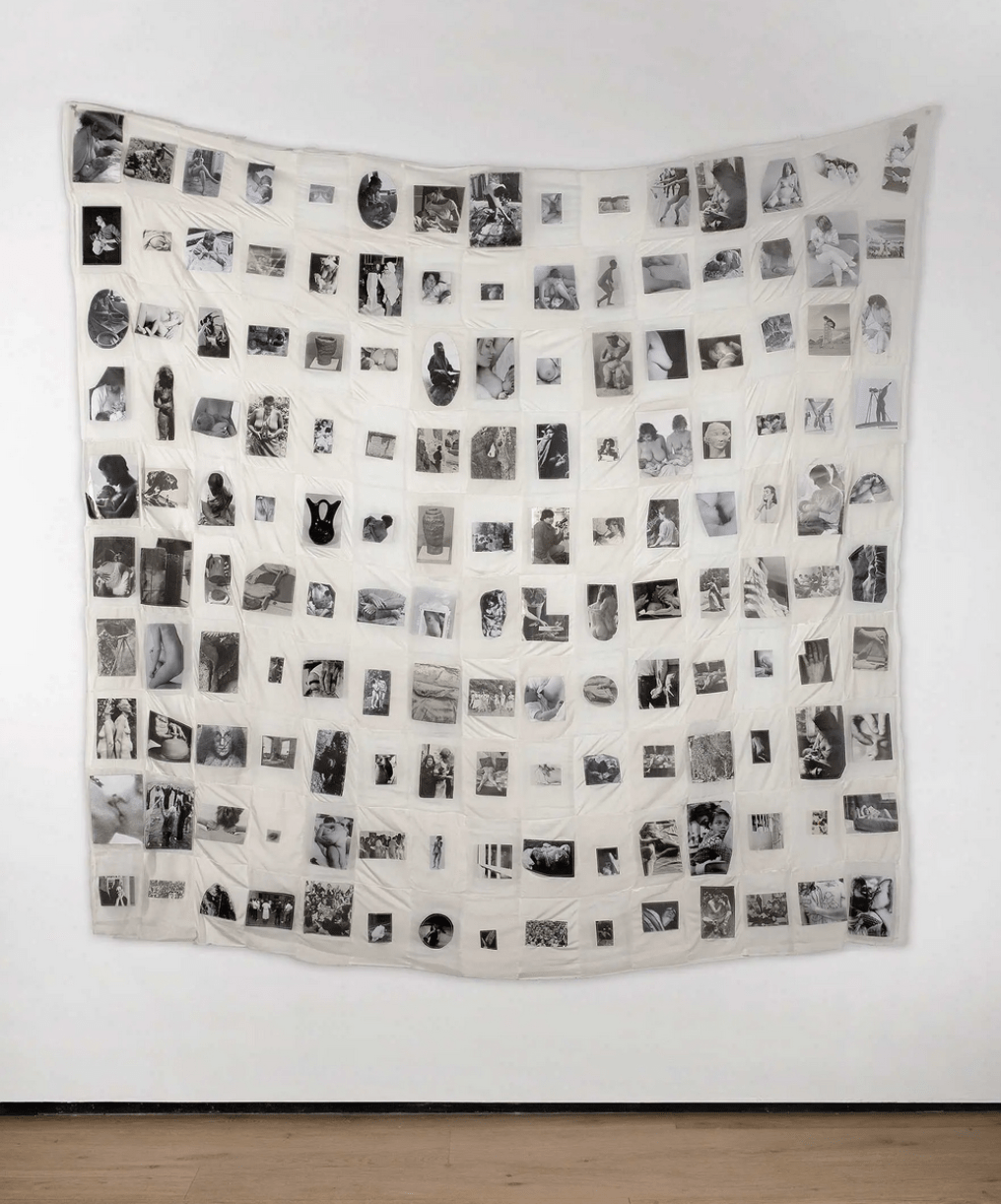

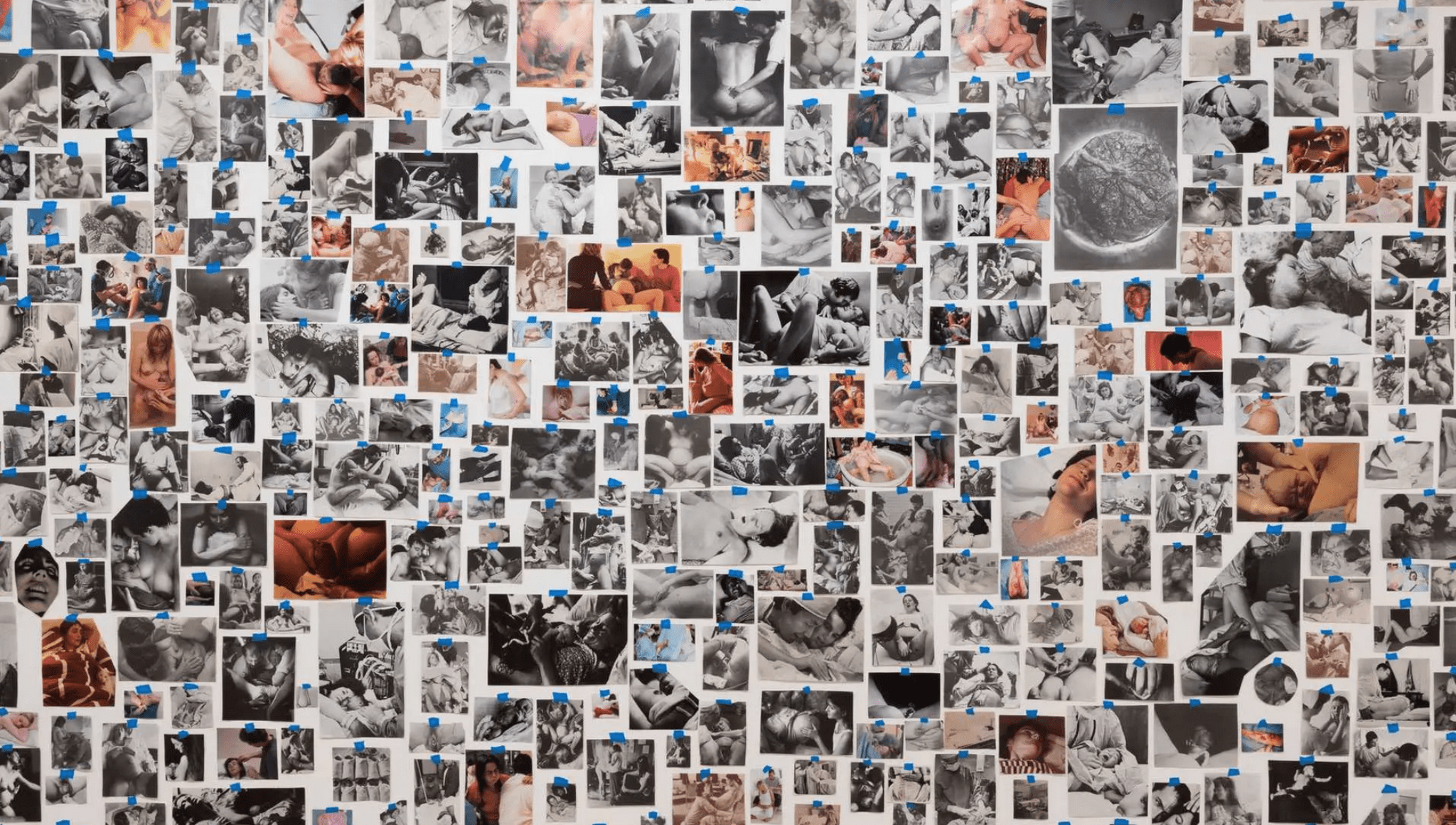

In 2018, with the installation My Birth, she papered the walls of New York’s MoMA with more than 2,000 images of women about to give birth. Vintage photographs, images retrieved from old books and magazines are the result of research and archiving work that takes her around the United States of America hunting for used volumes from which she can draw material to cut out and reassemble into large puzzles with no beginning or end. If photography is an enigma, Carmen Winant creates surprising ones. Her works are statements of intent, conceptual maps in which the woman’s body is always the protagonist, and the viewer can reread our history from a feminist perspective. The viewer’s work is a path of interpretation and creation of new associations, free, personal, circular, sometimes contradictory.

