Sim Chi Yin in conversation with Elisa Carollo

As a former journalist before becoming a photographer and artist, you started your career in visual arts first reporting in a fairly factual way and adopting a primarily documentary approach in the attempt to respond to critical geopolitics and denounce injustices around the world.

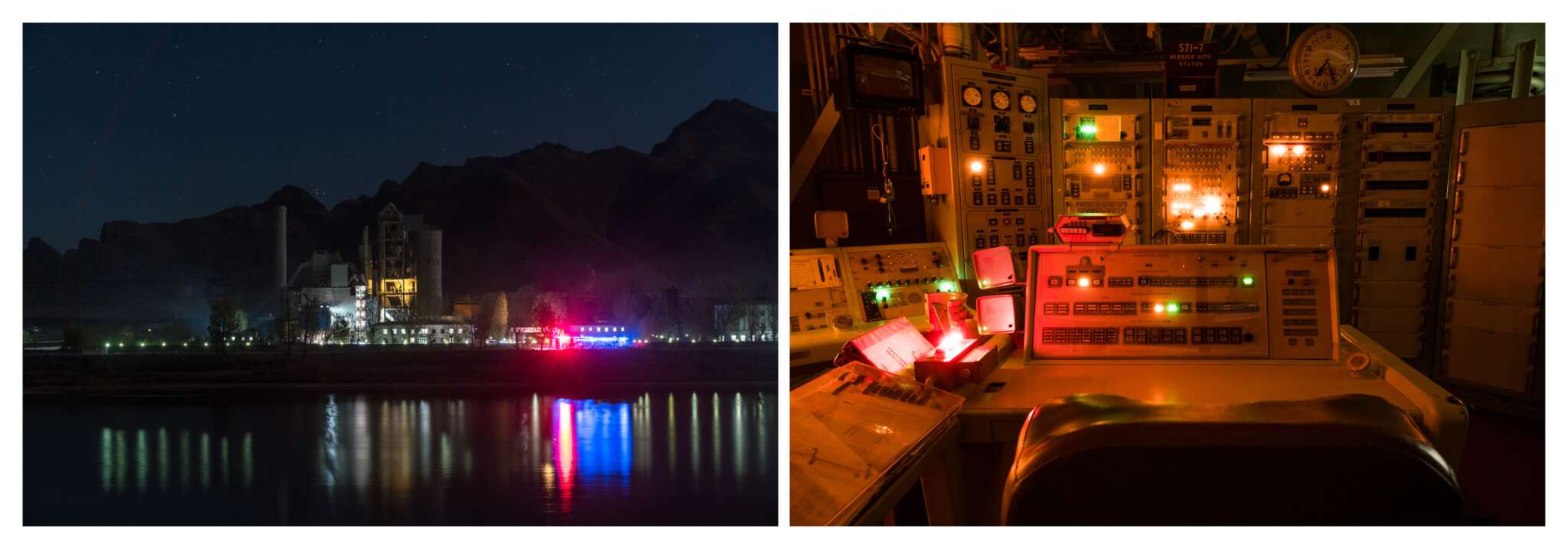

