Where Things Happen #9 — Nov 2022

Amy Bravo was born in New Jersey (NJ) from a Cuba/Italian family, all her work can be described as a mission to create her own identity in a complex world, battling against and within psychological precepts to reconcile a stratified lineage, connecting her back both to Cuba and the South of Italy.

Amy graduated with a BA in illustration at Pratt, and only later moving to painting which she then developed along with sculpture during her MFA at Hunter College, New York.

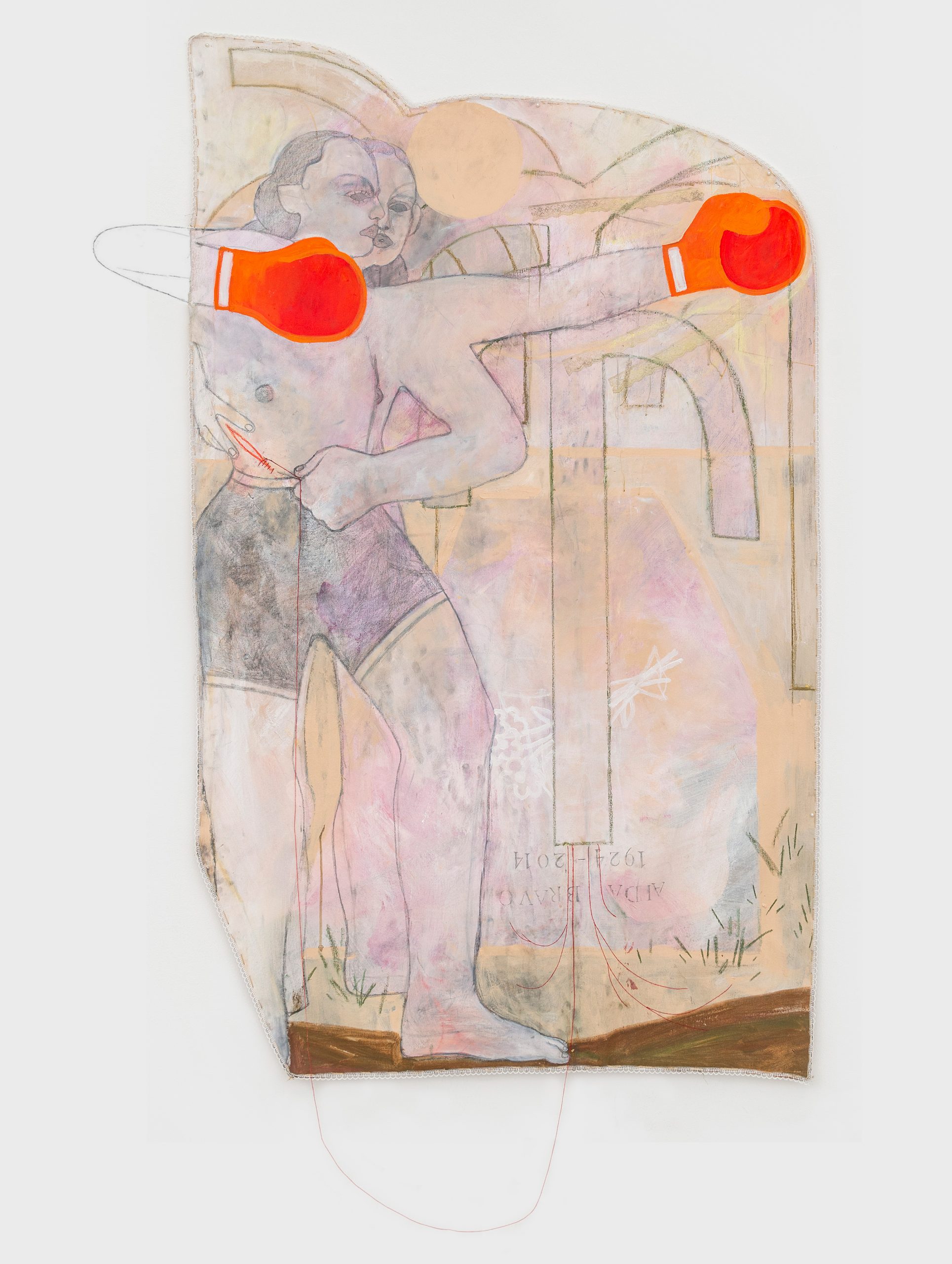

Still, her approach to the medium is anything but conventional: rejecting completely traditionally stretched canvas, Amy prefers irregularly shaped supports, often combining multiple layers and techniques such as found objects from personal archives, pieces of fabric, leather, and even dried leaves from plants pertinent to her mythological world.

