Born in Germany, Iris Buchholz Chocolate lives and works a Luanda. She investigates notions of perception and memory, at the crossroads between the canon of history and the collective memory archive. She works with local artisans to develop a poetic narrative that brings together different time frames and questions how they interfere and become part of the collective and individual memory.

You have been living in Luanda for more than a decade, and maybe it has occurred to you that more than once people may have thought that you are Angolan. Can you tell us of how you came to have this symbiosis with the Angolan art and culture?

After university, I was backpacking in South Africa and met by chance the Angolan artist Fernando Alvim, who invited me shortly after to join Camouflage Brussels with its 300 m2 exhibition space, Coartnews publications, Autopsia archive and Área residency program; it was one of the first art spaces across Europe promoting contemporary art from Africa. My plan was always to do a master’s in art, and as it turned out all these years in Brussels surrounded by African intellectuals and artists, running one of the biggest collections of contemporary African art at the time, was the best MA program I could have wished for. I wrote my final thesis at the university on the space of political will and in Brussels I found a group of Africans trying to make themselves heard in the international art scene, so I joined their cause. Remember that in the early 2000s, for many European curators contemporary African art did not even exist. In the meantime, most of these artists and curators, who were at the beginning of their careers when they exhibited with us, have become well established in the international art scene today, for example Otobong Nkanga or Elvira Dyangani Ose. Fortunately, 20 years later no one questions the existence of a thriving art scene in Africa and its diaspora. In the European educational system, you don’t necessarily learn to look at yourself through the eyes of other, or what imperialism did and is still doing to the involved societies. This is something that hit me when I started working in Angola in 2003 as part of the team that set up the first Trienal de Luanda, which produced the first generation of internationally successful Angolan artists, such as Kiluanji Kia Henda, Nástio Mosquito or Edson Chagas. Now it’s already the turn of the youngest generation, with Helena Uambembe or Sandra Poulson. It feels good to have been part of the process. I guess somewhere along the way I became Angolan too, as I’ve been arguing all these years for the same cause. This is the community I live in, I reflect on, I teach, I share troubles and collaborate with. Angolan sponsors make my projects possible. The first collections I sold my works to are Angolan. More than once, I heard the compliment “You are one of us”, but of course I recognise that my gaze comes from the outside too. Right from the beginning, it has been my conscious choice to stick with my German surname in the middle, and through my work I try to understand the culture that formed me, as well as the culture I live in now.

The last two years have been challenging for all, not only in terms of health and our way of living, but also in terms of professional perspectives. How did this period impact your art?

Ancient Egyptians believed that the first and most important element in the universe was chaos. It could wipe you away, but it is also the place from which all things start anew. Here, in Angola, you very often react to situations that are not foreseeable. By default, Angolan citizens are professionals at being resilient, as crises are omnipresent and manifold: the aftermath of oppression and war, neglected infrastructures, health, education and administrative services enter their lives in the form of traumas, anxiety, missing electricity or water, moon-like craters on the roads, frequent funerals, malaria or yellow fever outbreaks or Kafkaesque situations while doing paperwork. And then there’s inflation and the devastating decisions of the IMF affecting the country’s economy. Here, the pandemic is just another one of the many problems that society faces anyway. Only few have the luxury to work from home, so life continues – with restrictions of course – but is pretty much the same as always. A hard lockdown is not possible in a country were many live from what they earn every day. Luckily, 65% of the population is under 25, and that might be an advantage, although I am pretty sure that mortality rates are much higher across the continent, but what you don’t count doesn’t show up in any statistics. As far as my work is concerned, since the 17th Biennale of Architecture in Venice was postponed to 2021, we had much more time in 2020 to prepare our work Unfolding Urban Ambiguities – Prédio do Livro. The challenge was to come up with a huge size with as little weight and transport volume as possible. After numerous tests, I found a solution: for the upper part of the installation, I developed a poetic installation called Emotions raining inside people’s bodies, flowing down into dreams, made out of 8,665 ribbon markers that refer to the (hi)stories and memories of the Prédio do Livro. The idea stemmed from me thinking about all the people who have lived, loved and maybe died in this modernist building in the shape of a book, since colonial time until today. As you mark a page in a book with a ribbon marker, each ribbon symbolizes a moment in life. The only thing we can rely on is the fact that “all things are momentary and pass away”. Scientists have developed a profound understanding of the patterns of change and stability in the universe. From one day to the next, the water molecules flowing in a river are entirely different, yet the river may look exactly the same for millennia. Neo-Confucianism philosophers recognized that all the patterns in the universe ultimately affect each other, just like multiple ripples on a lake intersect and create new patterns. Likewise, the ribbons create ripples and patterns, they move and interact like a living organism as the wind passes through them. Movements, small or large, invite the observer to meditate and dream. In the end, due to lack of funding, only the lower part of the project – a light table including a model – was exhibited in Venice. The missing upper part the installation was luckily exhibited during the Bienal de Luanda: Fórum Pan-Africano para a Cultura de Paz, in November 2021. This means that, through time and space, in two Biennales on two continents, the initial idea did come to life.

