Luca Rossi

January 2024

The art collective that falls under the name of Luca Rossi uses criticism as a paintbrush; over the years, they have given shape to a heterogeneous practice in the Italian art scene, often initiating debates that have translated into their artistic work at the intersection of Institutional Critique, multimedia installation and painting. We met them following their solo exhibition ‘Order a pizza from around the world and have it delivered to Galleria Six (Piazzale Gabrio Piola 5, Milan) on 16 December 2023 from 7 p.m.’ at Galleria Six.

After more than a decade of activism on blogs and social media, where you do not shy away from taking a critical stance, you claimed the role of who says that the king is naked. Almost beyond Institutional Critique, a now canonised current in art history, you have developed a critical system of various stylistic categories that you use from time to time to classify other artists’ practices. Given that this can also be an artistic practice – I am thinking of Boetti’s work, Manifesto, where he classifies many of his colleagues in more esoteric and poetic terms – your action seems instead to be a symptom of the absence of legitimate art criticism, at least in the Italian context. What is missing from the system to restore the figure and role of the critic? Why do you think it has to be an artist who says it?

I am deeply convinced that a public and fair critical context can be good for everyone and, above all, can renew the reasons and motivations in contemporary art, which otherwise (as has been the case for some years now) risk getting lost in derivative solutions and rigid and nostalgic attitudes. In 2009 I felt the need to stimulate a more critical confrontation, which I have been directing (on a daily basis for the last 15 years) first and foremost at myself. I was ready to ‘kill’ what I was before in order to be ‘reborn’. Every artist, young or mid-career, should be willing to do this on a daily basis. In 2023, indulging in mannerism and derivative languages means slipping into interior design and what I called ‘evolved IKEA’ in 2009. After 15 years, I realise that my critical work has forced me into a healthy isolation, a kind of quarantine that has protected me from certain toxic dynamics, allowing me to develop an unconventional design that also consists of training projects for artists and dissemination to the public. My criticism has become my first brush, and it seems important and necessary to me that this spark should come from an artist.

You define your work as “altermodern”, a category introduced by Nicolas Bourriaud for an exhibition he curated in 2009. Altermodernity is characterised by an interest in the ways in which content is distributed and managed, rather than in the content itself. All the more so as we are now faced with a saturation of physical and mental spaces, and density has replaced intensity, to quote again Bourriaud, who returns to this issue in his latest essay on capitolocene.

