JR in conversation with Elisa Carollo

JR, you’ve made a career in applying the guerrilla approach of street art to photography, embracing social causes and bringing them to the public’s attention. Creating powerful visual statements often in remote or unconventional venues, you have tackled both the public place and the public opinion at the same time on sensible issues of our time, operating on a singular intersection between the contemporary art system, politics and activism.

A question comes naturally: What kind of role do you believe art can and should have, confronting with today’s world? What kind of reaction or action are you looking for and expecting from your public, especially as you decide to operate in the public space, which I know you describe as “the largest art gallery in the world”?

I have always believed that the power of art lies in its ability to spark dialogue. With my work, I am not looking for a particular reaction from people, but rather I want to create interactions between people. That is why I paste in the street and do not sign my installations because I want the enormity of the work to stop people, make them pause and wonder, “Who is that person on the wall? What are they trying to say?” It’s up to the spectators to question and answer those questions themselves, to ask those around them if passers-by know what the installation is about.

I seek to have my work create as many interactions as possible because art alone does not change the world. The fact that art cannot change things makes it a neutral place for exchanges and discussions, and the streets have always been where an open, constant discussion can take place independently from any media and outside of any political party. Art can help us confront today’s challenges because it can change people’s perspectives, it can break down walls we build between us, and it can reconnect us.

