Features #23 - September 2023

Willem de Rooij: interview

WILLEM DE ROOIJ IN CONVERSATION WITH NICOLAS VAMVOUKLIS

Willem, I must confess that I’m obsessed with flowers in art, and of course, when I think of your practice, the “Bouquets” come first in mind. If I remember correctly, there are 11 pieces individually open to an ongoing ‘translation.’ How has this series evolved throughout the years? Have you considered forming new pieces?

I began working with flowers together with Jeroen de Rijke, with whom I worked as an artist duo from 1994 until he passed away in 2006. Having grown up in the Netherlands, where much of the land is reclaimed, our relationship with nature was a complex one. The export and cultivation of flowers go back centuries and play important roles in Dutch cultural identity. At the same time, flowers became containers for all sorts of metaphorical content. So, rather than natural entities, flowers seemed to exist as concepts to us. We began to make Bouquets to test whether it’d be possible for any object or flower to take on any possible meaning or serve any agenda. The series that evolved and that continues to develop, in its essence, is always concerned with this question.

I know these sculptures are developed with the collaboration of florists, and I find it engaging how you often include works of other artists in your own artworks in many different ways. What is your idea of collaboration?

For me, art is a discursive activity, so it involves more than one party: it’s something that happens through exchange. So, having other voices present in the work is inherent to my understanding of art. The team at my studio – photographers, florists, weavers, writers – each encounter adds meaningful traces to my work.

In the way that democratic processes, or the upkeep of public institutions, are importantly defined by compromise, so is collaboration. That means that no party gets exactly what they want. And even though magnificent opportunities arise out of compromises, they are also really hard to establish. It means that there will be struggle, disappointment, exhaustion, and frustration.

You have been a Professor of Fine Arts at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main for almost two decades. How do you approach teaching, and what advice would you give a young artist at the start of their career?

I work in academia because I like to communicate, not because I like to lecture, so I see myself as a conversation partner rather than an advisor. Also, each individual artist that I meet is so different it’d be impossible to give blanket advice…

Personally, I am grateful every day for the support that I received as a young person, and I really believe it’s important to return that support. I would advise anyone, whether they are a young artist or a young baker, or a young nurse, to remember their beginnings, to invest in long-term relationships, and to give back to their professional ecosystem whenever they can.

In 2016, you co-founded the BPA// Berlin program for artists, facilitating the exchange between emerging and experienced practitioners. What are the qualities of a good mentor?

After finishing art school, I spent two years at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam: a residency where emerging artists meet more experienced colleagues to exchange ideas at eye level. Being surrounded by ambitious international peers in an environment that was both supportive and competitive sharpened the way I saw my work and helped me define my goals. These experiences, amongst many others, inspired the first concept of BPA//.

A mentor cannot come to a productive meeting without an engaged mentee. So, for a program like BPA//, the selection of mentors and mentees is important, but the meetings between them, a dynamic that can hardly be planned, are the most important thing. Meaningful content develops in dialogue.

“Root” is a new installation you developed, especially for Galerie Thomas Schulte, that will be on view during the Berlin Art Week 2023. What is it about?

We exhibit a seventeenth-century painting by Dutch artist Willem Frederiksz van Royen, depicting an anthropomorphic carrot. Van Royen worked in the tradition of still life painters such as Melchior d’Hondecoeter, Jan Weenix, and Dirk Valkenburg, who promoted the Dutch Empire and its extractivist policies. These artists often worked for and with each other, quoting each other’s forms and techniques. In response to Van Royen’s painting, I produced a number of images using AI image generators. Since these machines, by their nature, produce amalgamates of many images made by many authors, the process felt connected to the way that Van Royen and his colleagues co-developed genres and forms. At the same time, these visual constructs echo the Dutch tradition of producing artificial nature.

Which would you say are your common grounds with Willem Frederiksz van Royen?