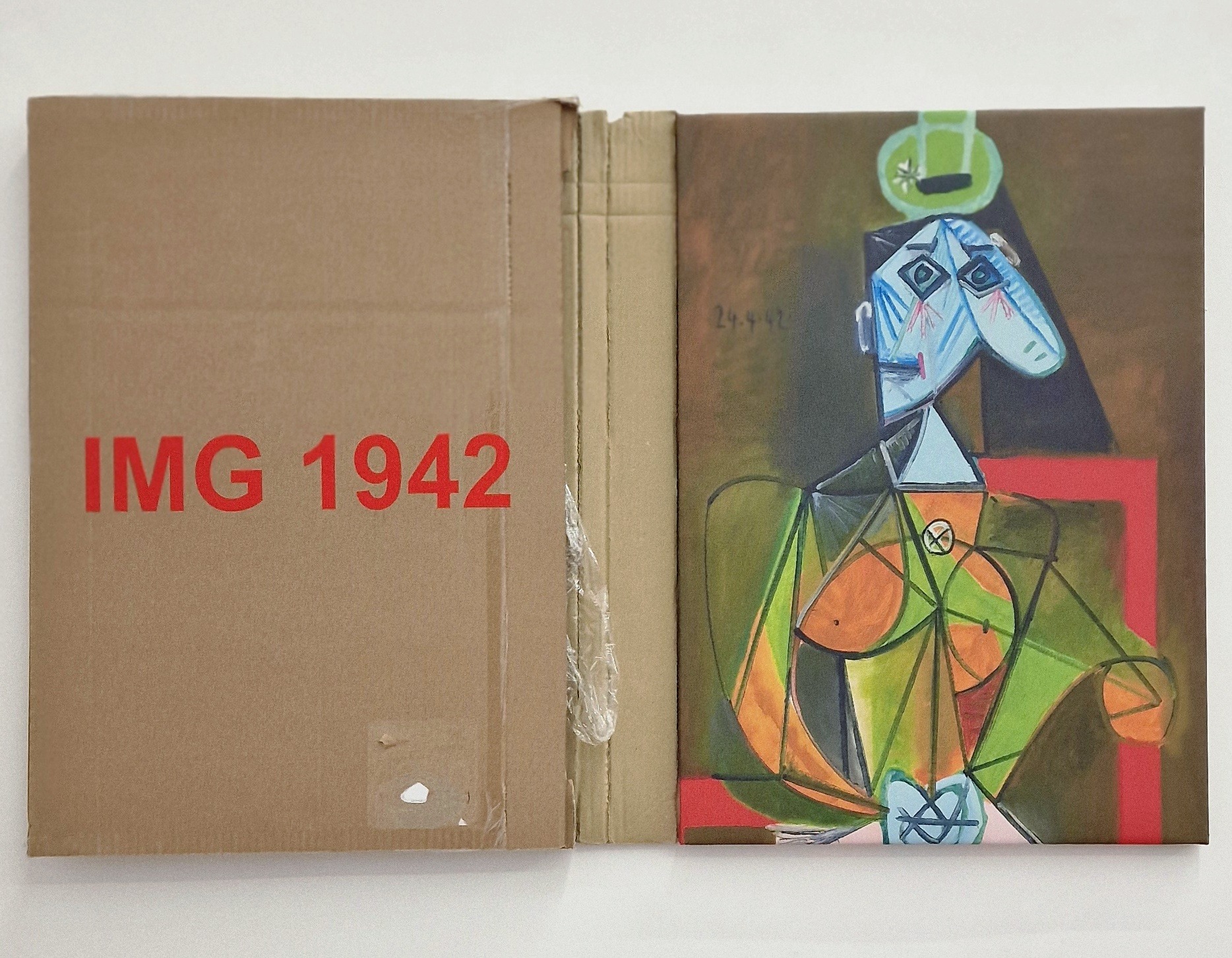

The ongoing series presented in the exhibition, IMAGES – If You Don’t Understand Something Search For It on YouTube, plays with this very aspect: the exponential growth of content created and uploaded to sharing platforms. The work consists of a series of alphanumeric codes that, when searched on YouTube, present us with dozens and dozens of different videos every day. With this operation, you are telling us that what art has to do has changed: from producing images that help us understand the world we move in, to producing ways of understanding how this world works?

The main problem we have today, inside and outside museums, is information management. We cannot address any problem, any issue, without first learning how to manage and organise the information of which we all are both creators and victims. Climate change, gender issues, wars, political and social problems cannot be addressed unless we first work on how we manage content and information. At the centre of my artistic practice is no longer the conventional postmodern work, but the management of information, on which I act as if it were ‘clay’ to be modelled and manipulated. The series you refer to presents works that focus not on creating yet another piece of content, but on sorting through the world’s bulimically produced information. This makes it possible to effectively represent our present and at the same time resist the dictatorship of the algorithm, which constantly feeds us with content that is already completely in line with ‘who we are’. In this way, the contemporary human being does not grow, but “gets fat”. Man grows, improves and is happy only when he is able to face the other and the different. On the contrary, the hyper-digitalised society in which we live puts us in a state of “anaesthesia” in which we are unable to understand and communicate; the Internet also makes us believe that we can move, even if we are only slumped over our screens.

