Features #12 — October 2022

Jeremy Shaw in conversation with Nicolas Vamvouklis

The first idea that comes to mind when I think of your work is transcendence. Was there any specific event in your life that led your research in this direction?

I grew up Catholic, so from a very young age, I was learning about transcendental spiritual experiences. But they were either something you had to earn through committed diligence, piety, and ritual or something you were gifted as a “chosen one.” So, although I was very aware and enamoured with the idea of communing directly with God, it sadly never happened to me. I took LSD for the first time at 14, which would definitely be the first vivid personal experience I can recall that led me in this direction. Even though it was much before I started making art related to these experiences — except for trying to draw the patterns that I saw covering every surface that night — that moment reopened my sense of wonder with the world and has remained with me to this day.

When trying to reach for something ‘beyond,’ it is impossible to predict or even describe what this experience will bring. I acknowledge this spiritual process can be therapeutic, but at the same time, the fear of the unknown is present. What drives you on this journey?

For me, it was having such a mind-blowing experience, like I just mentioned, quite young, and then continuing to try and recapture that moment for years afterwards. It’s generally a fraught quest to try and reach that climax again, as I believe you can truly only have your mind blown a handful of times. But that doesn’t stop you from searching and from learning many incredible things and limits along the way. So, in taking acid that first time, in learning about the burning bush at catechism, in visiting ashrams, in meditating and doing yoga and dancing for hours and hours and hours, I’ve seen glimpses that there is more to our reality than this present, perceived moment we’re functioning in — and that’s simply what drove me to keep trying to see even more of it. I’m certainly not pursuing the chemical arena of that quest these days, but I’m still totally fascinated by those that continue to push into these unknown realms — as well as by the scientific community that is working to empirically map what is happening in the brain during these experiences.

Five years ago, you posted on your Instagram account a still from the video work “Quickeners” (2014) with the subtitle “I feel the need to believe.” How do you relate to this line today?

Oh, I still feel the need to believe. Maybe even more so these days.

What do you think makes an artwork political? Would you say that the post-documentary spaces you create have such an extent?

I think contemporary art is inherently political. In co-opting the aesthetics of documentary cinema — something that’s recognised for its veracity, its apparent truth or transparency as a medium — I am creating works that manipulate our relationship to history and media and, oftentimes with that, the politics of yesterday, today and tomorrow. So yes, I think they’re political.

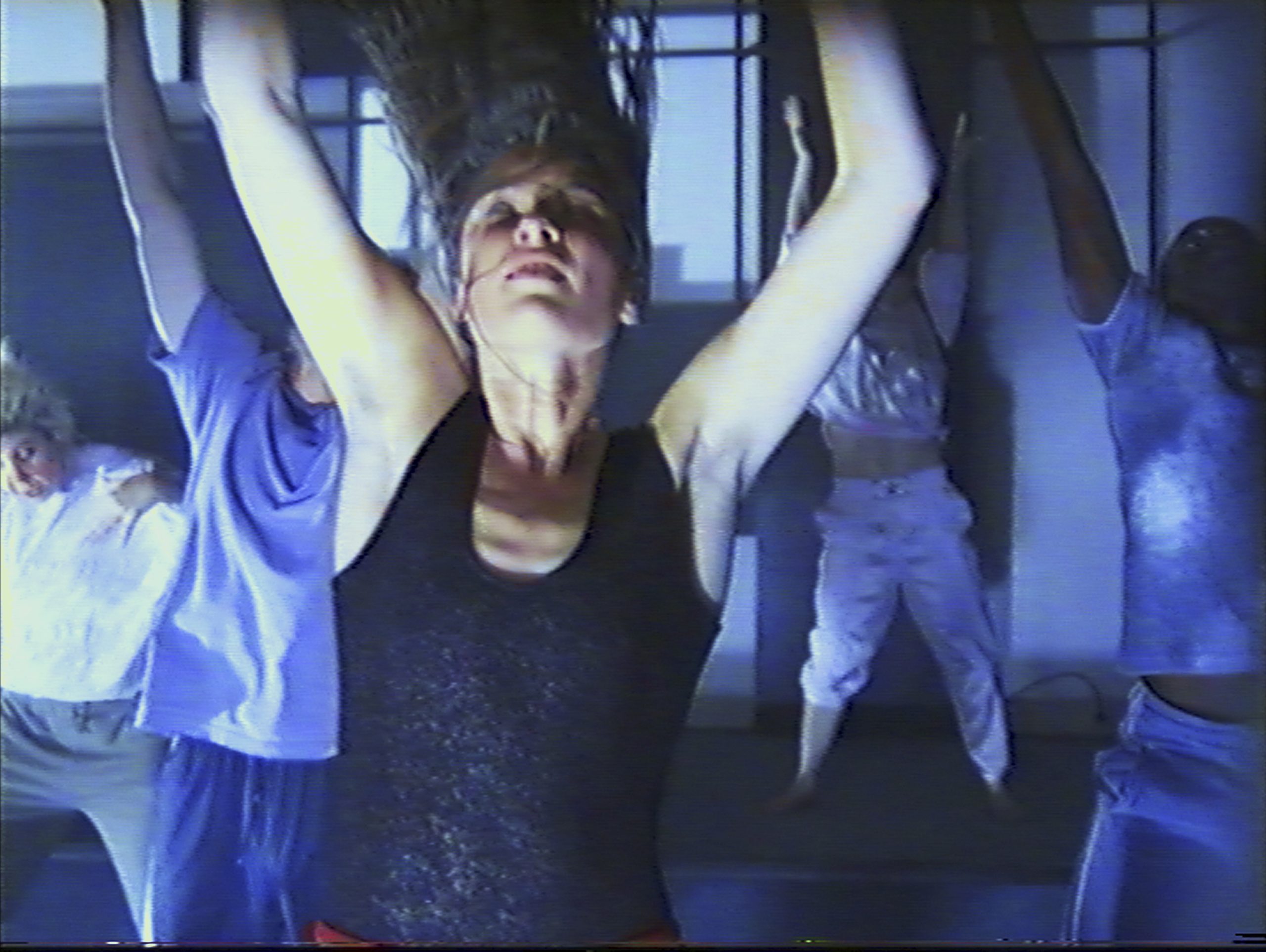

You mentioned during a talk with Hans Ulrich Obrist that you always wanted to remake “Altered States.” A horror film from the early 1980s based on sensory deprivation research conducted in isolation tanks under the influence of psychoactive drugs. Why this one?

Well, it’s truly one of my all-time favourite movies, but I’m not sure it’s such a good idea to attempt to remake it anymore. I mean, I used to think there were parts of it that I could somehow better, by either subduing or amplifying. But it’s such a fantastic film, and the things that I might have felt could be improved on years ago have actually become things that I love about it now. The flaws, or what I saw as flaws, are a huge part of its messy charm. These days I would much rather make a feature film of my own, from the ground-up, should I ever have that kind of a budget.

Let’s brighten the mood — I know you love dancing. What kind of music do you prefer?

I like so many kinds of music. My appreciation for music goes deeper than any other area of culture, I’d say, but it would be difficult to limit it to genres as I can find something that moves me in almost any form. In terms of dancing, everything from minimal synth-pop to deep trippy techno would be in my general selection parameters, but again, I am prone to dancing to almost anything that moves me.