So many, besides our names! We both grew up on the North Sea coast, west of Amsterdam. Our work urged both of us to move to Berlin, where we both became active in art education: Van Royen was one of the founders of the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1696, and I founded www.berlinprogramforartists.org together with Angela Bulloch and Simon Denny in 2016. Van Royen’s work was importantly influenced by Melchior d’Hondecoeter, whose work I exhibited at the Neue Nationalgalerie in 2010 and about whom I produced the most comprehensive publication to date.

I think the differences between us are sitting in the way we see our native country: Van Royen was brought to Berlin to promote Dutch culture, while I experience my own relationship to national identity as more complicated.

PHOTO CREDITS

1.

Willem de Rooij, Bouquet IX, 2012

Spheric arrangement of 10 different species of white flowers, white ceramic vase, written description, list of flowers, Private collection, Panama

Installation view: Bouquet IX, Delgosha Gallery, Tehran, 2021

Photo: Delgosha Gallery

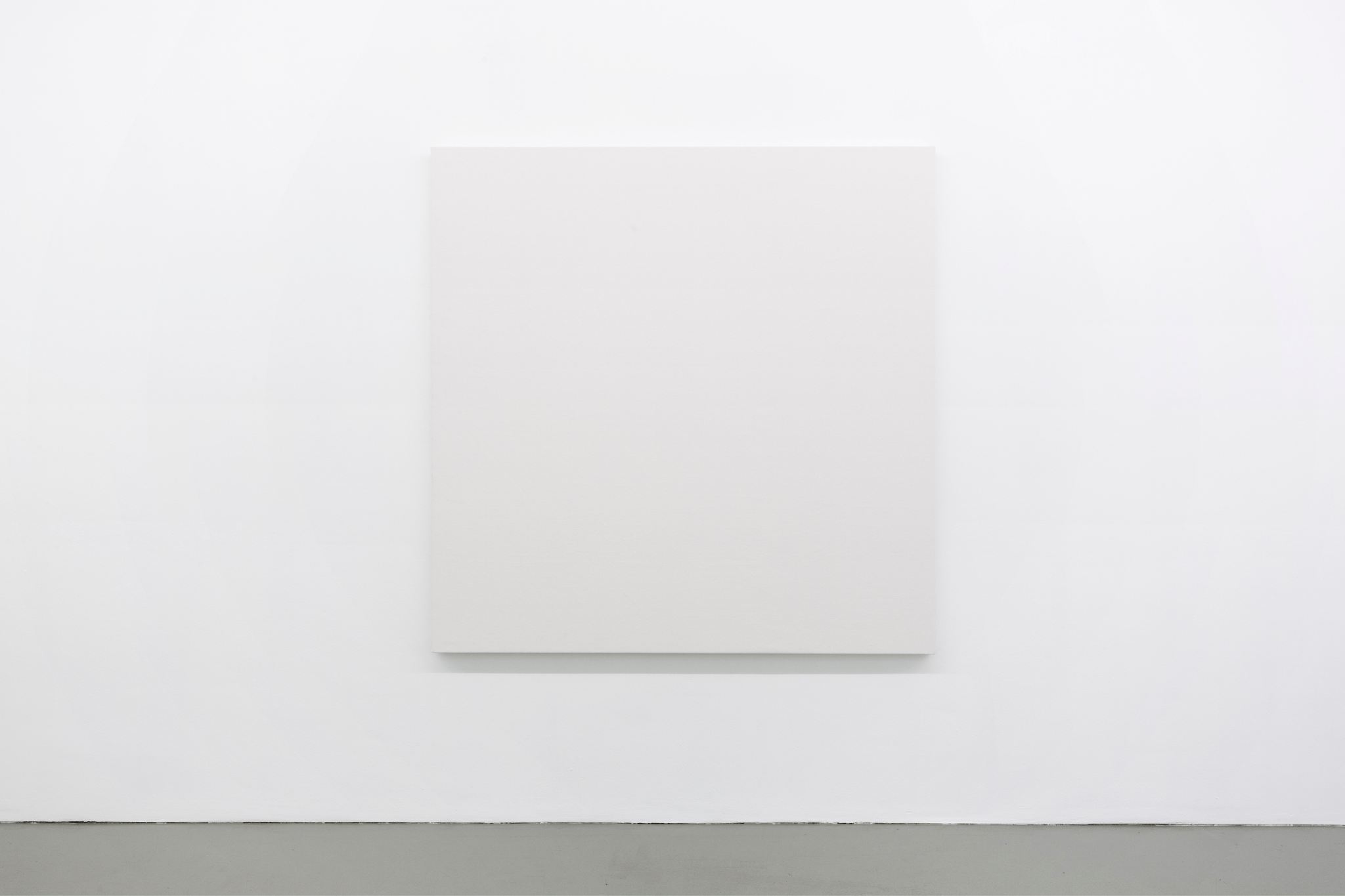

2.

Willem de Rooij, Whites, 2021

Hand woven tapestry on wooden stretcher, 170 x 170 cm

Installation view: Flare perception, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, 2022

