Eteri Chkadua in conversation with Elisa Carollo

Throughout your career you have been able to willfully and wittingly interweave personal narrations with socio-political commentary of the events around you, as well as back in your home country Georgia. From the radical Rasta paintings in the ‘90 to the more directly political and autobiographical ones in the early 2000, you have been showing how the private sphere is inescapably mingled with the political one, as well as how the war is still a domestic and daily experience, for many. Paintings have long been used to pass on history through generations, including wars. What kind of role and function do you think painting should have in relation with today’s society, and with the increasing geopolitical instability we are experiencing?

In my opinion, the most interesting paintings in history describe their time: Art has the power to engage with current events and develop societies. If more artists would address today’s political instabilities, I feel this would have a strong effect in changing their perspectives of “wanna be dictators”. I also understand the fear involved in doing so, especially in some countries. I grew up in the Soviet Union, but Soviet era paintings were so boring to me: artists were never expressing their positions against the dictatorship, out of fear of execution and punishment. In fact, most of the painters in my town Tbilisi became rich painting portraits of Soviet dictators, commissioned from Russian institutions. In contrast, my Georgian professors of painting did not want us to learn realistic styles associated with the Russian School of Social Realism, and they directed us instead to practice impressionism and abstract painting styles. I was one of the very first Georgians who was able to arrive in the US 1988, at the time of the very beginning of the breakdown of the Soviet Empire. To my big surprise most people I met in the US those days, had never heard of the existence of my country: I used to have long conversations explaining that Georgians were not Russians, that we had our own, unique language and traditions. Naturally, I became a “representative” for my country, but in order to make my messages visually clear and understandable for both Georgians and foreigners, I decided to teach myself to use a realistic painting style – definitely not the most appreciated one at the time of Conceptual and Minimalist art. After a whole day painting, at night I would go dancing and listening Hip hop and Reggae music at nightclubs. Meanwhile, Russian troops started annexing Georgia’s territories, including villages and towns of my closest relatives on Black Sea coast and anarchy and a civil war engulfed Georgia. I was getting phone calls from my brother, telling me horror stories about what was happening in my country. I had to emigrate my immediate family members to the US and helped relatives–refugees who ran away from the war zone . The political situation in my native country and my personal life were always inevitably entwined in my mindscape, and this reflected in my paintings.

Usually, when I start a painting, I make a few drawings where I drop off my emotions experienced at the time: as first thing, I create a facial expression of a character who is expressing those thoughts and emotions and then create the backgrounds and add details to make the viewer experience the situation I am describing visually.

I don’t know how others feel when creating their art, but in my case, I feel the need to share my country’s story, and I want to take the viewers experiencing on every side to feel the situation. I strongly believe art has the power to change societies, both in the short and long run. I hope many artists these days would address the political instabilities we face today.

Getting into the paintings on view, they are part of a body of work you made to specifically address the threat of Russian invasion in your home country, Georgia and the war that followed. Something that still has ongoing consequences today in the country’s politics. Can you tell us more about the genesis of these paintings, and the stories behind?

I created 9 paintings about Russian geopolitical ambitions. The 2 paintings on view are telling stories about 2 different wars. After the breakdown of the Soviet Union, Russian troops annexed Abkhazia, Georgian territory on the Black Sea coast, after the Kremlin provoked war between Georgians and the Abkhaz ethnic group.

Abkhazia, (in Western Georgia originally was land of the Ancient Georgian kingdom called Colchis, home of Medea and destination of Argonauts– according to Greek mythology), was populated with Greeks, Gypsies, Armenians, Turks, Russians, Tatars, Abkhaz and Georgians living together for centuries in peace, frequently intermarried, celebrated social events together, buried dead relatives together and toasted each other’s health. Nobody would have imagined that one day, the little subtropical paradise Abkhazia would be engulfed in a brutal war between Georgians and Abkhaz people. One of the paintings displayed in this show is titled ICE CREAM: I was affected by the story of a person who was present when shooting went on for hours in the streets of the town Sukhumi (Abkhazia). A man riding a bicycle and selling ice cream from a box attached to his bike, entered the road. Confused and frightened by gunshots, he froze, unable to move. For a moment the shooting stopped. From both sides, fighters dropped guns, came out and bought ice cream. They returned to their hiding places and a few minutes later, when they finished eating ice cream, the shooting continued.