The indications for reading seem encapsulated in the titles: Woman must write herself; The answer is matriarchy; The history of my pleasure; The last safe abortion – the latter presented in August at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The stories of each are threads of a shared history; birth is a collective fact, as it is pleasure, pain, joy. The body becomes the vector and endpoint of an artistic practice that is first and foremost a political act, because it develops within networks of individuals, and is the result of exchanges, discussions, and relationships.

Like an archaeologist, Carmen Winant retrieves material from the past and reinvents the present, relying on a process of re-signification that forces us to reflect on major issues such as gender equality, the right to abortion, and the affirmation of women in a patriarchal world.

In July we met on Zoom to talk about her work while Winant was in Santa Barbara, California, at her parents’ home.

Good morning, Carmen. Let’s start from the beginning: how did you get started working with images?

I really fell in love with photography when I was in high school and I was interested in other people’s images already at the time. I used to tape many pictures to my walls, like many teenagers do. Layers upon layers, like archaeological stratifications. When my parents moved out from that house, they struggled to peel everything off the walls. In college, I chose to study photography for that reason, but I was really convinced that I had to take my own pictures, and that this was the only way to become a “serious” artist. So I did that for many years, and as it so often goes I kind of slowly came back around to what I was in love with as a teenager. To a way of looking at pictures, of working with images. So I started taking pictures of other people’s pictures and then I finally started to move my own camera aside and kind of let go of the idea that I had to make something original. Whatever that means. As for why photography at all: it’s hard to say why we feel compelled to go in the directions we go, but for me it was something I felt from a very young age.

Are you a tidy person? How do you store and organize in a functional way all your materials?

I am laughing because I am – and if my husband was here he would laugh at that question – because I am wildly disorganized, I am chaotic both in my home life and in my studio life. I once saw a video online about John Baldessari’s studio and it was organized so immaculately, every little draw labeled! A part of me feels “oh my God, I would love to operate that way! It would be much more efficient”, and another part of me that feels that it’s the studio mess and the studio chaos that creates sort of new affinities. These piles that literally kind of fall into each other. For years I didn’t work at actually any table in the studio and I would just spread everything out on the floor and move things around that way. It is as if, by returning to work the way I did as a teenager, I could rekindle my impulses, and a way of working that is already within me.. Like it was when I was young, when I wanted to see everything all at once and I didn’t want to be too systematic, because I thought that it would lead to a kind of rigidity. And, of course, this is not a judgment, this is simply what applies to myself. And I have reached a kind of… let’s call it a “semi-organized” chaos.

Where is your studio?

My studio is at home, actually. When my kids were babies – now they are 7 and 5 years old – I converted my garage into my studio, so that I could put them down to take a nap and work, or work in the evening, whatever the case. My husband is also an artist, and he also has his studio at home, and that system has worked great. I might need to change the system soon enough but that feels like an important element to mention, because I try, whenever I am talking about my work, to talk about my family life as well, of the configuration of it, of being a mother and all of all that it entails. Those things are not separate, even simplystructurally. So yes, my studio is at home, just a few feet away from my children’s bedroom.

You just said you can’t separate art and life. Your art is an excavating work and your artworks are mighty, encyclopedic, they look like endless works, like “Body/Index”. You start from big themes like birth or pleasure and you develop them through very rich and articulate visual paths, with archival images and clippings from books and newspapers. There is always this centrality of body and gestures. Why is the body so central to your research?

