Martha Rosler in conversation with Elisa Carollo

You made a career being direct: without filters, you’ve been commenting and confronting society. Throughout your artistic practice you’ve unapologetically engaged in an open confrontation with the hard truths of our time, grappling on many fronts with its persisting injustices, from feminism to the contradictions of consumerist society, and of course, war. It appears that for you the artistic sphere is necessarily both shaped and bound up with the political forces in society, rather than providing a means and a space to evade those forces, as art was traditionally conceived. But, having created and still creating highly political works, do you see your art actively operating as an activist tool, or is it more intended to provide a commentary for the purposes of encouraging critical awareness? I know you’ve described your works as “mechanisms to activate viewer’s ideas”, encouraging an “active reflecting attitude” – which seems more like how Socrates’ maieutic approach would work.

The idea of art as transcendent and divorced from social struggles and events is very particular to Modernism and has had a very short life–maybe a century? Artists had already begun to abandon this retreat from direct social engagement soon after the Second World War. It’s true that in the US, High Modernism remained powerful for a long time, and the movement that supplanted it, namely, Pop, appeared to celebrate rather than criticize popular commercial culture. But Pop, especially the kind practiced by women, almost inescapably provided a jaundiced view of Pop culture imagery, especially of representations of women. This was a critique of the power of consumer culture to negatively affect women’s social standing. I trace some of my work to this kind of engagement with popular representations in the mass media, especially the popular press, of “Woman” and her supposed domain, the home and family—but also my photomontages utilizing the representations of war, placing them in close proximity to the images of those sparkling-clean and alluring homes being sold to middle-class women. It is a pleasure to accept the idea of a maieutic approach, one of helping the viewer birth an idea, as the term ‘maieutics’ refers to midwifery, of which Socrates’s mother was reportedly a practitioner, as you surely know.

The series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, which we are showing, is probably one of the most iconic works you have made. Notably, the Vietnam war has been described as the first “living-room war”, observed daily on tv. New media bring the war close to our lives, first with tv and then with social media, but at the same time this has paradoxically generated also some ability to distance from it: making the war an ordinary presence at home, allowed a normalization of the tragedy, justifying it as “foreign violence”, namely something perceived as far, remote and other. This desensitization is a problem for many conflicts happening now and in the last decades: the low perception and awareness of gravity for the rest of the world, which is interconnected mediatically, but progressively sentimentally disconnected. What’s your opinion on this? How has this evolved since your first anticipation in the first edition of the series in the 70’s, to the second, and to today’s world?

The antiwar photomontages that fall within the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home evolved out of the series of feminist photomontages that preceded them. These were images of women drawn from magazines that I put together or “adjusted” in various ways, and that group of images falls under the title Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain. To turn now to just the antiwar photomontages, I think the “collision” of images within these photomontages—characters in a war, against the surroundings in which the viewer finds them— will always produce a certain shock of incongruity in the viewer. Sometimes the images are of people from “our” world, that of the home and everyday life, who are ‘dis-placed’ into scenes of the war zone. In all these photomontages, I am trying to insist on the link between the two: between “us” and our idealized beautiful and “safe spaces,” and “them”: those who live in constant precarity and are not entitled to what we have been privileged to attain. Until we truly understand that the world is not actually divided into the “here” and the “there” but in fact is one, wars will not end—and certainly we must also note that unless we understand the unity of the world, we will never solve the crises of global warming and the migration and conflict they engender.

