Fabbri Prize for Contemporary Arts Winners

December 2023

The twelfth edition of Francesco Fabbri Prize for Contemporary Arts, held at the Foundation of the same name in Pieve di Soligo, awarded prizes to Andrea Mauti for Emerging Art and Leonardo Magrelli for Contemporary Photography.

We met them to find out more about their artistic practices and the winning works. The sixty contenders are on show at Villa Brandolini in Solighetto until 17 December.

LEONARDO MAGRELLI

Senza Titolo (Untitled), from the series I Baccanti (The Bacchantes), is the work selected by the jury for the Contemporary Photography section. Between contemporary celebrations and archaic rituals, I Baccanti is a project in which you extrapolated images from videos uploaded online by users who filmed the celebrations for the Madonna del Soccorso in Foggia, Italy, during the lockdown in May 2020. How did you select the photos? What struck you about that story?

In May 2020, in a working-class neighbourhood of San Severo in the province of Foggia, despite the ban on public gatherings, around three hundred people took part in the celebration of the Madonna del Soccorso, an important local anniversary. Some videos of the event have appeared on social media, filmed by the participants themselves with their mobile phones, in which they can be seen chasing each other in the middle of a park, touched by the very violent explosions of the fireworks and enveloped by the luminous rain of their sparks. A dedication to a local boss killed in an ambush two years earlier also appeared on social media. No police intervention is visible in the images published.

Shortly after these events, one of these videos made the headlines and was rebroadcast on numerous news and in-depth television programmes, where there was a long debate about what had happened. That’s how I came across this video, and I was deeply touched by it.

On the one hand, some details immediately reminded me of the stylistic features of archaic Greece: groups of people praying with their hands raised to the sky, groups of men on a hunting expedition or celebrating archaic and Dionysian rituals in their unbridled vitality, in the midst of nature and surrounded by great fires that gradually become more powerful explosions, transforming the images into scenes of war. On the other hand, I think that this video highlights some contradictions that characterise our contemporaneity: we are witnessing the archaism of these indigenous religious rituals, which are struggling to adapt to our contemporary media panorama – just look at how these scenes are all recorded on smartphones, which appear in numerous images – we are witnessing the failure of state control – “an unacceptable challenge to the city and the state”, commented the mayor the day after the events – we are witnessing the latent violence of the suburbs unleashed, which breaks out and always manifests itself in different ways.

All this interested me much more than the fact that it was the time of the lockdown. For this reason, I have no desire to categorise this work as a project that is in any way related to Covid.

The lenticular printing technique you use in this series makes the image more blurred and the atmosphere depicted more suspended. Is this the feeling you were looking for?

Exactly! Lenticular printing is usually used to create postcards with a ‘before and after’ effect, where as we move the object in front of our eyes we see one image appear and then another. However, by adjusting the parallax of the grained film applied to the prints, and by working with larger formats, it is possible to achieve a sort of optical co-presence of the two images in different areas of the print. This effect is very unique because, among other things, it forces us to move in space in order to observe the constant changes that occur on the surface of the print.

In the case of I Baccanti, each work is created by sampling isolated details from pairs of successive frames. In each transition from one frame to the next, there is always a change in the lighting of the scene due to the explosions of the fireworks. In this way, cut, enlarged, grainy, fused together, devoid of any contextualisation, separated from the excitement of the flow of images and far from the noise of the fireworks, the images reveal a new aesthetic dimension and seem to evoke those new historical-anthropological connotations we spoke of earlier.

