Where things happen #20— December 2023

The essence of the work of Sanié Bokhari lies in a fluid limbo, that of living a double identity as an artist born and raised in Pakistan, then moving and working in the States.

For this reason, the characters of her works often float in a liquid space, suspended between time and place, between memories and hallucinations of a far away place, that is still very much a part of her imaginary and cultural language.

But it is from a porous space in-between that the artist is able to channel a unique perspective of her life and identity in both Pakistan and the States, today, questioning the traditions she left behind, but also appreciating and appropriating elements, from afar.

When we met over the Winter holidays in her studio in Brooklyn, Saniè had just returned from another trip in Pakistan, skipping the Miami art week circus, and going back instead to her hometown and family.

Sanié Bokhari moved to the US for grad school, obtaining a MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design, afterwards she decided to stay.

After working for an artist for a while and spending a period back home with the pandemic for Visa issues, Saniè is now persuaded that New York is the place to be for her, for now, to fully explore her practice.

As she shows me some previous works, I can acknowledge how her artistic practice has evolved quite rapidly over the last year, reaching a very specific and consistent visual language that is at once intimate and personal, historically grounded, and universally interconnected with the broader cultural and visual history of her homeland.

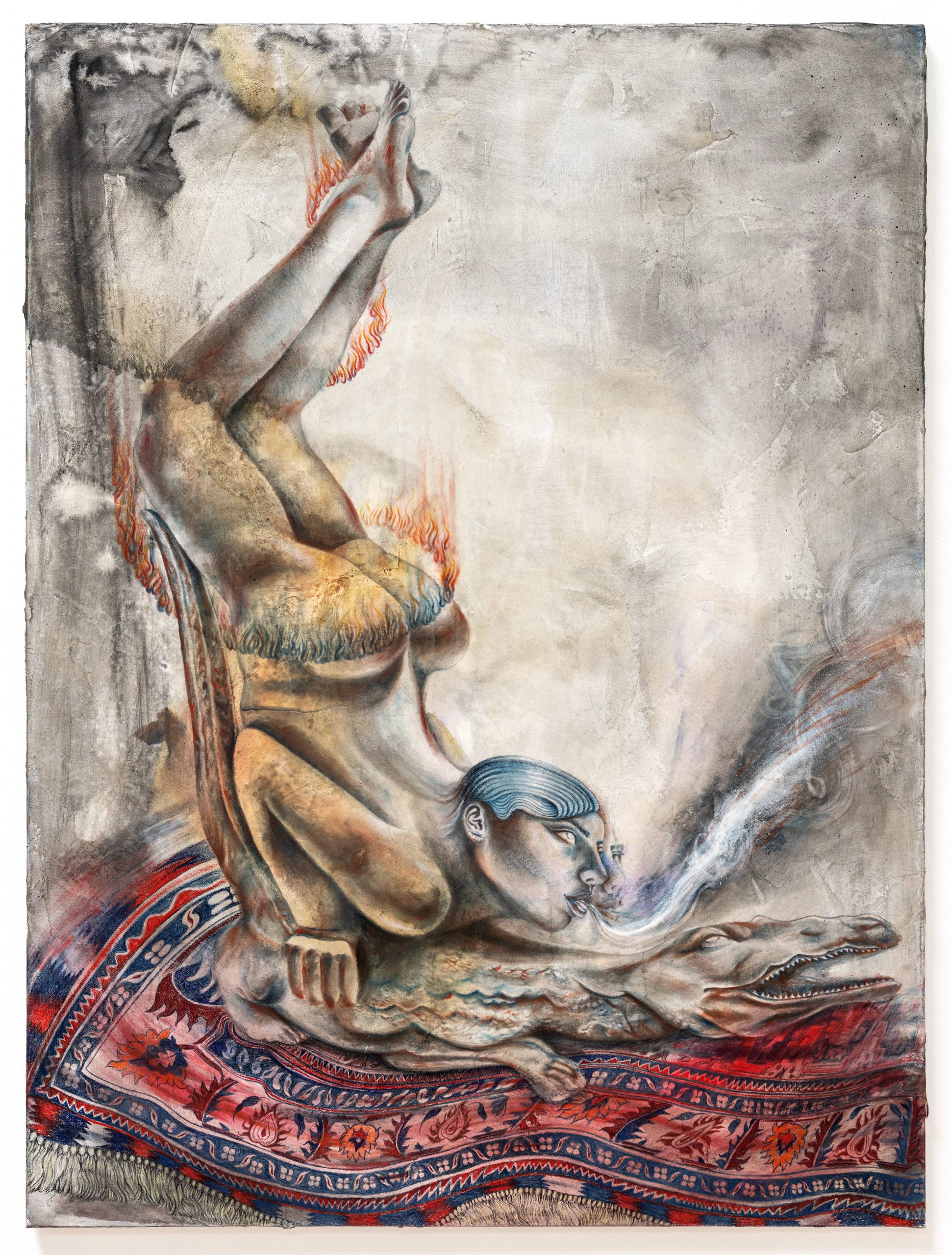

Working now mostly on canvas and works on paper, Saniè has formulated a contemporary interpretation of ancient miniature paintings: the graphic style made of sinuous lines is still present and, as she admits, a big source of inspiration for the elements and symbologies she incorporates, much of which deriving from books of ancient South Asian and Pakistani mythological and religious narratives.

At the center of the scene, however, Sanié depicts sort of alter egos of herself: female figures often engaged in meditative expressions, as they roam in their spectral presence between a mental and spiritual realm, already beyond any physical reality.

The luring use of the color palette adopted is also quite evocative: primarily based on gray graphite tones, deep blue and a just recently introducing reds, these colors function both as connectors with her homeland scenery and traditions, and at the same time allow an abstraction of the scene that leads them into other dimensions.

