Where things happen #31 — February 2025

In her artistic process, Shuyi Cao appears to fully embrace the principle of entropy that rules in the cosmos: materials, organic and artificial elements come together with their different stories and origins to blend and collide in fluidly eclectic ensembles. The artist embraces hybridity as the only possible philosophical, biological and existential condition to worldmaking where matter and energies are in a continuous flux of transformation.

This could be why her intuitive sculptural composition develops and evolves following a spontaneous process that surrenders and embraces nature’s apparent randomness and eventually responds to a universal cosmic order undecipherable to humans.

We met the artist on a late January afternoon in New York, where wintery gusts had taken over for weeks. Cao’s studio is in a complex in Bushwick we had already visited for previous conversations. It is a multi-functional building right at the border between Bushwick and Bed-Stuy, which must remind her of an industrial building in China, where the artist grew up.

Once the conversation reaches the ease of a more spontaneous and familiar exchange, we would learn that Cao originally moved to the U.S. after a sudden revelation she had during her study period in Milan that inspired her to make a radical life change, turning to art from her initial path in social sciences. “Art in Europe is everywhere, unlike what I have experienced growing up.” she recounts, “I realized art can be a way of living a life and I decided to pursue my artistic inclinations.” While Cao had been drawing since childhood, she had never really ventured into art-making before that moment, as it was never presented to her as a possibility throughout her upbringing. As we speak, however, it feels like she has just a call to pursue something already destined for her.

When she made that decision, Cao became an artist primarily as self-taught. “Today you can learn most things on Youtube,” she comments, and that’s where she started, later enrolling at Parsons with her first oil paintings. Even this program, as she would later admit, didn’t give her much in terms of technique, as they were mainly concentrated on theory and criticism. However, the city exposed her to a full spectrum of creative practices. As Cao notes, most of her learning in art-making came from a restless and very intuitive exploration of processes and materials she embarked on, especially apprenticeships working in various studios from fine arts to set design. She attributes her wide range of material choices and techniques to these experiences, and it seems that she has found her unique approach to melting diverse influences into her own artistic voice.

When we visit the artist in her studio, the works range from her signature ceramic sculptures that integrate organic relics, to new aerial recycled sea glass multimedia compositions and small hand-blown glass pieces in the back. She considers her materials to be in a constant flow of circulation – from the outside world to the inner ecosystems of her own studio. Here, discarded plastic bottles are refabricated into delicate ethereal floral shapes. Waste glass bits found along the shoreline are fused and morphed into translucent modules. Even her ceramic sculptural compositions are often parts of previous forms she fired elsewhere and reconfigured in the process. “It’s expensive to rent a kiln, so even if something is broken, I never throw it away. I just leave it there. Then, months later, they convert into new pieces with other debris I found.”