I would say I’ve always been interested in feminist politics, since I was quite young. It’s hard to identify where we get affinities and identifications from. I think this comes from my mother. Of course, as someone like Sara Ahmed could say, feminism is in your body, it is not an abstract, ideological idea exclusively, it is something that actually lives inside of us. I have always felt that way. She describes it like our skin and our breath. I have always been interested in the historical and ideological level but also in the phenomenological level, and in other levels, of our bodies and ourselves. Another thing I usually don’t talk about is that for ten years – from when I was 12 through my early twenties–I was a competitive long-distance runner and that was a central and driving force in my life, much more than art. I hoped to be an Olympian, I was a very serious runner. I think I have developed real body intelligence through that, and body logic. So when I started to transition towards making art, I already knew how to process things through my body and take all my body’s processes seriously. I don’t often talk about that because it doesn’t feel so directly related on the surface, but deep down it feels quite related. I think it is important to say that all of this doesn’t just mean relating to an historical idea – both as it comes to feminism and, in my case, as it comes to Athletics – but it also means relating to one’s own body and to the world, to ecstasy and pleasure, to agony and to exhaustion, and to failure. My own body. That feels like an important background. Whether it is useful for this conversation or not, I am not sure.

What does it mean to be a feminist artist today, concretely?

[As for my sense of being a feminist artist] I often feel like my work is a sort of engine for my feminism, it is the way in which my feminism is expressed. It governs the way I live my life, the way I am a mother, or a neighbor or an educator, or whatever else. As for my particular brand of feminism, I am in a different context than you, here in the United States, but I often feel a little bit out of depth with what is hip, in terms of the third wave of feminism or the fourth way of feminism or whatever we are in now. I consider myself to be like a radical feminist. That may be considered an outdated term or even an outdated ideology, but I really align myself with a kind of a burned-down feminism, which is just saying that I am not so interested in making compromises, I think that the patriarchy and capitalism are incompatible with feminism, I don’t think that these are things that can actually exist at the same time. Even if it is speculative, I really am aligned with other artists, and particularly with thinkers and writers and critics who are interested in imagining another world. And, again, even if it is just speculative, I think that it is really important to hold on to this idea that another world is possible, and is viable. That’s so hard now – now perhaps more than ever – but for me my feminist politics has to be glued to that. And it can’t become like a slogan on a t-shirt.

Maybe, more substantively, I work with images that not only depict feminist coalitions and feminist acts, but that are themselves sourced from feminist literature and feminist organizations. In doing so, there is a whole other social component of my work that is not otherwise visible, like in the project about domestic violence for instance, even for the birth project.

To collect those kinds of images means getting to know people and often working intergenerationally with feminists who are much older than me, not just to collect that material, but to build those relationships. That is a part of the work too, and it isn’t otherwise available in a photograph or in an exhibition. That part is maybe a little bit more obvious, I guess, but that is the subject of the work as much as the strategy.

How do you find all the materials – books, photographs – you work with?

This has changed over time. I used to only collect material that I would actually find in the world: in bookstores, in garage sales, state sales, never buying anything online. I gave myself this rule that I had to physically touch the material if I was going to bring them into the studio. And then, once I had children, I couldn’t move about in the same way and make the same kind of pilgrimages, so I refined my strategies and I started to figure out how to collect online and now, more and more, I have moved to working with existing archives. I guess we can call them institutional archives: in museums, libraries, universities and also smaller organizations. I never thought I would do it, and it seemed to me like a very conservative way of working, when I first started. I have done that in large part because it is practical but also because I think about the ethics of working this way and appropriating other people’s photographs. There is no a pure way to be an artist, ethically speaking, but I did feel there was a kind of internal conflict there, that I couldn’t quite resolve. Sometimes people would find a photograph in one of my works, like My Birth, and be thrilled and sometimes not so much. As I mentioned, working in this way with an organization, like those domestic violence organizations, means that I am building relationships in a different way. So it’s a combination of those things that has enabled me to start to shift and evolve, to research and collect. And a final example that I will give of that is a project that I just finished for the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It is about abortion care providers, which in this country has gone to shit. That means going to clinics, using the feminist network I have, introducing myself and asking for their trust, looking through their pictures, and using them, and doing that with ten different clinics. That’s such a different process then being alone in my studio and buying books on the internet and cutting them up. Again, there is not right and wrong, but it is sort of exciting and scary to shift, and to work with images in a similar way but what is so different is how they come in.