Photo: Sonia Mangiapane

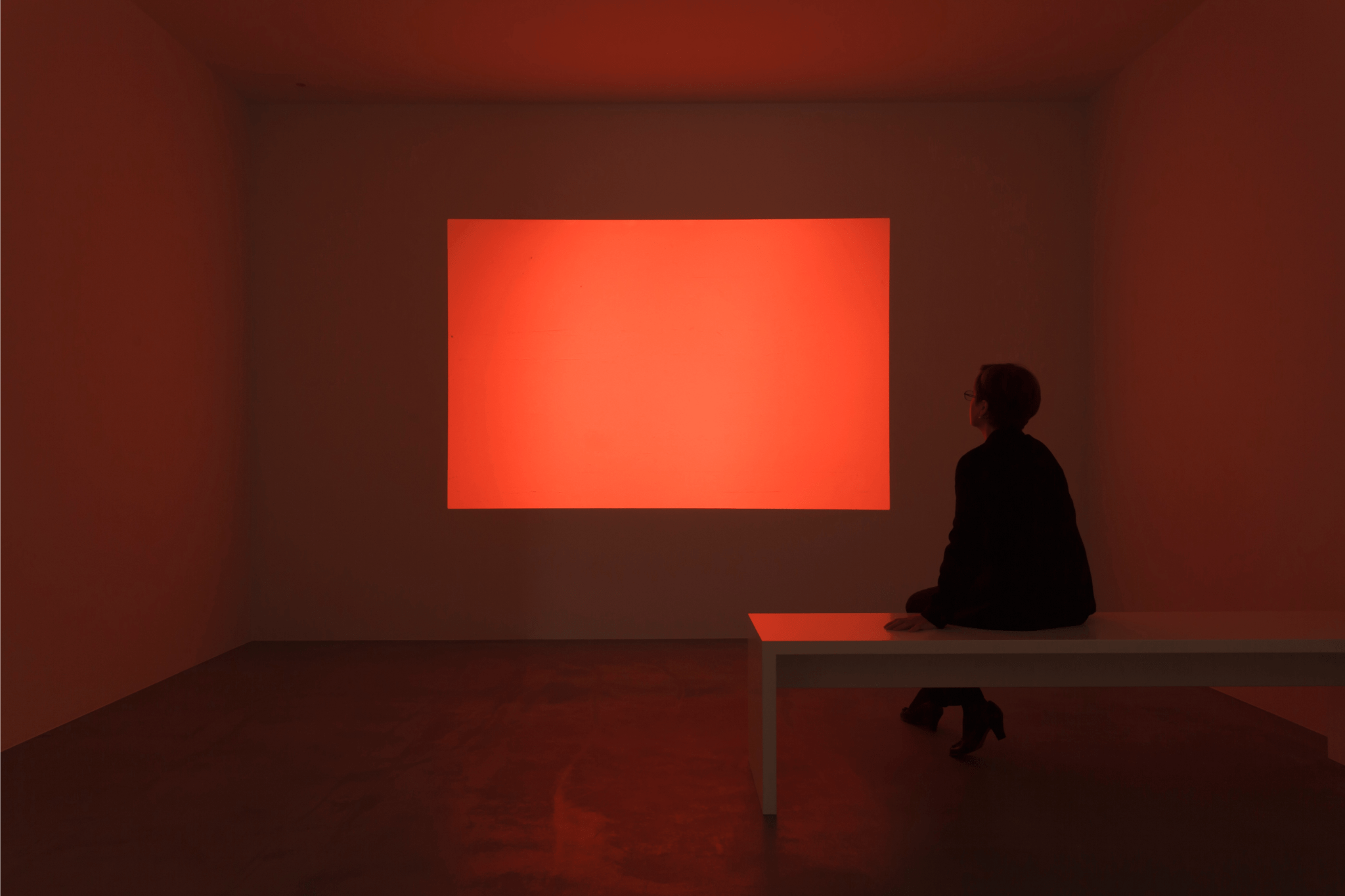

3.

De Rijke/De Rooij, Orange, 2004

Sequence of 81 35mm color slides, soundproof box, wall text

Installation view: Entitled, MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, 2017

