Features #10 — August 2022

Camille Henrot in conversation with Nicolas Vamvouklis

Camille, I can’t help but ask you about the iconic film “Grosse Fatigue”, for which you were awarded the Silver Lion at the 55th Venice Biennale. You have probably received dozens of questions about its making. Still, I’m wondering how do you connect with this work after almost a decade?

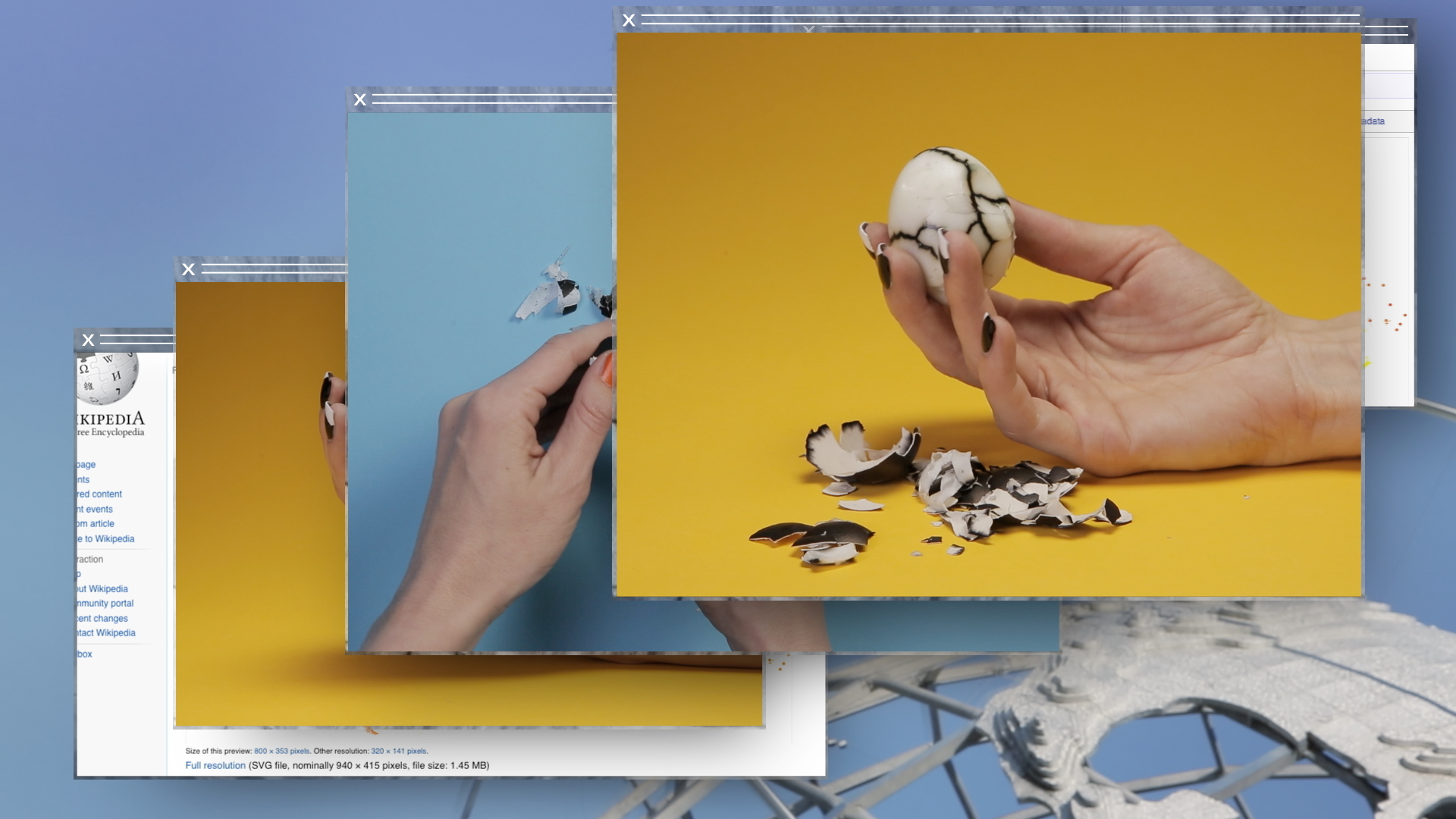

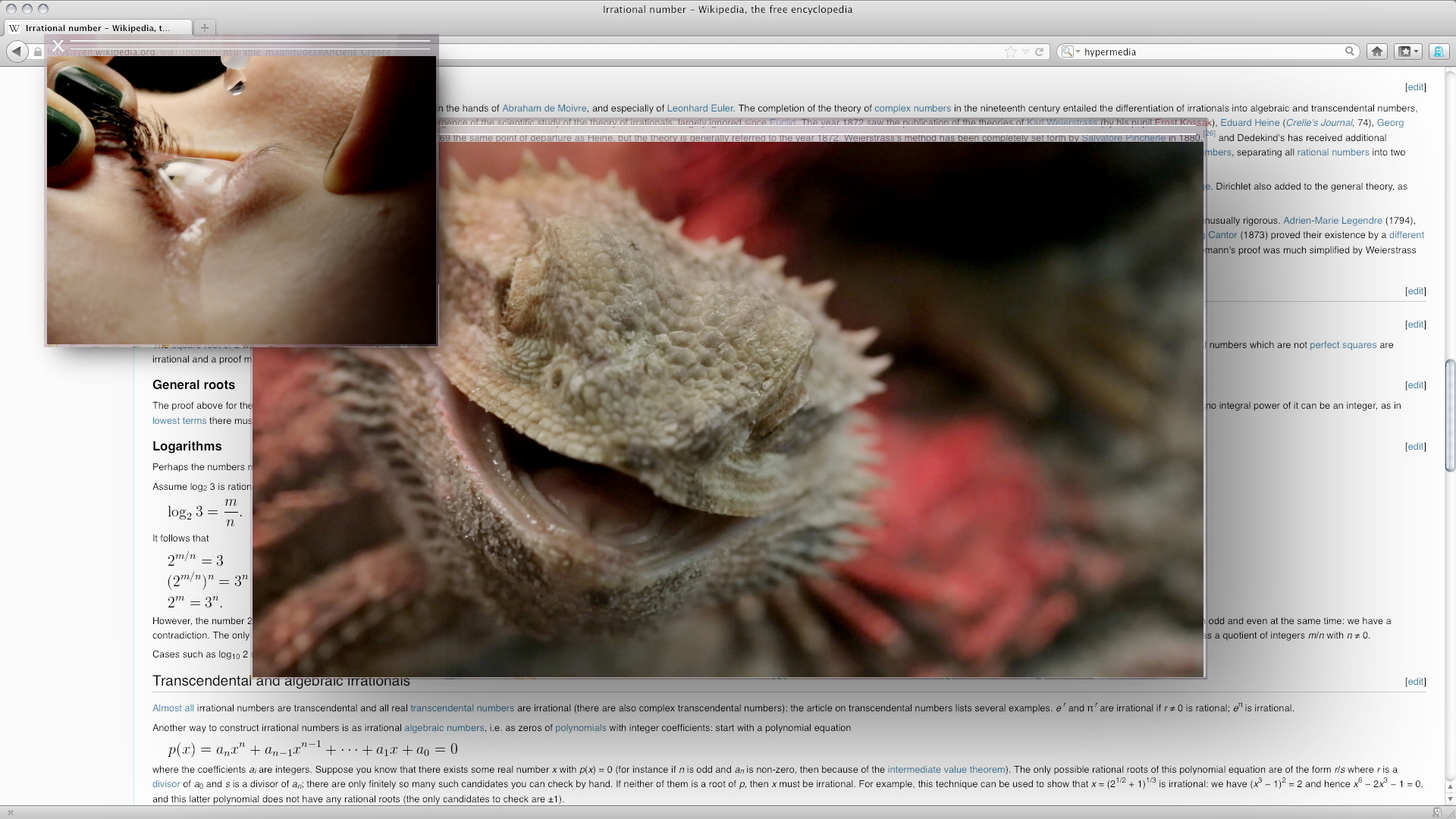

I reconnected with this work recently through my experience of the pandemic, where everything was heavily screen-based – personal research on top of planning on top of other websites… I think a lot of us face this suffocating overload of access to data. Too much information makes it impossible to read. The pandemic put our real lives and digital lives out of balance. The weight of the information we take in – news of authoritarian policies and politics feels even heavier because most of our lives are focused on or pulled towards social media. There’s an overwhelming sense of powerlessness. Things happen to us, and we feel complacent, like we cannot be drivers or actors in the process – especially within the climate crisis. The main motivation of “Grosse Fatigue” was to address the ways our society and culture seek to study nature and objects in the world through collecting artifacts and specimens. Along with a commitment to prevention and conservation, there’s a fascination with disappearance, rarity, and extinction that in a way contradicts the museum’s real mission, which should extend to the natural world. My generation and those younger than me feel that museums and institutions have to take on a leading role in regard to this topic and that the separation between nature and culture is not valid. I was really touched by the group of activists from ‘Just Stop Oil’ that glued themselves to famous artworks in museums – I found it to be an interesting strategy of disobedience because it invalidates that separation. That is what has been on my mind regarding “Grosse Fatigue.”