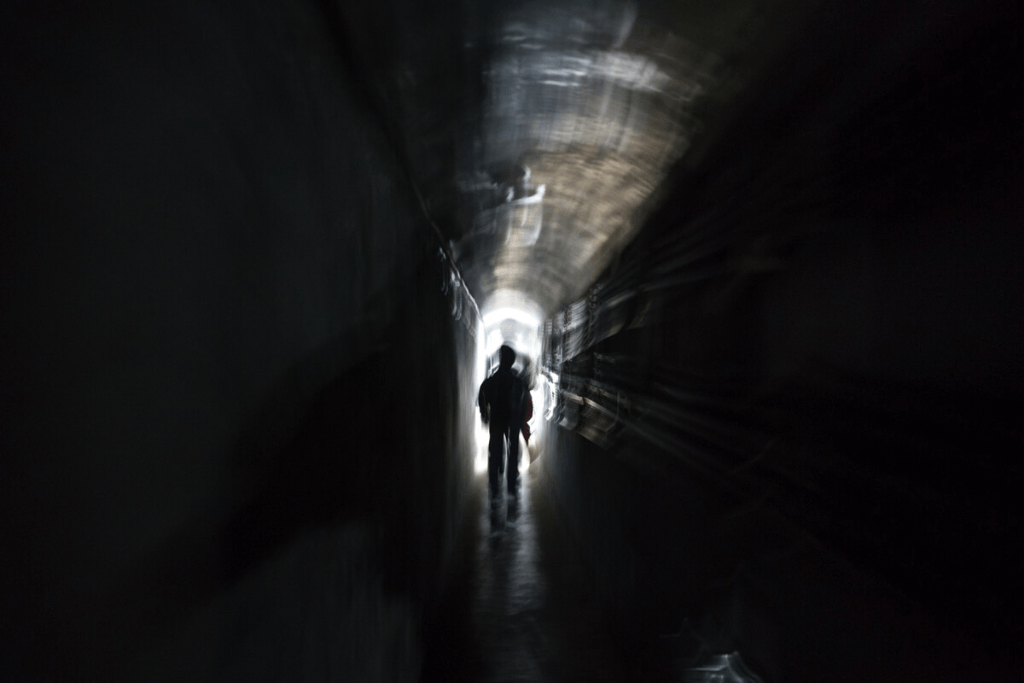

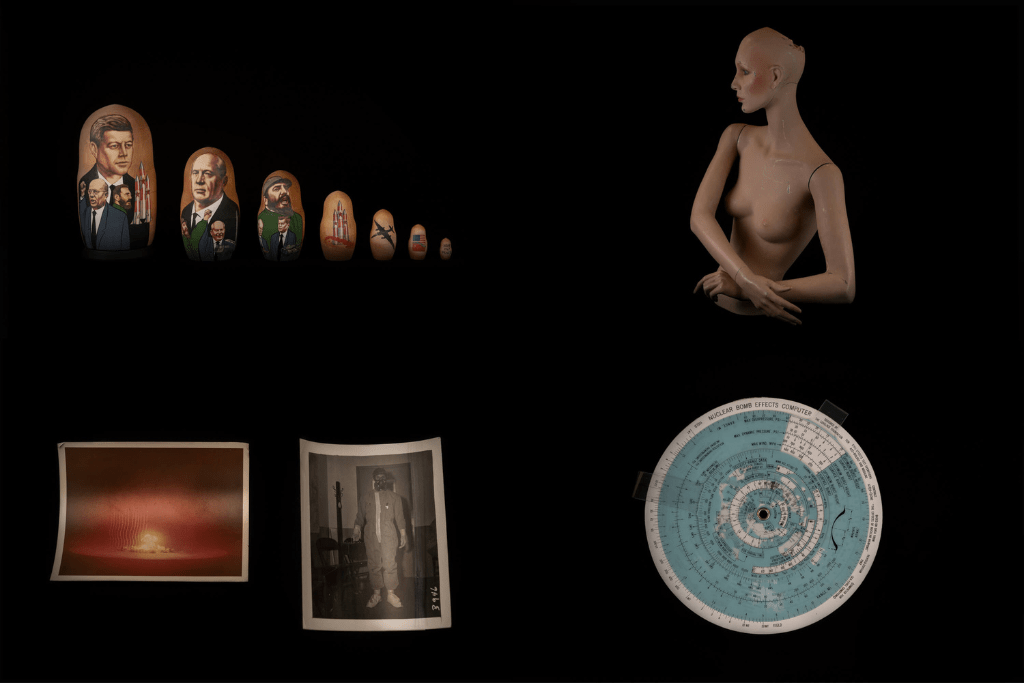

The series we are showing as part of the exhibition at Fondazione Imago Mundi, Most People Were Silent, was commissioned in 2017 for the Nobel Peace Prize, and takes us to the two sides of the nuclear equation, juxtaposing highly emblematic pictures from the China-North Korea border to U.S. missile and military sites.