Can you explain your creative process? When they give you these books and materials do you cut them or do you reproduce and photograph them?

It varies. For instance, with the Domestic violence project, I worked with no profit organizations. They are not big fancy institutions, and they just let me use their materials, so I used their primary materials in the exhibition. While in this Abortion project, all of the photographs that I am using are 4 by 6 inches, and I am scanning all of them and then reprinting them as 4 by 6 inches, so they are like fac similes. So the process varies from project to project because I am interested in working with the primary object, but I have to be flexible. I am learning to be flexible.

As for your exhibitions, do you imagine and design your installations alone or do you have a team and/or do you collaborate with someone?

Good question. I think of them as sort of soft collaborators. I have been so lucky in these projects! Well I guess it’s not just luck: you find people with the same mindset.

About these smart feminist curators I have been lucky to work with – around the country and internationally – I feel we found each other, and then the conversation often sort of evolved together. I tried to make new work for every project, so that implies a lot of conversations… I have this material, what should I do with it? And this is also the case for my artist books. We kind of build them together from the ground up. So those people are often credited in the way that they should be. I don’t think of myself ever as working alone. I don’t have an assistant but I am in a network of people I work with. It’s a kind of collective process. I am thinking more and more about how to name people, it’s in the spirit of the work itself, which is like a kind of collective identity, a kind of coalition building. I sometimes have somebody into the studio, project by project, to help me to build something. Sometimes it’s the curator who is in conversation with me, or the friend who comes over to do five studio visits. It’s like thinking about the making of the work as existing beyond one person.

Is there an artist or a person who particularly inspired you?

When I was an undergrad at UCLA, my first photo class was with Catherine Opie, the photographer, and that really blew my world open. She was so generous as a teacher, one of the few influences like that. She contributed to the Domestic violence book. I worked for her after college, what an incredible luck to learn from her, and continue to learn from her across those years.

And which was your first “important” exhibition?

There has been no project for me like My Birth. That project and exhibition really cracked things open for me, both in terms of the number of people who saw it, and how visible it was. I wasn’t sure what would happen: if people would respond to it or feel horrified by it. And, separately from its visibility, it really changed what I thought as my practice, like what my practice could be, and what it could be about, how I could operate. It was a really important turning point for me, and we don’t get many of those, as artists. So I am really grateful to Lucy Gallun, the curator of that show who really encouraged me. I tried to back out multiple times but she really encouraged me to just stay the course. These are keystone people and exhibition to me.

How do you store and archive all the material of the exhibitions? Are they part of a collection, or do you keep them in your studio?

It varies. It’s always nice when a museum acquires it, because they can take care of it. MoMa acquired that work (My Birth) and it was such a headache for them to figure out how to do it. They ended up storing it in sort of sheets of archival papers, they taped each one down and then they stocked all them in archival boxes in the freezer. Which is so funny because in the studio I am like walking on them. Others come back to me in boxes, but I don’t have a lot of them in the studio, most of them are now out in the world. Ultimately, I think they are precious but they are pieces of paper, so I never feel as high pressure as the conservators.