I also think of “Grosse Fatigue” as related to privacy issues – the articulation between private individuals and universal stories; what is specific and what is global. Even though I tried to address that problematic in the film, I would probably do the film differently today to make it clearer that the universalist approach is a failure. There is no possibility for just one story. The film is a collage of different stories I made, and the collage was a way to demonstrate that multiplicity. Still, the film is just one story. I’m curious to see how the film’s reception will evolve in sometimes anticipated ways – but also in ways that are not exactly in sync with common discourses.

It’s super exciting for me to see that other young artists, students, teachers, and critics are asking to see the film and use it as a reference in different art historical publications and online forums. At the time of the film’s production, it was rare to see a woman artist being centred for her work without her contribution being portrayed as coming from a ‘marginal’ place. I do see a lot of “Grosse Fatigue” babies – video art inspired by my work or maybe not at all… It’s not something I anticipated when I made the film, but in a way, it’s very natural that the film – being a product of such intense research about information overload and excess – has endless connections to both itself and other works. There are so many entry and exit points from it.

The film addresses the story of the Universe’s origin, which makes me curious about how important order is in your everyday life.

Finding order is a kind of art. One of the most anxiety-relieving art forms, if you can accept exceptions to the rule. Everyday life is a big source of inspiration for me, if not the only source. I think of everyday life as a library of books, some of which I choose and others that I don’t. I enjoy the chance encounters, and a lot of my work is trying to make sense of everyday life to build some sort of continuity. I think it’s also a mental characteristic that I have – where everything has to make sense; otherwise, nothing makes sense. The person you meet while you walk your dog, the book you’ve been reading, followed by the menu at the restaurant, and a conversation with a friend all funnel into one thread. The creative drive comes from a desire or impulse to collect and unify the scattered narratives of our days.

Speaking about libraries, you have lately participated in “Fore-Edge Painting,” a special double-exhibition hosted by MACRO and Bibliotheca Hertziana: eight visual artists were invited to transform selected volumes into artworks. Could you tell me a bit about your intervention?