Despite the shoots’ apparent objectiveness (having as the only aesthetic choice the time of the day when they were taken), these pictures appear to have already some purposely searched abstract quality that suspends them in time and space, infusing them with an enigmatically revelatory character. The nuclear war, itself, is something that still for most of us very abstract both in the news and in theory.

However, iIdentifying specific visual clues in the landscapes, you were able to show what the actual nuclear infrastructure looks like, even without directly showing the sites: the weight of these landscapes, the erosion of the earth under heavy but apparently quiet industrial complexes and machines allow the observer to feel the concreteness and the heaviness of the nuclear threat, and its consequences.

Can you explain more about this approach, and how you proceeded in selecting the subjects to build allegorically and enigmatically a specific message, even without being able to show the factual nuclear weapons or sites?

People like to focus on the fact that I’m a former journalist, but even before that, I was a student of history. I really do come from a kind of training that looks at evidence and facts. I studied Cold War history at the London School of Economics, specialising in Maoist China. Then I went into a career that was again, in effect seeking truth, working in text journalism and then reportage photography. This was before doing things with a more artistic methodology, to open things up into a more speculative register. I would say that this body of work around nuclear weapons was key in that transition to the more speculative and the more open-ended. In very broad terms, the approach I chose to take with the nuclear series was very deliberate. It was intentionally not trying to be didactic: I wanted to try to use ambiguity and looking at a sense of place and site to suggest other meanings. I think the nuclear topic itself is a very polarizing one, and I feel we live in a very polarized world with a very different information system and environment than when I was younger; the efficacy of journalism and didactic messaging, whether through civil society, journalism, politics, or even the arts, I feel has actually been reduced. Therefore, I’m now more interested in finding ways to open up conversations even with people that disagree with me, even if I have a point of view about something.

Through a strategy of juxtapositions these pictures open up to a broader spectrum of meanings and allusions, beyond their factual visual referents.

This method appears to perfectly comply with the “theory of montage” as epistemological principle capable of relating heterogeneous orders of reality. Something that can be referred to authors such as Aby Warburg, Walter Benjamin, George Bataille and Georges Didi-Huberman in particular, drawing from the Hegelian idea of Dialectics: dialectic juxtaposition of images even anachronistic or with opposite meanings, unsettle any simple reading, producing an opening of our gaze.

In this sense, sensitive montages often serve to pose new questions of intelligibility.

This is most often the case when they succeed in composing a particular anthropological rhythm, of the world of images and visual documents.

As you commented, being more conceptual this series already anticipated a shift in your practice, which progressively transitioned to explore more imaginative realms.

In opening up the images, you’re already addressing also the inherent fallibility of photography to be a purely objective witness, as they inevitably always imply a decision behind, of what gets included or excluded.

Can you expand how these reflections took you to shift from documentary photography to more artistic realms, and how this transition somehow reflects a perceived inadequacy of reportage photography to critically document what’s going on in the world? What’s your perception of the role of reportage photography, and journalism in general, in documenting today’s world events?

I was trying to find both a visual language and method that could really open a conversation. Interestingly, the museum that had commissioned this work had instead a very specific point of view, and they had actually commissioned me to make a work that advocated against nuclear weapons.

So, we actually had some discussions about the conceptual and more abstract approach I eventually applied in this body of work, as it didn’t want to shout the message from the top of the mountain.

The way they framed the exhibition in the end was quite didactic. But you know, they are an advocacy organization. They titled the whole exhibition “Ban the Bomb”, which made very clear their stance. They had a clear message: they wanted to advocate against nuclear weapons.

I was trying to make a body of work that would invite someone who was pro nuclear weapons into a space to maybe contemplate their position, to at least begin an open-ended conversation that the abstracted images have the potential to spark. The body of work basically pairs historical nuclear sites in the US with places in North Korea on the North Korea Chinese border which were as close as I could get to the actual military and nuclear sites in North Korea known to scholars but inaccessible. The overall approach was to find visual parallels between the two countries which are the ends of the nuclear equation in the world and, and in nuclear history.