PHOTO CREDITS

My Birth (detail), MoMA, NY, 2018

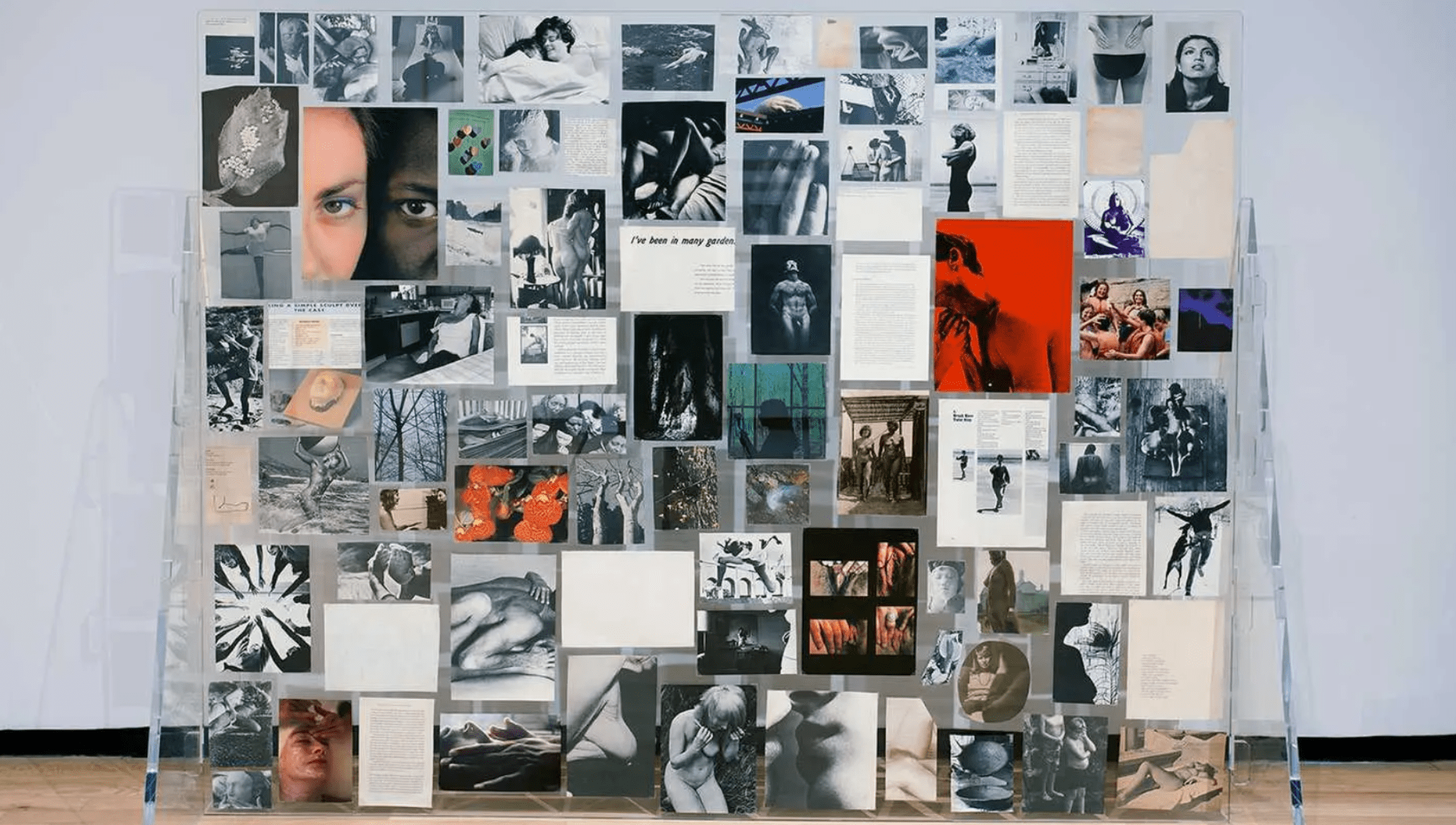

Arrangements, Images Vevey, Switzerland, 2022

A Woman Must Write Herself, Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, 2019