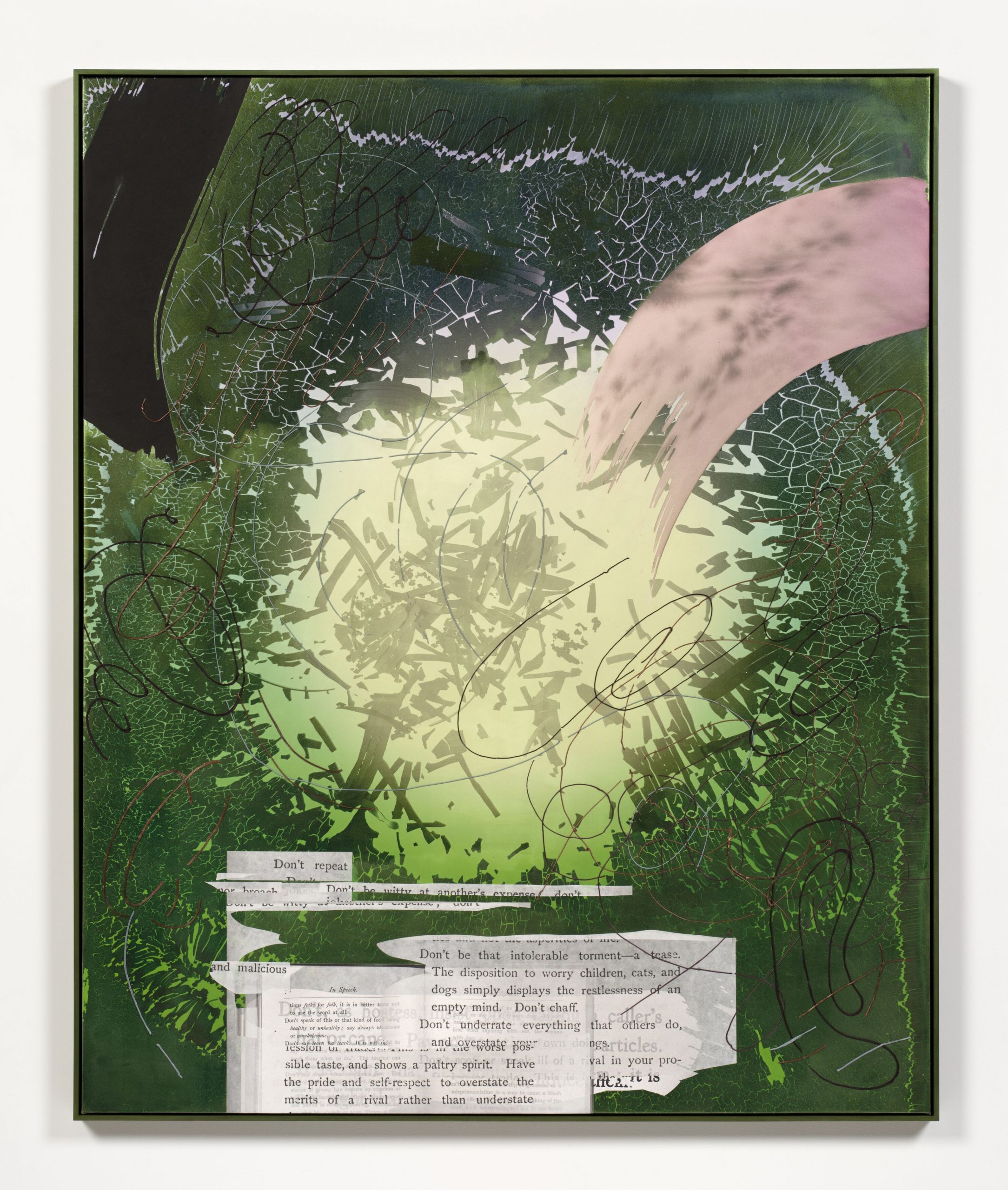

The exhibition was a proposal from my friend and curator Luca Lo Pinto. I immediately felt enthusiastic about the project because of the idea that the painted image gets fragmented by every single page, but all together, the pages of the book constitute one image. That concept is fascinating to me. I decided to select a large encyclopedia, because it has a really thick spine (and therefore painting surface) and because it’s outdated – sort of like an ancestor of the internet. The figures that I painted are sphinxes. They guarded passageways to ancient cities, preventing whoever could not answer their riddles from entering. They literally prevent access but also retain the entirety of knowledge and wisdom; of answers to questions that are not easily solved. They play with revelation and concealment of information, just like opening and closing a book. One of the paintings is a series of claw marks, as if the book was handled by the sphinx itself. The other paintings show sphinxes attached to each other by a leash. That restraint stands in opposition to the idea that knowledge is freeing. I think it can be both liberating and alienating at the same time.

I thought it was a great exhibition. Bibliotheca Hertziana also fascinates me with its baroque entrance that represents the mouth of the monster. It’s like you enter the digestive system of the library – like a return to the belly.

I know you are a proud bibliophile; do you collect any other kinds of objects?

