Francesco Arena in conversation with Mattia Solari

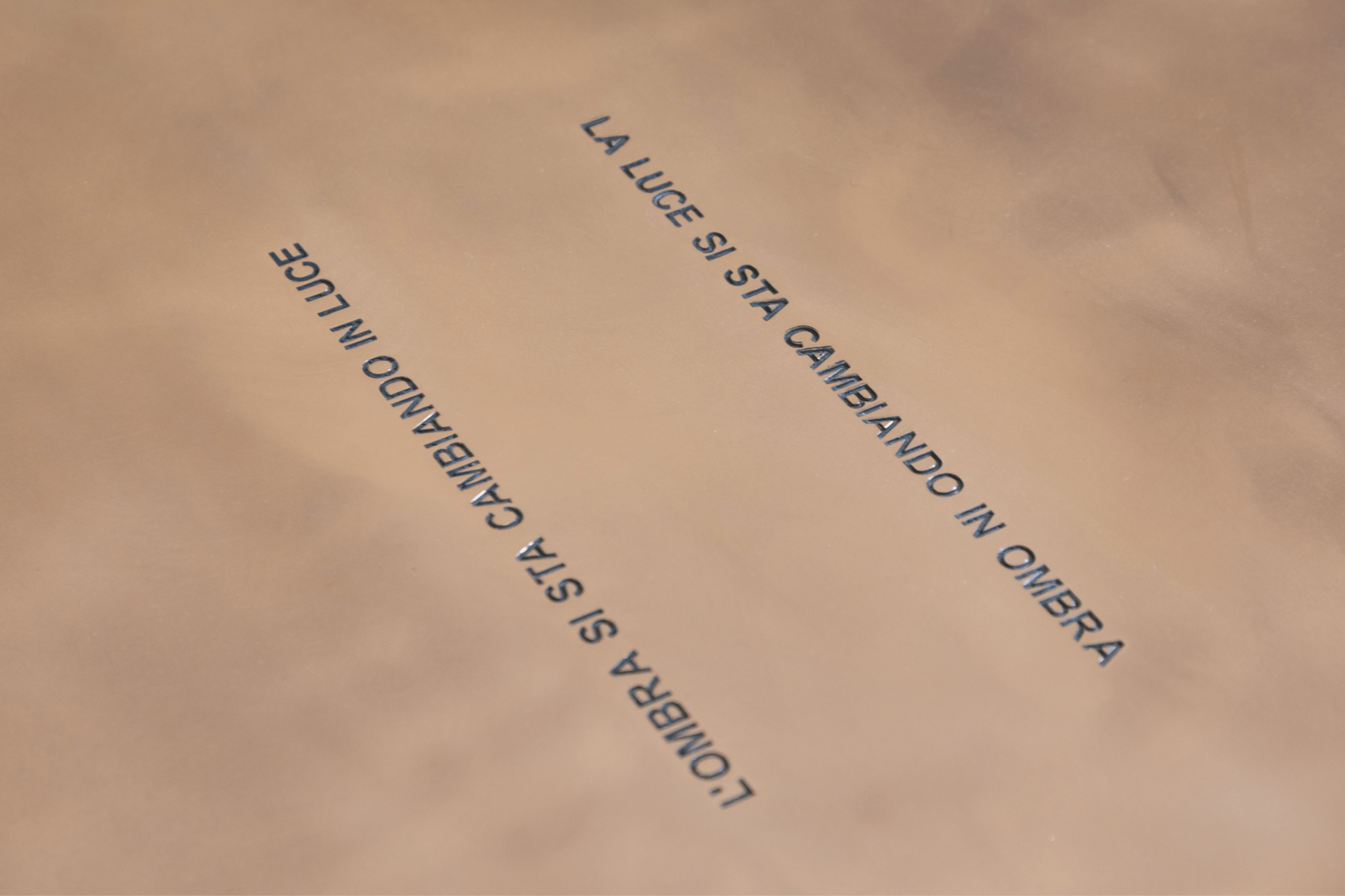

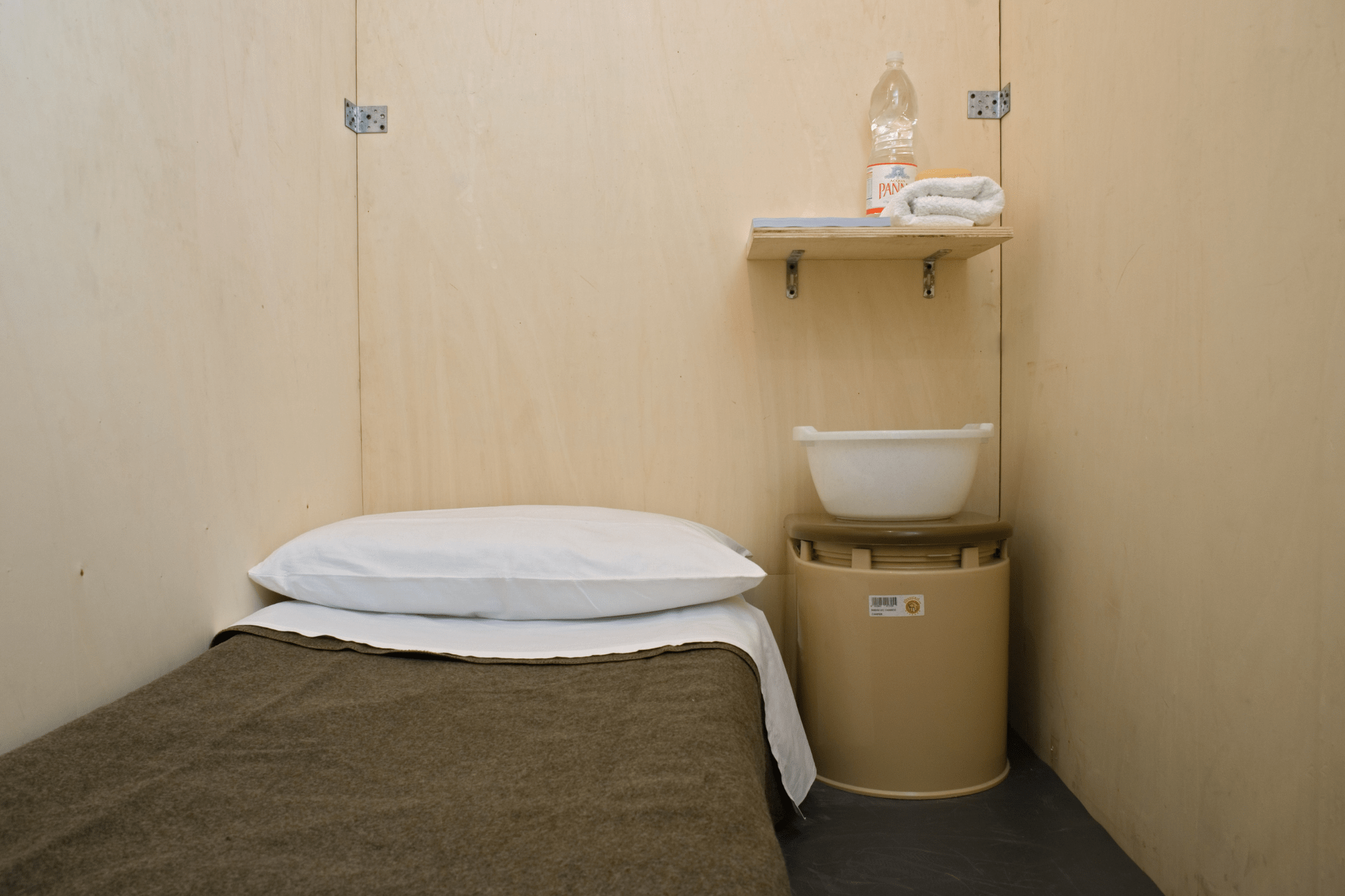

I would start by asking you about the work on show in the exhibition, Letto per i giorni e le notti (Bed for Days and Nights). Here you retrieve a bed from the old prison in Procida and add a copper plate on which you engrave the phrase “Light is changing into shadow” and its inverse, “Shadow is changing into light.” These two phrases, as in a circular motion, chase each other replicating the sense of the monotonous alternation of day and night, a continuous present from which there seems to be no escape. Do you think there is a way to break this recurrence, to break out of the eternal return? Perhaps through sleep and dreaming? And more generally, I would like to ask you to tell us a little bit about how the artwork and its formalization (the copper plate, the quotation from Del Giudice’s novel, the recycling of a found object) came about?

The bed frame comes from Procida’s prison, Palazzo d’Avalos, which remained operational until the 1970s. When it was closed, everything remained as it was. That prison is a place where time stopped at that time, only the natural time of decay continued its course. Everything that remained in there: uniforms, shoes, furnishings, recorded the passage of time. When I visited the prison I thought that these beds were the only intimate places for inmates, as in all facilities like prisons, hospitals and barracks everything is shared all the time. The bed is the only truly private space, the only space of escape. An escape reached through sleep, dreaming, oblivion. I encountered the sentence engraved on the copper plate a few years ago in Daniele Del Giudice’s short novel “In the Museum of Reims,” which tells of this man who visits the museum to see artworks before he becomes completely blind and thus keeps the memory of them forever. There he meets a woman who helps him decipher the works and colors. In one passage she says that light turns into shadow, and that is what happens every day, with sunrises and sunsets; so I thought of the cyclical nature of everyday life that is insensitive to human events. Every day the natural cycle of events flows regardless of what happens to the humans who witness it. This sentence is engraved on the copper plate, chosen precisely because it is a durable yet human metal because it conveys warmth and energy. This, like all my works, does not come into being in a linear fashion, but is always a tangle of suggestions that are organized and take shape.