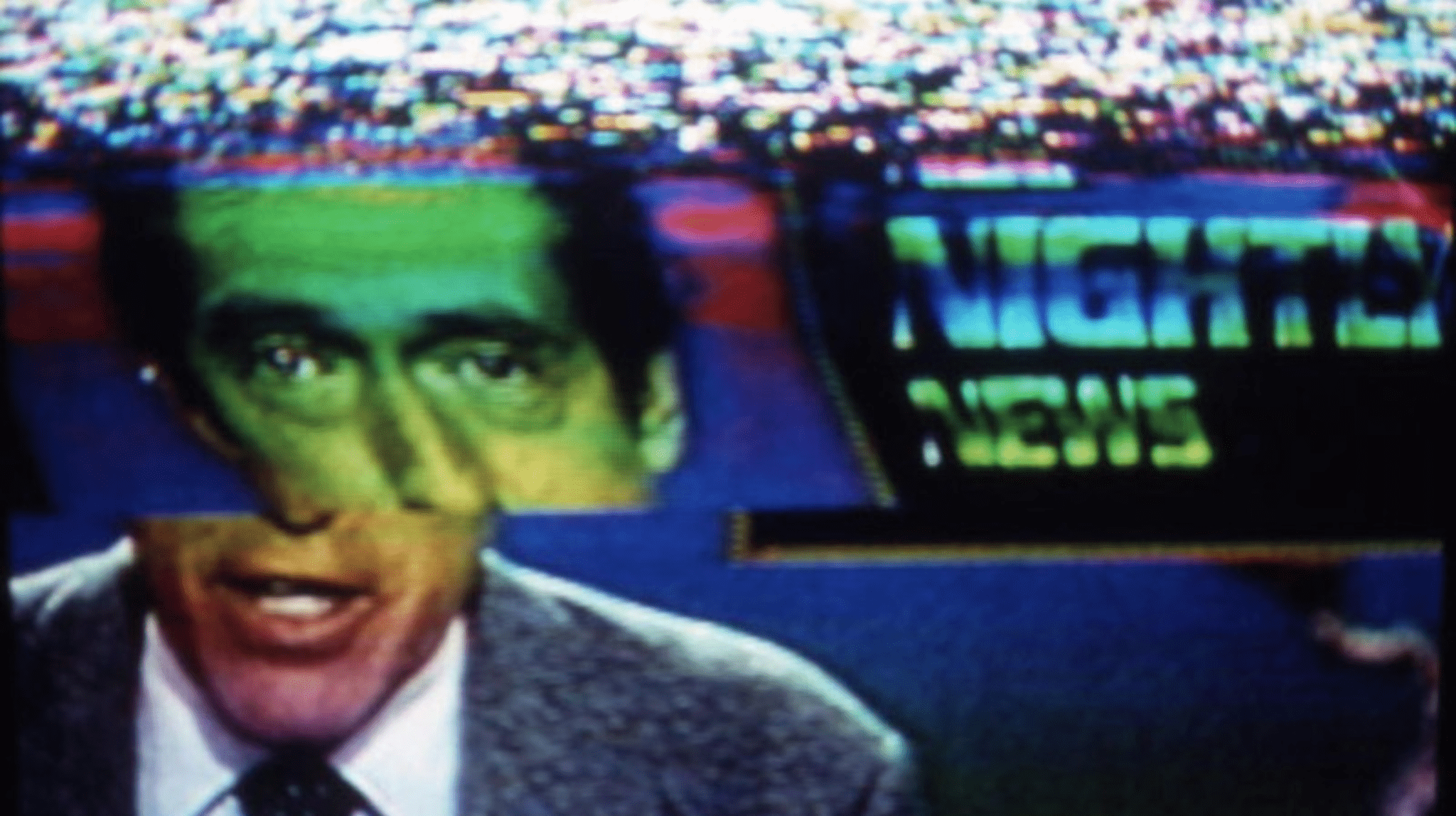

History, and especially wars, have been mostly narrated from the winning side, and controlled with a specific narrative of it. This is true from the first known war reporting by Herodotus, to the Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan war. You’ve been unmasking these media mechanisms in many of your works, such as purposely sabotaging some of the narrations on your works as with the video If It’s too Bad to be True, it could be DISINFORMATION (1985)— a work with already a quite telling title, addressing a space of no credulity of authorized and institutional tales. Some have commented, in fact, that the media have contributed to blurring the lines between the plausible truth of the fictive and the factual one of the historical narration, as once described originally by Aristotle, generating this confusing hybrid of “Fictual”. Then social media, and especially Instagram, have somehow changed the rules of the war-fiction game, allowing real people to report and tell their stories from the areas of conflict —of course, if not obscured and disconnected by censorship. Having worked a lot with the distortion of narratives and messages through controlled media, what’s your view on this new empowerment of the witness and of creators, social media brought rapidly as an alternative of traditional media reporting?

The technologies of war reportage have been steadily increasing their presence in our lives and are constantly evolving. But the cellphone camera today is still the primary means of direct reportage from nonmedia, nonjournalistic sources if that’s what you mean by ‘real people.’ I must point out the powerful role of cellphone cameras in exposing the degree to which police in the US have been killing people of color, often young men, and often with no real justification other than that the police have guns and other weapons and, more importantly, that they are empowered to use force on the thinnest of excuses. (Three of the recent, high-profile police killings were accomplished by choking people to death,or beating them to death with fists and batons.) In Ukraine, cell phone camera testimony has also been very valuable in exposing Russian war crimes. Nevertheless, as we can see from the deep fog of lies blanketing the Russian people at home, the power to control the story still lies in the hands of those who control the media, including the internet. The manipulation of news media by a fanatical driven right, generally bankrolled by very rich people, is common in many, many countries.