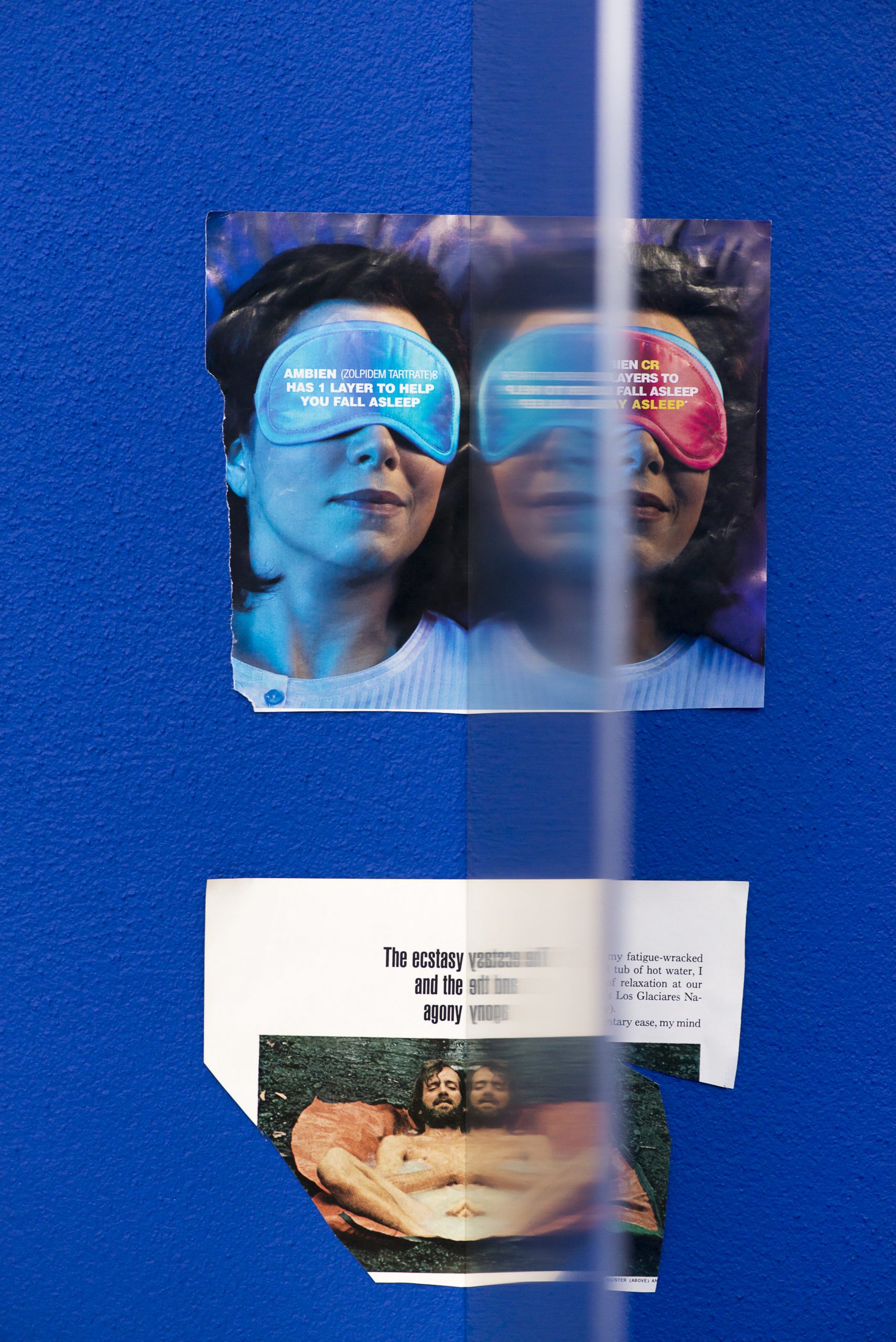

I used to collect a lot of postcards when I was a child. I was collecting so many things – dog figurines, books about horses, miniature bottles, miniature erasers, stamps. I had a recurring thought that if there was a fire, my collection of stamps would be the first thing I would save. I was convinced it was super precious and that it would make me rich. I remember the vortex of questions I had – how to organize them, by country, by type of illustration, or by price… As a kid, you have so little control over your environment, and I think sometimes you don’t know where to put things. My son sometimes gets worried when I touch his things. He asks me to tell everyone in the house not to touch his toy trains. Moyra Davey writes convincingly about that fear of losing order in “Index Cards.” There’s a fear of losing and a joy of finding as well. I’m constantly trying to declutter my home, but I think I just like to dive into the mess more than anything. Attempting to reorder is also just an excuse to experience chance encounters for me. I still keep postcards; I have a huge collection now. In the past, I used them like question cards when I was seeking to learn about art history and the world. Now I collect more digital stuff… screenshots, reference images, etc.

A couple of years ago, I curated the “Sleeping with a tiger” exhibition in Lesvos, inspired by the oeuvre of Maria Lassnig. I was excited to find out that you have also made a body of paper works as an homage to the Austrian painter. In which ways do you relate with other artists’ processes?