I found some uncanny visual parallels: for example, nuclear sites in the US have these super long, tall chimneys and I found very similar looking things in North Korea, almost kind of unwittingly. But the idea was to not give any explicit information on the precise context where the images were taken, so that on first viewing, people might be at least momentarily confused about which photograph shows North Korea which photograph was of the United States.

This was the thought process I was hoping the diptychs would spark, making people wonder whether they can be so sure about, which country was allowed to be the world’s policeman and which country was just basically a “rogue state”? How are we so sure of our moral judgments, if we can’t even visually tell which was which.

We are aware of how history has been narrated from the winning side, and controlled with a specific and strategic narrative – from the first war reporting by Herodotus, to the Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan war.

This inevitably implies an omission or erasure of other perspectives, that are not therefore recorded and often lost.

But, as you said in a previous interview, Art provides space to look into these silences and these gaps: In the past years your research has focused, in fact, in questioning the reliability and primacy of different archival sources, working, again, dialectically, on different photographic and video documents omitted from official narratives and exploring counter history.

With your artistic practice and by applying this dialectic approach described above, you’ve been able to open up these images combining and juxtaposing official and personal narratives (including family archives), as well as different historical and geographic contexts to reveal similarities and contradictions, and open new possible reading of our past, for our present and future. This seems to perfectly respond also to Walter Benjamin’s idea of “politicization of art’ through a conscious process of interruption operated by the artist, assembly and change of function of the images supposed to document our society.

Can you share your thoughts about the possible relation between art, public memory and alternative histories? How do you believe art can help shape an alternative public memory?

I came from history training into journalism and foreign correspondentship, then moved into documentary photography and eventually ended up feeling that being a research-based artist is the most suitable for what I want to do right now. And I suppose this journey encapsulates what you’re trying to ask in this question. To take this path, I definitely had come to believe that art has a very important role in creating alternative ways of understanding history. And contemporary issues, in particular.

There are many research-based artists who feel strongly this is the arena in which you can bring certain things to light and shift the spotlight from, in contrast with mainstream communication. In my case, I worked on specifically on one project around the nuclear threat, but more broadly, I’m looking at memories from the Cold War. I’m also looking at historiography and how we can challenge official historiography about certain issues. For instance, a long project I’m doing on the anti-colonial war was in British Malaya – known as the “Malayan Emergency”. And to some extent, you could say that even the project I’m doing on how the world is running out of sand is a way to bring alternative perspectives: I’ve become convinced that is a way at least I can speak and introduce different perspectives and forms of narration into the picture.

Many scholars have written about the relationship between art and memory, like Michael Rothberg, Andreas Hussen, Marianne Hirsch. I’m not a memory scholar, although I’m doing a PhD and I am writing about how my own artistic intervention can hopefully have some kind of bearing on the public memory of the specific context that I’m working on. So I do believe that it can play a role, but I think it’s also worth noting and being realistic about what impact that really has on the world and that, you know, really does reach a small number of people in the audience. I became convinced that in art there is room for nuance and complexity, and slowness, in taking these issues. Most of the places that I lived in before — Singapore, Malaysia, China — these are the places where most of my work kind of originates, and where the political space and the civil society space is suffocated. I’ve come to see the art space as often the only space left where complex, alternative or counter-narratives can be discussed. I’ve also realized between fairs and exhibitions, art’s reach is to a very targeted audience. But at the moment, I prefer this hopefully deeper engagement with a small group of people in a gallery/exhibition setting over the huge reach of, for instance, publication on the front page of the New York Times. But I also make books, given talks and am also experimenting with performance – so I’m working on multiple ways to show the research, to speak about these contested memories.