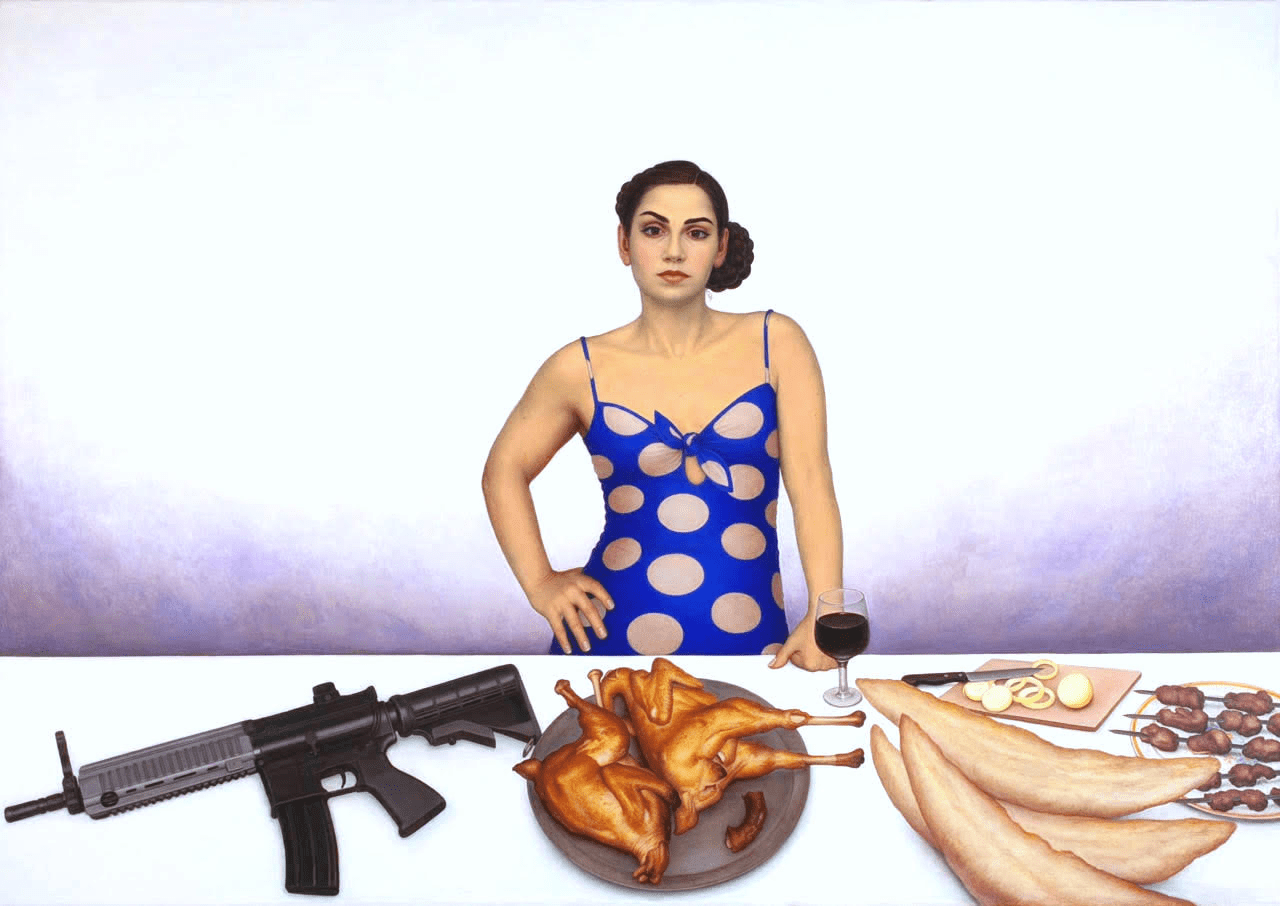

Another painting on view “IN BLACK” is dedicated to the soldiers who fought defending their homeland in a 5 day war in the Caucasus mountain region, between Georgia and Russia, 2008.I wanted to express myself through that woman in the painting, depicted while preparing for the traditional ceremony called Ormotsi. Her eyes cannot resist going over the Newspaper’s headline, thinking: “What exactly does Russia want anyway?”. The article she’s reading states: “Unfortunately, despite the call of the international community, the Russian Federation continues its violation of international law principles and obligations assumed under the ceasefire agreement. Since occupational forces in the village of Ditsi in the Gori district, resumed installing barbed-wire fences”. It’s 3 pm. Guests will be arriving in a few hours. It’s time to set up for the Supra (the dinner Table). Time to get dressed. She looks in the closet, gazes at the red Polka dots dress she so badly desires to wear. But she puts on the black dress instead. On the 40th day after the death of a loved one, in Georgia, as all across the Caucasus region, a big dinner ceremony called Ormotsi (40) is held to mark the end of the period of mourning — only after then, close relatives of the deceased may take off the black dress; Stricter keepers of tradition will keep the black clothing on for exactly a year.

I made a few other paintings on the Russian invasion of Georgia, as was close to my family.. I woke up one morning in Montreal, had a dream: my (years ago dead) mother was telling me that she was freezing. The same day I got a call from my brother from Georgia that my mothers 2 aunts froze to death while crossing the mountain, while escaping the war zone in their home town Sukhumi, where kremlin provoked the war between Georgians and Abkhaz ethnic groups that ended with Russian troops occupied the land and 300000 refugees leaving their homes This story always crosses my mind ..