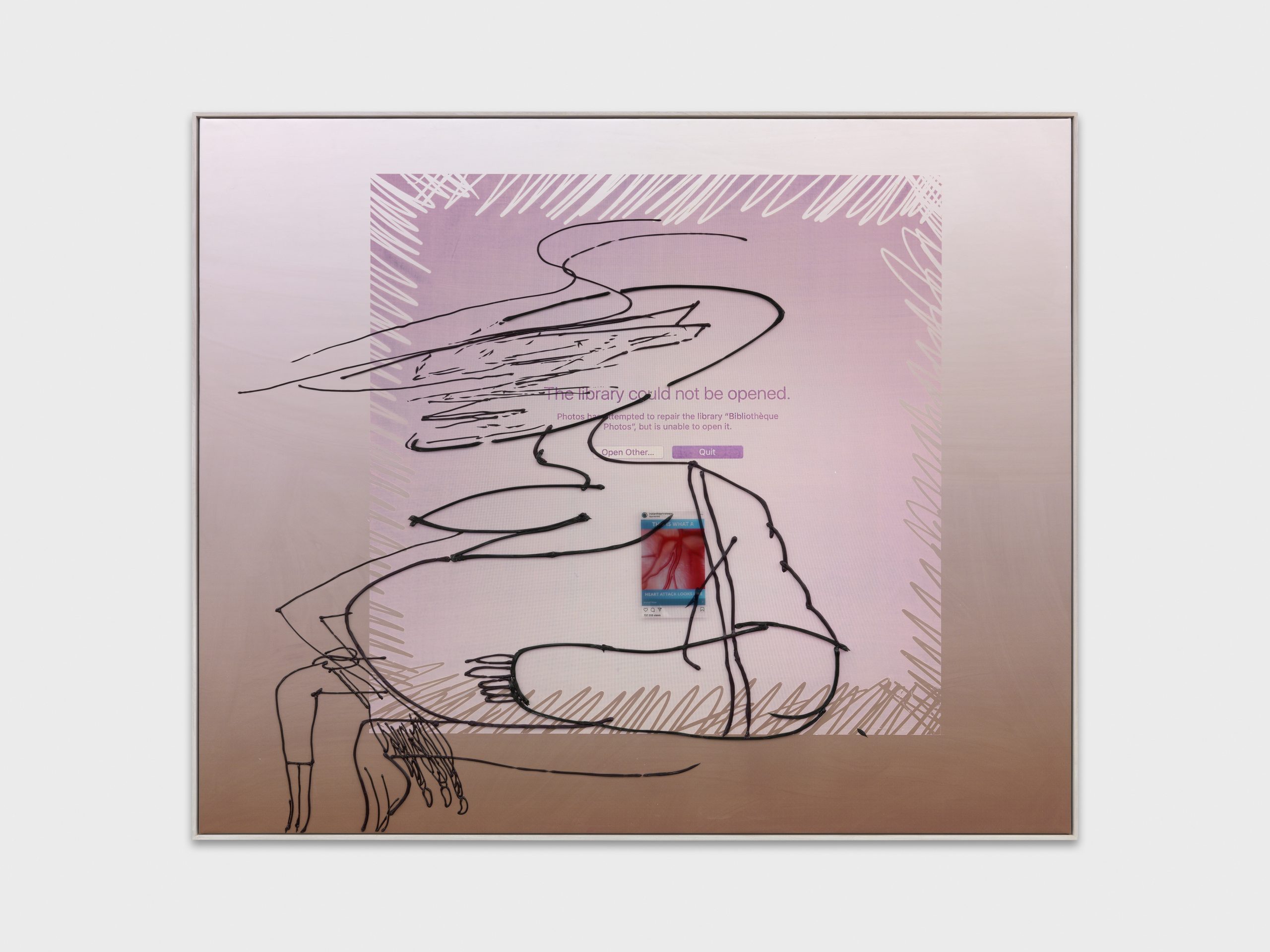

I spend a lot of time collecting reference images, and for different series of works, I put them all in large binders. Maria Lassnig is always a recurring reference for me; she reappears throughout all my binders. Especially when I started painting, I think I was very insecure, and Maria Lassnig was one of the artists who helped me feel confident in my ability. Picasso was also a big influence in terms of the importance of the line. Steinberg, the cartoonist, is also a big inspiration. It’s rare that I obsess over one artist. I prefer to have seen one image but not to know too much about it. My references are all very random and fragmented. When painting, I try to connect them with the stories they are telling, like some sort of divination process or card game. Only when they are all together in front of me, and I’ve been marinating in them, do my references come together. I never really work specifically from one image. I love the idea that one can be ‘pregnant with ideas.’ When painting, I like to feel ‘pregnant with images.’

I really love this pregnancy metaphor, which naturally leads me to the last question. Ben Eastham mentioned that your 2015 “Minor Concerns” seek to reclaim the routine indignities our lives are replete with. What would you draw today if you had to add one more piece to this series?

I would definitely add the frustration that comes from bad internet connections. I would draw the digital dinosaur that appears when a webpage cannot be found. Living with children, there are a million situations I could add: being puked on, being peed on… and ‘no babysitter’ is the new version of ‘no battery.’