Your painting style already seems extremely mature. It is characterised by an intimate language which accumulates elements and impressions like notes from a screenplay that is eventually enacted following the rhythms of the layers of colour and paint on the canvas. In fact, your approach seems linked to your educational path (set design) and the attention towards symbolic and expressive details that is typical of fashion and theatre. How did you come to have such a specific language as an artist? Has it developed by itself or have you trained it? And do you think there is something innate in your personal inclination and creative sensitivity?

The achievement of a personal language must come from a path that starts from various contaminations. In my case, having touched various worlds, from set design to fashion to children’s illustration, I’ve always hoped and aimed to unite all these aspects. For example, I originally studied set design, and due to this, I like to think of myself as the “prop master” for my compositions. These experiences led to the discovery of an involuntary, though manageable, synthesis, and therefore to a language that is more or less mature. As far as I’m concerned, my painting practice has changed drastically in the last few years. Previously, it was still very immature: it still had deviations and a need that was linked to the idea of figuration as an end in itself.

To this day I can say that I have actually come to be a figurative painter while starting from a path of abstraction: only by stepping away from the canvas and reading it from a certain distance was I unexpectedly able to understand that figuration was actually the result of an abstract process, of a sort of mapping and union of chromatic levels, matter, removals and transparencies. That was something that could happen in Berlin, where I had the opportunity to work in a very large studio. In the space that formed between the canvas I was painting and the positioning I chose for reading the work – that’s where I found painting. It became something almost performative: that moment in which I put down the brush and stepped back was something totally new, which has now become fundamental in my painting practice. I still don’t know whether in a few years I’ll reach an even more abstract idea.

One of your most recent collaborations, right before the pandemic I think, was your residency in Los Angeles, which opened the possibility for new opportunities in the United States, the latest being the group show at Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York. How has the American experience influenced your artistic language, aside from the future possibilities for your career?

As a European, having had the opportunity to work overseas, you always bring your cultural baggage with you, which inevitably presents itself when you face other cultures, such as the U.S. It definitely helped me to get out of my comfort zone, but mostly I enjoyed finding myself in the atmosphere of one of my favorite movies, No Country for Old Men (2007, written and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen). In this movie you feel the sense of unease and claustrophobia of a series of abandoned motels between California and New Mexico: more or less the same sensation you can sometimes find in my works. It’s not a coincidence that one of my latest works is called Sweet Baby Motel. This experience certainly allowed me to add some elements, even with respect to the preconceptions I had, and combine them with other elements that I had left unfinished. For example, before I left America I wanted to create a series, because working in series helps me with the idea of narration. From Los Angeles to the desert, the Americana series of paintings was born. All that glitter and the fluorescent colours around the city are actually very distant from the melancholia that permeates my works, which belongs much more to European and Nordic tradition. This exact contamination created a strange yet powerful mix of elements that actually showed up in the works I made once I returned to Europe.