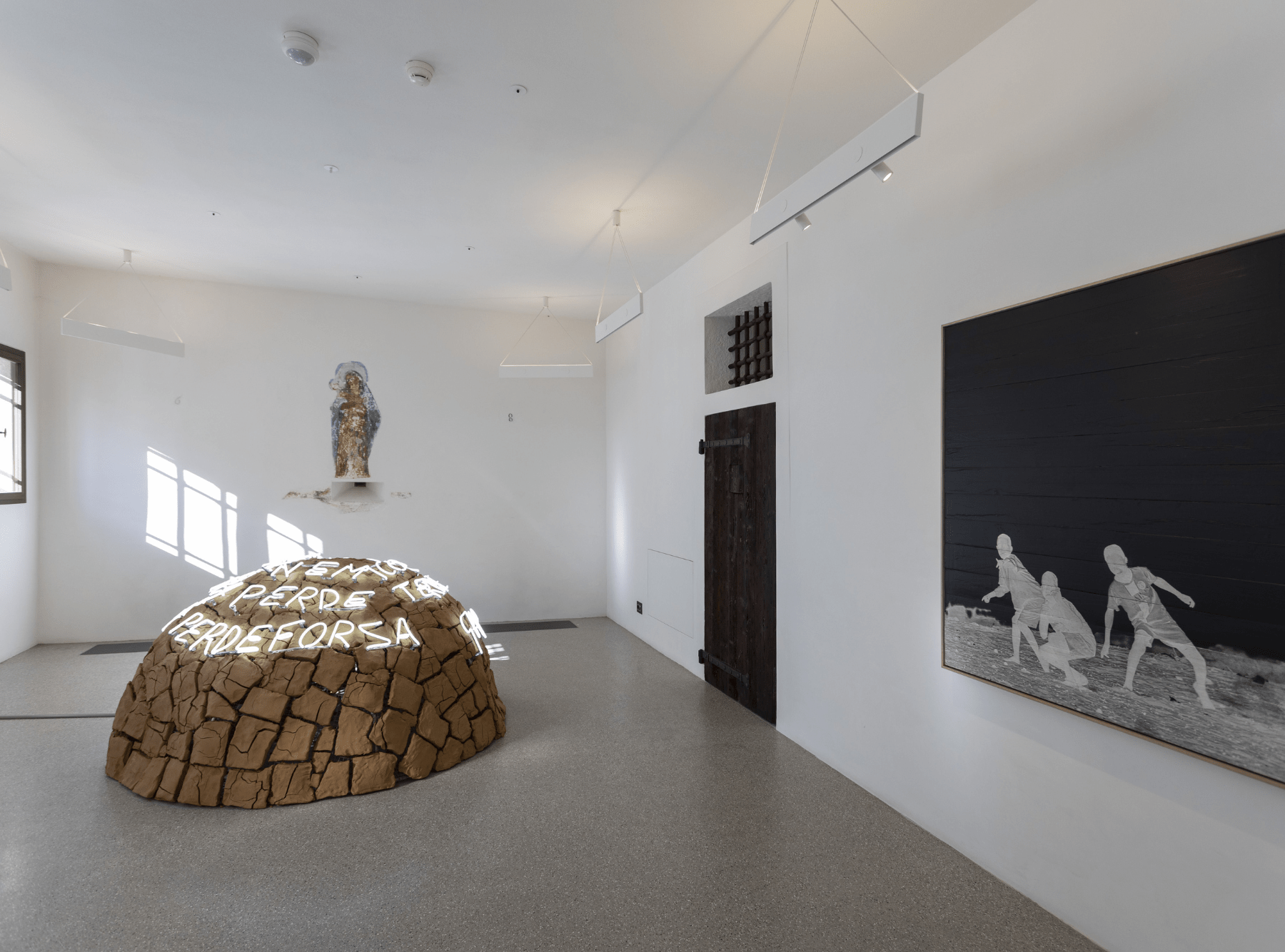

The works we have on view in the exhibition at Fondazione Imago Mundi in Treviso are part of Les Enfants d’Ouranos, your latest series of works which you presented earlier in March at Perrotin New York. The series originated from your ongoing project Déplacé-e-s, which shares the stories of refugee children from around the world, exploring the tensions between visible and invisible stories, in Today’s world history. With this series you’re bringing under the spotlight the stories of the most “invisible” and silent victims of the conflicts, who often cannot even have an opinion or a voice regarding what’s happening around them, dramatically affecting their lives forever. Can you tell us more about the Déplacé-e-s project, how you conceived it, and some of the most challenging moments you went through in pursuing it?

The project was a reaction to news headlines. On 24 February 2022, the start of Russia’s military offensive on Ukrainian soil triggered a major crisis in Europe and around the world. A war broke out overnight a few hours’ drive from my home and caused a huge displacement of people. I traveled to Ukraine before visiting refugee camps, talking to specialists from UNHCR (the United Nations Refugee Agency). I carried out the first stage of this new project in Lviv. It was not planned, it just came to me spontaneously. In Lviv, the idea was that Valeriia, the five-year-old refugee girl photographed, would be printed so that fighter jets flying above could not ignore the people below who need to be protected. The aerial photo of Valeriia caused a huge reaction and was the cover of Time magazine, but of course, there are millions of children stuck in refugee camps around the world and I wanted to continue to project in different places to amplify other groups’ experiences. One of the locations we visited was Mbera, Mauritania, where there is a camp of nearly 78,000 Fulani, Tuareg and Arab refugees, all from Mali, who have taken up residence in the Sahara. This camp is extremely remote, we drove thirty-six hours across Mauritania to get there, getting a flat tire in the middle of the journey. However, when we got there it was incredible to see this entire community set up in the desert. Many people there are unwilling to return home across the border. Some fled violence from jihadist groups, others the Malian army, and others still are escaping the direct consequences of global warming in the Sahel (extreme drought, crop failure, conflicts over resources). It is a kind of “two-speed” camp, where long-standing refugees have embarked on a process of empowerment, coexisting with new arrivals who are still in an emergency situation. We do not hear about the people living in this camp on the news. Meanwhile, news coverage about the refugee crisis in the media feeds us the same depictions of refugees over and over again. Displaying the enormous, joyous images of children in refugee camps across the world brings a different perspective, it asserts their humanity, it shows all the bright and innocent children full of dreams and aspirations.