Black Sea

Sniper

Tamada

Oto baya

In Black

Ganda Bherundasana ( The Terrible Bird)

As you said, the situation is still quite critical in Georgia, with Russia’s interference in recent political turns, and the threat to get soon into a similar situation as Ukraine, if the current president refuses to be that condescending. As the international media are reporting little if not nothing about the country’s situation, can you walk us through the recent events?

Russia occupies 20% of Georgian territories. The current Georgian government has been installed and controlled by the Georgian Oligarch “Made in Russia” in 90s. The government members spreading the fear among people that if Georgia sides Western World against Russia, it would face another war with Russia and embarrassingly, are not clearly stating solidarity with Ukraine. But the citizens in Georgia have been staging numerous demonstrations to show Ukrainians their solidarity. TV channels are reporting nonstop on the current situation and expressing their opinions boldly.

We believe that Ukrainians are fighting everybody’s war against dictatorship and colonization still existing in modern history; Ukraines winning over Russia will be the final defeat of remnants of the Soviet Union. Winning this war could also likely free Georgian occupied territories annexed since the 90s. Meanwhile the Georgian government keps is jail Georgia’s 3rd president Michael Saakashvili, despite many demonstrations Georgian citizens are asking for immediate release of Saakashvili.

He was arrested on October 1st, 2021 upon his arrival to his home in Tbilisi, on politically motivated charges. Since then, it has been reported he was poisoned in jail with heavy metals, including Mercury and Arsenic, and is denied fundamental rights guaranteed under international humanitarian law.

International media are reporting very little on what is going on in the ec-Soviet regions. Even with Ukraine, they reported only after the invasion, so when it was clear that a war was starting, despite the Ukraine-Russia crisis having actually escalated over the years. From your personal experience, how do you think this has changed, now that social media allows common people to report first hand what’s going on? What do you believe can be the role of art, especially in raising awareness about events the media are not really covering enough?

I have a few European and American friends, journalists and war photographers who have covered wars. I describe them as heroes, as they had put themselves in danger of reporting from the immediate war zones. No parents want their children to die in other countries’ wars. However, not reacting timely to the dictators, in the long run, causes larger destruction- that’s what happened to Ukraine.

A small country like Georgia, unless it’s in a war, hardly gets attention in the media. The 5 day war in 2008 between Russia and Georgia had limited international media coverage. Some political analysts commented that, it this war was given more attention, the war in Crimea in 2014 and the current war in Ukraine could have been avoided. * ( There are 2 very interesting analytical books written about it: “A Little War That Shook The World ” and “The Guns of August 2008” . But most people haven’t even heard of this war and hardly would be interested in reading details and analyses of it…).

People in peaceful countries who work hard and get home tired, don’t want to stress about other countries’ troubles. Social media definitely has been effective in reaching info to general audiences.. Personally, I can’t avoid listening to Georgian media almost every day. I definitely see my paintings role in bringing other then Georgian people’s attention to my country:

In my creating process, before starting the painting, I make a few drawings, where I “drop off” my emotions and thoughts I experience at a time. I work long on creating a facial expression of a character who resembles me and is going through those emotions — I want to make sure that facial expression and body language will “communicate” to the viewer. I create backgrounds and details that in my mind would make the viewer experience those feelings emerging from the situation I am describing in the themes of paintings.

In the most recent body of work you have been working on, you made a sort of negative version of some of your previous works: you are still including yourself, but this time as reporting or commenting from some alien space, which creates an enigmatic suspension of disbelief, and make the narrative more dramatic. In one in particular, you imagined yourself writing a letter to the current Georgia’s president. What would you imagine to say in this letter? How does this new series of works still address and tackle the threat of Russia violations and interferences for ex Soviet countries?

I work and live in different countries. My Georgian friends joke that I am always on a “another planet”, especially in bringing up certain arguments or issues that haven’t been addressed there yet, or sometimes challenging centuries old Georgian traditions. Some years ago I made an exhibition there to start conversation for legalization of LGBT rights and started conversation for legalizing marihuana, as numerous people were getting arrested for its use. In my recent paintings I created a character, “Blue Nomad”, and started sending messages from “another planet”.

In one of those paintings “Letter To The President”, Blue Nomad writes to the current Georgian president to ask to release from jail Georgian journalist Nika Gvaramia and above mentioned 3rd president Michail Saakashvili, to warn the government that the destruction of these 2 extremely bold individuals will be considered an enormous mistake in the history and will only serve as a perfect gift to the Kremlin’s ambitions. I’d like to believe that my “new colors” and an image of my “alien nomad” will have a long visual imprint on the minds and will bring to the attention for a new generation of viewers to continue the fight in the right direction.