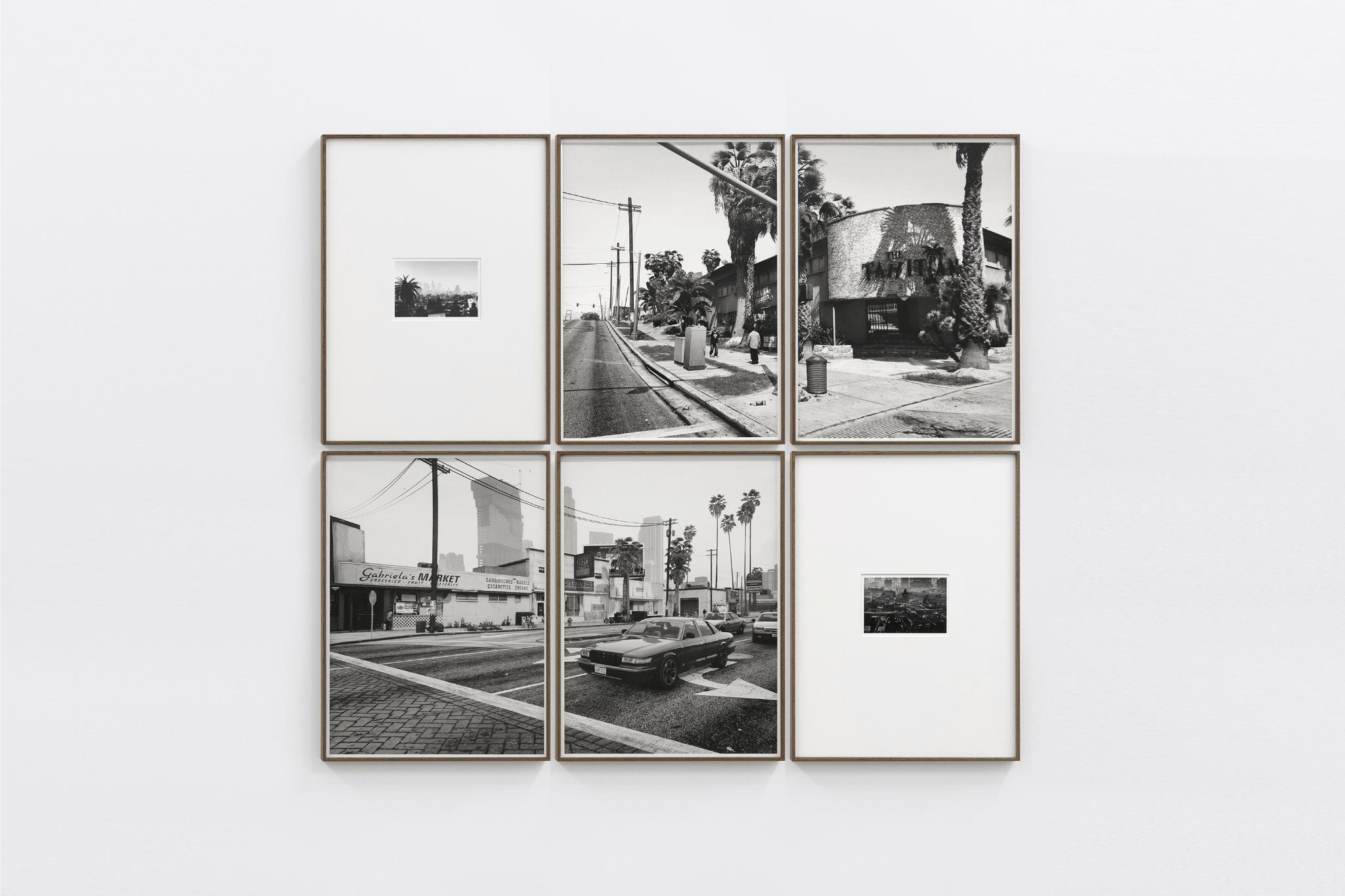

Some of your previous works play on the border between the real and the fictional, the visible and the invisible: I’m thinking of the photos of the plausible but fictional Los Angeles taken from a video game in West of Here, 2020; or the impossible portraits of mirrors in Meerror, 2016, where you show us portrait of mirrors, but the subject taking the picture is absent. Are you interested in exploring perception and subjectivity, and the ways in which they can be deceptive?

I would say that I am particularly interested in the latter, namely the way in which we fall into the trap of images. Perhaps due to my training, which led me to have a quite free and manipulative relationship with photography, I was always aware of how unstable the concept of photographic truth is, and how images can lie. I think these two assumptions have profoundly influenced my subsequent artistic practice, which has largely centred on the idea of questioning the concepts of recognition and indexicality of the photographic medium and exploring its inherent ambiguity.

When I talk about indexicality and ambiguity, I am referring to the fact that until recently a photograph, no matter how manipulated and artificial, always retained the trace of something physical that happened beyond the lens. And it was precisely the fact that there was a piece of reality in every photograph that made our relationship with the medium so complicated. Since its inception, it has become a “mirror of reality” and a paradigm of objective reproduction of the world (although many artists have intuited the problematic nature of the medium with extreme clarity from the very beginning), and it has taken us a long time to shake off this kind of blind faith and to realise that photography can be manipulated, and that it can manipulate us.

