Features #4 — February 2022

Yann Sérandour in conversation with Nicolas Vamvouklis

Yann, you mentioned in previous discussions that your work is similar to that of a historian. Is there any specific type of stories you are currently interested in?

Linking fortuitous events or objects found by chance and giving them meaning, or at least drawing a line that would lead us from one to another: this is what drives me in my work. The dispersion of sources across time, space, and contexts captivates me. My focus on historical sources is directly related to their inevitable distortion and I am interested in tracking the more or less sinuous trajectory of their retransmission.

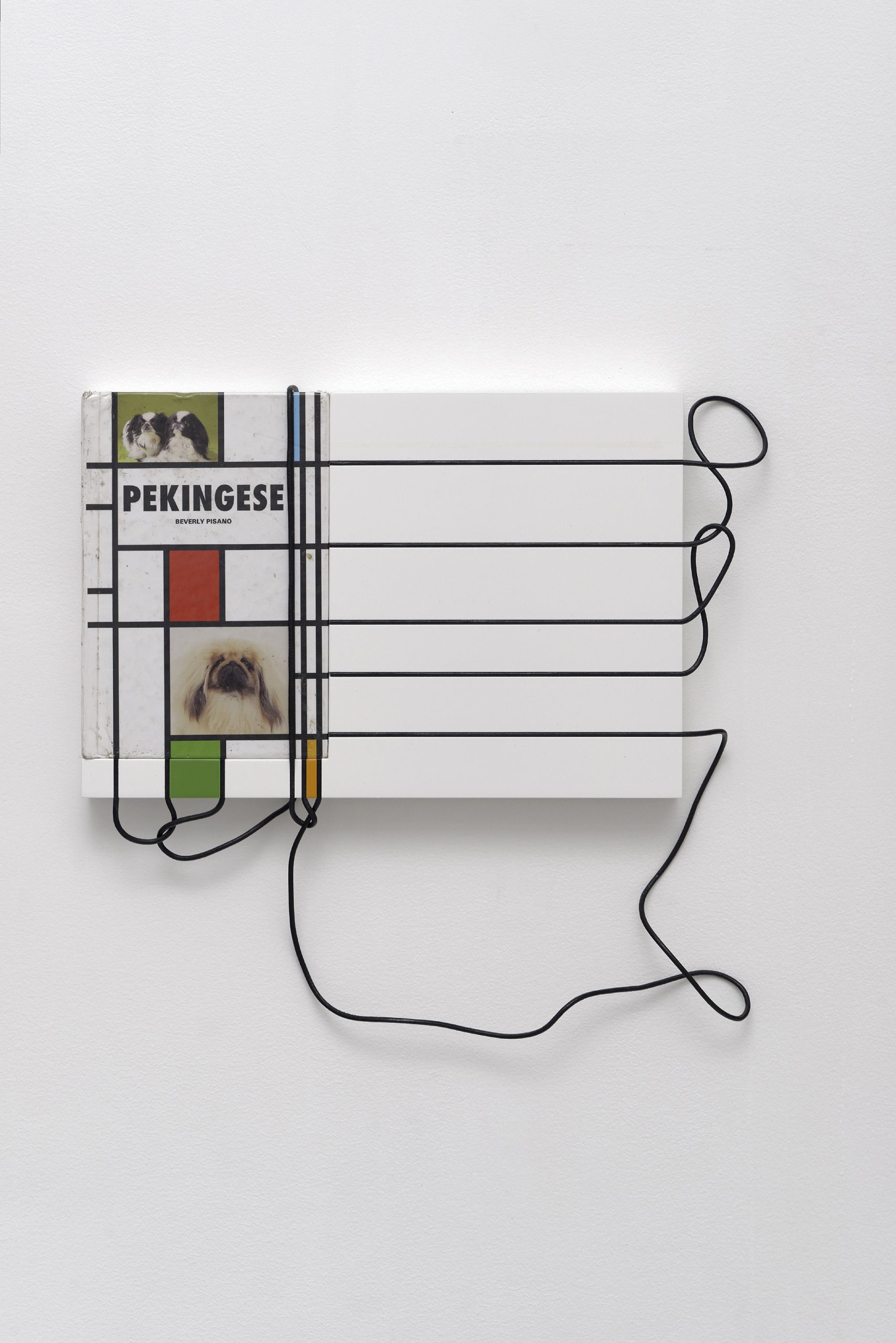