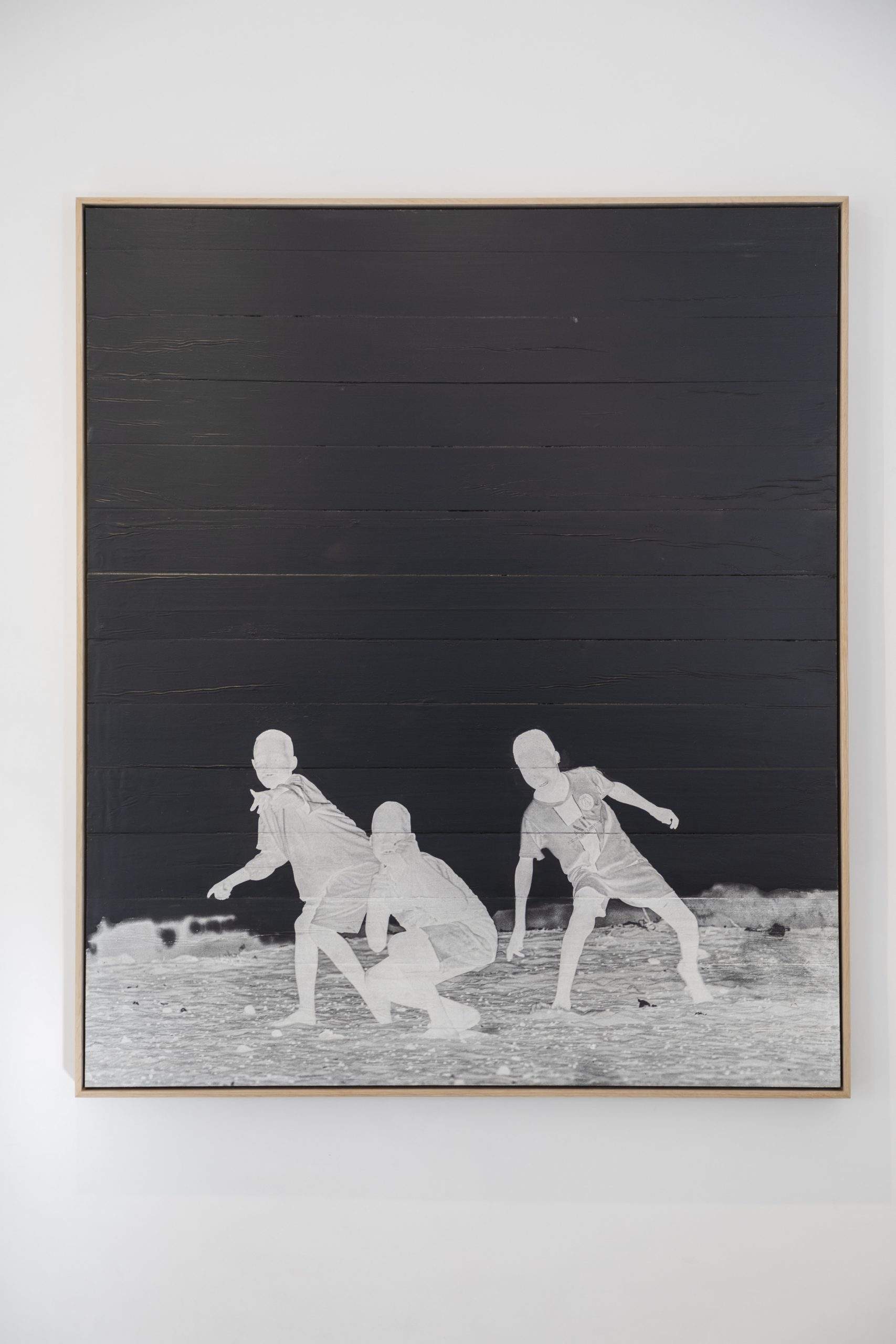

Talking more specifically about the new series, in the Les Enfants d’Ouranos: transferring negatives of each photograph on wood you’ve been able to create a powerful visual metaphors on the status of these kids, playing on a striking contrast between the light and the void, between their seemingly diaphanous presence, standing against the deep black of darkness. Through the dramatic use of black and white, these children’s depictions also eliminate cultural specificities and particularities, creating an iconic and universal statement. How do you choose the kids to photograph? Is this also part of a deeper process of human connection first (as you previously did) which starts with learning about their stories and only after deciding which ones to elevate to this status of universal icon of our unstable world?

The images used in “Les Enfants d’Ouranos” were all taken at the refugee camps I visited for the Déplacé.e.s project. I used the technique of transferring negatives in order to reverse light and dark, to convey a sense of divine, otherworldliness. Their depiction purposely blurs specificities and particularities, so a viewer cannot recognize where the children are. Whereas the printed banners in Déplacé.e.s present the children with keen clarity and highlight their innocence, the Les Enfants d’Ouranos images bring his subjects into a mythical realm, where they are in a moment of transition from childhood to adulthood, a moment when all possibilities lie ahead.

At the heart of your entire practice, there’s a big trust, agency and importance which you still attribute to the photographic medium. Photography is considered the first and arguably one of the best mediums to capture the reality as it is and in its happening. For that reason photos are also considered the best documents to report about the events happening in a specific historical moment, including wars. However, we know how this claim for truthfulness and objectivity has some defaults due to the possibility of manipulation, as well as to the inherent subjectivity of each gaze shooting a specific picture of the reality, but always from one’s perspective that excludes already some other points of view of the specific event. What’s your perception of the role of photography in documenting Today’ world events? How do you see your specific approach to photography, making it into giant visual statements in the public space, may expand some of its potentialities and remedy some of its inherent issues?

I don’t define myself as a photographer. For me, the pasting, the preparation, the installation—all of this is the art. The photo is the memory of it. Once someone asked me, “how do you get communities to trust you and understand what you’re doing?” and I told them that my secret is very simple. I just say hello, bonjour, and then we shake hands. When I photograph people I always ask for their consent, I ask them what they want to communicate, how they want to express themselves in a portrait. I think that this is the key, because I am not pushing a specific agenda, I am trying to capture a person’s story through their photo. With the pastings, I often work with no authorization and no sponsor, but more important that the legal authorization is the full full support from the people who are on the posters. Now when I conceive of projects, I try to involve as many people as possible. The main catalyst in my work is to reconnect people. Déplacé.e.s is not simply enormous photographs printed on a banner, it creates a moment that brings people together, and for an instant, everyone shares the same simple goal, to collectively lift the image. The art is the communities working collectively to carry the image, to lift it up to the sky and declare ‘we exist.’

PHOTO CREDITS

Installation view from Les Enfants d’Ouranos, solo show Perrotin, New York

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin. © JR. Photograph: Guillaume Ziccarelli

Les Enfants d’Ouranos #16 2023, ink on wood. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin. © JR.

Installation view from War is over! Peace has not yet begun , collective show, Fondazione Imago Mundi, Treviso. Photograph: Marco Pavan