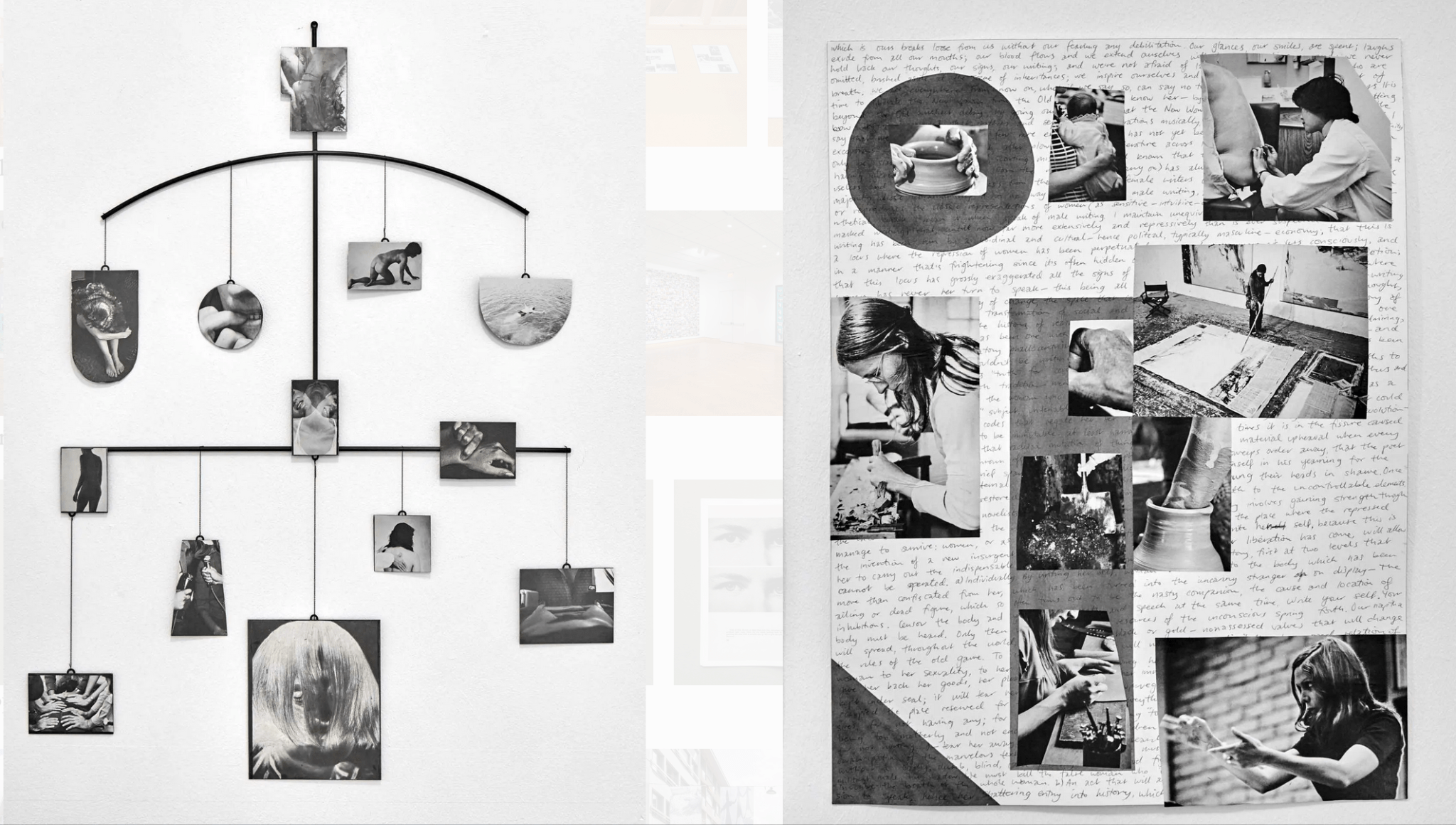

The History of My Pleasure, Museum of Contemoporary Photography, Chicago, 2021

The Answer is Matriachy, Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio, 2017