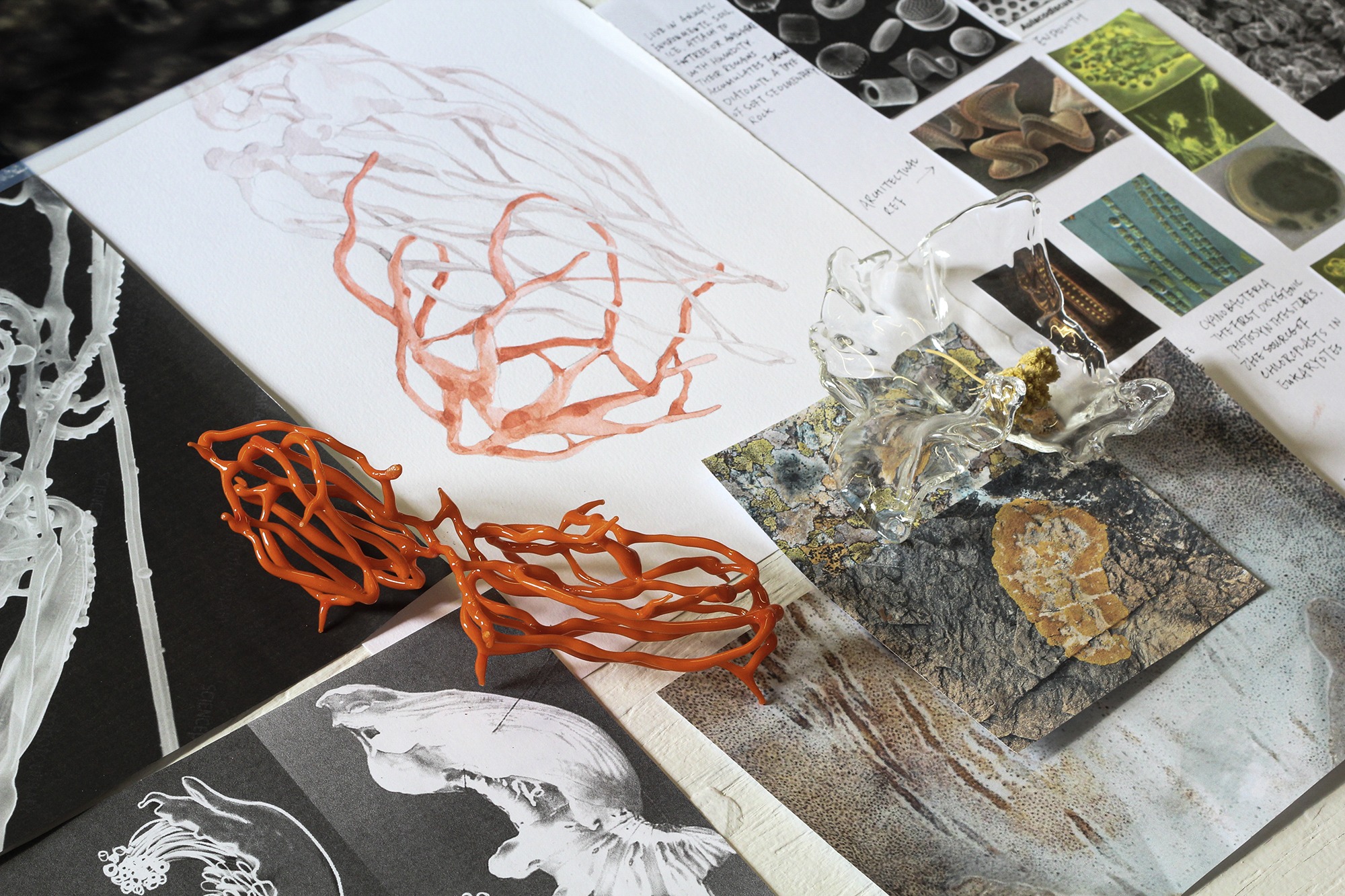

Between the formed and forming sculptural entities, the artist has an entire archive of both organic and artificial fragments that looks like a taxonomic atlas of the relationship between humans and the natural world. At the same time, this archive provides the artist with a personal vocabulary of potentially endless formal and symbolic configurations. Everything here feels still in process and subject to new potential transformations and adaptations.

“There are so many poetics and philosophies in nature that speak to how I make work.” As Cao describes it, her art-making is more about co-creation with nature and its materials. “It’s like I’m collaborating or playing with them, and we generate something together.” As Cao suggests, in her artistic process, she feels more like a vessel, channeling energies and forces to new combinations of sense as she observes, studies and very intuitively interprets materials’ infinite expressive and esoteric possibilities.

Notably, by testing idiosyncratic compositions, Cao most often reaches a level of structural complexity, layering and blending that eventually seems to imitate or evoke organic processes already happening in nature. “Sometimes I think I’m just echoing the different adaptation strategies that living beings evolve within their environment,” explains Cao, elaborating on how, through this process, she’s evoked those alternative models of hybrid coexistence, and the embedded structures universally shared across different entities in the cosmos from the micro and macro levels.

The artist has been adventuring not only into the physical recombination of matters but also into alchemical processes that deal with a more molecular universal structure of reality between elements, processes and forces.

“Most of my work involves a kind of transformation, translating between different scales, lifeforms, and dissolving the boundaries of the living and nonliving, organic and inorganic,” she says, as she shows us the other side of her studio where she’s experimenting with some chemical, simulating early Earth’s metabolism, which she later photographed, unveiling the aesthetical potential of this inherently abstract composition. These images are then incorporated into wall-mounted resin pieces resembling miniature landscapes or alien meteorites. Derived from her first stoneware series from four years ago, the artist described these sculptures as “fossilized fictions encrypted within terrestrial matter.” These sculptures are created by molding forms and textures from actual geological surfaces on sites, then embedded with indistinguishable natural and urban debris.