Photo: Axel Schneider

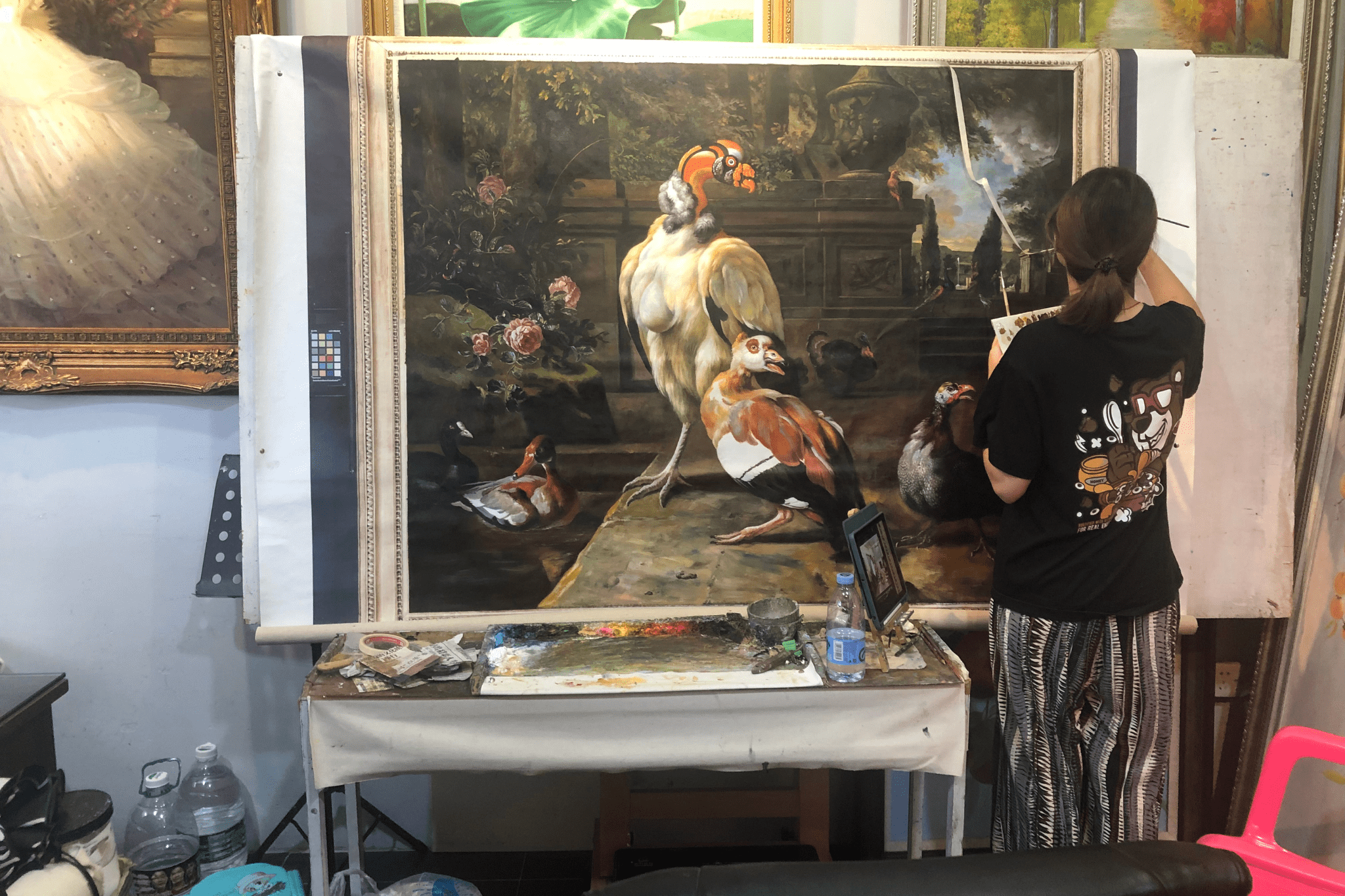

4.

Yaohui Zhu painting documentation of Jan Weenix’ Exotic Birds in a Park (1702) at Yunxi Art Studio, Dafen, 2022

Photo: Yunxi Art Studio

5.

Jan Weenix, Südamerikanischer Königsgeier/South American King Vulture, ca. 1700

Oil on canvas, 117 × 98 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Willem de Rooij, Documentation of Jan Weenix’ Exotic Birds in a Park (1702) from the collection of the Szépművészeti Múzeum/ Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest by anonymous photographer, painted by Yaohui Zhu and team for Yunxi , Art Studio Dafen, 2022

Oil on canvas, 176,5 x 140 cm, Ringier Collection, Zürich