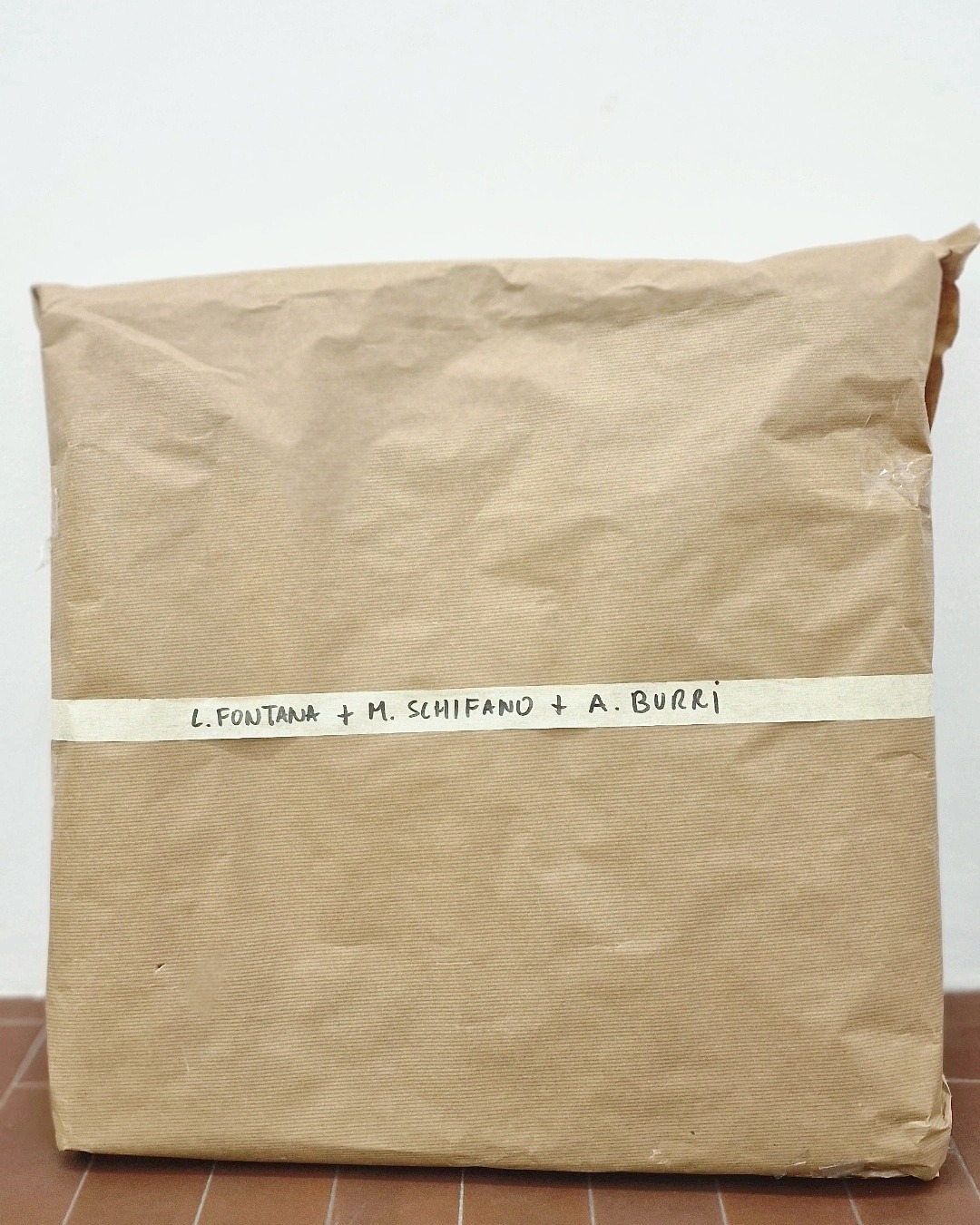

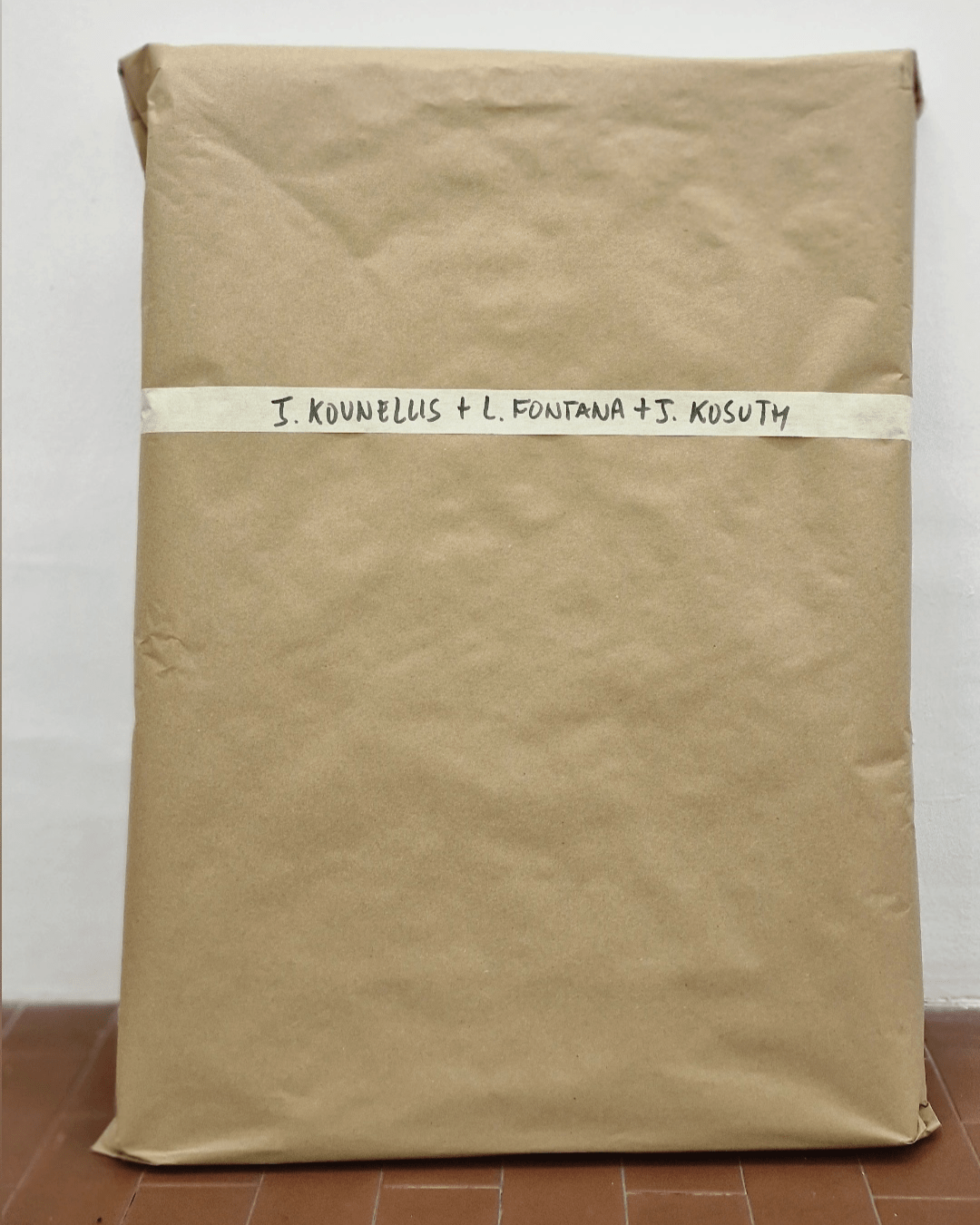

A similar reasoning is implemented in Hidden Works, another series in the exhibition, which consists of paper wrappings of works that we do not see and of which we only know the authors. They are works that have been subtracted from view and fruition, a bit like Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s packaging, the subtraction emphasises what is inside. This emphasis on material concealment reminds me of the reflections of the French sociologist Nathalie Heinich, when she theorises the shift of the concept of the contemporary from a chronological category, i.e. of artefacts produced in our era, to an aesthetic category, postulating the coexistence of modern, classical and even contemporary works. Without going much into Heinich’s elaborated analysis, contemporary works are characterised by being eminently discursive devices, i.e. the work is no longer so much in the material object before our eyes as in the narratives it triggers. It seems to me that this series (also) deals with this aspect.

Also in Hidden Works, everything is based on the management of information, i.e. the collector can choose three or more modern and contemporary artists to bring together in the same work, but the work is bought “hidden” and can only be opened when it arrives at his home. The collector could also decide never to open it. In reality, these works are not hidden, but protected by our present. In fact, each work reactivates our imagination, the effect of surprise and the value of anticipation, three aspects that the contemporary world is slowly suffocating through a constant “preview of reality”. We can know and have everything immediately, which kills waiting and therefore a very important space for reflection, depth and experience. These works resist some degenerations of our contemporaneity and give the collector a responsibility for the work, which can be hidden forever or visible in a certain way. In this case, too, the content is secondary to the management of information, even if, from a formal point of view, these works are very interesting exercises because they are ventures that take their author to totally unexpected and unpredictable places.