The History of My Pleasure, 14a Gallery, Hamburg, GR, 2019

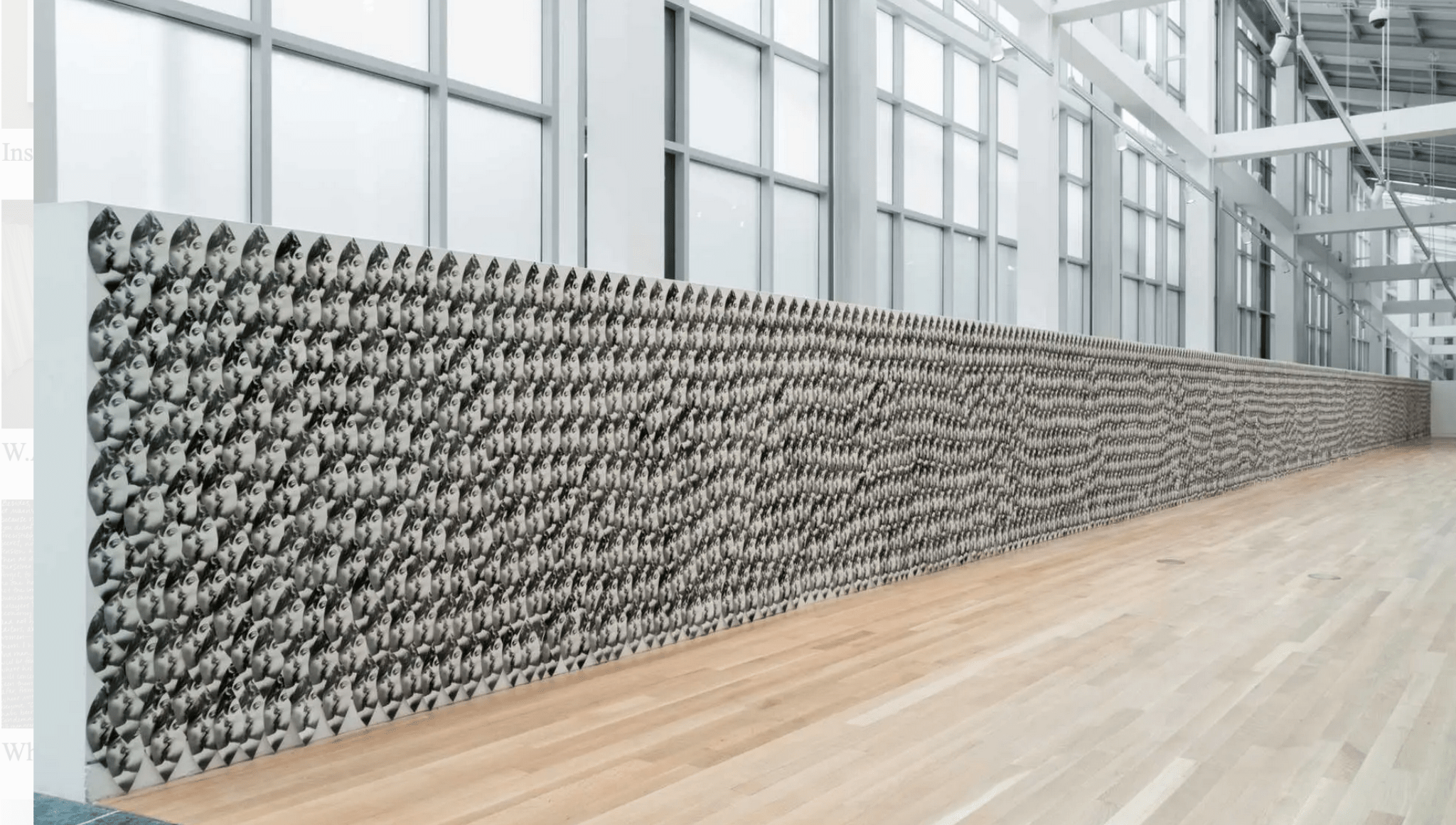

Looking Forward to Being Attacked (detail), Sculpture Center, NY, 2018

Looking Forward to Being Attacked, Sculpture Center, NY, 2018

The last safe abortion, MIA, Minneapolis, 2023

XYZ-SOB-ABC, Contact photo festival, Canada, 2019

XYZ-SOB-ABC, Contact photo festival 3, Canada, 2019

Consiousness Raising, Bemis Center, Nebraska, 2022

XYZ-SOB-ABC, Contact photo festival 2, Canada, 2019

XYZ-SOB-ABC, Contact photo festival 4, Canada, 2019

My Birth, MoMA, NY, 2018