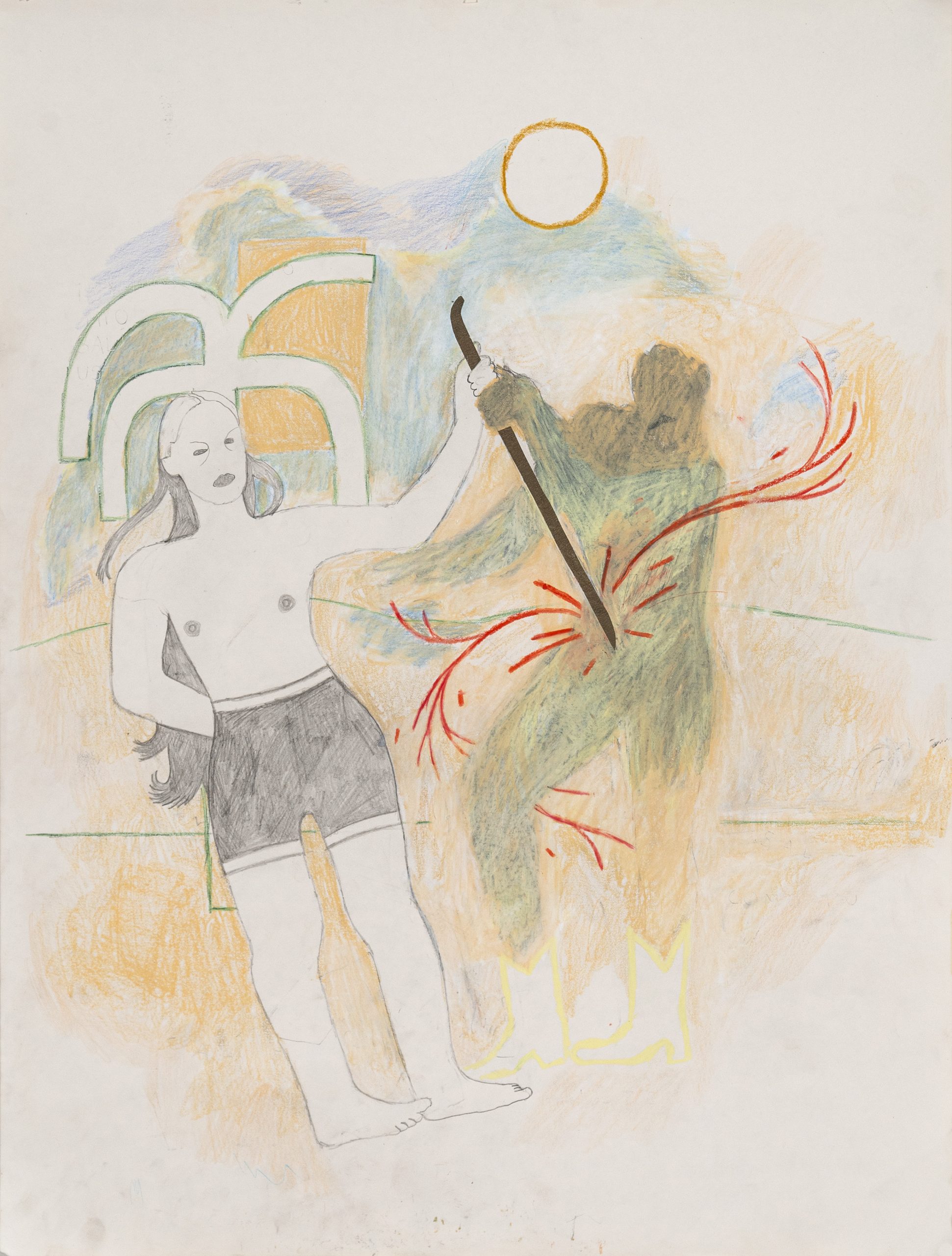

Her work often starts from a graphic sketch of its main narrative structure, she then proceeds by intuitively adding, repurposing and assembling elements to build a scene that expands beyond the container; her figures tend to take over the wall with their movements accompanied by a set of ephemeral architectural elements, all expressing a need for a “resurrection” in a story that doesn’t yet exist, but is rather a figment of the imagination mixed within Bravo’s own realities.

Growing up with herfather’s rejecting the family’s past in Cuba due to American interventions and misinformation campaigns, Bravo’ work centers around a passionate and honest effort to re-appropriate and rebuild a connection with this heritage by combining fragments of family stories she has been listening and fantasizing about, since she was a child.

However, she never had the chance to visit neither Cuba nor Italy yet, this memorial reconstruction is purely mental, often imaginative, and largely informed by a nostalgic relation with her grandparents and their loss, as well as all the objects surrounding her growing up.