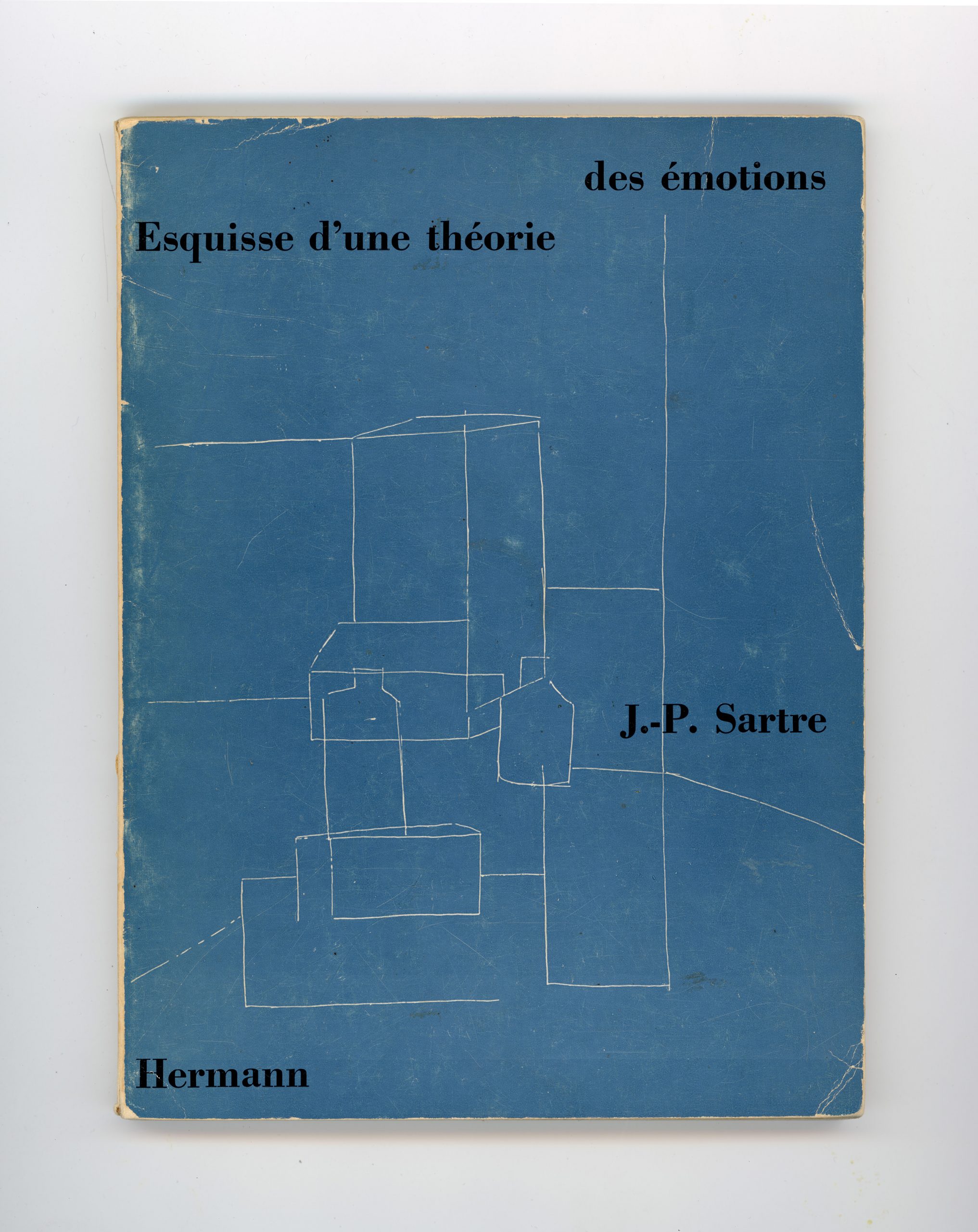

A few weeks ago, I came across a small book by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre: “Esquisse d’une théorie des émotions” (Sketch for a Theory of the Emotions), republished by Éditions Hermann in 1960. Its monochrome blue cover was composed by Swiss typographer Adrian Frutiger and illustrated by Geneviève Asse, a French painter whose silent and meditative work touched me a lot when I was a teenager and to which I strangely returned during the pandemic. I started collecting all the copies I could find to contemplate the shades of blue of their covers, more or less faded by time and use, but also according to the successive printings between 1960 and 1995.