Getting back to your iconic series we are presenting, the critical collages you created could be also read as a harsh critique of an idealization of domesticity made comfortable for women (always present as main characters) by the consumerist society, but at the same time reconfirming in its iconology a “mechanism of domestication of women”, in a male dominated nuclear family. You’ve been often addressing those topics, all over your oeuvre. Things have certainly been changing (at least in most of western society) since your early feminist works, such as the video Semiotics of the Kitchen, but many battles for gender equality are still to be fought, as Iran with the first women-led revolt in the Middle East showed us. We had many religion-based conflicts throughout history, as well as many ethnic-based conflicts which are still happening. But do you think we will ever see a war run by women, against the patriarchal system? Do you consider these protests in Iran a sort of civil war? What’s the Feminist battle, today?

Do I think we’ll see a war run by women? We can follow the model of the fictional Lysistrata, but does that qualify as war, or as social pressure? Among the Kurds of Rojava, in Syria, the women not only are noted fighters, they are also leaders in the development of forms of gender-equal libertarian socialism. In Iran today, the mass protests initiated by young women (and quickly joined by their male counterparts, while still being primarily driven by women, and even joined by their aunts and mothers!), follow the pattern of a social revolt and mass uprising in a society of rising expectations that are not being met. Revolutions happen that way, not “civil war.” But much as I deeply admire and support the many acts of revolt of these women—my Facebook profile picture is that of Masa Amini, stupidly killed by Iranian morality police—I do not know how to predict what the course of events in Iran will be. The state is still very powerful, and many people in the streets, including children, have been killed during their effort to bring about change. The state may well decide to drop the insistence on the hijab—or it may not. There are internal disputes within the regime itself, of course, over how to proceed. I am not at all sure what will determine the outcome. We can surely join Iranian women and their allies in their rallying cry, ‘Women, Life, Freedom.’ To answer your further question: The feminist battle today—everywhere!— is to insist on full equality of all persons under the law, on social equity, but at the same time a recognition of the special tasks that have typically fallen to women. This is not news: it is a very long-standing battle—already 50 years ago some termed it ‘the longest revolution’—but it constantly bears repeating. Societies, and I am speaking here primarily of moderate and high wealth societies, really should speed up the rethinking of all elements of human organization and to “denaturalize” the forms of family association and family life that we have inherited, as they so clearly fail to serve us in the present. There is no question, of course, that essential to women’s full entry into the role of functioning adult is the absolute right to sovereignty over our own bodies, and the end to the patriarchal assumptions about sex and gender, childbearing, and childcare. This also means that violence against women, whether within the family or perpetrated by anyone else, must be taken seriously and relentlessly prosecuted by the law. This is not to overlook the fact that the gender spectrum is now recognizably extended to many different permutations that must be acknowledged as equals as well. And I hope it goes without saying that the education of boys and men must also be developed to radically rebuild social expectations and behavior. Hugely important consumer industries, especially fashion and cosmetics, depend on the continuing objectification of women, made all the worse during the pandemic by the role of Instagram and other social media in the lives of young women, throwing us backward in terms of the need to help young people free themselves from the expectation of subordination to the sexualized, power-driven gaze. It is well past time to pay attention to this!

As some critics and especially semiologists have commented (ref. Antonio Scurati, among the others), today we largely live in a literature and media narration of “no-experience”, which allows the viewer this “transcendence” from the real facts happening, as always perceived remote, filtered by a screen that protects from reality be affected and worried about the gravity. Once again, we can see this happening also with a progressive desensitization towards the conflict in Ukraine, which is still going on after a year from the invasion, but it is no more on top of media news, especially in the US. How should war be narrated to keep people aware and engaged? What can be the role of art, if not providing solutions, but at least to raise awareness and keep the attention around today’s World problems?