The gray of the graphite, as the artist explains, immerse these scenes in the same foggy atmosphere she experiences everytime she lands in Pakistan, due to the current dramatic levels of pollution that turns the urban landscape into a confused series of shadowy and nebulous presences.

The newly introduced reds bring the works instead to a more passionate reality of the female body – something that she was able to more openly explore only in the US.

Finally, the blue transfers these scenes into a more fluid subconscious, memorial or dreamy dimension, in a space between places and moments.

As Saniè explains, she adopts a very specific blue pigment she found in her travels to Morocco, which adds a melancholic tone to the work. This blue is similar to the one used by Picasso in his blue period, which fascinates and largely inspires her. She confesses that, when she finally visited the Musèe Picasso in Paris and saw an entire room of blue period paintings, she had a fulguration: these blue tones that seem so timeless and universal and the melancholic characters of these paintings spoke to her.

All of Sanié Bokhari’s work appears to be traversed by a similar irreducible melancholy, but to be intended more as the romantic spleen: a fertile melancholia, which allows this place of contemplation for the artistic genius to reflect about their own position and condition in the universe.

There’s nostalgia, longing, but also a possibility of redemption and regeneration animating most of Saniè’s works, as they unveil the concerns of a young woman confronting secular traditions, the pressure of societal and familial expectations, and the irreducible need for a spiritual elevation in a detached urban contemporary life.

Interestingly, Sanié often represents double or multiple figures that in the painting as they coexist with the central one as shadowy and eerie presences: they’re both the projections of the self and a reflection of the multiplicity of characters, identities and pulsions coexisting within the individual.

After going deeper in discussing her technique and use of materials, I can observe how this duality also exists in the process behind her canvases.

Walking me through it, Sanié reveals how everything often starts as pure abstraction: she loves to release herself with free movements of color pigments and painting tides that land on the surfaces.

Following this first phase, there is then the building stage, shaping and molding textures over the surface with the unique use of the pastel ground she has developed over the past months.

The additional layers of graphite and paintings will be finally be absorbed in some unexpected and interesting ways by this prepared surface, enriching the elaborated atmospheres of the canvases with multiple effects obtained within in this tense oscillation between intuition, intention, and improvisation that traverse the entire process.

