Features #13 — November 2022

Antonis Pittas in conversation with Nicolas Vamvouklis

Antonis, your work addresses cultural power structures in many ways: it communicates new perspectives on sociopolitical issues, questions the status quo, and suggests taking action. However, you once mentioned that you are more of a viewer than an activist. Can you elaborate more on this distinction?

It’s a question I often get, and my work has been categorized as an activist practice. In my work, I see myself as an active observer in the sense that I unfold (power) structures and social dynamics. I am not taking a stand in which I communicate what is right or wrong, but rather expose the ambiguity of these structures. The ambiguity of symbols frequently plays an important role. As an observer, I allow myself to deconstruct and reconstruct a narrative, avoiding didactics.

The visual language of modernism and its connection to politics is a recurring theme in your research. Who are the figures associated with this philosophical and arts movement that inspire you the most?

I am from Athens, where you are surrounded by the visual language of modernism or the beginning of it. The idea of utopian structures has always fascinated me; the simplicity of the lines, the proposition against augmentation, and the notion of simplifying. This applies, among others, to architecture, fine arts, design, poetry, and theatre. I am primarily interested in the Russian avant-garde, which arrived as a political movement. The thought that these people were trying to translate the utopian movement into forms and images intrigues me — and this vision relates to politics.

I remember the first time I saw your work at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam in 2015. The message “What does modernity mean to us today” was written on one of the clipboard pieces. How would you reply to this query/statement in 2022?

Back then, I would have been more sure and with a certain sense of hope. I don’t say that I am not optimistic now, but I am not so sure if modernity is the answer. Looking at 2022, I feel that things would have changed if modernity had remained in its principles. The question is if we are ready to accept those principles again and allow modernity to succeed.

In a project I did in Paris, Ι was talking metaphorically and humorously about the idea that modernity didn’t fail but was murdered. I created a crime scene in the house of Theo Van Doesburg, one of the most important architectural examples of De Stijl. With this work, I tried to point out that the failure of modernity has to do with the collapse of our existence; we didn’t really allow modernity to succeed. In that case, it has a future but must be based on very different realities. Let’s hope for those realities to come!