I don’t know yet where this will lead me, but I like to let myself be guided by this kind of findings that always trigger unexpected research and encounters.

You often appropriate art produced by figures historically associated with the tradition of Conceptual Art. Who are your artistic icons from the sixties and seventies?

Ed Ruscha is an artist who has left a deep impression on me.

First of all, for his work on language and its figuration, but also for the suspended atmosphere of his paintings and the numerous vacant spaces in his artworks and artist’s books. So many breaths. His work is at the same time, hot and cool, humorous and contemplative, clinical and sensual. I love its thermostatic nature that takes us from freezer to fire and back again.

Lawrence Weiner, who recently passed away, was also my hero. The space his work leaves for the receiver was a breach through which my work could be built. These hospitable works are different from the sometimes dogmatic and authoritarian approaches of other conceptual artists of the same period. They also have a strong link with graphic design, to which I am very sensitive.

In a completely different genre, the spiritual lightness of Robert Filliou and the archeological delirium of Raymond Hains have also affected me. It is not really a question of appropriation. These works called me, and I wanted to answer to them as one would answer a phone call. They are part of my personal trajectory. I don’t think I expropriated the sources by drinking their water.

Let’s talk about your fascination with cacti. I am also a big fan of them, and as you already know, your work “Cactus Show & Sale” has been on my Facebook cover since 2015.

I don’t remember how this story started, but it has been with me for a long time. This fascination for cacti, or more precisely my interest in their cultivation and domestication, is a form of identification with this very frugal plant, capable of surviving in the most hostile environments. It also tells the story of the evolution of our relationship with living things, between the desire for control and care, domestication and affection. In the case of the cactus, its hostile environment is not the desert, which contributes to its fertilisation, but the domestic and exhibition spaces where it is acclimatised. In these artificial conditions, its survival depends on the care it receives, but it is incredibly resistant. The simple, sculptural forms of cacti fascinate me. Their growth is sometimes very slow. These plants are enigmas.

I am trying to imagine your studio and I am pretty sure there are old books and magazines everywhere. How does your working space actually look like?

I don’t have a studio as such. Depending on the phases of work and idle time, I move around several rooms between conception and reverie. My workplace is a kind of deviant waiting room. It is located in a former doctor’s office, where I broke down the interior walls. The separation between the office and the waiting room no longer exists. There are stacks of all kinds waiting to be read or integrated into future work. My library is two floors up, under the rooftop. I store my books and archives there as one would store grain. It is a place of memory and resource. In the adjoining apartment, where I live with my family, old books sit alongside the latest fashionable publications. They are shelved in a sculpture by my friend Ben Kinmont, who is an artist and antiquarian bookseller (and also an avid surfer). During the pandemic, I stopped making art and focused on reading, waiting, and contemplating. I practice fallowing; I try to measure how far it is possible to do nothing and when it becomes necessary to make something. Trying to do as little as possible is a real art and a life lesson, isn’t it?

I couldn’t agree more! The design of your website is fascinating, full of emojis and enigmatic links. What is your relationship with the digital reality? How about social media?