In your projects, you often refer to local culture as the substrate that shapes cultural identities. How do you perceive the role of localness in a fast-changing world where globality seems to have swallowed many of the features that, a few decades ago, made a lot of difference between peoples and cultures?

I do think it is crucial to preserve different cultural identities, to stop the still dominant worldview of consumerism from merging everything globally beyond recognition, exploiting what is left of our mother earth. When, in my art, I started to reflect on Angolan (hi)stories, local crafts seemed to be the tool to understand many things. Indigenous worldviews around the world contain the much needed wisdom to change our behaviour towards nature, and the more our lives drift unstoppably towards the digital, the more I seem to honour the ancient knowledge of crafts. Maybe you know that the Portuguese introduced Assimilation Politics in their colonies, meaning that the only black people who were allowed to walk on asphalt or access education had to talk, dress and behave as a Portuguese. Whenever they spoke their mother tongue, they risked losing their assimilation passport. In a way Apartheid, which was likewise brutal, seemed to be more honest, in the sense that it declared the other as inferior. However, communities continued to exist with their ancestral legacy, their oral culture, rituals, music and so forth. Obviously, it is the so-called assimilated elite from those times that is running the country now. It is nobody’s fault: it is what history left behind. But in order to heal this devastating painful past, it is crucial to understand why people behave as they do. Naturally, most of the population speaks Portuguese as a second language, as the educational system is what it is, it is difficult to learn proper Portuguese in school, even more so if you don’t hear it at home, with the result that Angolans who speak fluent Portuguese often look down on their fellow citizens as less worthy. Likewise, there is a push and pull movement between being proud of the tradition, the local identity (including craft artists), and looking down on it as somewhat backwards. This is the drama, the wound that I intend to mirror back to society. The silence in between generations, which I know too well from my own family’s story, appear to be deafening. Well, it is nothing less than painful to ask your parents and grandparents about the time when colonial rule was applied, or to look deeper into your ancestral lineage. A student of mine once told me how difficult it was for her, during a visit to Nigeria, to admit that the only language she speaks is Portuguese, as is her name. So, she named her daughter after an Angolan queen. Our name “Chocolate” is obviously a leftover from colonial times; the sad thing is nobody in the family remembers the family’s original name. Erasing your culture starts with erasing your name, which is a crucial part of your identity. On the other hand, this name reflects the country’s history. Anyone who wonders about the name “Chocolate” is already reflecting on colonialism. As it happened in Brazil, after liberation former slaves took the name of the plantation owners they worked for. The rise in extreme inequalities is tearing Angolan society apart. Which leads to the recognition that true wellbeing can only exist within a flourishing community embedded in a healthy society and a thriving natural world. Art allows me to reflect on human geographies, to produce work based on my memories, to describe pain, safeguard experiences from oblivion, as well as to imagine the future by investigating craft and natural materials. I reflect on conscious realities, communication and forms of community – as only in the mirror of the life of others can we understand our own lives. Only in the eyes of others can we become ourselves.

What is next in your art?