You have said in preview interviews that painting is perhaps the most interesting way of dealing with current challenges, and that it is perhaps the most authentically contemporary medium, despite the fact that it is a medium that you do not use. Do you still think so? In what way can it be?

Actually in 2019 at Galleria Six, I presented acrylics, which for me are in fact painting. I’ve always thought of painting as a third way, if the first way is the attitude of the altermoderns and the second way is working on ‘post-truth’. Painting can still be profoundly contemporary, although it is probably the most difficult way, precisely because the limits of the canvas allow the artist no shortcuts and force him to total awareness. Artists such as Michael Broughton and Luca Bertolo approach this third way in two different but equally effective and meaningful ways of reading our present.

PHOTO CREDITS

Luca Rossi, If you don’t understand something search for it on YouTube, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Galleria Six and private collection.

Luca Rossi, If you don’t understand something search for it on YouTube, 2023, Picasso’s replica purchased online, pre-spaced on an empty box. Courtesy Galleria Six

Luca Rossi, If you don’t understand something search for it on YouTube, 2023, Leonardo’s replica purchased online, pre-spaced on an empty box. Courtesy Galleria Six

Luca Rossi, Hidden Work (Schifano + Fontana + Burri), 2017, personalized work upon request or by random extraction of names. Courtesy Galleria Six

Luca Rossi, Hidden Work (Kounellis + Fontana + Kosuth), 2017, personalized work upon request or by random extraction of names. Courtesy Galleria Six

Luca Rossi, If you don’t understand something search for it on YouTube, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Galleria Six and private collection.