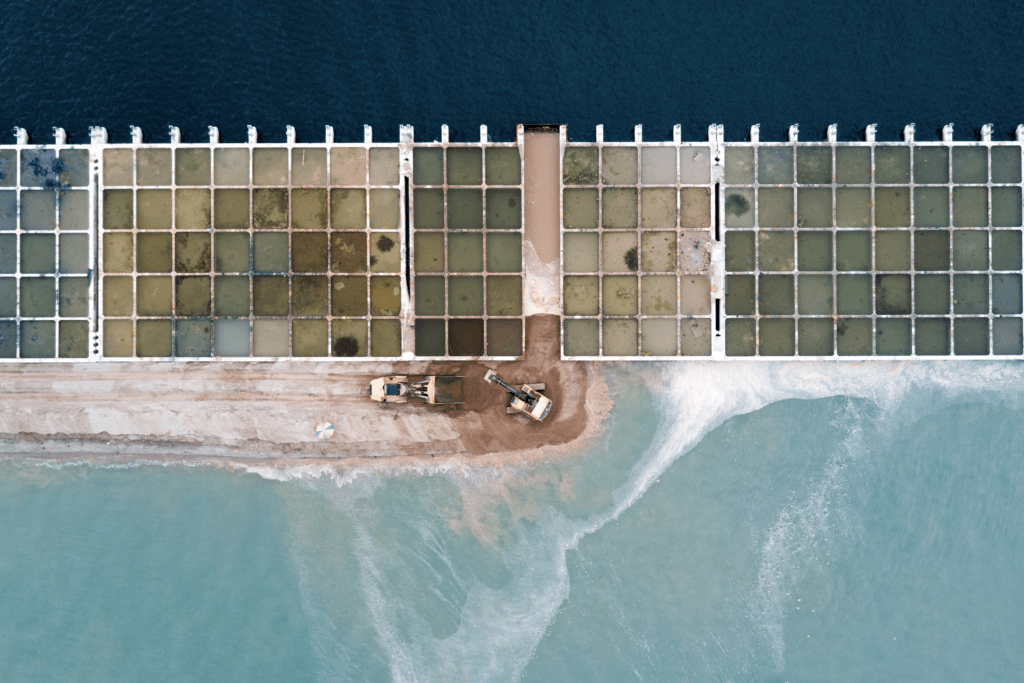

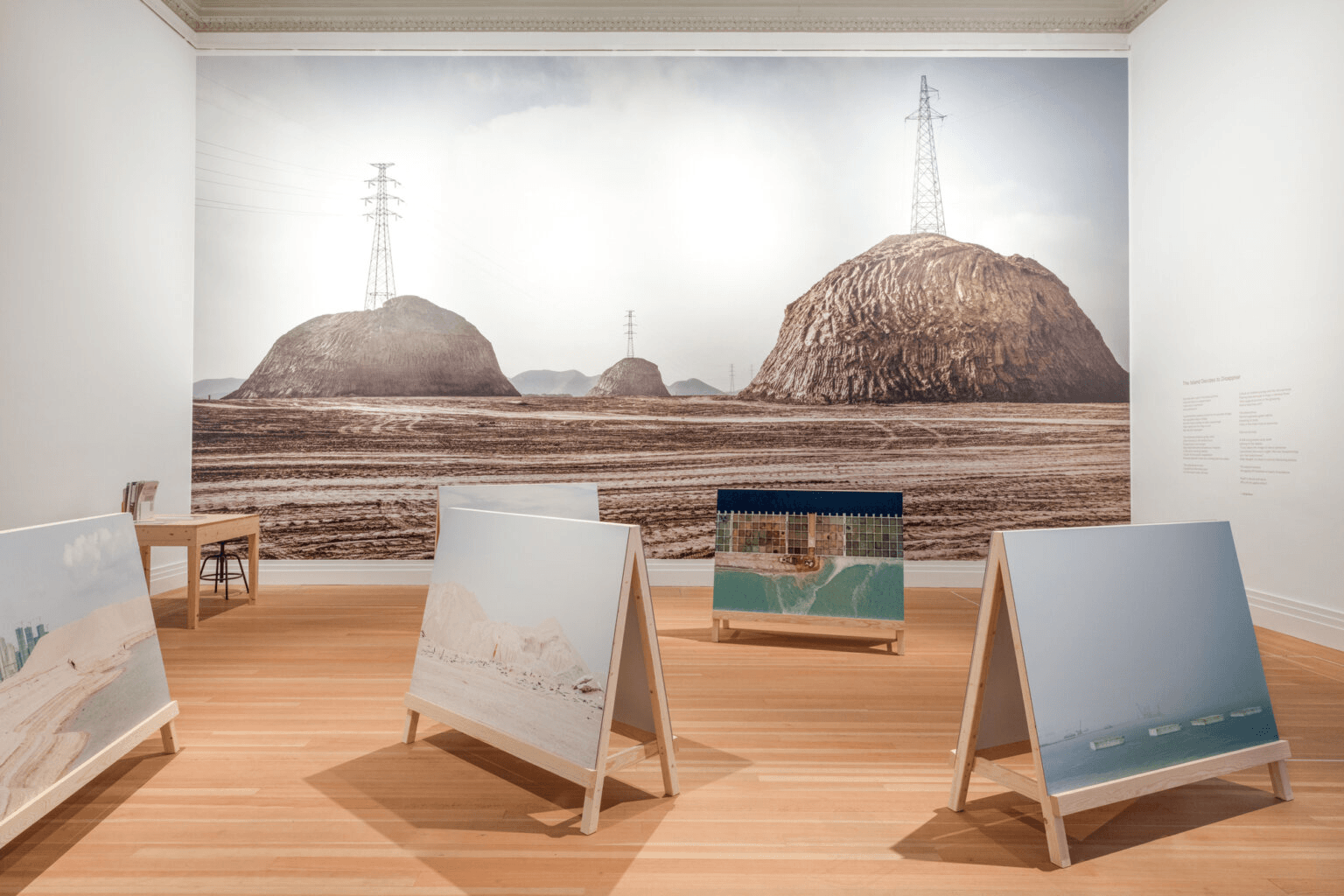

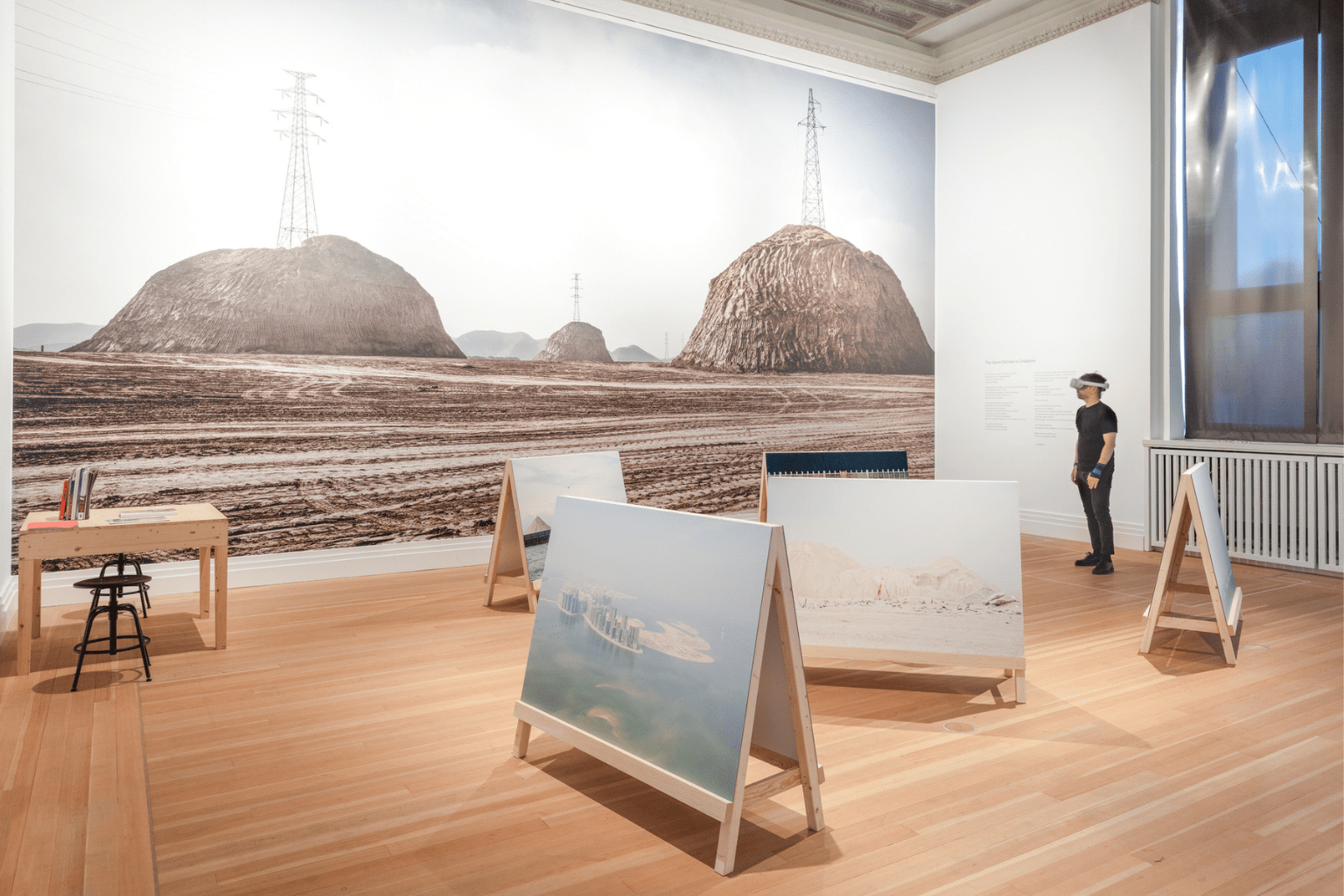

Both the series we are showing and other works that followed, prove how you often approach landscapes as a repository and archive of clues and information, that can allow us to open a dialogue about critical geopolitics of the past, present and future through images. Buildings, public infrastructures and other anthropological interventions, as well as the results or damages caused by them on the territories, can be revealed as potential causes and threats of future diplomatic tensions that may lead to new economical and political conflicts, despite these are still largely “unsaid”, “undocumented” and “unreported” officially. I know that recently you’ve been developing a visual quest in this sense, focusing on the global depletion of construction sand, with some works now going on view in Berlin at Gropius Bau, and later at Barbican Center in London, UK.

Can you tell us more about this project and the specific approach used in documenting these natural/industrial phenomena to address their broader economical and socio political implications?

I think it depends on the body of work.

