us more about what inspired this work, how you came to it, and in particular this idea to be able to use arms to create a community, instead of dividing?

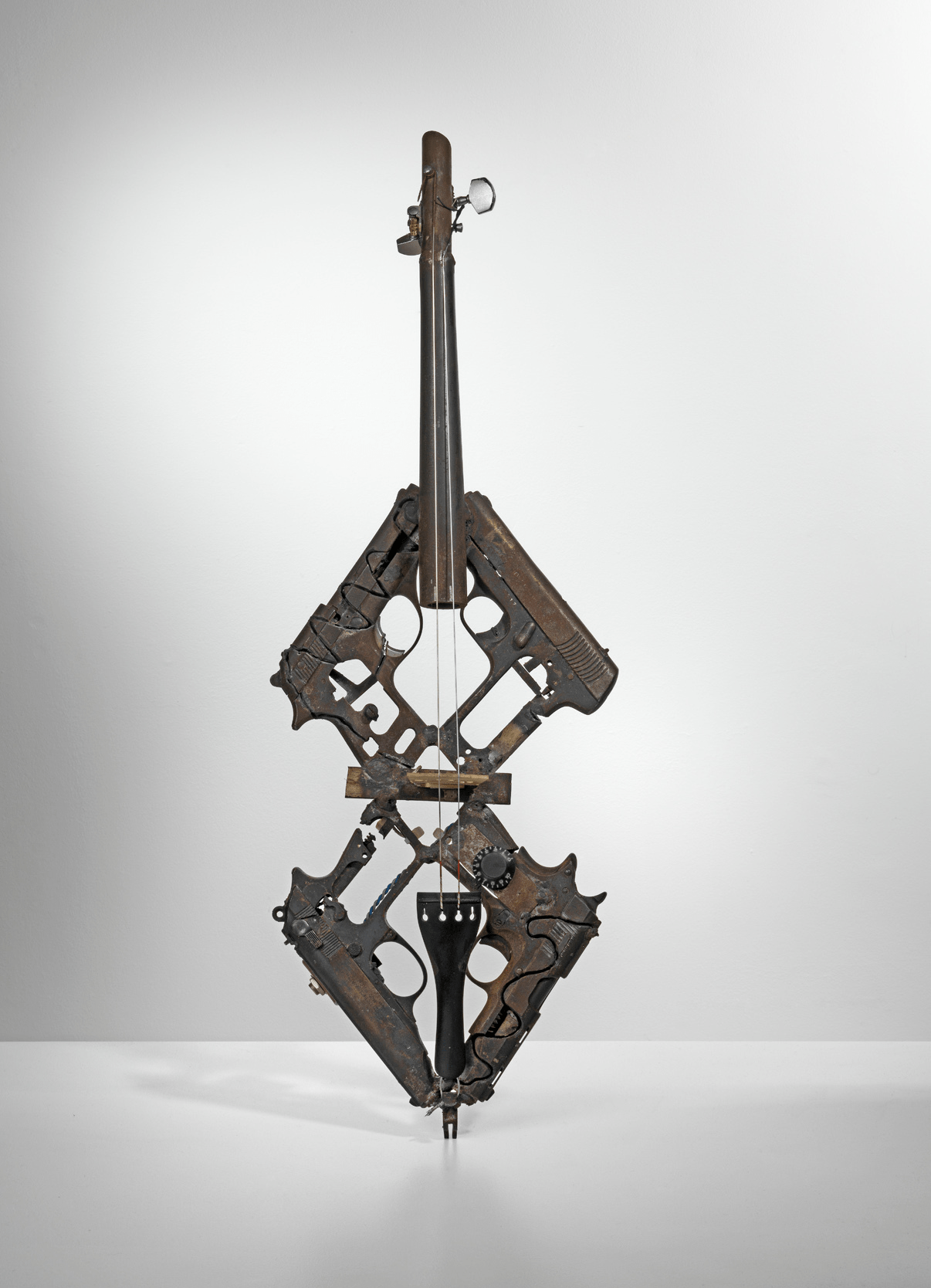

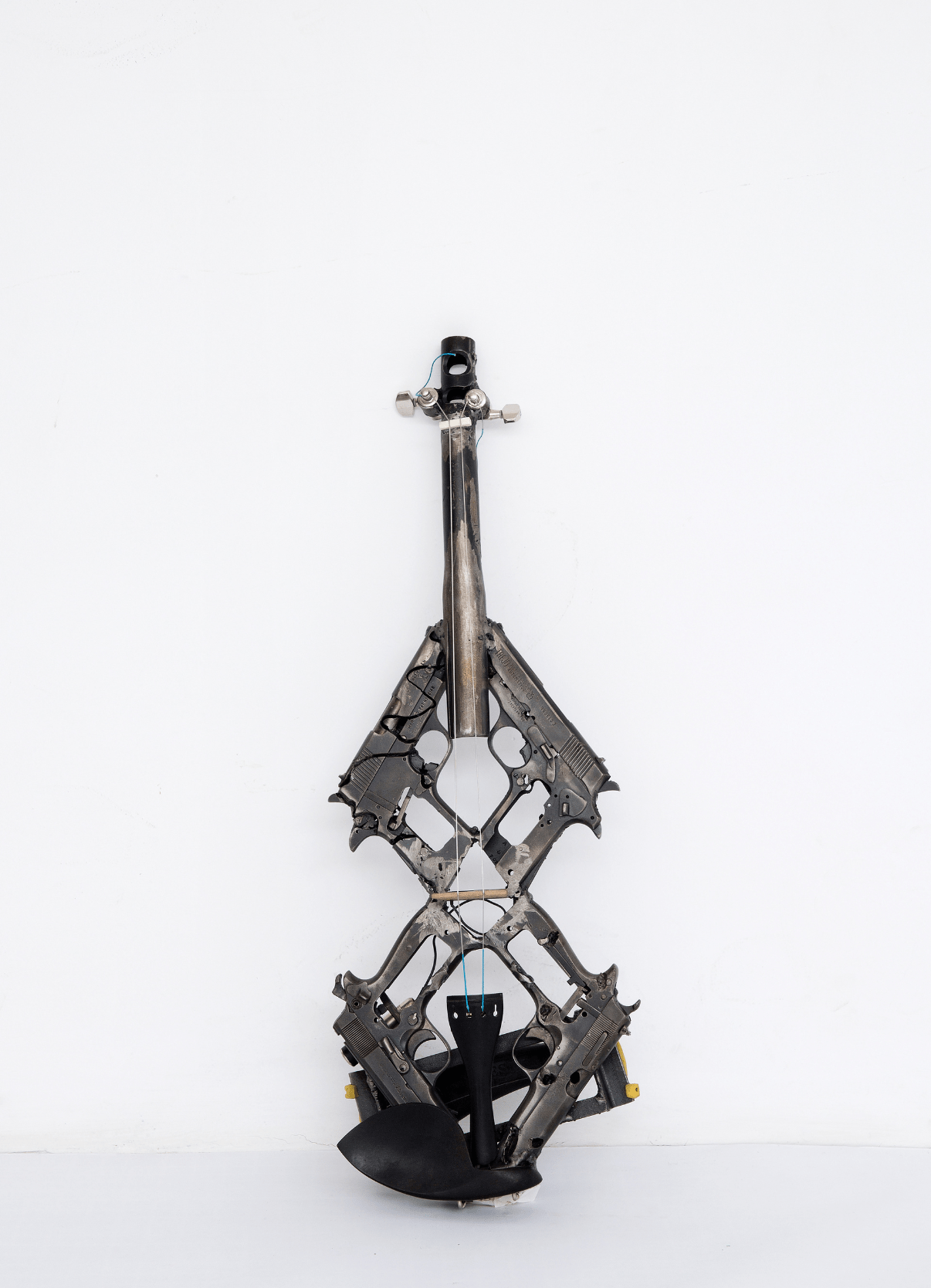

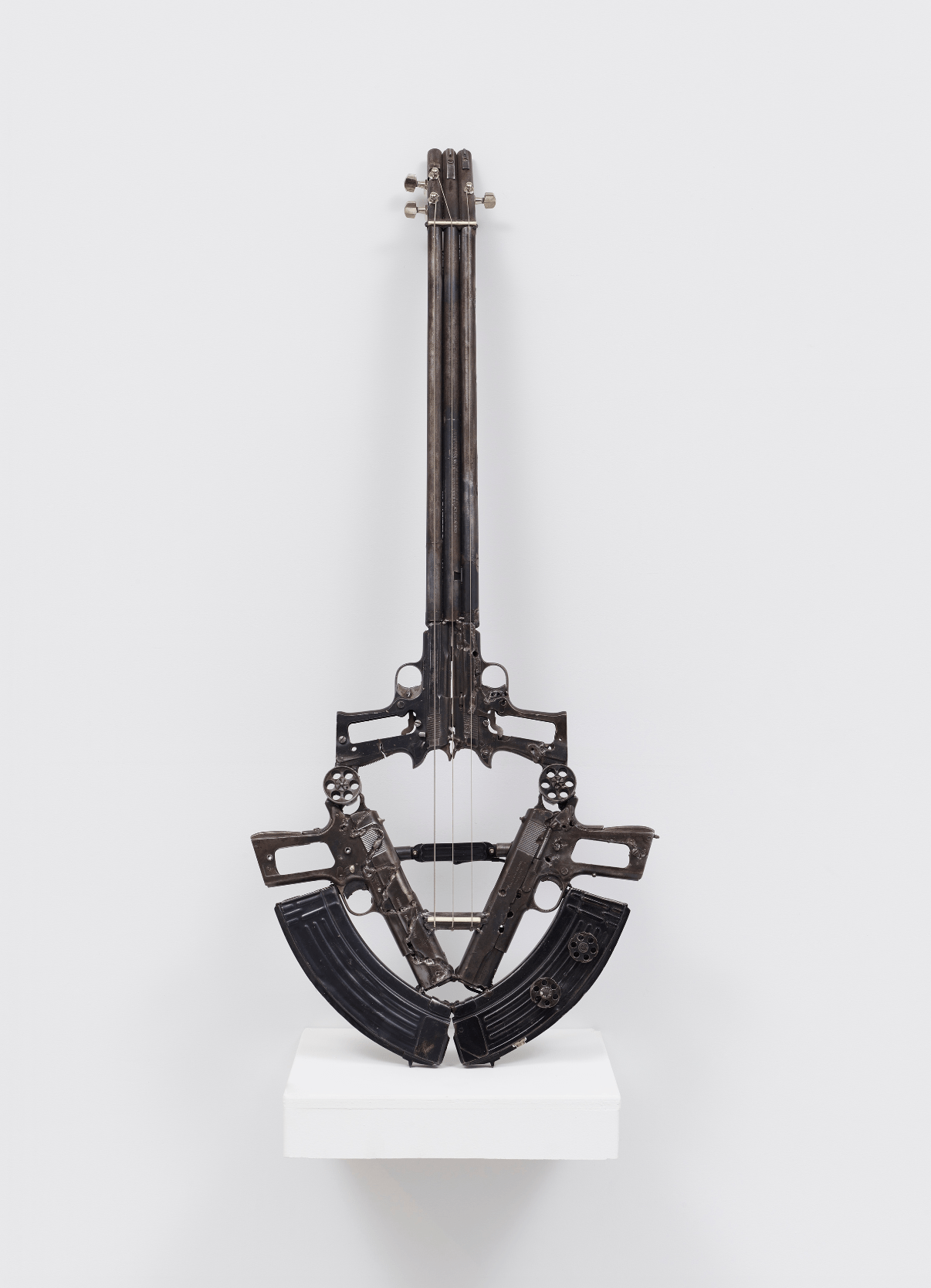

Disarm aims to be transformative not only in the physical sense but also in a psychological and social domain. Weapons have a power which is by definition overwhelming but here they can be found defeated by the artistic process, the metal that was engineered to kill is now producing music. We have to approach this a bit as cavemen, taking gun parts and scratching, blowing, reeling and creating different arrangements to extract sounds from the steel. For me this is an alchemical process, in alchemy you work with the nigredo, the dark matter, that’s why this attempts to turn shit into gold, turning weapons into music. Weapons represent our dark side, our drive to kill, and music is the opposite, it’s the universal language accessible to everyone. I like the idea of this change of polarity where the same metal has been used for an opposite version for what was originally intended.

Since the Sanatorium, 2011, your work has often taken the form of social experiments, and social tools, to activate communities and guide them first to more intimate and personal resolutions and realizations, and most recently to more universal topics regarding the society and the world at large. Interestingly and in contrast with other more activist artists practice, you generally avoid any purely aggressive or subversive approach, preferring works that encourage interaction, participation and sometimes even co-creation with the viewers. We are living in a time of hyper media exposure to different info and images that make people desensitized, often not being able anymore to distinguish the “tragic” from the obscene and so totally disconnected from the tragedies happening in our world, which always seem so remote and “other”. Why and how do you believe that this more hopeful and positive approach to the audience can leave deepest marks and effects on people, to raise awareness but also encourage action?