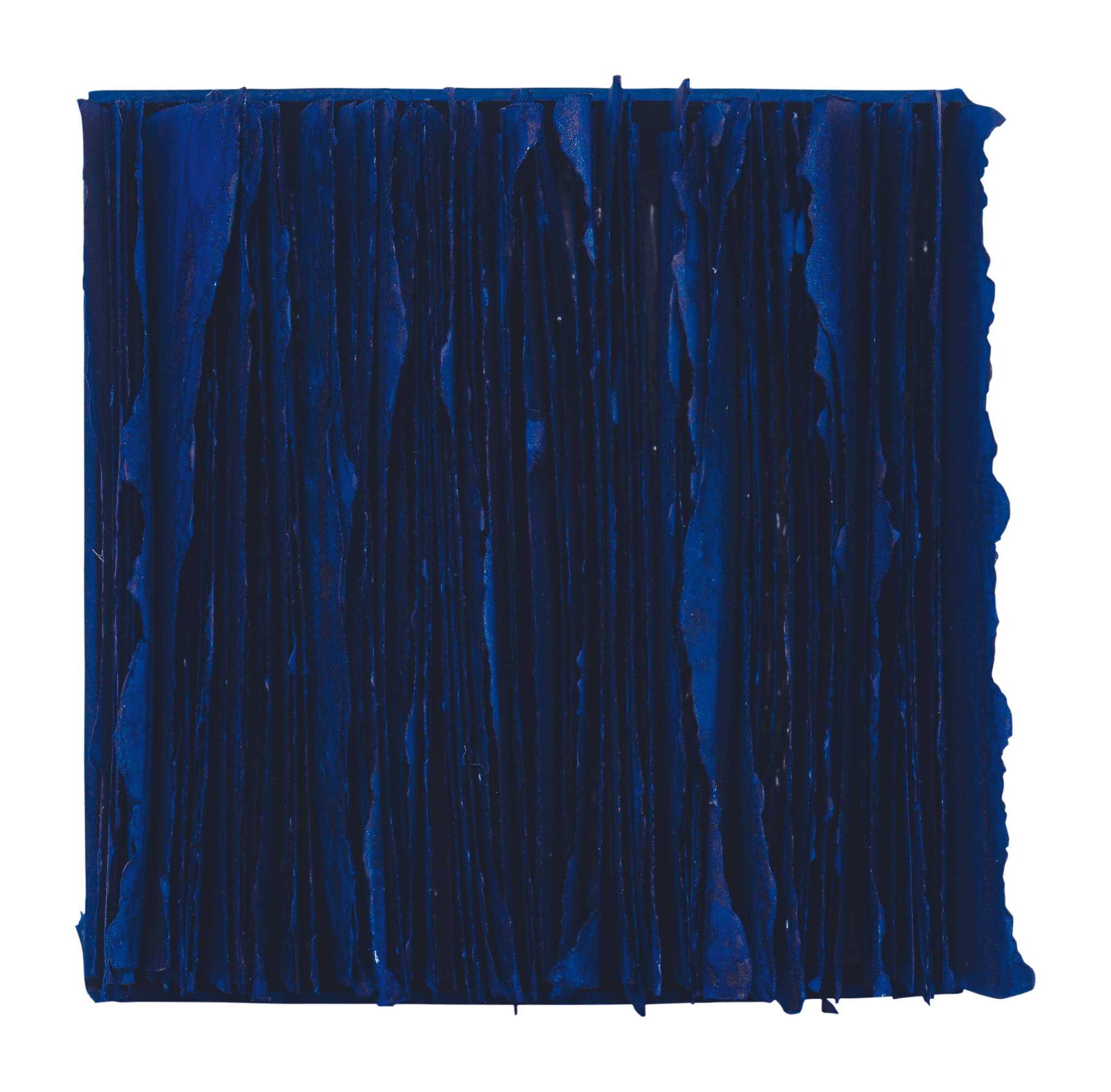

My work is research based and quite often includes a long period of investigation. Right now, I am focusing specifically on a major exhibition project: What is the colour of the wind? It introduces the concept of Lugânzi – The Living Archive, a research platform for education, art and culture. The show will exhibit artworks from the series mobile realities, and the series “conscious colours”, which investigate forms of togetherness and the use of urban, rural and ancestral colours. This stems from my earlier exhibitions in Luanda and my collaborations with Angolan curator Tila Likunzi. We invested a lot of time in creating educational programs for the shows. The impact of these programs was tremendous. We introduced something new into local shows – explanations of certain cultural, philosophical or historical aspects behind the art – which made many of our audiences aware that something crucial was lacking in their education: the access to knowledge about their own cultural and historical roots. This is when the entire idea of Lugânzi [meaning roots in the African language iwoyo] took shape: a free digital archive, a research and publishing platform focused on exploring, producing and sharing knowledge on ancestral and contemporary Angolan and African arts, languages, philosophies, beliefs and customs. After some years of preparation, we have now finalized the website. The concept will be presented with the exhibition, which will share our pilot project, both physically and online, and hopefully we will find partners and like-minded people to kick off a larger program next year. One of my favorite Lugânzi quotes is: “the process of decolonizing thinking and unlearning the complexes of colonial and modern legacies is challenging, but knowing one’s roots is the first step to live conscious realities that can generate truly independent works and beings”. I am very happy that, through this project, I can be of service to the Angolan society and share the vast knowledge I have learned, and will continue to acquire, in my professional life.

PHOTO CREDITS

A Metamorfose Sculpture: Mixed media, metal, handcrafted panels braided out of dry plants, 600 x 250 x 250 cm, 2010 Conceived for II Trienal de Luanda.

Photo credits: Claudio Chocolate

Okufeti(ka) – Exhibition view Iris Buchholz Chocolate, Jahmek Contemporary, Luanda, 2019

Photo credits: Claudio Chocolate

A Sul. O Sombreiro — luvas com missangas Sculpture: Metal gountlets, fabric, braided artificial hair, feathers, 2015

Photo credits: Claudio Chocolate

Emotions Raining Inside People’s Bodies, Flowing Down into Dreams, conceived for the Venice Architecture Biennale, exhibited at Bienal de Luanda Installation: metal frame, PVC boards, 8.665 ribbons, 522 x 400 x 79 cm, 2021

Photo credits: Claudio Chocolate

Starbook, 2019 Drawing: Print on gauze, 2x (3x) 140 x 100 cm, brass supports

Photo credits: Claudio Chocolate