However, I think we continue to believe too much in what we see, as if we couldn’t do without. We should not underestimate this risk, especially today, when we too often see the return of propaganda instead of free information, in the coverage of wars and international crises, or when we helplessly witness how images on social media shape our expectations of the world and allow us to present a carefully crafted version of ourselves. Essentially, I find that our gullibility towards these images still stems from the presence of a piece of the real world within each photograph.

Although the relationship of photographic images to what we call reality is becoming increasingly elusive. And it ranges from the alteration of its content in post-production, to the real-time superimposition of photographic filters that modify our physical appearance, to the emulation of photographic standards within virtual realities such as those of video games, to the generation of photorealistic images by artificial intelligence, and thus to the total loss of any real referent.

We are immersed in all these changes, which are happening at a bewildering pace. No wonder, then, that it is very difficult to see it all clearly and lucidly. But art can be a way of coming to terms with it.

What are your next projects?

Fortunately, there’s no shortage of them! What is always lacking is the time to develop them. In any case, I would like to finish soon The Plant, a more strictly photographic series that I have been working on for a few years now, and in the meantime I am starting to work on a decidedly challenging project in which I would like to combine astronomical photography, sculpture, animation and installations to speak about a personal fact that has marked my life. Meanwhile, the frenetic activity with the duo of which I am a member, Vaste Programme, continues. Fortunately, we still have a lot of ideas we can’t wait to pursue.

ANDREA MAUTI

Untitled is the bronze sculpture that won the Emerging Art section. It is a small abstract sculpture that simulates an artefact from distant times and places. The recycling symbol emerges from the undulating surface as the only truly legible element. How do you decide, if you decide, the forms of the works? How do you choose or create these forms? I am particularly interested in the gap between the paintings, which are figurative, and the sculptures, which are purely abstract.

I am interested in exploring a physical contingency of the material and objects I work with, as if the traces left on things were testimony to a suspended time, at the same time archaic and futuristic. In this way, the forms and industrial hybrids that emerge during the process are born and transformed autonomously, as if we were confronted with active, fluid presences that react with each other in unexpected ways, without my exercising direct control over the realisation of the artefacts. The result of this process could be compared to the impossibility of placing objects, which become part of a global and unidentifiable ecosystem, in a specific context.

Very often I decide to leave symbols, as in the sculpture Untitled, or imperceptible linguistic traces that refer to a conventional language used within the so-called supply chains, capable of determining the specificity of a product, of an object, sometimes of animals, in order to classify, categorise and fix them within pre-established identifying categories.

The codes that remain imprinted on the sculptures are completely transfigured by the reactions that occur between the different materials, losing their semantic value, which does nothing but limit our experience of the other.

Very often, as in the current exhibition at ADA, the sculptures take the form of pelvis, creating full and empty spaces, welcoming and rejecting the viewer within the space. The images I had in mind when thinking about the installation architecture to be reconstructed in the gallery were archival photographs of hermaphroditic animal pelvises found in the Queer Archive in Munich when I was making the work I submitted for the award. The small bronze was originally a polystyrene frame protecting a small screen. These cracks in the industrial packaging are portals to other realities, as if they were invisible screens on an iPhone.

Sometimes the sculptural forms take on the appearance of unidentifiable creatures bordering on the monstrous. For me, they become mythological bodies or artefacts, reminiscent of archaeological imagery, created from our own daily waste, from our actions on earth. A possible alchemical reaction between disordered and overlapping spatial and temporal realities.

In painting, this temporal gap is much more visible and carries with it an anti-monumental idea of classical heritage, reinforced by gestures, fragmented and time-scarred bodies that inhabit the canvases as if they were everyday scenes, while digital veils of polystyrene are imprinted on the canvas as if to contain the sculpture and create a temporal gap between different archaeologies.