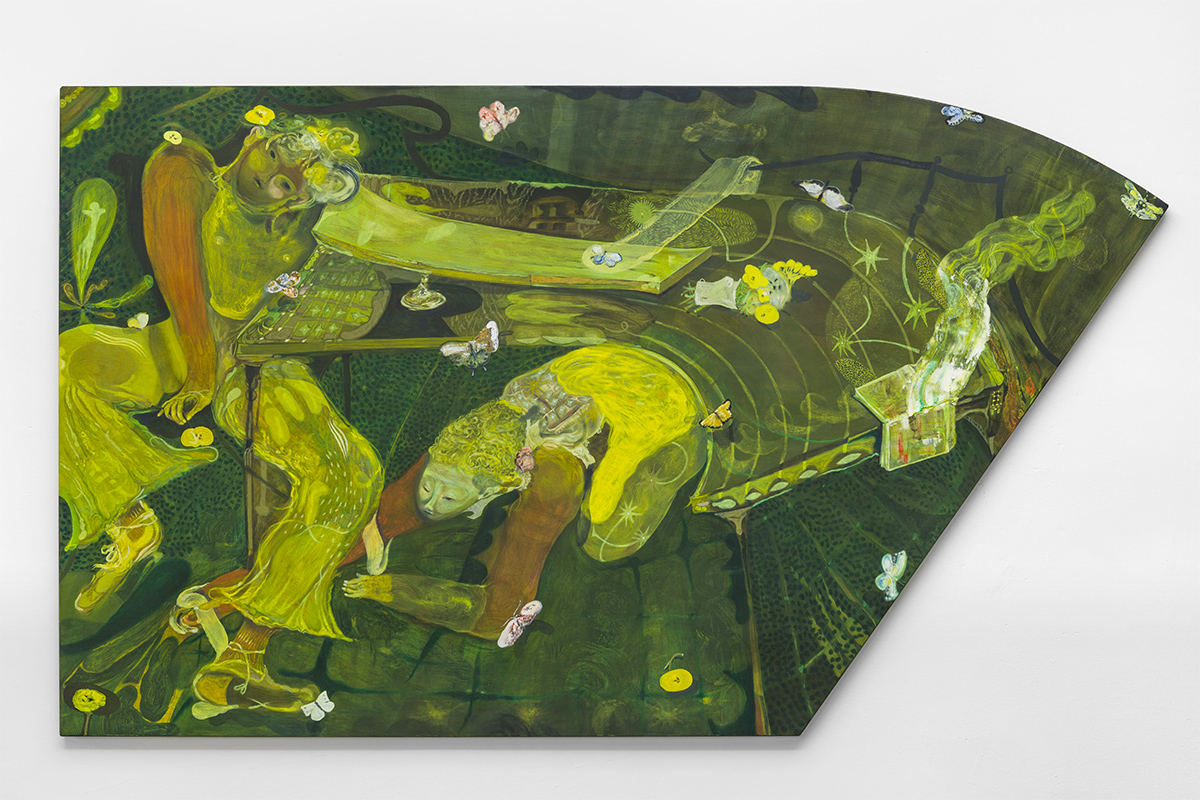

OPERE DELL' ARTISTA

This kind of figurative painting, with its bright and lively tones, originates from the United States and is very popular nowadays. Your artistic practice shares this tendency both on the formal side but also with regards to colours and subjects. And yet one also senses a very particular emotional and expressive depth. Perhaps, as you said, it is a truly European influence. The contours of your figures often burst as a result of external, and especially internal, movements. In this sense, your figuration refuses to be entirely explicit, presenting a “dramatic” depth in your staging of universal human emotions. How do you think your language differs from that of your American contemporaries?

I didn’t study painting – I come from drawing and theatre – it just came to me out of necessity. I could never separate things or deny my varied cultural background and the stories and suggestions that come with it. It’s true that figurative painting is very popular today. I’ve always done it, on different levels. But I’m not interested in the genre, for example. Perhaps my figuration also works because, paradoxically, it comes from a place of abstraction. Mine is a narration understood in terms of time and space, and therefore it has a universality of subjects and stories – its own space where something can happen. The fact that it is impossible to trace its origins, and that it has multiple layers, both technically and in terms of its reading, means that my painting practice is explicitly bound to other media, for example ballet or performance. These representations, these scenes, belong more to a European method than a foreign one.

Almost all of your works seem to be touched by a certain langueur, a trace of melancholy. In your interviews, you often describe a state of nostalgia. However, it is a type of nostalgia that is closer to that which might develop during a moment of cultural shift, such as during the Romantic or Decadent movements, with their longing for the classics or for ruins, for the past and lost perfection. What kind of nostalgia does your work speak of? Is it more linked to an external or inner world? And how does it relate to our present – or is it a way to react and escape from it?

I think my paintings are somehow outside of time. It is a nostalgia that sometimes sounds discordant, but in a voluntary and conscious way. For this reason, chromatic elements such as acid colours and structural dysmorphism take over. In any case, it is a nostalgia that perfectly fits a historical moment like ours, in which a speed is required that painting cannot have. It is a nostalgia that speaks of a difficulty in relating to one other. My painting is a kind of matryoshka, where there is space, the body, and then the body with the space again. They often trespass upon one another, and one is maybe too big or too small for the other, rejecting a real dialogue between them. They are basically imbued with melinconia, which is the step before malanconia; it is not yet a pathological state, but can affect anyone and is affecting a lot of people at the moment. Paradoxically, during the pandemic we have realised there can also be positive sides to this feeling, such as creating an essential moment of reflection within ourselves.

It is also a nostalgia with respect to the care of things, and of ourselves, which is no longer practiced. I cannot state that it was better before – I wonder, before what or who? And before when? But I think to sidestep things is a way to observe them differently, not necessarily in a deeper way, but with more feeling and attention. To quote Marguerite Yourcenar, Two Lives and a Dream, 1982: “How strange each existence is, where everything floats past like an ever-flowing stream and only things which matter, instead of sinking to the depths, rise to the surface and finally reach, together with us, the sea.”