I believe that art can be a form of catharsis, catharsis in Greek means purification which is to expel a toxic substance out of the body. Sometimes art can be violent, I’m not against that, I think is good to have movements of symbolic violence because a violent act framed in the context of an art project can substitute the need to carry out those violence acts in real life, however it is important that there is a processing or afterthought to make sense of violence. In the case of working with weapons I had to be very careful because if it’s not done correctly it could glorify o romanticize the very thing that we try to stigmatize, so that’s why I am very much concern that the transformation is meaningful, a musical instrument is precisely that, an instrument, which means that is something that can be used to produce new pieces of music, so there’s a double creation, one when the instrument is created and the second one when the instruments are performed which is already like a life affirmative process.

With a similar approach, you also started your most recent project (and huge challenge) aiming at raising awareness on the Nuclear danger. This project turned your art into a large global campaign, operating between art installations and activations around the world, collaborative actions and exhibitions, as the monumental inflatable Zero Nukes, 2020, presented first in Times Square in New York City, and then all around the world. Can you tell us more about your approach in this project/campaign and why you decided to focus on the nuclear threat – which of course has been one of the biggest but often less mentioned danger and silent war between countries for years now, and the competition/conflict is just worsening over time.

Preventing nuclear war should be the number one priority in the planet, yet is a cause which receives no attention, there is an important activist community but is relatively small if we compare it with other causes, so to support the urgent work that this organizations do there is something art that can do to help and is to translate this messages. In particular, nuclear disarmament is an abolitionist approach, not to curb nor to stop the production of nuclear weapons but to also eliminate every single one of them until there is zero nuclear weapons. The same way that we have banned biological weapons, chemical weapons, landmines, the most dangerous of all which are nuclear weapons should be canceled completely.

So in order to convey this concept I decided to focus on the concept of Zero and I made an exercise in translating the word “zero nuclear weapons” into every single language I could find, which led to Zero Nukes slogans placed in different supports such as inflatable sculptures and pickets.

The research on nuclear weapons has also generated the video Under the Cloud, 2023, produced for your exhibition at the Santa Fe Museum, and which we have the honor to premier in Europe. The video engages in an highly critical investigation of the gigantic project of new production of nuclear weapons in US, and how those investment are often legitimized across the world to the public opinion as research in alternative energies, while there is instead a clear threat not only in terms of a potential conflict that could destroy the entire planet, but also in terms of current effects and the dramatic impact on both the territories and the local populations where those technologies, and weapons, are developed and tested. Can you tell us more about this project, how it was generated, how you produced it, and why it’s so urgent to openly address those issues today?

I’ve been working on the issue of nuclear disarmament since 2013 but most intensively from 2019 were the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists commissioned me Amnesia Atomica, as the Bulletin says “we are 90 seconds to midnight”, meaning that we’ve never been closer to experiencing nuclear war ever in human history. I made “Under The Cloud” with the downwinders from New Mexico. Communities that have been affected by nuclear testing but also uranium mining, which made my position a bit more radical since I was first after nuclear weapons and now mistrust also nuclear energy, I just don’t trust mankind with anything radioactive. The urgency of nuclear disarmament is the only alternative to armageddon and also has to do with breaking down the myth that nuclear weapons make you safer. Once you’re aware of these, it is very clear that nuclear energy is not clean nor green, the permanence of radiation for a thousands of years and the impossibility to keep leaks or accidents or explosion under control is impossible, this shows how important can be to see things from the perspective of indigenous world view.

PHOTO CREDITS

Pedro Reyes, Goodoo, 2011 – present.

Exhibition view, MAAT Lisbon, 2021. Photo: Vasco Stocker Vilhena

©Pedro Reyes and MAAT

Pedro Reyes, Disarm (Violin XII), 2016

Repurposed weapons

60 x 21 x 11 cm

©Pedro Reyes and Lisson Gallery

Pedro Reyes, Disarm (Guitar), 2016

Repurposed weapons

90 x 40 x 7 cm

©Pedro Reyes and Lisson Gallery

Pedro-Reyes, Sanatorium, 2014

ICA Miami

©Pedro Reyes and Lisson Gallery

Pedro Reyes, Zero Nukes, Installation view, Times Square, New York City, 2022

Photo: Pedro Reyes

©Pedro Reyes

Pedro Reyes, Zero Armi Nucleari, Exhibition view, Museo Nivola, 2022

Photo: Andrea Mignogna

©Pedro Reyes