Massimo Bartolini in conversation with Mattia Solari

In his artistic practice, Massimo Bartolini works with architectural installations, performance, sound, photography and video. After the degree in surveying, he attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence, but it is theatre that has most influenced him. Interested in the action of space and the actors who inhabit it, Bartolini creates works that explore the perception of the spaces we inhabit, in a balance between spiritual meditation and disinterested observation. Music and landscape are two of the most recurring themes in his site-specific works, contributing to the creation of unusual environments that play with the viewer’s perceptions and sensations.

I would like to start by talking about the work in the exhibition, Horizontal Victory. I imagine that, as with all your works, there was a period of research that preceded the formalisation of this work. From the pattern that covers the work, in which two different military camouflages are superimposed, making camouflage impossible, to the disembodied object in listening, as you yourself defined the sculpture lying on the piano, absorbed in listening to silence. I would like to ask you what inspired you to investigate musical instruments and their relationship to war, and how you came to discover and choose the pianos made by Steinway & Sons for the US Army.

Camouflage comes from two different wars: The Second World War and the Iraq War. In the first there was already the other. As is often the case with me, the inspiration for the work came from a book called “In Search of the Perfect Piano” by Katie Hafner. In it, the author glancingly mentions Steinway & Sons as a manufacturer of gliders for troop transport; in fact, they did not fly well and the soldiers used the giant glider boxes as living quarters. From there, through research and selection of the abundant material I found, I designed a series of works, of which Horizontal Victory is the only one that has been realised.

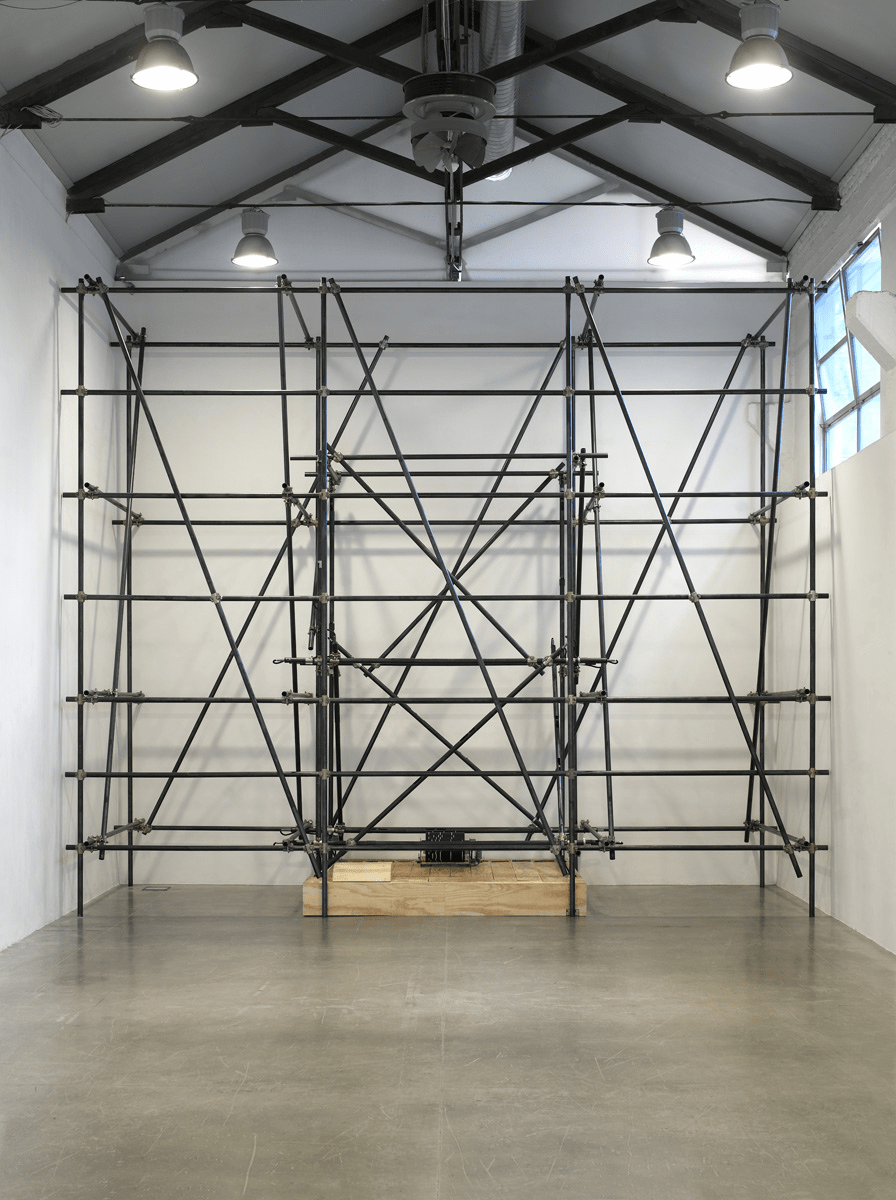

In your practice you have often reinvented the media you use in unorthodox ways, I am thinking of the illuminations in La strada di sotto (The Street Below), 2011, the scaffolding and the organ in Organi (Organs), 2008, as well as one of your best-known works, Untitled (Wave), 1997-2001, or your early interventions such as Casa di Francesca Sorace (Francesca Sorace’s House), 1993. In these works, you borrow objects to alter their functionality, creating new meanings that challenge common perceptions of objects and their surroundings. Subverting functions, codes and meanings reminds me of the notions of strategy and tactics used by the French anthropologist and historian Michel de Certeau in his most famous book, The Invention of the Everyday. Both are peculiar ways of acting in social space, the former used by hegemonic classes to maintain their power, the latter by passive consumers who, through calculated actions, carry out defensive and opportunistic actions to present forms of radical otherness and resistance to power; this is why Certeau also defines tactics as the art of the weak. Do you see your artistic actions somehow in this reflection?

Neither strategy nor tactics… I’d like to be able to clean and light a place well. To be honest, my work doesn’t have much of a social aspect. I like to think that changing, moving, connecting one or more objects reveals one aspect of the same object and hides others.

In 2010, together with Stefano Arienti, you curated the exhibition -2 +3 at the Museion in Bolzano, in which you moved some of the works from the museum’s archives from storage to exhibition space. In recent years, much has been written and reflected on the differences and permeability of the roles of artist and curator. What do you think the role of the artist has to offer the role of the curator and, conversely, what do you think the work of a curator can offer the practice of an artist and, in this case, your practice, which is often concerned with space and environments?

In schools, students very often are both. They do not perceive the differences and I agree with them. You curate exhibitions as artists and you make works by curating forms of intensity. I think that today this is an obsolete distinction that only serves for communication.

Going back to the exhibition in which Horizontal Victory is displayed, for me including this work meant having an additional piece that could describe how war is not only made by weapons on the battlefields, but also through other instruments, in this case music, that become functional for the war effort. So to talk about war is to talk about human nature in 360 degrees. How do you think art can respond to this dramatic subject? What is the answer to the famous “What to do?” that, from Lenin’s pamphlet to Mario Merz’s work, questions human action?

My answer would be for everyone to make the moments of enchantment that happen to us in life last a lifetime.

PHOTO CREDITS

Massimo Bartolini, The Street Below, 2011

Massimo Bartolini, Horizontal Victory, 2022 Installation view, Fondazione Imago Mundi, © Marco Pavan

Massimo Bartolini, Organs, 2008

Massimo Bartolini, Untitled, 2008