The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes Awww!

– Jack Kerouac, On the Road

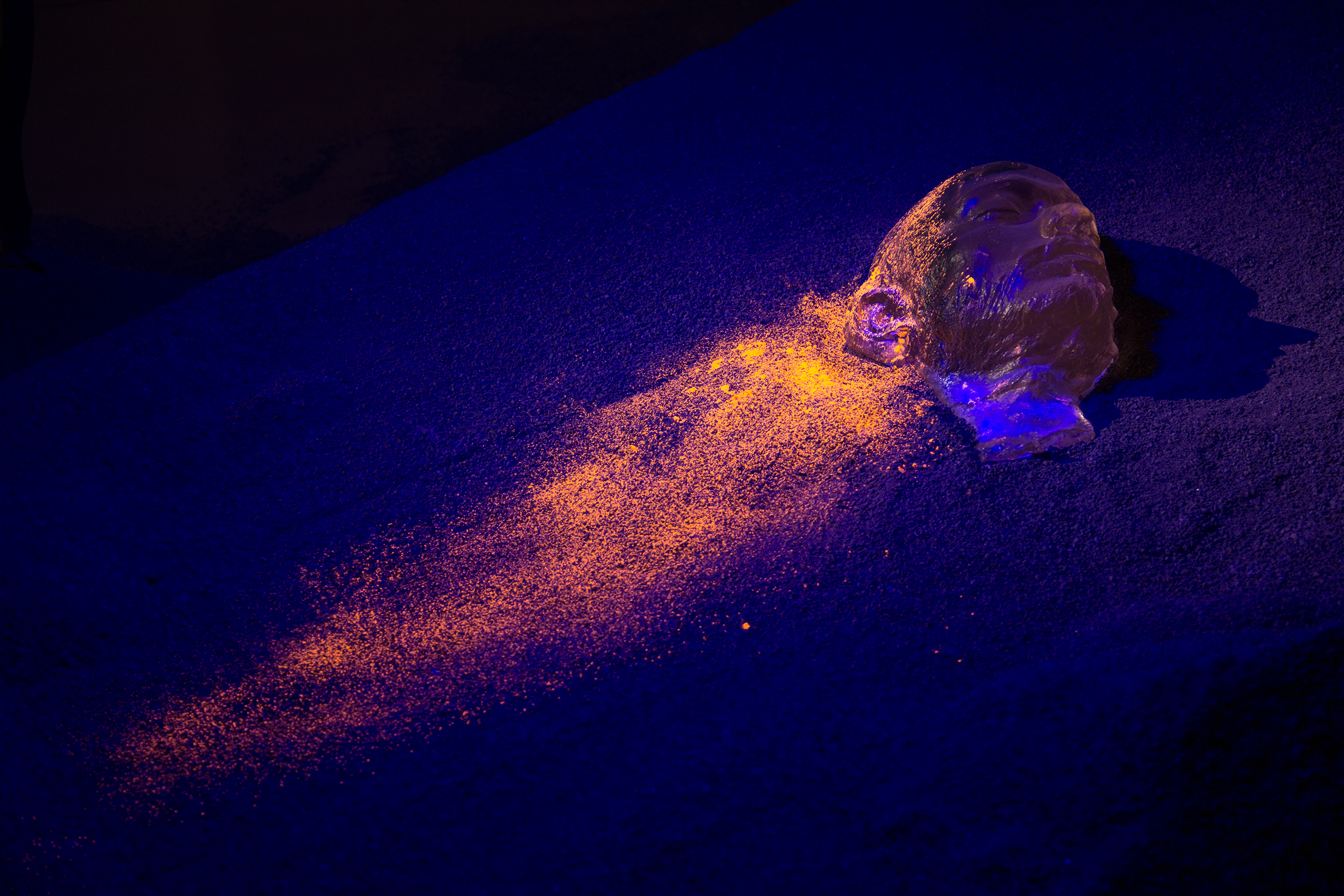

During the pandemic period, you worked on the project Pneuma, with which you won the 6th edition of the Italian Council prize. The project tells about the condition of immateriality and intangibility of mental illnesses: a topic that has become more topical than ever given the psychological impact of the pandemic on people, and which is still awaiting adequate space for an in-depth study. Your research has always focused on de-stigmatizing the idea of mental illness, investigating how economic, political, and social systems define an individual as “abnormal” according to their social attitudes.

The project, in particular, raises questions about the treatment of mental distress in Europe, and began with a series of workshops in 10 countries (Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the UK, Romania, and the Czech Republic) meeting doctors and health personnel, people in care and other social actors. Over this last year the conditions imposed by the pandemic have dramatically changed people’s lives. What has changed from the initial project during this time? What sort of new implications this type of project can have now?

The issues that I address in my work have proven to be extremely relevant in light of the events that have occurred since March 2020. The Pneuma project has confronted the global emergency, not only from the point of view of content, but also from that of the exhibition, of the audience, of meeting people and with its dissemination.

It is a project that raises some questions and issues about open problems that concern society and the individual who lives in it. Issues such as forced and voluntary isolation and marginalisation, which have become more tangible since the outbreak of the pandemic and have touched the population of the entire world.

PNEUMA TRAILER OF THE VIDEO

In spite of the restrictions on travel and the impact of the pandemic on the various exhibition programmes, you have already managed to present this project in partial form in several places, namely STATE Studio Experience Science in Berlin, MARe Museum in Bucharest, Löwenbräukunst Contemporary Art Center and schwarzescafé in Zurich, Etablissement Gschwandner Reaktor in Vienna, and La Fondazione in Rome.

The Italian Council is therefore proving, despite the current climate, a valuable opportunity to “travel” and make the research and the works of contemporary Italian artists known abroad. What is your opinion on this award as an instrument to support contemporary Italian art?

In recent years, the General Directorate for Contemporary Creativity has launched various initiatives for the support and diffusion of Italian art at an international level, and the Italian Council is its most effective and most prestigious tool. Today it incorporates many different possibilities and proposals. The one I focused on with my project is the one dedicated to the increase of Italian public collections and project promotion at an international level, and certainly this focus is also the most challenging from all points of view as it must include preliminary research, production, promotion, diffusion, and economic management.

ARTWORKS

This period has been a great time of reflection for everyone, also regarding the role we can play within society.

Your project, maybe unpredictably, has acquired along the way a much more relevant social meaning and historical relevance. How can artists contribute to a deeper understanding of this difficult period?

Certainly the personal reflections of artists over the past year have been multiple, and they have largely dwelt, as you said, on the role that the artist can have in society, as well as in the labour market and whether this role really is acknowledged in its relevance and dignity. Unfortunately, from this collective experience, many of the problems and negative points that still exist in the cultural and art sector have emerged, especially the ones related to the role of the artist as a professional worker.

In many cases from the great rubble come great rebirths and new life bloods.

The artist who works with a primarily selfish interest will continue in any situation, even the most dramatic ones, to experiment, conceive and work. It will then be the role of history, with its method often paradoxical, chaotic and random, to determine who will be recognised as such.