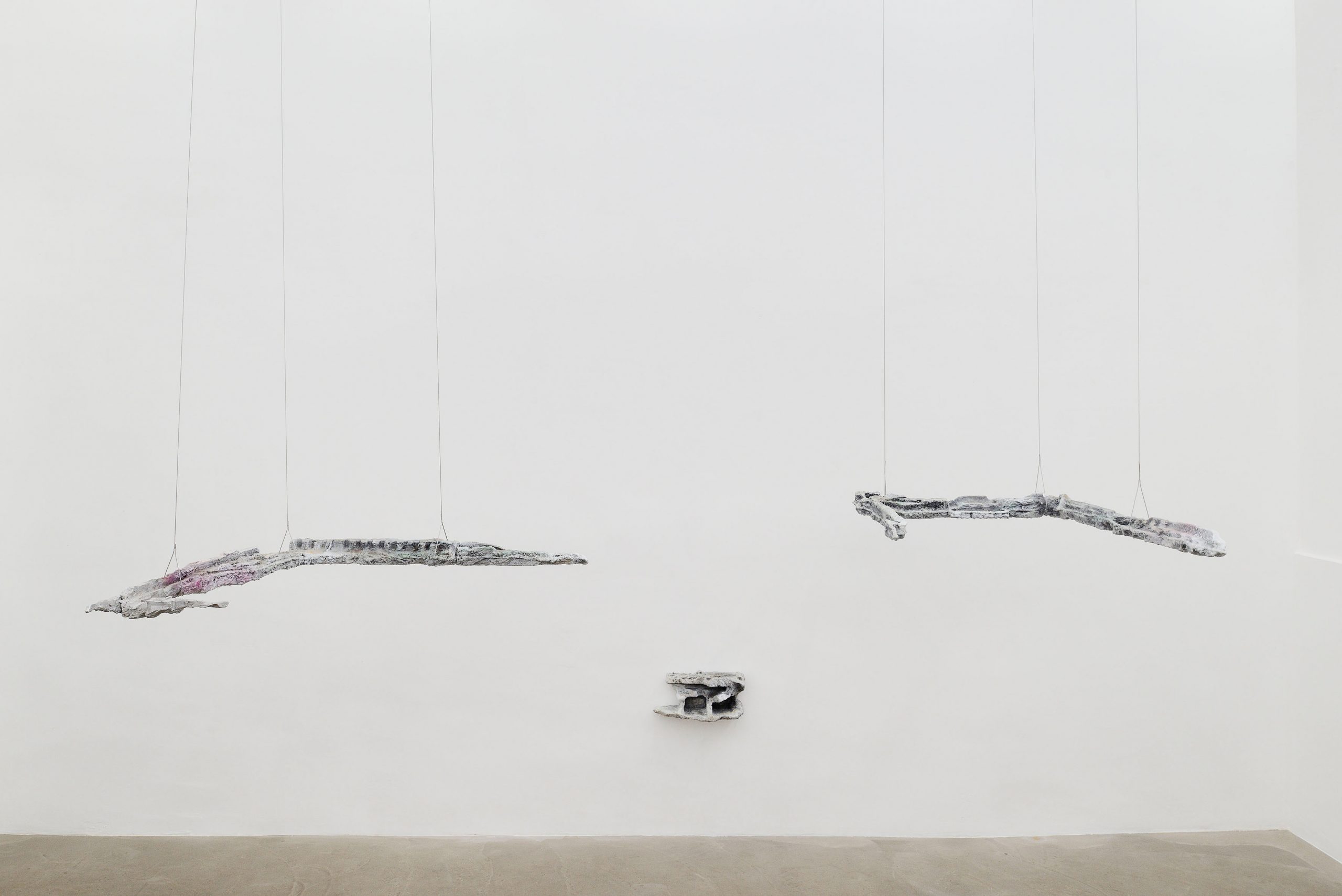

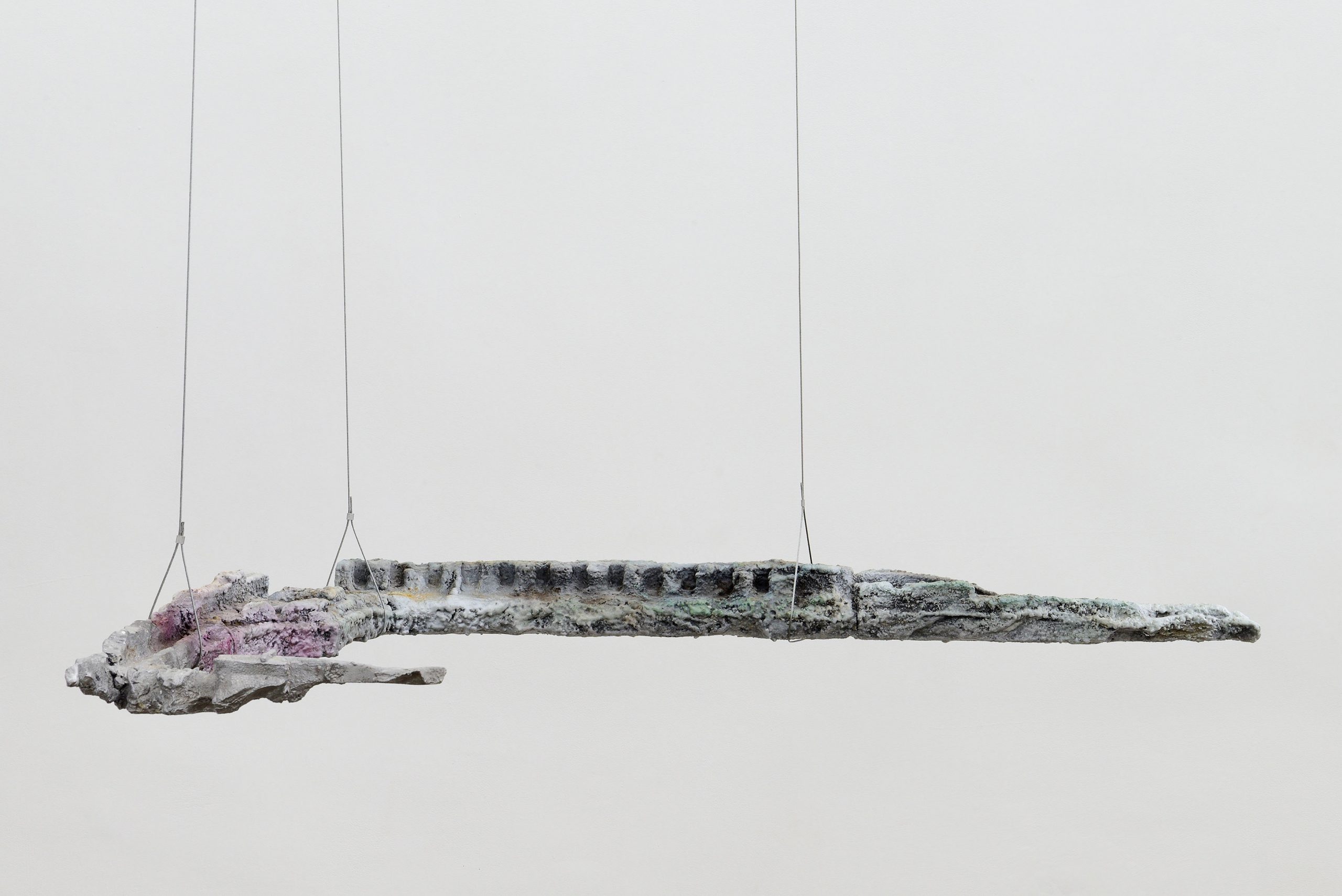

You are currently having a solo exhibition at ADA Project in Rome titled Ænd. There you present a series of resin, aluminium and silicon sculptures that float in mid-air. Your work has been defined as a kind of ‘fantarcheology’, a discipline that overlays the study of antiquity with science fiction and post-human, even post-apocalyptic scenarios. What does the title refer to? What interests you about the chronological disorientation that seems to characterise your modus operandi?

The title of the exhibition is the crasis of the term “end”, as the end of a narrative, and “and”, as a conjunction that announces a time that tends to run out and self-destruct, in the possibility of a future outcome of the current social and political reality. ÆND is the result of an interest in the study of apocalyptic theories and thoughts, as in the case of Ernesto de Martino, which express a strong tension between the future and the present, which seems increasingly dark and irreversible.

What we are witnessing more and more frequently is a strong precariousness of the human condition, ecological disasters, the emergence of ever stronger nostalgic political regurgitations. All these factors create a sense of alienation and unhappiness very similar to that evoked and staged by science fiction, where the fiction given by the simulation of parallel scenarios actually surpasses, if not prophetically anticipates, phenomena that undermine the presence of humans, other species and the ecosystem in which we all live.

In this sense, the Covid experience was a historical moment in which time was irreversibly catalysed, a constructed time, and we found ourselves immersed in a possible scenario akin to a Cronenberg film or Gibson’s Neuromancer.