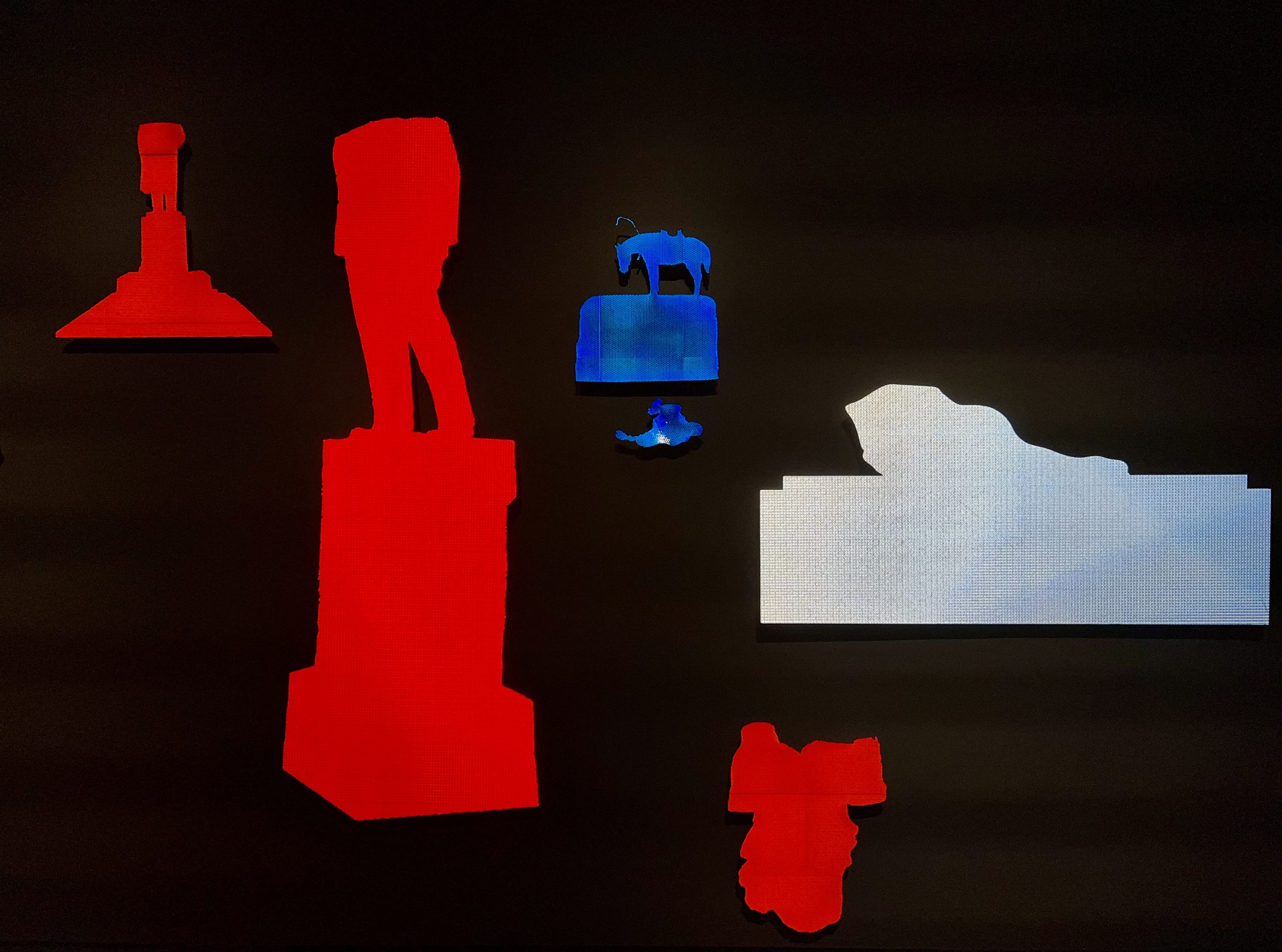

I enjoy how you play with visibility in the exhibition space by juxtaposing works and giving the audience the possibility to activate the interplay between multiple layers. Last June, you caught me flash-photographing “all done go home” in the exhibition “Statecraft (and beyond)” curated by Katerina Gregos at the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (EMST). It is one of the many works you recently created using reflective ‘prismatic’ foil. In which ways do you relate to this material?

Whenever I am in a car, I observe the outside world and the moments of transition from a to b, as I don’t have a driver’s license. I find the reflecting material fascinating; when you are on the highway, its role is to give direction, visibility, and protection, but mostly control. The reflective road signs represent a physical and visual form of state control.

We could also think about how the basic forms and colors of the road signs relate to modernist aesthetics, such as the significance of the circle, triangle, and the square for Bauhaus; they became the logo in promoting this pioneering movement. In addition, blue, yellow, white, and red were used extensively.

The materiality of this reflective prismatic foil brings a contemporary and temporal dimension into our discussion; this fluorescent element is there to attract your attention but also has a performative aspect when flashed. The material activates the viewer to participate and influences the visibility of surrounding objects.

At the moment, EMST also hosts your solo show “jaune, geel, gelb, yellow. Acts of modernism with Theo van Doesburg”. Your installation is part of a new program that invites contemporary artists to intervene in the museum’s collection. Considering your interest in transhistorical perspectives in art, I am curious about the challenges you faced while working in this direction.

In 2019 I was an honorary fellow at the University of Amsterdam. My research was based on recycling history: contemporizing history and historicizing the contemporary. With recycling history, I mean the cycles in which I believe that history in some way repeats itself.

I have long been researching the visual language and legacy of modernism and its promise for a better, more democratic world. The work “jaune, geel, gelb, yellow. Acts of modernism with Theo van Doesburg” came to life after my research at the Van Doesburg house in Paris when at that exact same time, the Yellow Vests Protests were happening outside. I felt like this was clearly one of these cycles. I have researched the Theo van Doesburg collection at the Centraal Museum and made a collection intervention there that brings together these two totally different moments in time; that both historicized the protests and contemporized the historical works.

The idea we had with Katerina Gregos and the exhibition curator Daphne Vitali at EMST was to look at how we can (re)activate different momentums. Therefore we decided to present an exhibition within the exhibition. “jaune, geel, gelb, yellow” is on a floor that presents a historical overview of artists from the 1950s onwards that form the political heart of the permanent collection. The concept is to open up the dialogue across the historical panorama of this specific floor and try to contemporize it, bring it back to our times, and relate it with actuality. That is precisely what I did. I believe that the installation succeeds in activating the whole space; not only the area of my conversation with Van Doesburg but also the surroundings, including iconic works like that of Jannis Kounellis.

I would love your collaboration for the next one — If I had to interview one artist, a friend of yours, for an upcoming issue of the “FEATURES” series, who would that be and why?

Laure Prouvost — I love her! She is a dear friend, and I admire her work. Of course, our artistic practices differ a lot, but what mesmerises me in her process is how the idiosyncratic can become collective in different ways.