In your practice you choose stories, sometimes still unclear today, from the Italian political history of the 1970s and 1980s; I think of 92 centimetri su oggetti (la ringhiera di Pinelli) (92 centimeters on objects (Pinelli’s railing)) or 3,24mq (3.24sqm), which reconstructs the room where Aldo Moro was imprisoned. In these, as in many other works, you start from the numerical datum and then reflect on the historical consciousness of those events. Do you think about your work more as a commentary on those events, an artistic document or a (counter)narrative? In short, how do you frame your artistic agency?

These two works start from a specific fact of particular stories. They are works from a few years ago, over time I have moved away from such particular stories to embrace less specific and individual facts even though when I chose these figures, Moro and Pinelli, they interested me because I think they are characters that represented something beyond themselves, like when someone becomes emblematic of something in spite of himself. For example, I think that Pinelli wanted everything but to end up being “the anarchist Pinelli” by dying in that way. But history changes things, so a man loses his biographical data to become a state of mind, this is the case with these characters. Associating such controversial stories, still seeking explanations, with the numerical datum helps us to perceive something better. We are a body, we occupy a space, consequently, sometimes perceiving something not only through concept but also through physical experience, linked to tangibility, to measurement, can help us get closer to that story or what that story represents. Then the question of numerical data has stayed with me because it is one of my obsessions, it is part of my way of looking at things.

In other works you have dealt more openly with the theme of war and military life, I am thinking of Cratere (Crater), presented in 2010 at Vleeshal Center for Contemporary Art in Middelburg in the Netherlands, or, among your early works in Divisa mimetica nel vuoto di un’aureola (Mimetic Uniform in the Void of a Halo) or o Razione K nel vuoto di un’aureola (K Ration in the Void of a Halo), 2008. How does art deal with destruction, conflict, and militarism? Have you ever found an answer to that famous “what to do?”, the aporetic dilemma that from Lenin to Mario Merz returns in so many political and artistic reflections.

These two works are the same, although one is very large and the other very small. Sculpture is a space, a body occupying space, and these two works serve to fill a void. The K ration fills the void of the halo, organizes itself to stay in balance, the everydayness of the K ration, the meal of a soldier on a mission, organizes itself in this sacred space of the void surrounding the saint’s head. This sacred void is filled by the daily necessity of eating. The crater, on the other hand, is another attempt to fill a void. The work was made in Middelburg in the Netherlands. While researching for the exhibition, I saw that the town was heavily bombed during World War II, and I found a picture of a large crater in the square in front of the museum. A bicycle wheel appeared at the bottom of the crater, and thanks to a scholar of bicycle history, I traced the model of the wheel and its diameter, thus discovering the size of the crater, and the amount of soil that was displaced. Bringing back into the museum the soil that had exploded and making a mountain out of it is a way of filling a void. In my opinion that’s what art does: it fills in the gaps, it doesn’t give certainty or answers, that’s not its role, because works are an opaque matter, they can give suggestions, which then lead to something else.

I would like to end by reading this reflection by the famous French critic Nicolas Bourriaud that I found recently in one of his essays: “Nothing could disturb more the power than the exhibition of the ruins, the small debris and fragile images that today’s artists ingeniously extract from the archives, since it constitutes a provocation towards the defensive illusionism that proclaims the order of things as an ineluctable fatality.” How the archive, the discard, the fragile fragment according to you and according to your practice that in part has to do with these elements, can counteract the ineluctable fatality that flattens us on the univocity and the impossibility of imagining otherwise. How do you fight this fatality?

In all things there is a crack that is often invisible. Art works in that crack, forces it, because by forcing it you can see beyond the appearance. I talk about how power represents itself through something extremely concrete and glossy even. Power in all its forms, for example, even Zelensky showing up in a military sweatshirt everywhere, that too is a patina, it’s a cover, representing something. Even there you have to find a crack. Speaking of the ruins, in Don DeLillo’s White Noise he tells this story, which I can’t say whether it’s authentic or not, but the main character, the Hitler studies professor, tells about the design of Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, who had designed the new government buildings in Berlin that over the years would degrade in a romantic way turning into those images of romantic ruins, with climbing vegetation that would enclose these ruins. Here power designs its own demise and the patina it wished to assume. I don’t know whether this is fiction or truth, but I find it very interesting.