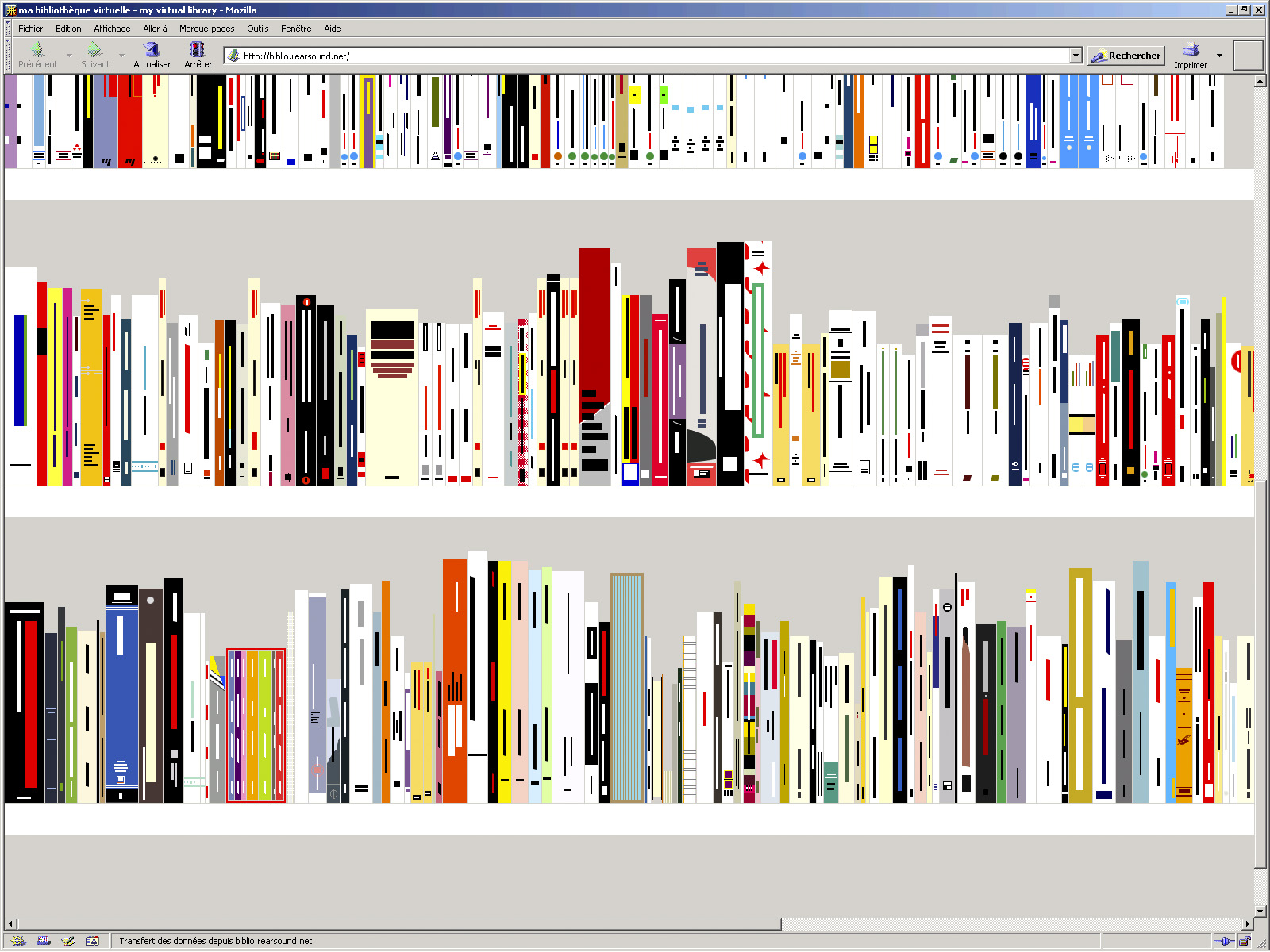

Digital reproduction has been an important part of my work since the beginning. It testifies to this migration of sources from one world to another, how they are absorbed, digested, degraded, and paradoxically find another vitality linked to their extreme circulation. One of my first works (“LOW”, 2003) was made from a pixelated detail of a reproduction of a painting by Ruscha found on the Internet: “The Back of Hollywood.” In the early 2000s, I started drawing gif icons of book spines from my library that I published on the web. This web page is still online twenty years later. These early works may have a different resonance today because of the time we spend living vicariously through screens. What kind of emotions are we capable of? These links that make us slide from one image to another… What do they say? What experiences do they provide? I am torn between a certain taste for surface effects, furtive appearances, and the tracking of sources. All these things are closely related to our digital reality, but also with ancestral techniques of trap hunting or even collection.

Could you share with me your new projects? Is there any show coming up in the near future

Today, the notion of the project seems to be more and more inadequate. I would like to escape from it. I try to live according to the weather, paying more attention to the things, situations, and people I live with or come across on occasion. Welcoming what comes without warning and enjoying the pleasure of being available is what delights me the most. Signs of overactivity are, for me, real nonsense. They alter the capacity to listen and receive. The most accurate works I have been able to make are those I do as little as possible and which were, in fact, already there, waiting to be discovered. This is perhaps akin to a collector’s activity. I see the exhibition as an opportunity for a series of accidents. And when everything lines up effortlessly, with a certain fluidity and grace, the moment is right! Maybe it is about becoming a cactus? Would you seriously consider showing a live cactus in the near future? Or would you rather receive an emoji on your smartphone?