On the other hand, when it comes to outline her figures, Sanié largely relies on her previous study of traditional miniature techniques, which she has then adopted and developed in a very contemporary and personal way.

Most of her characters and compositions are still inspired by South Asian ancient miniatures, creating these mysterious spaces that escape the Western canon of perspective to explore a different spatial conception that contemplates and combines both the physical and the inner world. From those, she maintains the ability to build a field of vision with equal legibility, combined with an overload of the senses between lines, colors and her atmospheres.

Sometimes haunted and uncanny, often unsettling, her visionary works seem to tap in this way into deeper human truths that reconnect to ancient wisdom and spirituality.

Her composition results as suspended in a “placeless place”, an a-topia, a no-place between utopia and dystopia which, extracted from the linear time, already encapsulates the universality of multiple consciousnesses, narrations, time and space, in a pluralism of references.

In some of the recent works by her we eventually observe a visual manifestation of this “double consciousness”, typical of the diaspora experience: a metaphorization of a deterritorialized critical consciousness, that already approaches a sort of ontopology dealing with the nature of being, but already transcending cultural specificities.

Interestingly, even the Indian miniature had an attribute of pluralism incorporated in its development, which proves the richness of Indian culture: despite Indian miniature painting having existed in various forms since the 9th century, there was no cohesive vision until the Mughal Empire was established in 1526 when the genre was also officially established, but started to reflect also the multiculturalism encouraged by the empire: Mughal miniatures are already a blend of the vivid colors favored by Indian painters, combined with the fine lines preferred by Persian painters and a European influence from artists like Albrecht Dürer, brought to India by Jesuit missionaries.

With the occasion of her recent solo exhibition at KAPOW, Sanié also found herself back to sculpture, making a captivating disco ball that immediately held viewers attention in the space, incorporating writing in Urdu characters on its shining surface.

As the artist explains, the piece was actually inspired by a recent event: during one of her recent trips back to Pakistan she went to a houseparty organized by a friend and he had hung from the ceiling a disco ball with a verse of the Quaran on it.

As the photo of the discoball and the party started to circulate on the social media a few days after, her friend received some harsh criticism accusing him of blasphemy – an episode that reveals the strong presence of religion, how it is approached acritically, and the ongoing policing of both public and personal life.

However, in reiterating this with her work, Sanié wanted to play with some of the existing stereotypes on this side of the world, unveiling how in the States, Arabic characters are immediately connected with religious extremism or narrative, while in her version of the discoball the writing actually reads, “Welcome”.

She’s now working on more of those, and willing to explore the extent of this specific provocation and sculptural integration of her presentations.

As Sanié reflects, the differences between the two countries are enormous, especially for a woman artist able to personally experience both the contrasts but also parallels between East and the West, instead of always opposing them.

In fact, as we would later conclude, the level of freedom between the two countries is just supposedly dramatically different – if we look at the current extreme polarization of opinion and tension in the States, we would eventually realize the congruence of conservatism, and censorship.

Another proof was offered by the reception of one of her central pieces of her last solo exhibition: in a symbolically powerful canvas the artist had portrayed herself smoking, with the legs up and a series of embryos as ghostly presences fluidly coming out from her, lying over a field of red mushrooms.

The piece appears situated in an alternative dimension, before and beyond consciousness, in the possible projection of the self that can be formulated lucidly in an altered status.

Despite the piece being arguably one of the masterpieces so far by the artist,collectors would often shy away, as it was too loaded for many of the interested parties

All of Sanié’s artworks appear to test and question the actual freedom allowed, in different contexts, for some dense personal narratives offered by a Pakistani-born young woman in present-day highly polarized American society where politically correct works are still preferred to more challenging ones.

In this sense, the work of Sanié turns into a critical platform of cultural dialogue and confrontation, investigating limits and possibilities of cultural and personal exposure and expression in different contexts, while challenging the contemporary stereotypical engagement with the “Muslim world”, and more specifically the Muslim woman’s body in the United States after 9/11.