Amy confesses that for this specific reason the representation often turns into just caricatures, relating with what the critic Charles Merewether said, observing a general tendency of Latino artists to loosen images from their signifying function.

This aspect is made quite clear by the way she represents palms: standing as stereotypical and simplified cartoon-like form, they prove this suffered lack of precise knowledge and experience of their literal form, never having experienced them in person, aside from spotting some during her recent Miami residency at Fountainhead

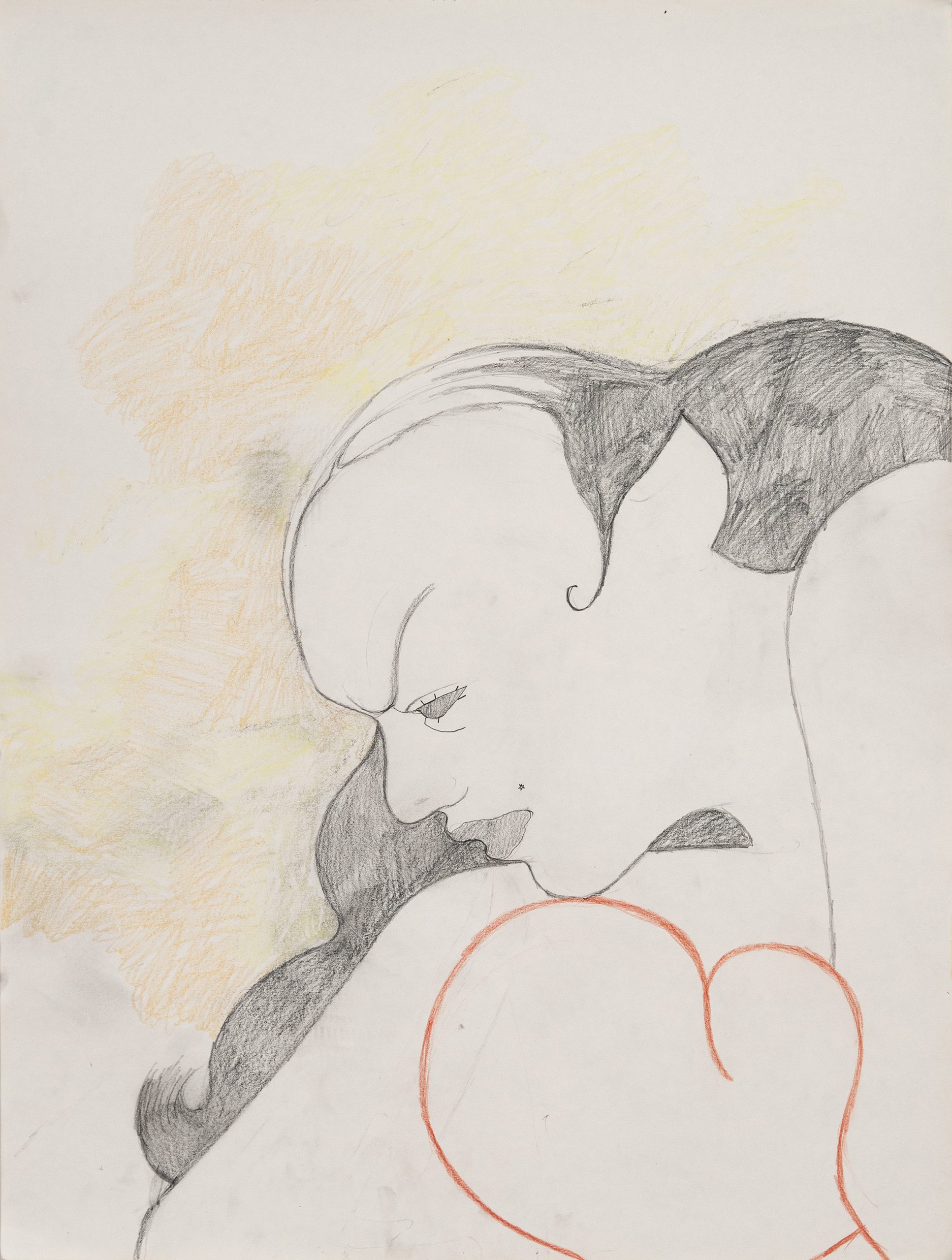

Analyzing her style more in depth, all her characters are purposely represented in evanescent,pastel sandy, pinkish and beige tones as they only exist in a murky, allegorical dimension between memory, subconscious and personal utopia.

As Amy describes them, they look like pale ghosts emerging from a dense morning fog, which she relates a vision of Cuba, due to its geological location and how she it, from some verses of the poet Arenas.

Built of few raw graphic lines, their silhouettes fluidly blend with the surrounding atmosphere, trying to resist the erasure of the oblivion.