In the body of work around the history of the anti colonial war in Malaya, I basically worked from informal sites of memory through either secondary literature or through actual in situ interviews. I looked at sites that had some kind of folk memory, for people in the area and then tried to photograph them in an evocative way.

Similarly, in the Shifting Sands project I’ve chosen those sites for kind of obvious reasons: they were either places of extraction of sand or they were sites of storage and use of this now very prized commodity. I also look at huge areas of land reclamation, that’s how the sites were chosen.

Of course, I’m interested in thinking more deeply about what is this land that we stand on? What is this territory and terrain that we move around? As I’m coming from Singapore – which is the world’s biggest importer of sand per capita- I’m very struck by the fact that there’s no discussion in the country about where we actually acquire the sand that we used to augment our own territory. This is mostly from our neighborhood, from the poorer countries in Southeast Asia which are running out of sand as well and then we buy from further and further afield.

It’s troubling to think what this means in essence: wealthier countries buying up pieces of poorer countries and moving it to where they want.

Sand is taken from the river or the sea: it comes with its own history of people, its own memory, human and non, containing a more metaphorical kind of sedimentation.

I think where the sedimentation comes from, and, and what we’re doing when we move these things around.

The Gropius Bau installation, which has been open for a couple of months now, it’s beautiful: people go there and they take pictures with the physical installation. But what I’ve done in this case to kind of complicate my own practice, and my own medium of photography is to create a narrative piece in VR, and it’s been really interesting to see how this tool became an important part of the narration.

I mean, landscape photography often uses the tools of seduction to hook people in. There’s a table of research materials about the depletion of sand in the world. But if you sat down for 10 and a half minutes to experience the narrative VR piece I’ve newly made, you get something very different from the installation. The VR was a very costly experiment and I remain a skeptic of the form, but I’ve become quite convinced that this piece was worth doing.

I’m definitely experimenting with different forms, and media, but I think the story-telling core remains the same. At this point, I’m going where the materials leads me, in terms of helping them find form in the world.