Installation view: King Vulture, Kunstsammlungen der Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, 2023

Photo: Iris Ranzinger

6.

Willem Frederiksz van Royen, Rübe, 1699

Oil on canvas, 35 x 25,5 cm, Stadtmuseum, Berlin

7.

Willem de Rooij, Root XXVI, 2023

Archival pigment print, 35 x 35 cm

8.

Willem de Rooij, Blue to Black, 2012

Industrial wax print on cotton, 550 x 120 cm

Willem de Rooij, Black to Blue, 2016

Indonesian batik technique on cotton, 550 x 120 cm

Installation view: Mindful Circulations, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum, Mumbai, 2019

Photo: BDL Museum

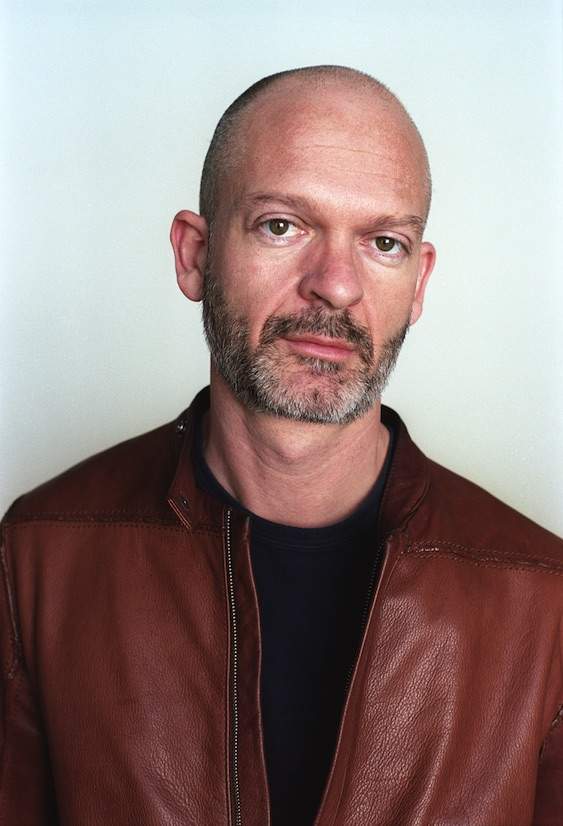

9.

Willem de Rooij,

Photo: Jonas Leihener