Everything appears as suspended in time and space of displacement, creating scenes of dense symbolism, where this imagined story can still “manifest” in its ownspace, rehearsing lost memories or fantasizing on an idyllic alternative future.

On the other hand, fascinated by the idea of curio cabinets, most of Bravo’s multidimensional works reconnect us with the living rooms of many Italian or Latino grandmothers, where dissonant ensembles have been accumulated through life, or inherited through generations from the most disparate contexts: as personal archives they allow us to preserve memories, through these objects that outlive their owners.

Resulting from this practice of collecting symbolic and memorial “simulacra”, are then carefully positioned and repurposed with an underlying narrative. Bravo’s sculptures often appear as “altars of memories”, reminiscent of Cornell’s memory box, similarly adopting the surrealist dynamic of unexpectedly dialectic and juxtaposition that liberate and take on new meanings, beyond their singular physical elements.

However, when we deeply analyze her art making process one can observe how this, taken from a more psychological standing point, can be also related to the memory retrieval mechanisms: by recollecting moments, objects and fragments she progressively re-appropriates elements, to reconsolidate both an identity, and a family and cultural heritage at large, that she feels not only lost, but also denied.

As she explains, her artistic practice is driven by this desire to investigate the meaning of “being a bravo”, a mysterious lineage in which she now is in control of.

The works become an imagined platform where this legacy can be restated, and revived, and continued.

We can see in this both a grieving and cathartic process, that needs to go through denial and acceptance of the family legacy, to elaborate her own personal position in the world.

Not surprisingly, Bravo confesses that she spends a lot of time with her characters’ faces, striving to materialize and recognize in them somebody familiar.

For that reason they often end up in vaguely bearing resemblance to family members she has only met through pictures, recurrently in the end mirroring herself.

Engaging in this largely intuitive investigation of her personal and family subconscious, these figures materialize and conquer both the artist’ desires, and her fears surrounding queer identity, as well as the struggle in confronting this within her family..

These imagined characters then also try to personify the latin etymology for “bravo”, curiously enough meaning both hero, and later in Medieval times villain and assassin, as she explains serendipitously coinciding with her already present dual identity.

Although she represents all female figures, they are all but gentle or docile: as modern amazons, these imagined heroines fiercely stand in epic poses, often engaging in some violent actions.

Brandishing spiritually charged tools and arms, they confront their male counterparts which are represented only through symbolic and metaphorical animals such as rosters and bulls embodying some typical male attitudes, towards and over women.

All of Bravo’ heroines appear to finally gain control , empowered by this possible feminine alliance that alludes to overturning of the traditional patriarchal order existing in rural areas especially, but likewise enduring in modern urban society.

As Amy admits, her work tries to materialise an imagined countryside colony of fiercely queer women who don’t need male counterparts: defying any machismo and killing its metaphorical representations. They proudly claim presence in these scenes, with full control of their body, their future, and limitless queer expression.

Another recurring figure is the horse, represented as a guiding animal, in what she describes as the story of the “loyal horses”.

The horse, in Amy’s works both relate to her late Cuban Cowboy grandfather, who’s horse played a large role in her family’s subsistence, but also allegorically reconnect with both Celtic and Greek mythology presenting them as the animals accompanying the passage between life and death.

I first met Amy Bravo while she was still at Hunter: fascinated by the maturity revealed in her MFA graduate show presentation, I asked her a studio visit few weeks after which confirmed her strong personality, as someone able to stand on her own and vigilantly articulate her ideas and story despite having, as most of us, traumas and hurdles in a changing world which are still to be solved.

Since then, many other studio visits followed, and I was able to observe her making enormous steps forward both in her practice, and in the domain of the related narrative.

Our last visits were now in her new studio in Greenpoint which she shares with her “chosen family” of friends from the MFA program. As always her studio is a fascinating mess of accumulated materials, or a magnificent wunderkammer where personal and family stories can revive.

As she was preparing for two major presentations between a duo exhibition in the Swivel’ Brooklyn venue and a solo at NADA Miami, I could observe another interesting integration in her practice including more crochet, lace elements, and handmade embroideries: red thread runs through the canvas surface as a blood vessel offering an extra support that pull the pale figures out of this nostalgic fog. Flowing through the canvas, this vibrant energy is generated with a time-consuming hand-labor that allows Amy also to reconnect with both of her grandmothers, and all the women in the family.

Listening to Amy speaking about her works one can sense the undeniable talent animating her practice, but also acknowledge the very honest approach driving it, whose lexicon and reasons the artist is deeply aware of.

Since she graduated at Hunter last May, she has been showing constant evolution in her work, which is progressively finding larger appreciation, allowing us to imagine the many interesting directions she can take in developing both her visual language, her practice, and her overall career.