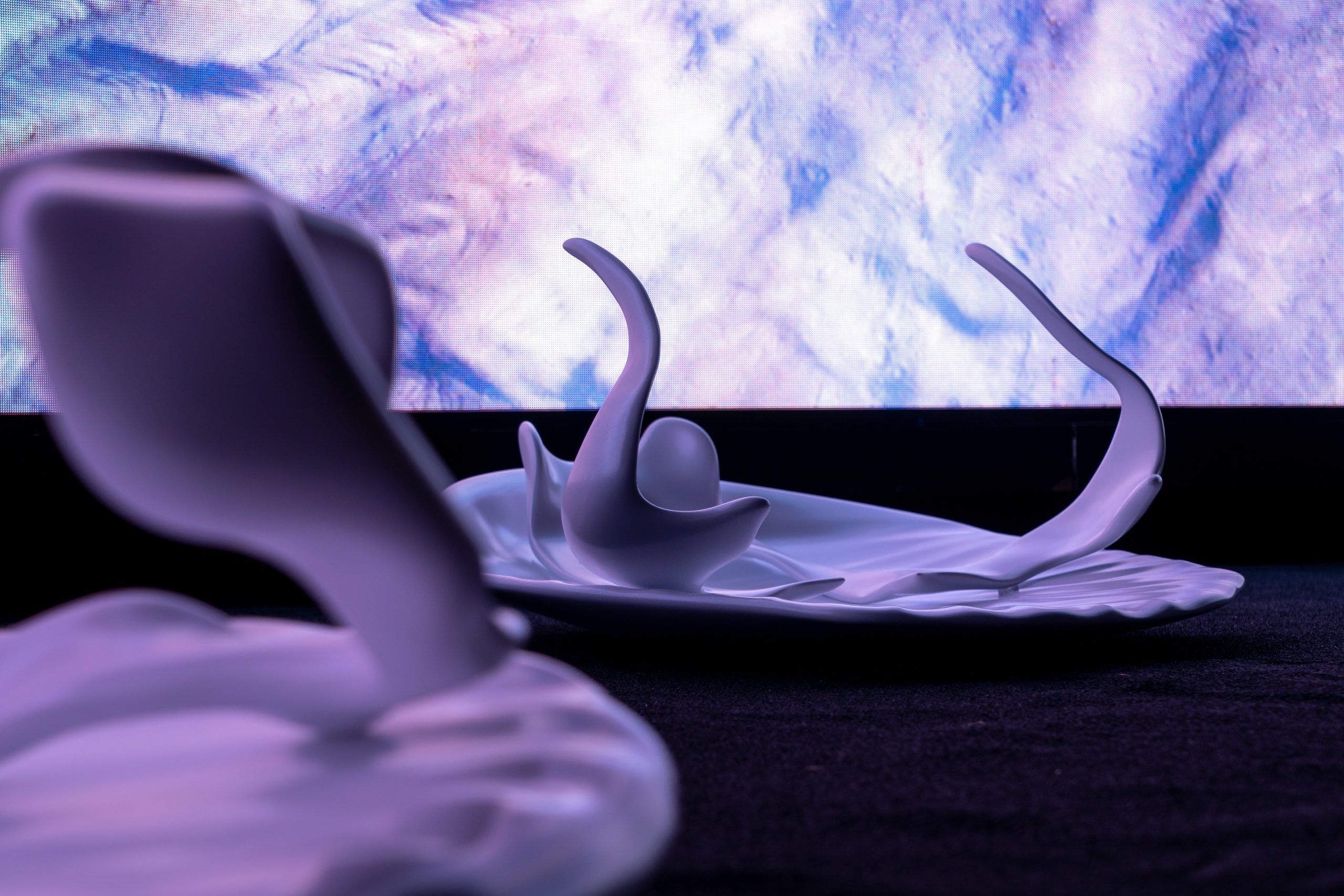

Such transmutation of matters also extends to the digital realm. In her video work, microscopic imaging merges with AI-generated and hand-modelled landscapes in a virtual game engine as archetypes of future remains of a globally interconnected techno-sphere. The meditative scenes render the deep-time metamorphosis of the inorganic element from primordial broth to coexistence across species and intelligence. For the artist, her making philosophy engaging material transformation is reflected in the fluid transition across the physical and digital worlds: “I am collaborating with natural intelligence and machine intelligence and there is no hierarchy between them. The very unit that builds our technology comes from stone and ultimately from the stardust which we are all a part of.”

While her way of describing her almost divinatory approach to forming her art-making sometimes seems to imply a more spiritual dimension, Cao cautiously points out how she grew up in a very secular China, which was going through a significantly accelerated modernization and industrialization, repressing most of its millenarian ancestral spiritual wisdom and knowledge. Still, this context and tension might have eventually inspired the artist to ponder more profoundly on production and labor and how anthropological interventions and dynamics have long run against a secular order of all things.

A similar tension emerged as she remarked on how the Western culture tends to praise logic and the mind as superior to the corporeal, and within the course of Western art history, a dismissal of craftsmanship due to the distinction between fine and decorative art. Such prejudice never occurs in Eastern cultures, as she reflects, “In Asia, we appreciate craft as the craft itself embodies some kind of spirituality.”

There is still something deeply ritualistic in how Cao approaches her “craft,” especially when, as an alchemist, she plays with different relics and possible physical-chemical transformations, melting them into a fluid dimension to form new aesthetic and symbolic compositions of sense.

Some of her most recent works add another multisensory aspect, exploring how materials can function as remnants of entire environments. Shells and rocks she collected during a recent film project in Uzbekistan resemble dream catchers or antique instruments, where the sound of a desert – once the disappeared Aral Sea – can manifest again through its natural archaeological relics. Again, in these works, Cao explores a level of co-creation with natural environments.

At this point, it is pretty revealing that Cao describes her artworks as a sort of ecosystem. Within and through them, she’s already testing how human production can realign with the cosmic order of natural circles of creation, transformation and destruction as she tries to envision a possible more harmonious adaptation between nature and the human era.