As Bifo wrote, we were faced with an invisible creature that undermined our centrality in space. Intubated and helpless people, decomposed bodies, deserted streets… However, this phenomenon has done nothing other than to consolidate a disruptive accelerationism in which reality seems to be even more anxious, possessed by a dark and obsessive will that agitates our lives and generates strong psychological and, above all, physical traumas.

As a result, there is no longer a linear time dimension: the past tends inexorably to present itself to us anew, accelerating and constantly withdrawing into itself.

“There are things down there that are not made for the eyes of men, but for those of souls,” says one of the characters in La Chimera, Alice Rohrwacher’s recent film about a group of grave robbers. I quote it to you because it struck me while I was watching the film, and it resurfaced when I was thinking about this archaeological approach that pervades your work. Is there also in your work a tension to reconstruct an aura for these objects?

And while Italia, played by Carol Duarte, says that line in the scene you mentioned, the landscape in which the characters are immersed is the Tarquinia coast, at night, while the monstrous Civitavecchia power station acts as a backdrop, emitting light signals that reverberate on the site where the sculpture was found.

It is this archaeological tension that interests me in the film and that I find in my work. A superimposition of contaminated landscapes, where the present, the archaic and the future overlap in a single cinematic frame. The moment when the head is found, and literally cut out of the sculptural body, seems to unleash a dark spell that then reverberates in the gestures and actions of the protagonists.

The sculptures present in La Chimera, like mine, are absorbed by a dark spectre, they live in the shadow of the cultural substratum. They are bound to darkness by a mysterious magic, and at the same time they become a concrete testimony to what is stirring above: in the specific case of the film, the Civitavecchia thermoelectric power plant, with its impact on the landscape and the environment.

This telluric instability echoes in the sculptures, which by this means they become a subterranean and organic testimony to our present. They are hyperobjective and toxic slags that emerge from the scaffolding of capitalist society, a possible fragmentation of a contaminated landscape in which identity is suspended in objective, digital and fluid representation. In ADA’s current exhibition, these suspended bodies become shifting organic presences, staging a danse macabre in which the body extends beyond carnal walls, between wires and electrical pipes, between architectural scaffolding, between virtual realities, to create multiple identities.

Recovering found objects, toxic and digital waste, bodies and organic materials, like an archaeologist I try to reconstruct a dystopian and unreal image of time.

Unravelling the world, breaking down the scaffolding that supports the contemporary systematic system and plunging us all together into the mud of a damaged planet.

You are currently in residence at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris, what are you working on?

During this residency, I travel frequently between the outer and inner spaces of the city of Paris, mapping a kind of cartography of objects found in specific areas of the city, between the suburbs, where gentrification is greatly altering the urban fabric, and the city centre, where strong political tensions reverberate.

My research project moves between archival images from 1860, during the experience of the Paris Commune, and how protesters literally subverted urban space by creating Protest Landspaces, to the experience of Guy Debord’s Derive, whose writings and drawings, as well as sculptural models, lead me to rethink our way of living and moving in the arteries of cities. Through the retrieval of documentary photographs on the antimonumentality of architecture and the making of a video that will be part of a project that I intend to develop over a long period of time, my work at this stage is nourished by historical and political references that help me to construct an archaeological imaginary that absorbs the toxic waste of our society. In parallel, I am beginning to write and collect textual fragments that will help me develop a performative project in which the presence of the performers’ bodies acts as a catalyst for external inputs and uncontrolled gestures within a contaminated and organic playground.

PHOTO CREDITS

Leonardo Magrelli detail of Senza titolo, from the series I Baccanti, 2023, UV print on lenticular lens, diptych. Courtesy of the artist and DIVARIO, Roma

Leonardo Magrelli, Senza titolo, from the series I Baccanti, 2023, UV print on lenticular lens, diptych. Courtesy of the artist and DIVARIO, Roma

Leonardo Magrelli, Follia Sacra, Installation View, DIVARIO, Roma, 2023. Photo © Studio Daido

Leonardo Magrelli, West of Here, Installation View, Talent Prize, Museo delle Mura, Rome, 2022

Leonardo Magrelli, Cold Canyon Rd, Calabasas, Los Angeles County, California, from the series West of Here, 2020-2021

Leonardo Magrelli, #58, from the series Meerror, 2016

Leonardo Magrelli, #59, from the series Meerror, 2016

Andrea Mauti, Untitled, 2022, bronze, oxidesi. Courtesy ADA, Rome

Andrea Mauti, “ÆND”. Installation views at ADA, Rome, 2023. Photo credit: Roberto Apa. Courtesy of ADA, Rome.