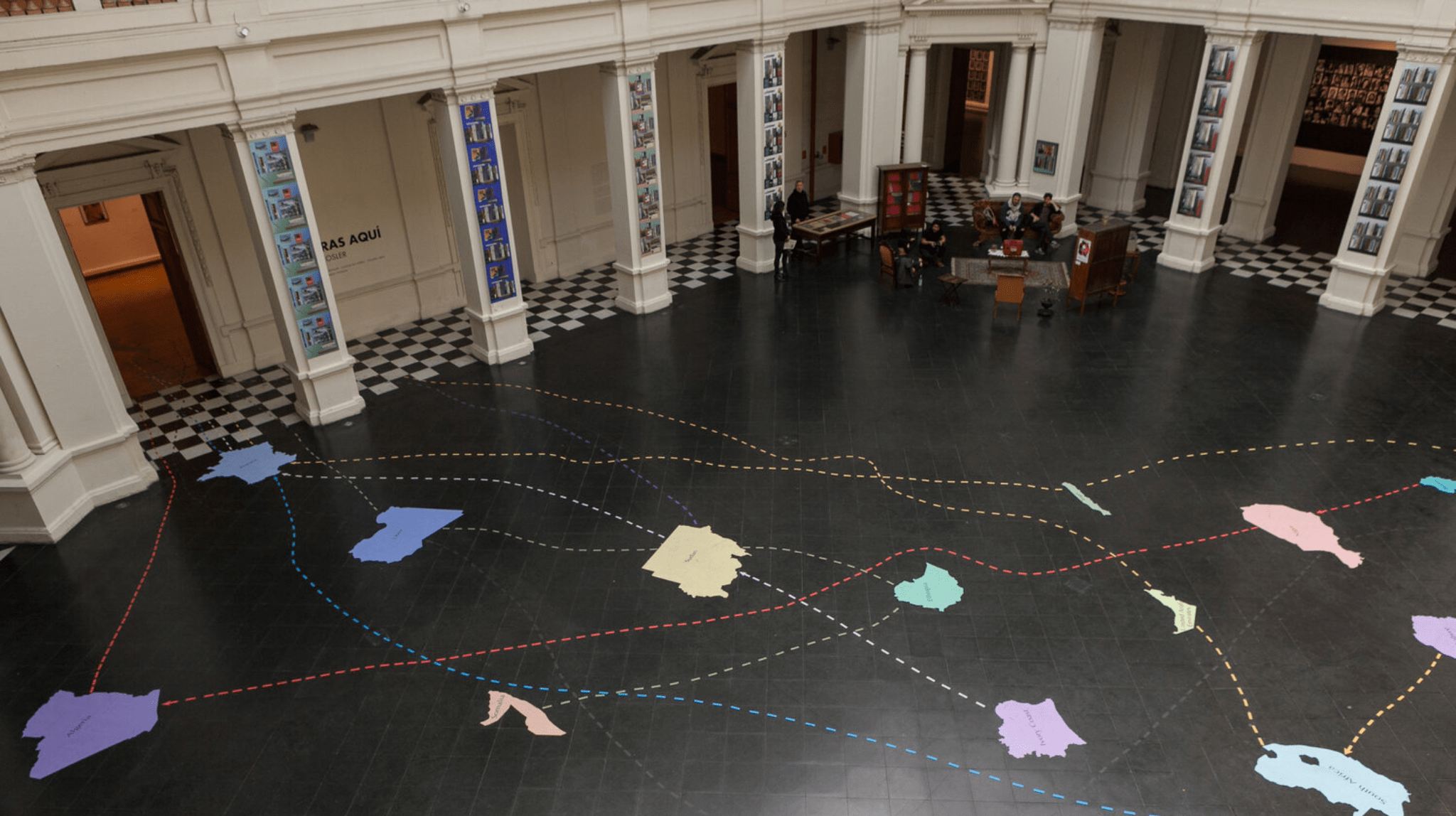

First, I’d like to note that the war in Ukraine is very often in the US news. But you ask, “How should war be narrated to keep people aware and engaged?” The well-established way—the best we have at present: with reporters on the ground, reporting daily, and the news anchors and those who take part in programs that discuss current issues continuing to talk about it. The stakes of the war especially in relation to the future of Europe must continually be explained in a clear manner; it is wise to provide the human-interest stories in which life in a war zone is told by those experiencing it. Interview refugees from the war in Ukraine—after you allow them to find a place in Italy or elsewhere in Europe—and interview as well those poorer migrants who have the unfortunate fate of being caught up in wars and conditions of economic devastation outside Europe, in the global South—those who must risk death by migrating in shockingly precarious ways across the Mediterranean to seek a life in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. About ten years ago I did a work in Torino called Invisible Labor, based on interviews with young women from Nigeria and their complex and difficult journeys to Milan, where they found themselves working in the sex trade. (The interviews with young men from Sub-Saharan Africa were mostly about their new lives in service industries.) Today, however, the patterns of migration seem to be quite different, as both war and climate (and therefore economic) devastation have intensified, and xenophobia is rising. It’s horrifying and distressing that Italy, for example, now is led by a party with direct links to the Fascist Party, with no real reason to support Ukraine but rather to continue purveying their rather successful xenophobic narrative of the invasion of Italy by dark-skinned, non-Christian foreigners and its echoes of the essentially racist attacks on people from Italy’s south. Art can be most powerful and compelling as an adjunct to other voices, the voices of reporters and victims, of advocates and activists, and as a supplement to people’s efforts to demand better from ourselves and our governments.

This interview was conducted in March 2023.

PHOTO CREDITS

Semiotics of the kitchen, Courtesy of the artist

Point and Shoot, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, 2008 Photomontage. Courtesy of the artist, Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Invasion, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, 2008 Photomontage. Courtesy of the artist, Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

If It’s too bad to be true, It could be disinformation, Courtesy of the artist

Invisible Labor, Courtesy of the artist