Andrea Mauti, Hybrid Enclosure, 2023, resin, paraffin, aluminium, textile fibres, silicone, pigments, organic elements. Photo credit: Roberto Apa. Courtesy of ADA, Rome.

Andrea Mauti, Memory of a Floating Time Body.Ext, 2023, resin, paraffin, aluminium, textile fibres, silicone, pigments, organic elements. Photo credit: Roberto Apa. Courtesy of ADA, Rome.

LEONARDO MAGRELLI

Leonardo Magrelli (1989) lives and works in Rome. After studying Design first and Art History later, he began working as a graphic and book designer. A certain openness to manipulation and reuse of images, inherent in the graphic design work, as well as a particular attention to project and research, rather than instinctuality alone, are characteristics that remain visible in the author's practice even after converting to photography. The awareness of images’ hybrid and ambiguous nature is in fact a constant subtext of his work, which varies from time to time between a more conceptual approach to photography and a more descriptive and documentary one, often mixing the two. Alongside his personal research, he collaborates with the collective Vaste Programme, founded with Giulia Vigna and Alessandro Tini in 2017, to experiment with post-photography, installations and new media.

ANDREA MAUTI

Andrea Mauti (Rome, 1999), lives and works in Marino, Rome. He graduated at the Accademia di Belle Arti, Rome, in 2022. Recent and upcoming exhibitions include: 2023 – ÆND, ADA, Rome; Big Bang, CURA. Basement, Rome; Baraondah, curated by Gianni Politi, W, Rome. 2022 – Collettiva #2 Monitor, Pereto, Rome, Lisbon; Scoppio Terzo, Terni; sublimation_simulation, ADA, Rome. 2021 – Masters Salon’s paintings, in collaboration with European Academies of Fine Arts; Hétérotopie, curated by Edoardo Monti Bubble’n’Squeak, Bruxelles. 2020 – Degree Show, Palazzo Monti, Brescia; INSIEME, curated by Gianni Politi, group exhibition powered by MACRO, Via di Porta Labicana, Rome; Back to Nature, curated by Costantino d’Orazio Villa Borghese, Rome. Residency projects include: Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, Nuovo Grand Tour, Ministero della Cultura(2023/24); Akademie der Bildenden Künste, München (2021).

LEONARDO MAGRELLI

Leonardo Magrelli (1989) lives and works in Rome. After studying Design first and Art History later, he began working as a graphic and book designer. A certain openness to manipulation and reuse of images, inherent in the graphic design work, as well as a particular attention to project and research, rather than instinctuality alone, are characteristics that remain visible in the author's practice even after converting to photography. The awareness of images’ hybrid and ambiguous nature is in fact a constant subtext of his work, which varies from time to time between a more conceptual approach to photography and a more descriptive and documentary one, often mixing the two. Alongside his personal research, he collaborates with the collective Vaste Programme, founded with Giulia Vigna and Alessandro Tini in 2017, to experiment with post-photography, installations and new media.

ANDREA MAUTI

Andrea Mauti (Rome, 1999), lives and works in Marino, Rome. He graduated at the Accademia di Belle Arti, Rome, in 2022. Recent and upcoming exhibitions include: 2023 – ÆND, ADA, Rome; Big Bang, CURA. Basement, Rome; Baraondah, curated by Gianni Politi, W, Rome. 2022 – Collettiva #2 Monitor, Pereto, Rome, Lisbon; Scoppio Terzo, Terni; sublimation_simulation, ADA, Rome. 2021 – Masters Salon’s paintings, in collaboration with European Academies of Fine Arts; Hétérotopie, curated by Edoardo Monti Bubble’n’Squeak, Bruxelles. 2020 – Degree Show, Palazzo Monti, Brescia; INSIEME, curated by Gianni Politi, group exhibition powered by MACRO, Via di Porta Labicana, Rome; Back to Nature, curated by Costantino d’Orazio Villa Borghese, Rome. Residency projects include: Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, Nuovo Grand Tour, Ministero della Cultura(2023/24); Akademie der Bildenden Künste, München (2021).